Research Article

Research Article

Diabetes of Type 2 and Patients: A Point of View on the Making of The “Patient Work”

Houinsou Dedehouanou*

Retired Professor from the Faculty of Agricultural Sciences, University of Abomey-Calavi, Benin

Houinsou Dedehouanou,Retired Professor from the Faculty of Agricultural Sciences, University of Abomey-Calavi, 01BP 526 Cotonou, Benin.

Received Date: October 10, 2022; Published Date: November 21, 2022

Abstract

How is the “patient work” outside medical and hospital environment performed in case of diabetes? This is a recurrent question to all patients who survive comatose crisis. We consider a combination of continuous medical efforts and lasting “patient work”. The present case report describes daily glycaemia tests and walk in footsteps over six hundred eighty-eight (688) days. It addresses the relationships between both variables, keeping dietary conditions stable. The results provide evidence of a significant and positive relationship. However, the cost side of the “patient work” is rather high and discriminates against patients with low purchasing power. The cost constraint strikes attention to the public health policy in the African context.

Keywords:Diabetes; Patient work; Daily blood tests; Daily walk; Positive relationship; Cost constraint

Introduction

Diabetes of type 2 is one of the deadliest chronic diseases in Africa. The rational is that carrying out medical, dietary and physical activities is not easily at the reach of all health actors [1]. Hopefully, there is the medical division of labor which stresses selfmonitoring as part of the healing process. The question is whether such a medical division of labor is neutral, or is it entangled in social power relations? In fact, such a responsibility which calls for selfconsciousness says nothing about the phenomena of surveillance and disciplinarization that meet with varying degrees of resistance and rejection on the part of potential patients. It does say nothing about the level of cognition needed to process information on the illness. One obstacle is how to monitor a survey toward recording data on glycaemia: conducting blood glucose tests and keeping a blood glucose diary, sticking to appropriate health and dietary practices (nutritional balance), physical activities and others. One other obstacle is the understanding of the work on the data collected, which mainly consists in interpreting those data in relation to oneself context and linking them with other forms of knowledge, work that is also characterized by its “emotional” dimension for the patient (anxiety, fears, affective attitude to the data, etc.).

A tester and consumables are needed for the blood glucose levels and they are costly. Blood glucose diary is hardly at the reach of common people. Health practices entail medication and assiduity of purchasing drugs and the like. Dietary is one fundamental dimension of nutritional balance which contributes to the healing of patients. In African context and maybe elsewhere, there is an issue with respect to food [2]. There is a saying that when someone is fat, people ask rather “where does he/she get the food?” than “what is it about his/her diet?” In such a context the common opinion is unfavorable to the management of diet.

Physical activities, on the contrary, seem more accessible to most people, although heat is much less encouraging for it.

This paper seeks to call attention of patients on “patient work” during the healing process of Diabetes of type 2, and on the implications in terms of cognition, initiatives, and attentions with respect to physical activities.

Our analysis is more focused on physical activities than nutritional balance (dietary). We internalize the proposition of intense cognition in the planning process of physical activity. We then assume initiatives of physical activities on daily basis and attentions over days, months and even years. Our contribution is to draw on models in the social sciences in our analysis, by linking glycaemia (level of glucose in the blood) and physical activities. We thus propose to explore the “patient work” (physical activities as part of it), which we consider to be a fundamental dimension of “patient work” as defined by the World Health Organization (WHO).

Case Presentation

Methodology

Materials: We refer here to the toolkit in use for the “patient work”. The first important tool is a tester, the one needed for measuring glycaemia, i.e., the level of glucose in the blood, on a daily basis. It is of interest to state that the cost of measuring glycaemia three times per day or/and only once a day in the morning at the wake is very high. The second one is the daily diet, which should be balanced. We claim a nutritional balance through a daily diet recommended by the nutritional expert who is a physician and following a one-week diary. For that purpose, it is continuously applied over the period of 688 days and even more. It is important to admit that the diet is very expensive and cannot be afforded by anyone without adequate purchasing power. The third important tool is to achieve physical activities. Recall that WHO celebrates ten thousand (10 000) footsteps walk a day in order to keep pace with a healthy and rewarding life. The fourth tool to be considered is “taking medication either orally or –in the case of insulin– by injection”. We stress the oral daily medication which is costly as well. Overall, tools are hardly at the reach of all patients.

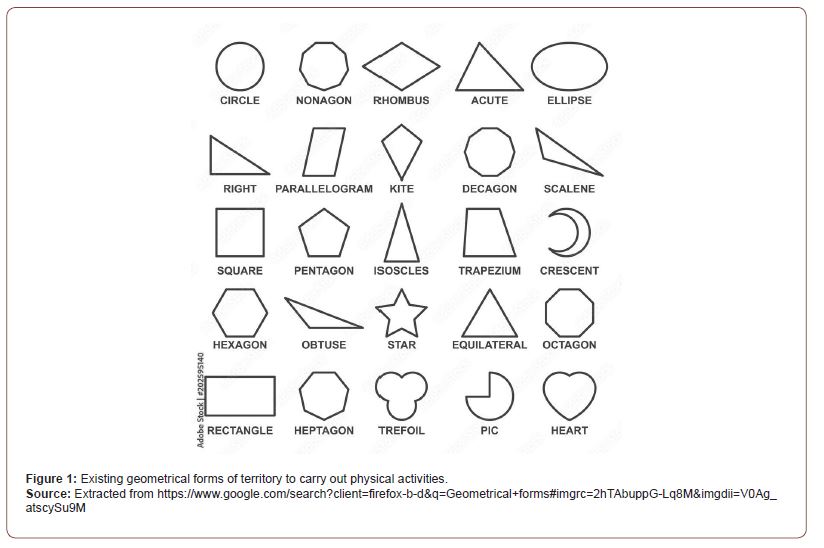

In order to correlate the measures of glycaemia and walking as acknowledged by the WHO, there should be measures of the number of footsteps. However, each individual may achieve it through various ways: step by step indoor device, indoor and outdoor walk. On the outdoor side, there is a common linear walk. Each way demands the calibration and scaling of footsteps. The question is how many footsteps are needed to walk along a geometrical form of a territory (cf. figure1: geometrical forms). This should be settled from the outset.

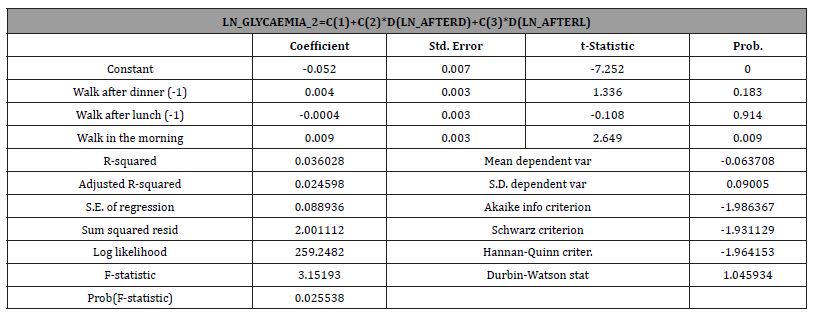

Table: 1Modeling Glycaemia.

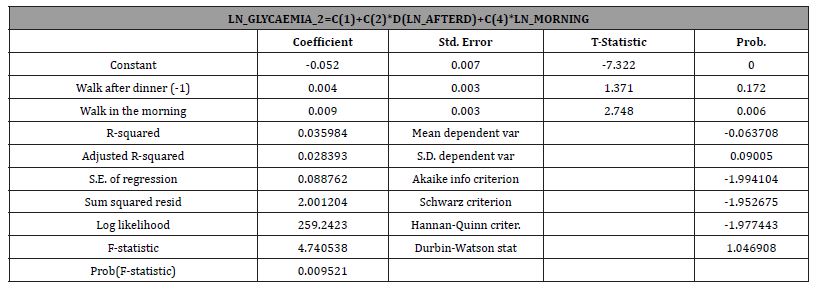

Table: 2Modeling Glycaemia.

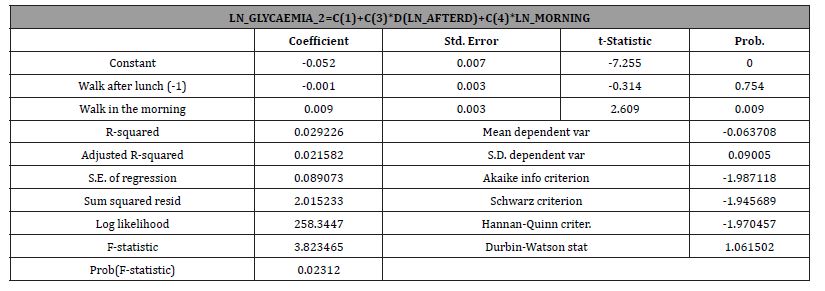

Table: 3Modeling Glycaemia.

Methods of analysis

Walking during three different times is assumed to influence glycaemia (level of glucose in the blood) and this in terms of the number of footsteps:

i) First walk (ratio): the lag value of the number of steps recorded over ten thousand after lunch time the day before the measure of glucose level (AFTERL);

ii) Second walk (ratio): the lag value of the number of steps recorded over ten thousand after diner in the evening before the measure of glucose level (AFTERD);

iii) Third walk (ratio): the value of the number of steps recorded over ten thousand early in the morning just before the measure of glucose level (MORNIN).

iv) Total walk per day: First walk + Second walk + Third walk

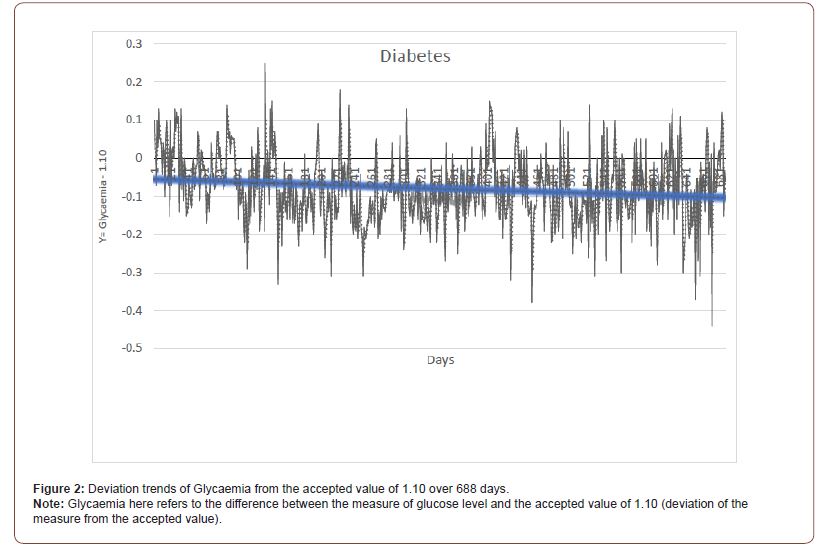

Glycaemia (level of glucose in the blood): measure of glucose level – 1.10 (deviation of the measure from the accepted value “1.10”). This is to say that deviation is positive when the level of glucose in the blood is high and negative otherwise.

Walking in the morning just before a test of the level of glucose in the blood is questionable. Doctors advocate a test early in the morning at the wake. Patients in their own right can explore various ways to reduce the level in case of hyperglycaemia.

Having collected data on the two variables, the next step is to explore various functional forms. We then apply the neperian log function and the mathematical form of the model is:

LN_GLYCAEMIA_2=C(1) +C(2)*D(LN_AFTERD)+C(3)*D(LN_ AFTERL+C(4)*LN_MORNIN (1)

Results

We explore the descriptive characteristics of the two variables on the one side, and the relationships between those variables on the other side.

Daily glycaemia (level of glucose in the blood – 1.10)

It is of interest to claim that daily Glycaemia (level of glucose in the blood) is very much contained around the accepted value of 1.10 over six hundred eighty-eight (688) days. The deviations are clearly contained within the range of -0.44 to +0.25. The trend line is declining with the highest point under 0.00, stating that in general the levels of glucose in the blood are below the accepted value. This result is very encouraging as an achievement of “patient work”.

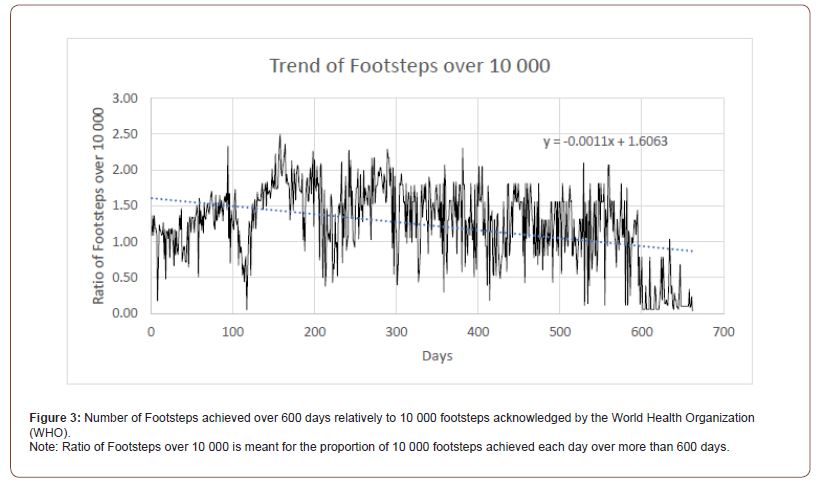

Daily walk records

The recorded daily walk-in terms of footsteps play a great deal of influence on glycaemia. These footsteps play other physiological functions on the human body as acknowledged by the WHO. For instance, rapid or speedy steps influence “blood pressure”. They importantly contribute to burning excess glucose in the blood, eg. While glycaemia patient walks the level of glucose in the blood declines over time. The walk ratios are over 1 in the first year and beyond but walk declines to hundreds of footsteps after six hundred (600) days. It is of interest to claim that the number of Footsteps achieved daily over 550 days is greater than ten thousand (10 000) footsteps. But, after 550 days of a highly valuable “Patient work” the ratio falls below the standard of the WHO. The multiplier of the daily achievement is contained within the range of +0.10 to +2.50. The trend line is declining with the highest point at 1.70 (17 000 footsteps), stating that in general the number of footsteps achieved daily is greater than ten thousand. On the contrary, and due to a better management of “Patient work”, achieving much less footsteps than ten thousand (10 000) has little impact on the change of levels of glucose in the blood. This result is also very encouraging as an achievement of “patient work”.

Is the WHO right by acknowledging ten thousand footsteps per day?

It is clear that WHO’s acknowledgement of ten thousand (10 000) footsteps is beneficial to health as a whole. But is it right particularly to diabetes’ patients?

We explore the relationships between glycaemia and walk at three different times as explained in the “Methods of analysis” above.

The running of the econometric model expounded earlier provides evidence of the following relationships:

The three models containing three alternative combinations of timely walk are all significant at 1%. However, only the Walk in the morning is significant at 1% for the three models (cf. tables 1, 2 and 3). In addition, on the sign side of the coefficients walking in the morning significantly reduces glycaemia while walking at lunch increases it.

Discussion

The apparent contradiction between the trend of the deviations of Glycaemia and that of the ratios of 10 000 footsteps achieved over more than six hundred (600) days derives from physiological as well as mental adjustments of a patient. The fact that much fewer physical activities do not impede the trend of the deviations of Glycaemia explains easily the adaptation process undergone by the patient’s physiology. As claimed by Guérin & Zeitler [3] and Schlegel [4], a better dietary and a better management of physical activities evolve from re-appropriation, transformations of social interactions.

One cannot acknowledge the management of life with the illness to the work dimension alone [1]. It is of interest to enrich the “patient work” with sociological perspective by highlighting the relationships between the use of blood glucose self-monitoring devices and changes in “patient work” and in subjective perceptions associated with the body and the manifestations of diabetes. Patient work can be visible or invisible.

Dietary concerns play a very great part in the “patient work”. According to Mathieu-Fritz and Guillot [1], these require the acquisition of knowledge and expertise on the illness, in other words on its physiological effects and their treatment, together with the implementation of different drugs. However, dietary is not just a means to achieve the “patient work” it is communities’ cultural identity as soon as it entails the environmental, economic, social, and cultural spheres [5]. Assuming the inverse leads irremediably to what Paxton, Pillai, Phelan, Cevette, bah et al. [6] identify as “dietary acculturation”.

The costs of the whole glycaemia healing process are to be considered here a great constraint to the “patient work” [2]. Mathieu-Fritz and Guillot [1] stress the cost side in general and that of the device or the tester in particular. The cost side of the “patient work” is not socially affordable to a common patient [2].

Subjectivity always appears when we need to write and talk about ourselves. As Dutoit [7] demonstrates, the “work on oneself and relative to oneself” is perfectible. This is to assert that all ethnographic conditions are hardly met to deliver the present paper. However, the understanding of the “patient work” for diabetes’ illness occurs over time [8]. Learning process and its trajectory are key artifacts of the “patient work” [4,910].

Concluding Comments and Implications to Patients

Management of the “patient work” is at stake in the present paper. For that purpose, we set several indicators of which glycaemia, number of footsteps (walk), blood pressure, dietary monitoring and so on. Satisfaction of most physicians is a very important reward for the patient. In order to play a role in others’ healing process, we suggest paying attention to the activities as follows:

Three walks and three tests of the level of glucose in the blood are carried out per day (early in the morning at the wake, at lunch time, and at the evening after dinner). Hopefully, more than one year later doctors recommend to the patient to leave the mentality of illness by reducing the number of tests to one, and later spacing days for the tests.

The “patient work” can be very much adjusted over time. For instance, skipping dinner is a good alternative. There is a concern around walking three times a day as it is constraining for patients who are busy with professional activities. From the results above, walking early in the morning just before taking the level of glucose in the blood (glycaemia) is partly a good physical activity.

There is a real concern about the costs of the “patient work”, the latter also appears time consuming. Each patient must contextualize it following his/her own personal experience of the existing social conditions.

Acknowledgement

We thank doctors of the public hospital from the “Endocrinology and Diabetes” service at “Porto-Novo” in the Republic of Benin. We thank our children and their mother for their care during such a difficult time. We strongly certify that the opinions expressed in the paper are our own.

Conflict of Interest

Declare if any financial interest or any conflict of interest exists.

References

- Mathieu Fritz, AC Guillot (2017) Diabetes self-monitoring devices and transformations in “patient work”. Journal of Anthropology of Knowledge [Online] pp. 11-4

- Salemi O (2010) Dietary practices of diabetics. Study of some cases in Oran (Algeria). Rural economy pp. 318-319.

- Guérin J, A Zeitler (2017) Life course learning and transformations of life habits of a diabetic patient. Education and socialization pp. 44.

- Schlegel V (2022) Constrained autonomy. The social uses of blood glucose self-monitoring by people with diabetes. Anthropology & Health, Articles in pre-publication.

- Herrscher E, M Poulmarc’h, G Palumbi, S Paz, E Rova, et al. (2021) Dietary practices, cultural and social identity in the Early Bronze Age southern Caucasus. Paléorient pp:47-1.

- Paxton A, A Pillai, KPQ Phelan, N Cevette, F Bah, S Akabas (2016) Dietary acculturation of recent immigrants from West Africa to New York City. Face à face pp. 13.

- Dutoit M (2017) Work on oneself and about oneself on the occasion of an experience story: summoning different spaces of activity. Education and socialization pp. 44.

- Crozet C, JF d Ivernois (2010) Learning the perception of fine symptoms by diabetic patients: useful skill for the management of their disease. Research & Education 3: 197-219.

- Nguyen Vaillant, MF (2010) The diabetes monitoring card. Journal of Anthropology of Knowledge pp. 4-2.

- Piras EM, Miele F (2017) Clinical self-tracking and monitoring technologies: negotiations in the ICT-mediated patient-provider relationship. Health Sociology Review 26(1): 38-53.

-

Houinsou Dedehouanou*. Diabetes of Type 2 and Patients: A Point of View on the Making of The “Patient Work”. Endo & Diab Opn Acc J. 1(1): 2022. EDOAJ.MS.ID.000502.

-

Liver, Hyperglycemia, Insulin-Sulfonylurea, Erectile Dysfunction, Macro- Vascular Disease, Cell Dysfunction, Apoptosis, Autoimmune Destruction, Insulin, Immunoglobulins

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.