Research Article

Research Article

Increasing Sexual Self-Efficacy Among College Students Through Telehealth Consultation: A Case Management Approach

Pamela Stokes, MHA, DNP, RN*

University Health Services, Oklahoma state University, USA

Pamela Stokes, Department of Health science, Oklahoma state University, USA.

Received Date: October 01, 2020; Published Date: October 20, 2020

Abstract

Unsafe sex is one of the main risk factors for young people, ages 18 to 24, in contracting sexually transmitted infections (STIs) [1]. Recently, the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) stated that nearly half (46.8%) of young adults surveyed across 42 states, had engaged in sexual intercourse and were currently sexually active [1]. This paper summarizes the role that case management, using telehealth, can play on increasing sexual communication self-efficacy, ultimately reducing STIs on campus.

After testing positive for an STI (N=11), the implementation of a telehealth appointment with a nurse took place in conjunction with the administration of the Sexual Communication Self-Efficacy Scale (SCSES), before and after the sexual health education. The outcomes revealed that young adults, ages 18 to 24, already possess a high level of sexual self-efficacy, although they lack knowledge of their personal risk for contracting STIs. Furthermore, themes gathered during the telehealth appointment, including

• The desire for easy access.

• The need for support from a trusted health care provider, validates the desire of this population to pursue sexual health appointments and STI checks if a telehealth platform is available.

Keywords: Telehealth; Sexually transmitted infections (STIs); Case management; Self-efficacy; Young adults; Health promotion

Introduction

National College Health Assessment data reveals that on a Midwestern University campus in 2019, only 26.3% utilize protection most of the time or always in comparison to Healthy Campus 2020 national goal of 56.1%, [2]. One approach to prevent STIs in the young adult population is to develop a sexual health education program where individuals have a high level of interaction and rapport with health care providers [3]. Tailoring sexual self-efficacy communication training with preventative mindfulness interventions leads to a positive effect on the intention to discuss safe sex practices with their partner [4].

Self-efficacy is beliefs about one’s ability to engage in a desired behavior or achieve a level of performance [5]. This principle is a key factor in young adult sexual communication and is often associated with sexual health research because the concept drives motivation in avoiding sexual risk behaviors [6]. Sexual communication selfefficacy is associated with more positive condom/barrier attitudes and use as well as managing risky sexual behaviors. The treatment focused office visits that currently only involve discussion surrounding the infection or diagnosis lead one to believe that little is done in regard to empowering young adults to be mindful about prevention. It is critical that the health care providers support young adults in talking to their partner(s) and acting with intention. They are strategic to decreasing STIs. There is a direct correlation in convenient guidance being provided on campus and the probability that one will have sex with protection (or abstain) [8]. Because the number of STIs continues to rise, a need exists to improve the selfefficacy young adults have towards sexual intercourse. This project will explore the role that case management through telehealth can play on increasing sexual communication self-efficacy, ultimately reducing STIs on campus.

Review of Literature

Donne [4] suggest that building rapport and supporting that relationship through case management strategies will be more effective than traditional education approaches to STI prevention. In fact, college students indicated that there is no significance in video, brochure, or other pre-developed material in regard to their motivation to make safe, sexual choices [4]. Interactive teaching, where the student is encouraged to place themselves in another’s shoes, allows them to initiate behavior changes. Lechner [3] validated this statement in their study which found that higher level of interaction with health care providers, patients, and sexual health resources, the better the outcome (meaning no recurrent STIs). Building rapport with providers and having meaningful conversations is more effective with education about safe sex [9].

Historically, self-efficacy and self-management are reflected and theoretically summarized in Pender’s Health Promotion Model [10]. The model explores the factors and relationships contributing to health-promoting behavior and the enhancement of the quality of life. This framework, developed as a guide for processes that motivate individuals to engage in health or healthy behaviors, is appropriate for adolescents and young adults. They have unique health considerations and are in transition as they move from parent-managed health care to personal responsibility for their health behavior choices. They are shaping their life through identity development and processing personal choices and/or newly formed relationships through the evolution of their own perceived self-efficacy.

Similarly, McCutcheon [11] found that cognitive processes, personal attitudes, and social norms affect behavior. Personal actions to sustain or increase wellness have direct correlations to the actions of individuals or groups that assist in guiding individuals towards preventative actions. Nursing has traditionally provided literature that has ignored psychosocial, political, and ethical aspects of health promotion while focusing on patient education rather than health-promoting behaviors related to safe sex practices [11].

Many researchers described successful sexual self-efficacy campaigns through examples from the HIV/AIDS movement. There are several key factors that assisted in the accomplishments of the HIV/AIDS campaign that included:

• Painting a clear, gripping story through media.

• Securing funding for outreach on a large scale.

• Confronting uncomfortable topics.

• Activism/civil disobedience.

• Pushing for patients to become experts [12]. Allowing

HIV/AIDS patients to focus on specific goals, specific institutions, and specific solutions through dialogue allowed them to become empowered and move towards a healthier sexual self-efficacy. In the HIV/AIDS movement example, the patients became experts on both the political and scientific processes that were involved with the disease and assisted in making changes to the overall sexual education approach.

Current models of psychosocial interactions with young adults suggest that there is a limited capacity for clinicians to provide a timely and personalized assessment [13]. Telehealth is a positive alternative that increases access to the provision of evidencedbased care and treatment [13]. [13] performed a pilot study for young adults receiving cancer care and found that telehealth was acceptable for education and psychosocial assessments. There were no significant barriers to the implementation, and over 63% of the participants favored the experience to a traditional face-toface interview [13].

In order to validate health care approaches that facilitate sexual self-efficacy, Van Volkom [14] suggest utilizing methods that provide immediate access and are technologically driven. If health care providers are available for that dialogue, young adults who have frequent discussions about STI prevention, are more likely to make safe sexual choices and communicate more with their partners regarding sexual health behaviors [6]. In fact, encouraging positivity about sexuality may have important implications for sexual health among young adults specifically, increasing the effectiveness of pregnancy and STI prevention.

Quinn Nilas [6] stated that there is limited research available on innovative educational strategies in relation to sexual health, reducing sexual risk taking, and enhancing sexual relationships. A gap in the research exists with what standardized training is in regard to sexual health education, whether throughout public school systems, in higher education, within health care clinics, or in the public health arena. The goal of improving sex education is needed to prevent future STI recurrences. This involves improving communication between the provider and the patient and evaluating sexual self-efficacy of the patient. Therefore, a need exists to examine new strategies promoting STI prevention and communication.

The purpose of this project is to determine the impact on the sexual self-efficacy of college students from their participation in a telehealth case management program on STIs. Aims included: 1) training and implementing effective case management strategies for young adults (ages 18 to 24); 2) providing telehealth case management support for patients that test positive to STI screens; and 3) assessing sexual communication self-efficacy before and after the implementation of the telehealth case management.

Method

Setting and Participants

This project was conducted at a public university located in the Midwestern United States, during the summer and fall of the 2019- 2020 academic school year. Newly diagnosed students (N=11 out of 122), who tested positive for an STI, were invited to participate in this project. The study was approved by the University Institutional Review Board.

Intervention

A Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) model was used when implementing this quality improvement project [15]. The initial improvement goal and the “Plan” component of the model was to increase sexual self-efficacy, thus reducing the number of recurrent STIs. This was done by building rapport and educating students that tested positive for an STI using effective case management studies. The literature search identified the use of narrative storytelling as a teaching method to promote safe sexual choices [1]. Therefore, situational scenarios were discussed at telehealth sessions that allowed the students to put themselves in the shoes of someone who may be at risk for future STIs.

Prior to and after the telehealth case management appointment, data was gathered on the status of the student’s (N=11) sexual self-efficacy communication using the Sexual Communication Self- Efficacy Scale (SCSES). This is the “Do” component of the PDSA model. The SCSE Scale, created and validated by [6], was designed to measure the communication self-efficacy of adolescent men and women. The scale consists of 20 items that measure respondents’ confidence in engaging in a variety of activities with a sexual partner along a 4-point Likert-type scale (1=very difficult, 4=very easy). Permission was granted to utilize the Sexual Communication Self-Efficacy Scale (SCSES) Are you able to put the citation here of the article where you obtained the scale? Results of the scale as well as themes identified from the appointments where are fully analyzed as a part of the “Study” component of the PDSA model.

Data Collection

The students were informed of this quality improvement project by secure message through the student patient portal of the clinic’s electronic medical record when they tested positive for an STI. This was done retrospectively, after their initial face-to-face testing, treatment, and traditional education for a positive result. Participation was voluntary and measures were taken to maintain confidentiality and anonymity. As participants in this project, the students were requested to complete the SCSES which was followed by a telehealth appointment with the Clinical Director (who is an RN) to discuss STI communication and prevention incorporating situational scenarios involving high risk sexual behaviors. Finally, the students were requested to retake the SCSES. The SCSES were accessed through Qualtrics, a University subscribed survey platform, protected by personal password. By accessing and completing the online SCSES, the students were giving consent to be a part of this project. This was also noted in the original message that was sent to each student through the student portal.

The telehealth appointment took place on a web-based telehealth appointment platform, which is HIPAA compliant and password protected. The author contacted each individual to schedule a telehealth appointment and was the only provider performing the case management sessions. Strategies used were taken from the literature and applied to the interactions with the student. They included: 1) building rapport through casual conversation, 2) eliminating a narrowed and defined time frame, 3) utilizing a narrative scenario to allow students to visualize themselves in a high risk situation, and 4) guiding the discussion with pre-determined topics [4].

During the telehealth appointment, the students provided their perspectives on the following pre-determined questions that were developed by the author. The literature indicated that talking with a sexual partner is the most invaluable step in protecting oneself from STIs [6]. The questions included the following:

• Describe the issues you discuss with your partner(s) prior to any sexual contact, if any.

• How would you take steps to protect yourself from an STI?

• What information do you need to feel like you can talk about STIs and safe sex with your partner?

It was stressed to the students that there were no right or wrong answers. The goal was to get them to think about how they approach sexual encounters and empower them to feel comfortable talking about sex. At the end of the visit, a scenario was given surrounding a potential unprotected sexual encounter and the nurse walked the student through the long-term effects of taking sexual risks. After the completion of the telehealth appointment, the patient was encouraged to practice sexual communication with their partner(s) and make safe sexual choices. Then, after a month’s time, a reminder was sent to the patient through the patient portal, with a link to complete the SCSES for the second time.

Analysis

Basic content analysis was performed in two different areas. The first area of analysis was a descriptive statistical summary from the quantitative data gathered from the SCSES pre- andpost- tests. The second area of analysis was a summative content analysis, comparing and noting keywords or themes Hsieh [16] gathered from the three questions posed during the telehealth case management sessions.

Results

A total of 11 students enrolled in the project. All participants who consented to the project were female. The pre SCSES results reflected that participants were comfortable with sexual communication prior to their telehealth appointment. Themes gathered during the appointment validated this statement and additionally, feedback on healthcare access through telehealth, was a key theme.

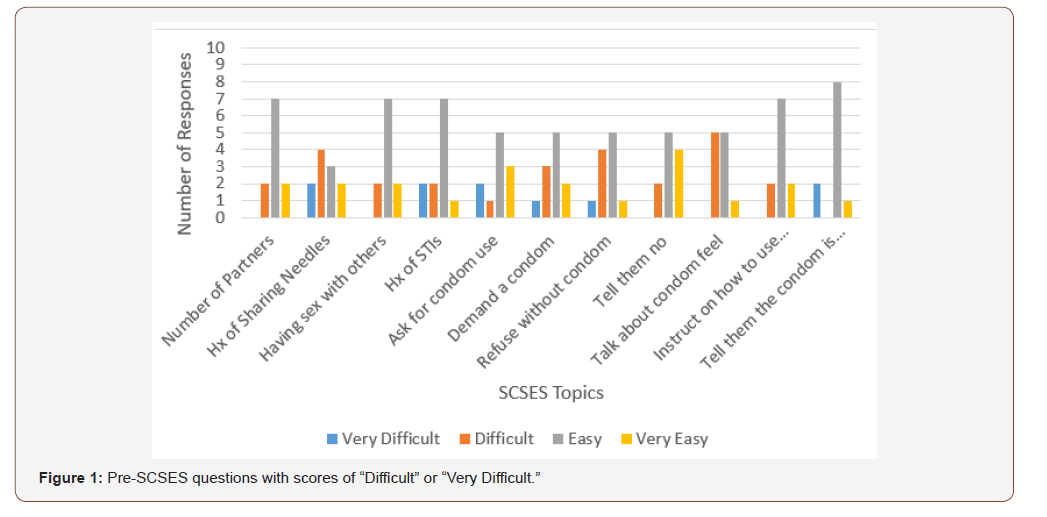

The SCSES itself, had a total of 20 questions that were administered to students. Means suggest that participants were most confident about communicating that a certain sexual activity does not feel good and least confident about asking if their partner had ever shared a needle. Overall, the participants did have an unexpected level of comfort in communication regarding sexuality prior to the telehealth case management. There were 9 questions total that 100% of the students scored as “easy” or “very easy.” The remaining 11 questions revealed that some students had at least a degree of difficulty in talking about the topics with their partner and this is shown in Figure 1.

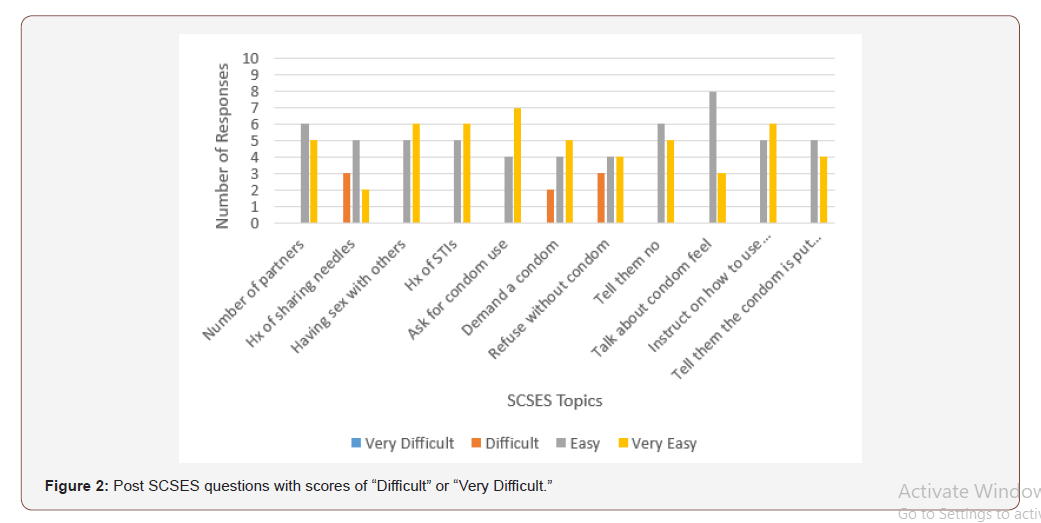

After the telehealth case management was completed, the post SCSES revealed that there was improvement in the student’s sexual communication self-efficacy. There were 8 questions where 100% of the students now had no difficulty in talking with their partner. In some cases, this was over a 20% improvement. Initially, the pre- SCSES responses revealed that 73% of participants found it easy or very easy to ask how many partners someone has had prior to the telehealth case management appointment. After the telehealth appointment, 100% of participants thought it was easy or very easy to ask how many partners someone has had. One hundred percent of participants feel as though it is easy or very easy to tell someone a certain activity does not feel good or feels good, or that they like a certain sexual activity. The post-SCSES results are shown in Figure 2, below.

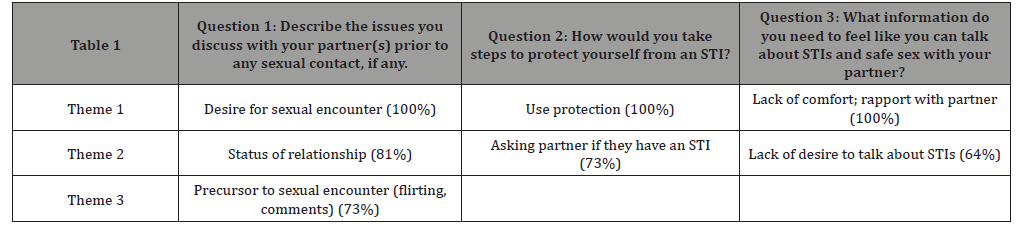

The summative content analysis was performed on questions asked during the telehealth appointments. There were three predeveloped questions that prompted the students to examine their own motivations with sexual communication self-efficacy. Frequency counts of the comments were compiled and reviewed for common themes. The qualitative data from all three questions were independently reviewed and summarized by an expert in content analysis. The findings are summarized in the following section and shown in Table 1.

Table 1:

Question 1: Describe the issues you discuss with your partner(s) prior to any sexual contact, if any. The analysis of Question 1: “Describe the issues you discuss with your partner prior to any sexual content” elicited three common themes:

• A desire to have sexual relations,

• The status of the couple’s relationship.

• The seducing or flirtatious actions or comments that served as a precursor to the sexual encounter.

In the first theme, 100% of the participants reflected that there is a level of communication expressing a desire to be intimate or perform/receive sexual contact with their partner. For example, one participant commented that consent is “important and stressed to us growing up, in school, on social media…. it’s everywhere…so yeah of course we talk about it beforehand.”

A second theme, the status of the couple’s relationship, was identified by 81% of the participants. The participants reflected that they would want to know whether their partner was in a relationship, seeing other people, or serious about them before they engaged in sexual activities. The third theme involved the actions or words that are a part of any flirting that may take place before sex or sex acts. Seventy-three percent of participants identified this as a theme that occurs somewhat naturally. For example, one participant stated that “flirting happens…like certain looks, certain things are said…like the way someone speaks to me, I can tell.”

In summary, participants stated they “felt very comfortable” talking about sex prior to the sexual act occurring. Any form of healthy sexual communication is commonly highlighted as a key factor in influencing positive sexual health behavior, in particularly condom usage [6]. Young adults who do identify an ease with communicating about sex with partners decreases risky sexual behaviors. The communication should surround all aspects of sex, rather than just disease prevention in order for the individuals to maintain healthy sexual behaviors and avoid risk-related sex acts. Thus, the responses indicated that the students in this project do engage in aspects of healthy sexual communication.

Question 2: How would you take steps to protect yourself from an STI?

The analysis of Question 2: “How would you take steps to protect yourself from an STI?” elicited two major themes: 1) use protection, and 2) ensure that their partner was free of infection. In the first theme, 100% of the participants responded with a statement that surrounded prophylactics or protection, like condoms. They unanimously referred to condoms as their chosen protection from STIs. However, 28% of students identified on the SCSES that they had difficulty demanding a condom or barrier be used with every sexual encounter before the case management appointment and 18% still had difficulty with this task after the case management appointment.

The second theme surrounded ways of ensuring that their partner was infection free. Seventy-three percent of participants reported that they made sure through verbal communication that their partner had no infections. This involved asking them if they “had been tested,” talking about previous partners, and asking if their partner had any symptoms that were indicative of an STI like “discharge or pain.” Most individuals who stated they would use a condom also suggested that they would talk about being infection free. [6] states that those individuals who utilize protection routinely are more likely to have positive, stress free sexual encounters than those who do not. Yet, it is common for young adults to avoid directly asking about condom/barrier use and/or STIs [17]. Prior to the case management implementation 18% of individuals had difficulty talking about sexual partners and STIs, yet after the implementation all participants found it “easy” or “very easy” to discuss these topics.

Question 3: What information do you need to feel like you can talk about STIs and safe sex with your partner?

The analysis of question 3: “What information do you need to feel like you can talk about STIs and safe sex with your partner?” elicited two primary themes: 1) a level of comfort with the other individual, and 2) a lack of desire to talk in depth with their partner. The first theme was identified by 64% of the participants. One individual stated that they would only speak to their partner about sex and details surrounding it, “if I was close with that individual or had a relationship. Sometimes sex happens casually without much talking.” Another stated that talking about STIs wasn’t something she did, but she always required condom usage. This is supported in the literature, which describes sexual self-efficacy as being stronger in individuals who are in steady, monogamous relationships [6].

The second theme reflected a lack of desire to talk about sex, STIs, or sexual acts. Twenty-seven percent of participants revealed they did not wish to talk about STIs or sexual details although they were willing to be sexually active. Poor verbal communication between partners is a significant factor is sexual risk taking and common for this population [6].

Discussion

Several things were apparent when comparing participants’ responses in the three questions to the SCSES data. The participants already knew a great deal about sex and STIs and felt quite comfortable not only having sexual relations with others but talking about the aspects of sex they liked/did not like. They did not however, feel comfortable talking about sharing needles and often admitted to engaging in risky sexual taking behaviors without having a close relationship with their partner

In this Midwestern state, there is a great deal of discussion about risk taking behaviors by young adults. In health care, there has been a 283% increase in congenital syphilis since 2014. The resurgence of syphilis cases in recent years highlights the fact that challenges remain in controlling STIs within the state [18]. Additionally, the congenital cases are being properly tracked because of the treatment taking place within the inpatient setting to the newborn. The community rates of young adults being treated are not accurately reflected and statisticians state that STIs often are diagnosed in pairs (or threes). This means that more common infections like Chlamydia and Gonorrhea could be at an all-time high [17].

Young adults engage in cognitive avoidance and are unable to see themselves in a situation that could permanently affect their health [19]. Additionally, sex and sexual acts was reported as part of routine activity for the participants involved in the project. Providers are often focused on curative aspects of care rather than education and prevention [20], thus students are unable to place themselves situationally into examples or narrative scenarios where they would know how to respond to protect themselves [4].

An unexpected theme arose during discussion over the three telehealth questions. Participants overwhelmingly inquired about the easy access of the telehealth appointment and questioned why this option was not available for the initial visit or for other health issues. This topic arose without prompting and was present in the discussions with all 11 eleven participants. The identification of this theme shows support for easy access to telehealth appointments that could be applied to more than just positive STI screens. The telehealth component is convenient and immediate, in that the patient may sign on at their selected time in the comfort of the own home or a private location of their choosing. The appointments can be short, yet frequent assisting in educating the students and freeing bookable face-to-face time within the clinic. This case management model could potentially increase the numbers of individuals that the clinic reaches in providing guidance for prevention of numerous health issues. Training and implementing case management strategies, similar to those previously summarized, could be done for the entire nursing staff rather than one provider as stated in aim 1. The methods could be sustained within the health center in order to introduce students to sexual communication and create a means for long-term STI prevention.

In summary, the findings obtained in the project provide evidence that there is a desire to pursue sexual health appointments and STI checks if a telehealth platform is available. The students requested easy and immediate access to appointments for STI education and other general health questions. Initially, the pre SCSES revealed that students already possessed an ability to engage in communication with their partner about sexual topics. They revealed that they are comfortable in talking with partners and pursuing sexual relationships with others, initiating sex, and talking about what feels good sexually, regardless of risk. However, when provided education on those risks, they became more comfortable with also talking about who their partner had been intimate with or about protecting themselves. Although students stated many sexual communication topics were “easy” to talk about initially, the telehealth session implementation revealed that there was slight improvement in sexual self-efficacy. The implementation of effective case management strategies using telehealth support was successful in this project as noted by the pre and post SCSES results.

Ethical Considerations

Participation in this study was voluntary. Each individual who tested positive for an STI received a secure message through the electronic medical record portal, outlining the opportunity to enroll in a telehealth case management program in order to learn more about sexual communication and to assist health care staff in understanding sexual self-efficacy. The secure message explained that clicking on the Qualtrics link and completing the sexual selfefficacy questionnaire implied they consented to their enrollment in the program. Within this message, each participant was instructed that their medical record and any information obtained during the project would be kept secure, password protected, and confidential. Because of the sensitive nature of the topic, the participant could decline to answer or remove themselves from the project at any time.

Limitations

The generalizability of the information obtained in this project is limited as it reports on the perceptions of a small sample (N=11) of young adults at a public, Midwestern University. An ongoing case management model that allowed for more time to build rapport with the patient could have revealed different results. Additionally, the time frame when results were gathered took place in the summer, when many students return home and the University is not saturated with students testing positive for STIs.

Implications

The information obtained through this project provides insight into the level of self-efficacy young adults have with sexual communication. It revealed that while young adults feel comfortable talking about sex and engaging in risk taking behaviors, they are unaware of their risks. The telehealth session provided the information that young adults needed to empower themselves. Given the sensitive nature of the topic, ideally the program will be expanded to allow for more time. Then, the practitioner can build the rapport needed to gain trust from the patient and discuss sexual activities that could be placing them at risk. Additional research on a program that took place during the semester, when STI diagnoses are highest would be desirable [21-22].

The feedback from participants revealed that they are more likely to seek help for various health issues if access is easier. They expressed a desire to have telehealth available with any health concern they may have. The telehealth platform could be expanded to various diagnoses and performed by various practitioners. This could lead to further quality improvement projects, where the availability of telehealth could address certain issues, improve certain health concerns with this population, and in turn improve clinic access by relieving face-to-face time with practitioners.

Acknowledgment

None.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest.

References

- Eaton DK, Kann L, Kinchen S, Shanklin S, Flint KH, et al. (2012) Youth risk behavior surveillance-United States, 2011. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 61: 1-162.

- (2019) Healthy Campus 2020 [Internet]. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion.

- Lechner KE, Garcia CM, Frerich EA, Lust K, Eisenberg ME (2013) College students’ sexual health: Personal responsibility or the responsibility of the college? Journal of American College Health 61(1): 28-35.

- Donné L, Hoeks J, Jansen C (2017) Using a narrative to spark safer sex communication. Health Education Journal 76(6): 635-647.

- Bandura A (1994) Self-efficacy. New York, NY: Wiley.

- Quinn Nilas C, Milhausen R, Breur R, Bailey J, Pavlou M, et al. (2015) Validation of the sexual communication self-efficacy scale. Health Education and Behavior 43(2): 165-171.

- Halpern Felsher BL, Kropp RY, Boyer CB, Tschann JM, Ellen JM (2004) Adolescents’ self-efficacy to communicate about sex: Its role in condom attitudes, commitment and use. Adolescence 39(155): 443-456.

- Eisenberg ME, Hannan PJ, Lust KA, Lechner KE, Garcia C, et al. (2013) Sexual health resources at minnesota colleges: Associations with students' sexual health behaviors. Perspectives on Sexual & Reproductive Health 45(3): 132-138.

- McCutcheon T, Schaar G, Parker K (2016) Pender’s Health Promotion Model and HPV health-promoting behaviors among college-aged males: Concept integration. Journal of Theory Construction and Testing, 10(1): 12-19.

- Srof BJ (2016) Health promotion in adolescents: A review of Pender’s Health Promotion Model. Special Feature Penn State 19(4): 366-373.

- McCutcheon T (2014) Concept analysis: Health-promoting behaviors related to human papilloma virus (HPV) infection. Nursing Forum 50(2): 75-82.

- Myalgic Encephalomyelitis Action Network (2019) HIV/AIDS advocacy as a Model for catalyzing change, Lessons From the AIDS Movement retrieved from.

- Powell A, Valle C, Maheu C, Chalmers J, Sansom Daly U, et al. (2018) Psychosocial Assessment Using Telehealth in Adolescents and Young Adults with Cancer: A Partially Randomized Patient Preference Pilot Study. JMIR Research Protocols 7(8): E168.

- Van Volkom M, Stapley J, Malter J (2013) Use and perception of technology: Sex and Generational differences in a community sample. Educational Gerontology 39(10): 729-740.

- Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) (2019) Plan-Do-Study-Act Worksheet, Improving Health and Health Care Wordwide.

- Hsieh H, Shannon S (2015) Three approaches to qualitative content analysis, Qualitative Health Research 15(9): 1277-1288.

- Oklahoma State Department of Health (OSDH) (2019) Fact Sheets HIV/STD Service, Retrieved From.

- KOCO staff (2019) Congenital syphilis cases increase by 283% since 2014 in Oklahoma, officials say, KOCO News.

- Klein R, Knauper B (2003) The role of cognitive avoidance of STIs for discussing safer Sex practices and for condom use consistency. Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality 12 (3/4): 137-149.

- Alli F, Maharaj P, Vawda M (2013) Interpersonal relations between health care workers and Young clients: Barriers to accessing sexual and reproductive health care. Journal of Community Health 38(1): 150-155.

- American College Health Association National College Health Assessment Spring (2006) Reference Group Data Report (Abridged): The American College Health Association. Journal of American College Health 55(4): 195-206.

- University Health Services (UHS) (2019) Most frequent labs, version 1. Location: Point and Click electronic medical record.

-

Pamela Stokes. Increasing Sexual Self-Efficacy Among College Students Through Telehealth Consultation: A Case Management Page 7 of 7 Approach. Curr Tr Clin & Med Sci. 2(1): 2020. CTCMS.MS.ID.000530.

-

Telehealth, Sexually transmitted infections (STIs), Case management, Self-efficacy, Young adults, Health promotion, Disease, Public health

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.