Clinical case

Clinical case

Reverse or Restrict Liver Damage or Transplant the Liver in MASLD—Choice is Yours!

Suresh Kishanrao*

MD, DIH, FIAP, FIPHA, FISCD, Family Physician & Public Health Consultant, Bengaluru, Karnataka, India

Suresh Kishanrao, MD, DIH, FIAP, FIPHA, FISCD, Family Physician & Public Health Consultant, Bengaluru, Karnataka, India

Received Date:June 15, 2025; Published Date:July 07, 2025

Abstract

Marking its fifth edition on World Health Day, April 7, Apollo Hospitals’ Health of the Nation 2025 sheds light on the growing health crisis of Non-Communicable Diseases (NCDs) in general and draws attention in particular to the rise of metabolic dysfunction–associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD). Bengaluru City edition of Times of India on 13 June 2025 in an article titled “Sedentary Lifestyle leads to rise in non-alcoholic liver disease among young adults” highlighted that young people with symptoms of fatigue, occasional abdominal discomfort, on an abdominal scan or even in routine checkup are getting diagnosed having MASLD early stages. MASLD has far-reaching health consequences. Both these article appeal for an urgent need for both individual and collective action to combat them. The Health of Nation 2025 report emphasizes the need for ultrasound screenings to detect fatty livers even in cases where liver enzymes were normal. In 2024, 2.5 lakh individuals were screened, of which 65% had fatty liver despite 52% having normal liver enzyme levels.

A more startling update is that MASLD is not just alcohol-related! While alcohol is a known risk, non-alcoholic fatty liver is now more prevalent, mainly driven by obesity, diabetes and hypercholesterolemia. The trends of MASLD based on 2.5 L samples attending Apollo Hospitals Preventive Health Check Data indicated that 85% individuals with fatty liver cases were non-alcoholic individuals with obesity 76%, and 82% of diabetic individuals, 70% prediabetics and 52% of normo-glycemic and 74% individuals with hypertension had fatty liver. Global prevalence of MASLD has been estimated to be around 30%, lowest 13% in Sub Saharan Africa and highest 42.6% in Middle East and North Africa among general population, 68% to lowest 45% in Diabetes & Obese population in Latin America and Southeast Asia respectively and 68.7% among diabetics only in Middle East and North Africa. India, currently with an estimated pooled prevalence of 38.6% and possible geographic and rural-urban variations India, has a huge burden of MASLD.

Imaging-based screening, lifestyle changes, & targeted management to prevent complications are the ways for early control of metabolic dysfunction–associated steatotic liver disease. This article is influenced by reversing 2 cases of early stages of MASLD in young non-alcoholic executives with otherwise a healthy biomarker picture, identified in a routine health checkup, and managing another late-stage case with combined intervention of Live Donor Liver Transplant (LDLT) with sleeve gastrectomy (SG) supported by literature search, & review of recent specific guidelines form India and USA to manage MASLD.

Keywords: Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD); non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD); metabolic dysfunction– associated steatohepatitis (MASH); type 2 diabetes (T2D); obesity; living donor liver transplant (LDLT); sleeve gastrectomy (SG)

Introduction

An article titled Sedentary Lifestyle leads to rise in non-alcoholic liver disease among young adults on 13 June 2025 in Bengaluru City edition of Times of India highlighted that young people with symptoms of fatigue, occasional abdominal discomfort or a slightly abnormal abdominal scan report in routine checkup consult doctors and they are diagnosed as suffering from NASLD early stages. Many other cities and urban population experience similar problems worldwide. Health professional Clinicians in towns and cities report 30% rise increase in NASLD case after 2020-22 Covid 19 pandemic with a notable surge among adults in their 20’s and 30s. They also attribute it to long hours of desk work, increased processed food consumption, irregular meals obesity, and physical inactivity [1]. NASLD cases are being observed across socio-economic groups, affecting everybody with a sedentary lifestyle. “Health of the Nation 2025” report from Apollo Hospitals after screening 2.5 lakh individuals in 2024 put up startling information that 65% had fatty liver based on ultrasound, despite 52% having normal Biomarkers, drawing Nation’s attention to the rise of metabolic dysfunction associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) [2].

The good news is that MASLD is reversible it its’ early stages,

by changes in diet, increased physical activities, regular sleep and

reducing weight 5-10% [1]. On 12 May 2025, Indian diabetology

experts came out with a consensus statement for Management of

metabolic dysfunction–associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD).

Their statements point to:

a) Differences in diagnostic modalities & clinical

presentations contributing to variations in epidemiological

estimates, therefore, the need to revisit evolution and arrive at

clear diagnostic criteria, and the epidemiological estimates of

MASLD.

b) Concomitant with the increasing trend in obesity and

diabetes, MASLD has emerged as a public health concern in the

Indian population.

c) Promote the routine screening of people with T2D,

prediabetes, and /or obesity with cardiovascular risk factors,

with scanning or X ray of the liver with the goal of identifying

those with high-risk MASH and use of a graphic diagnostic

algorithm, that advises initial use of the noninvasive Fibrosis-4

(FIB-4) tool, which risk stratifies based on age, liver enzymes,

and platelet count.

d) Intervention aimed at preventing fibrosis progression and

cirrhosis, through reduction of body weight, lifestyle changes

like better diet and sleep promotion in the early stages and

pharmacotherapy and liver transplant in delayed cases [3].

Similarly, a new consensus report from the American Diabetes Association (ADA) provides a practice-oriented framework for screening and managing metabolic dysfunction–associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) in people with diabetes and prediabetes. Published online on May 28, 2025, in Diabetes Care, the update to the 2023 recommendations intended for clinicians treating patients with diabetes primarily type 2 diabetes (T2D) but also type 1 diabetes (T1D) with obesity and prediabetes [4]. Both documents provide primary care doctors & anyone taking care of people with diabetes, the tools to diagnose MASLD early & therapy to prevent cirrhosis & refer to the hepatologist as needed for additional therapy and monitoring. This article is an outcome of reversing 2 cases of early stages of NASLD after identifying in a routine health checkup in 2 mid-thirties non-alcoholic executives & managing another late-stage case with LDLT with sleeve gastrectomy (SG) following the recent global guidelines and other literature search.

Case Reports

Case 1: Accidental Discovery of NASLD in Annual Health Checkup

Dheeraj, a 33-year-old software engineer, went through an annual checkup, in October 2023, which revealed dyslipidemia (Total Cholesterol 250mg/dl, HDL 38 mg/dl, LDL= 140mg/dl, Triglycerides 170mg/ dl, HbA1c= 5.9) and abdominal scan reported Mild NASLD. Both parents being diabetic. He is a teetotaler but in terms of exercise was not regular. The scan report was alarming, and he was advised to lose 5 kg weight in the next 3 months, a diet rich in fruits, vegetables, & whole grains and limiting processed foods, sugary drinks, and regular exercise regimen which he followed meticulously. A repeat checkup in February 2024 brought all biomarkers under normal ranges except LDL which was 116mg/ dl. Scan indicated a normal liver.

Case 2: A Case of Non-Specific Symptom- Mere Fatigue Diagnosed as NASLD

Seema aged about 37 years, working as a teacher complained of Fatigue for about 2 months. On further inquiry she reported increased thirst, bloating of the abdomen frequently, sleep disturbances. General examination indicated that she was obese which was more evident on her waist and tummy. Abdominal palpation indicated mild aching to sharp pain in the upper abdomen. A random blood sugar tested 146 mg/dl suspecting Type 2 Diabetes. Her diet & exercise patterns recall indicated a high-fat diet and low physical inactivity which contributed to the accumulation of fat in the liver. Her blood biomarkers showed elevated liver enzymes (AST and ALT) and HbA1C was 7.1 mg/dl. An Ultrasound clearly showed moderately enlarged fatty liver. She was put on a standard restricted diet and advised regular aerobic exercises and stretch band and weight to strengthen muscles. She was prescribed “Resmetirom” 100 mg tablet, to treat liver fibrosis. Over the period of the next 6 months, she reduced her weight by 15 kgs and feels fit with Hb1Ac coming under 6.2mg/dl and liver fibrosis not progressing.

Case 3: A MORBIDLY OBESE DIABETIC Man with NASLD for Liver Transplantation

A morbidly obese diabetic man presented to me in Indian diabetic foundation clinic in Delhi with complaints of Musculoskeletal complaints, and restricted mobility in January 2017. He was diagnosed with F4 NASLD after blood test and scanning of the abdomen and advised diet and Resmetirom” 100 mg tablet therapy in 2006 in Delhi. However, after 6 months of trial no significant weight loss or relief of symptoms occurred. Therefore, he was referred to Liver & Biliary disease hospital. There he was operated on combining living donor liver transplant (LDLT) with sleeve gastrectomy (SG). Postoperatively, with liver graft functioning adequately, bariatric diet restrictions resulted in maximum reduction of 25% weight, achieving a target BMI below 30 kg/m2 within 2 months, along with complete cure of diabetes and better ambulation. LDLT and bariatric surgery in the same sitting is safe and effective in management NASLD. Regular Checkups monitoring liver function, blood pressure, cholesterol levels, and other relevant parameters helped his survival till 2021.

Discussion

The increasing prevalence of diabetes and obesity poses a significant public health threat towards a surge in the incidence of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD), formerly known as non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). It is affecting all socioeconomic groups be it a Paan shop owner, auto & cab drivers, financial executives or all white collared professionals working from home or offices sitting for long hours, for that matter to every desk worker with a sedentary lifestyle. Recent pathophysiology studies have linked obesity & dietary composition, ethnicity & genetic factors to the risk of MASLD [1,2].

Terminology Change

Highlighting Insulin Resistance, Reducing Stigma of alcoholics, the nomenclature was Metabolic Hepatitis until 2002 (American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases), changed to Metabolic Fatty Liver Disease (MFLD- EASL, European Association for the Study of the Liver) in 2011. It was known as Metabolic syndrome associated fatty liver disease- MSAFLD- Balmer & Dufour), that was changed to metabolic dysfunction–associated Fatty liver disease (MAFLD-22 International experts) in 2020, & finally to metabolic dysfunction –associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) in 2023. The current nomenclature for SLD, officially changed in 2023 by removing the words “fatty” and “alcoholic.” Now, MASLD is defined as the presence of SLD with at least one metabolic risk factorsobesity, hypertension, prediabetes, T2D, > triglycerides, low high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, with minimal or no alcohol consumption (< 20 g/d for women; < 30 g/d for men) [4].

The term “MetALD” is used for those with MASLD who also have increased alcohol consumption (20-50 g/d for women; 30-60 g/ day for men). Steatosis in the setting of alcohol consumption above those levels is termed “alcohol-associated liver disease (ALD).” The term MASH is defined as steatohepatitis with at least one metabolic risk factor and minimal alcohol consumption. “At-risk MASH” refers to steatohepatitis with clinically significant fibrosis (stage F2 or higher) [4]. Global prevalence of MASLD has been put between 13% in Sub Saharan Africa and highest 42.6% in Middle East and North Africa in general population, 68% in Diabetes and Obese population in Latin America and 45% in Southeast Asia including India to highest 68.7% among diabetics in Middle East and North Africa [4].

Burden of MASLD in India

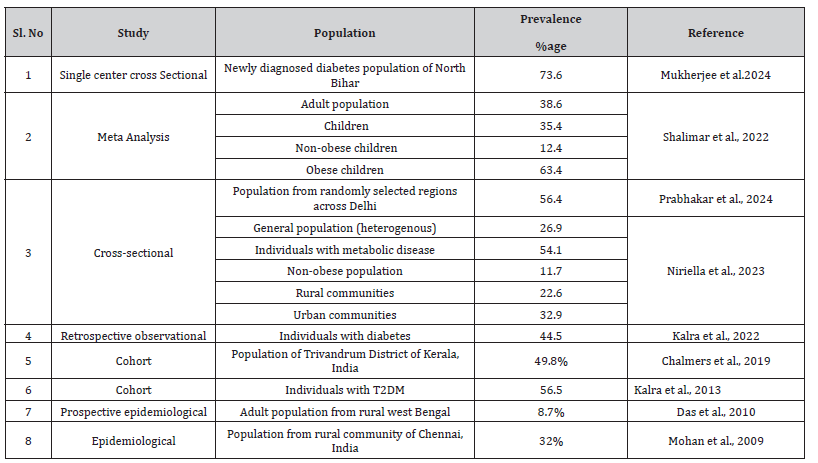

MASLD, previously known as non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), in India is approximately 38.6% among adults. This translates to a significant burden of the disease in India, with potential geographic and rural-urban variations. In India, the increasing prevalence of diabetes and obesity poses a significant threat towards a surge in the incidence of metabolic dysfunctionassociated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) [3] (Table 1).

Table 1:Indian prevalence estimates of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD).

Epidemiology Global

MASLD has been estimated to affect 30% of the adult population worldwide, with its prevalence increasing from 22% to 37% from 1991 to 2019. MASLD is following the increasing prevalence of obesity and obesity-related diseases. Metabolic dysfunctionassociated steatohepatitis (MASH) is the more severe form, defined histologically by the presence of lobular inflammation and hepatocyte ballooning, and it is associated with a greater risk of fibrosis progression. MASH has been found in 63% of patients with MASLD undergoing liver biopsy in an Asian multi-center cohort. CVD, Liver fibrosis & renal failure are the leading causes of mortality among these patients [4]..

India

India, currently the most populous country in the world, has a huge burden of metabolic dysfunction associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD), with an estimated pooled prevalence of 38.6% and possible geographic and rural-urban variations [3]. Given the large population and the alarmingly high prevalence of MASLD in the country, India is home to one of the highest numbers of patients with MASLD in the world, with huge implications for clinical practice in India. This is further compounded by the recent guidance document by the Indian National Association for Study on Liver (INASL) and Indian diabetologists perspectives which were published recently [3,8].

Pathophysiology

The central theme in the pathogenesis of MASLD leading to the development of hepatic steatosis is the dysregulation of fatty acid metabolism in the liver, which disrupts the harmony of energy generation and lipid storage mechanisms. In the early 2000s, pathogenesis of NAFLD was explained by the ‘two-hit hypothesis’ that attributes the development of fatty liver to (a) excessive hepatic lipid deposition and (b) subsequent activation of inflammatory cascades, oxidative stress and fibrogenesis in hepatocytes. However, recent research paved the way for understanding more complex molecular and metabolic changes associated with a broader range of risk factors of NAFLD, leading to a ‘multi-hit theory’. This theory identifies insulin resistance, dietary influences, hyperglycemia, dyslipidemia, genetic predispositions and epigenetic modifications as lead factors. MASLD is an outcome of ectopic fat accumulation in the liver due to adipocyte insulin resistance, thereby diverting free fatty acids from adipocytes to the liver. In contrast, metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH) is a result of toxic effects of accumulated lipids in the liver, referred to as hepatic lip toxicity. Genetically susceptible individuals with unfavorable environmental factors like inappropriate diet, lack of physical activity and air pollution are at high risk for MASLD. Recent studies from India have shown a strong association between PM2.5 (particulate matter) levels and incident of type 2 diabetes, lipid abnormalities and hypertension. These are also key metabolic abnormalities in MASLD with respect to air pollution [3].

Diagnosis

MASLD is diagnosed if Hepatic steatosis detected mostly by imaging techniques, or blood biomarkers/scores, or liver history plus (i) Overweight or obese,(ii) Type 2 diabetes mellitus or (iii) Presence of ≤ 2 metabolic risk abnormalities among: (a) Waist circumference ≥ 90/80 cm in Asian men & women b) Blood pressure ≥ 130/85 mmHg or specific drug treatment c) Plasma triglycerides ≥ 150 mg/dL ( ≥ 1.70 mmol/L) or specific drug treatment d) Plasma HDL cholesterol < 40 mg/dL (< 1.0 mmol/L) for men and < 50 mg/dL (< 1.3 mmol/L) for women or specific drug treatment e) Prediabetes (i.e., fasting glucose levels 100–125 mg/dL [5.6–6.9 mmol/L], or 2-hour post-load glucose levels 140–199 mg/dL [7.8– 11.0 mmol], or HbA1c 5.7%–6.4%) f) HOMA-IR, homeostatic model for assessment of insulin resistance- (HOMA-IR) ≥ 2.5 g) Plasma high sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP-level > 2 mg/L and presence of other concomitant liver diseases retaining their own term [3,4,6].

Staged Screening for Fibrosis

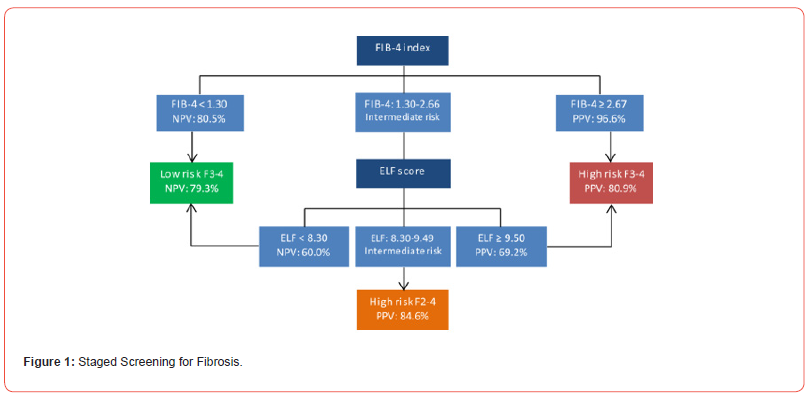

The routine screening of people with T2D, prediabetes, and/or obesity with cardiovascular risk factors, with the goal of identifying those with high-risk MASH. Intervention is then aimed at preventing fibrosis progression and cirrhosis. A graphic diagnostic algorithm advises initial use of the noninvasive Fibrosis-4 (FIB-4) tool, which risk stratifies based on age, liver enzymes, and platelet count [3,4] (Figure 1).

FAB Formula

The FIB-4 index is a non-invasive tool used to assess liver fibrosis, particularly in patients with viral hepatitis or other liver diseases. It calculates a score based on readily available laboratory data like age, AST (aspartate aminotransferase), ALT (alanine aminotransferase), & platelet count. The index helps to determine the likelihood of advanced fibrosis - bridging fibrosis or cirrhosis. Scores are interpreted based on cut-off values. For example, a score below 1.45 indicates a low risk of advanced fibrosis, while a score > 3.25 indicates a higher risk. Those with a FIB-4 < 1.3 have a low risk for future cirrhosis and can be managed in primary or team care with optimized lifestyle and repeated FIB-4 every 1-2 years. If the FIB-4 is > 2.67, direct referral to a liver specialist is advised. If FIB-4 is between 1.3 and 2.67.

A second risk-stratification test Ideally, a liver stiffness

measurement (LSM), with transient elastography or, a noninvasive

enhanced liver fibrosis (ELF) test is recommended.

a) Non-invasive Tests for hepatic fibrosis: Non-invasive

tests for hepatic fibrosis include serologic tests and imaging

techniques like elastography. Serologic tests assess liver

function and fibrosis, while elastography measures liver

stiffness [4].

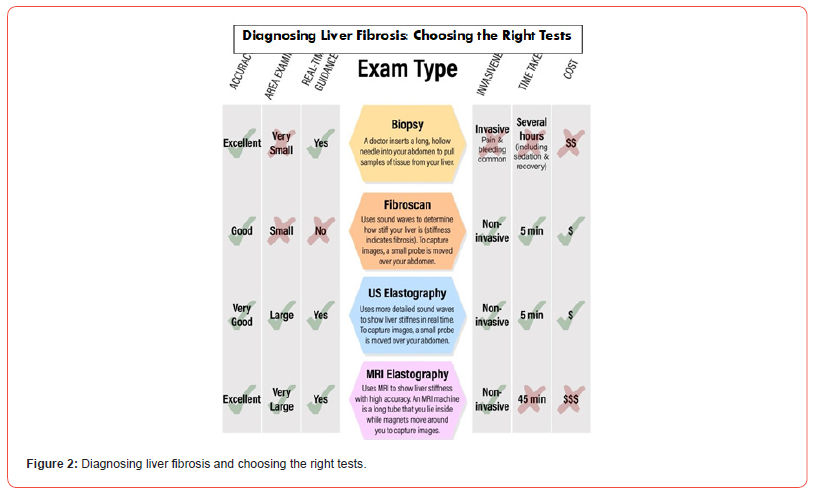

b) Elastography: Transient Elastography (Fibroscan): A

non-invasive method that measures liver stiffness by using a

vibration-controlled probe. It is a widely used and accurate test

for assessing fibrosis, especially in patients with chronic liver

diseases (Figure 2).

c) Magnetic Resonance Elastography (MRE): An imaging

technique that uses MRI to measure liver stiffness and fibrosis.

d) Acoustic Radiation Force Impulse (ARFI) Imaging: An

ultrasound-based technique that measures shear wave velocity

in the liver to assess fibrosis.

e) Two-Dimensional Shear Wave Elastography (2D-SWE):

An ultrasound-based technique that measures shear wave

velocity in multiple frequencies to assess fibrosis.

f) Point Shear Wave Elastography (pSWE): An ultrasoundbased

technique that measures shear wave velocity at a single

point in the liver to assess fibrosis.

g) Real-time Strain Elastography: This technique uses

standard ultrasound to measure liver tissue displacement

(strain) induced by a probe or cardiac impulse.

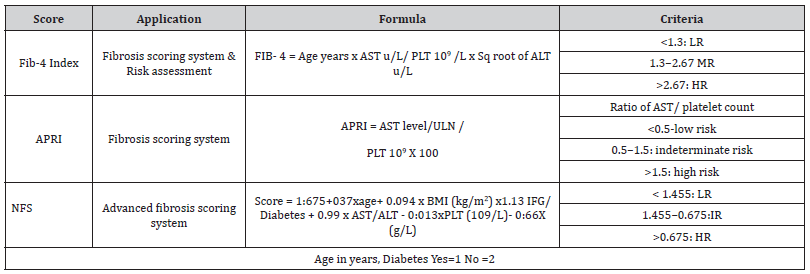

Serologic Tests APRI (AST-to-Platelet Ratio Index) and FIB-4 (Fibrosis-4 Score)

Simple, widely used scores that can be calculated from routine

blood tests.

a) Enhanced Liver Fibrosis (ELF): A proprietary blood test

that measures three fibrosis markers: HA, PIIINP, and TIMP-1.

b) FibroTest: A commercially available test that requires

specific laboratory tests for markers like haptoglobin and

alpha2-macroglobulin.

Other Non-invasive Tests

a) Abdominal Ultrasound: A common initial test to assess

liver disease.

b) MRI or CT Scanning: Imaging techniques that provide

details about the liver structure.

c) Genetic Signature Scores: Emerging tests that analyze

genetic markers and gut microbiome profiles to assess fibrosis.

If the LSM is < 8.0 kPa or ELF is < 7.7, the fibrosis risk is low, and routine management can continue with repeat testing in 1-2 years. But if LSM is higher than 8 kPa or ELF>7.7, hepatology referral is recommended [4,6].

Indian Guidelines for Diagnosis

Indian expert group recommends considering following factors while screening for disease, progression of MASLD. In Indian clinical practice, vibration controlled transient elastography (VCTE) remains the best-validated imaging modality for the diagnosis and staging of disease progression of MASLD. Acoustic radiation force impulse (ARFI) imaging is an emerging tool for the diagnosis of MASLD. If VCTE is not available or accessible, the assessment of liver steatosis and fibrosis should rely on multiple modalities, including imaging and testing for serological markers. Fibrosisindex- 4 [derived from age, Aspartate Aminotransferase (AST), Alanine Aminotransferase (ALT) and platelet] is a useful prognostic tool for screening and risk stratification.

Criteria

a) Anyone with liver steatosis on imaging

b) Unexplained elevation in liver enzymes (plasma

aminotransferase levels [>30 U/L])

c) First-degree relative of a patient with MASLD/cirrhosis

d) Anyone with one or more of the following risk factors

a. Overweight or obese individuals (Asian Indian Body Mass

Index criteria: BMI >23 kg/m2)

b. Waist circumference ≥90 cm in men and ≥80 cm in

women.

c. Prediabetes or type 2 diabetes (T2DM) or treatment for

diabetes.

d. Plasma triglycerides ≥1.7 mmol/L (≥150 mg/dL) or on

lipid lowering treatment.

e. HDL-cholesterol ≤1.0 mmol/L (≤40 mg/dL) in men &

and ≤1.3 mmol/L (≤50 mg/dL) in women or on lipid lowering

treatment.

f. BP ≥130/85 mmHg or on treatment for hypertension.

It Also, advised to screen all individuals with

a) polycystic ovarian syndrome

b) Obstructive sleep apnea

c) chronic kidney disease

d) History of cholecystectomy

e) HIV infection

Screening criteria for metabolic dysfunction–associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) [3,4,6] (Table 2).

Table 2:Scoring systems in metabolic dysfunction–associated steatotic liver disease.

Cardiometabolic criteria for Asian Indian adults: ALD, alcoholrelated liver disease; BMI, body mass index; BP, blood pressure; DILI, drug-induced liver injury; F, female; HbA1c, glycated hemoglobin; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; M, male; MetALD, metabolic dysfunction & alcohol-related liver disease; SLD, steatotic liver disease; WC, waist circumference.

Waist-to-Height Ratio-A Simple Tool useful in Clinical & Public Health Practice for Liver Disease Screening, Prevention, Diagnosis and Management

Previous studies in adults have shown that BMI-diagnosed obesity is a risk factor for liver steatosis. Following a recent clinical consensus that obesity should be screened with BMI but confirmed with waist-to-height ratio or transient elastography. Waist-toheight ratio is a cheap and universally accessible tool to detect the risk of fatty liver disease both in the young and adult population reported a new study. The study conducted at the University of Eastern Finland, and the results were published in the Journal of the Endocrine Society. In the present study, 6,464 children, adolescents and adults between 12 and 80 years of age drawn from the United States National Health & Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) conducted between 2021 and 2023, Non-invasive liver scans were conducted in all participants by, based on which their risk of liver steatosis or fibrosis was classified. The prevalence of significant or advanced liver fibrosis was 7.1%, while 4.9% had liver cirrhosis. More than 1 in 4 (26.1%) participants had suspected liver steatosis, while less than 1% had severe liver steatosis. This recent study discovered that waist-to-height ratio was a highly sensitive and specific predictor of dual-energy Xray absorptiometry-measured total body fat mass and abdominal fat mass in the pediatric and young adult population.

Waist-to-height ratio cut points for normal, high & excess fat mass were established & have since been validated to detect the risk of type 2 diabetes & bone fracture. This study examined if these cut points can predict liver steatosis & fibrosis in a multiracial population. The prevalence of waist-to-height-ratio-estimated normal fat mass (0.40 - <0.50), high fat mass (0.5 - <0.53), excess fat mass indicating obesity (≥0.53) was 20.3%, 13.6% &64.5%, respectively. After full adjustments for covariates, normal fat mass had a 48% protective effect against liver steatosis and a 52% protective effect against liver fibrosis or cirrhosis. High fat mass predicted 63% higher odds of liver steatosis &31% higher odds of liver fibrosis or cirrhosis. Excess fat mass predicted four-fold higher odds of liver steatosis& 61% higher odds of liver fibrosis or cirrhosis. Waist-to-height-ratio-estimated high fat mass and excess fat mass separately predicted higher odds of liver steatosis nearly two-fold and six-fold, respectively, better than BMI-overweight and BMI-obesity. The study accounted for age, sex, systolic blood pressure, heart rate, educational status, smoking status, race, sedentary time, moderate physical activity, fasting insulin, glucose, total cholesterol and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein. The findings were consistent regardless of sex & age. Therefore, waistto- height measurement is recommended as useful tools in clinical & public health practice for liver disease screening, diagnosis & management globally [5,8].

Management

USA, UK and Indian group’s recommendations include i) Early lifestyle interventions including weight loss and exercise ii) The pharmacological landscape of drugs directed to insulin resistance, lipid metabolism, oxidative stress, inflammation, apoptosis and fibrogenesis pathways for the management of MASLD [3,4,8,9].

Weigh Loss Management

The first and most important steps in the management of MASLD are intensive lifestyle modification. Weight loss management through lifestyle modifications is the cornerstone of treatment in MASLD patients. Quantitatively, a weight loss of ≥5%, 7%–10% and ≥10%, is associated with a reduction in steatosis, an improvement in steatohepatitis and an improvement in fibrosis, respectively. Lifestyle modification or MASLD includes nutrition plans; physical activity; behavioral health; and promoting diabetes self-management, education and support. The role of obesity treatment in people with MASLD, both surgery & pharmacotherapy, adds value to the management [3,4].

Diet and Exercise

Diet and exercise reduce liver fat in normal-weight individuals with MASLD. Adopting a low-calorie, low-fat, low glycemic index diet & increased physical activity reverse early histologic damage associated with MASLD [4]. Indian diet predominantly consists of cereals and whole grains (50%–70%), while often falling short of the recommended intake of proteins, fruits and vegetables and according to the EAT-LANCET Commission report, the diet across different Indian states and income groups is largely unhealthy. The Indian Council of Medical Research-National Institute of Nutrition (ICMR-NIN) recommends minimizing the consumption of ultra processed foods and foods high in fat, sugar and salt to reduce the risk of non-communicable diseases in general. The Indian Council of Medical Research–India Diabetes (ICMR-INDIAB) study, revealed that approximately 101 million people are living with diabetes and 136 million with prediabetes, a high prevalence of abdominal obesity (351 million individuals) and hypertension (315 million individuals). Dietary analysis from the study indicated an excessively high carbohydrate intake, comprising 60%–70% of total energy, while consumption of protein and dietary fiber was low.

The study recommended that substituting 10%–15% of refined carbohydrates—particularly those with a high glycemic index—with plant-based protein sources and incorporating monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fats which will significantly contribute to lowering the burden of metabolic NCDs in India. ADA recommends Mediterranean diets, characterized by a high intake of olive oil (rich in monounsaturated fatty acids) and fish (rich in omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids) and vegetarian diets that are rich in dietary fiber, polyphenols, folate and carotenoids, to offer hepatic benefits in MASLD and provide cardiovascular protection. Conversely, diets high in red and processed meats (rich in saturated fats), as well as sugars (fructose) have been linked to the development of MASLD. The World Health Organization (WHO) noted the extent of insufficient physical activity and recommended almost doubled among the Indian population from 22% in 2000 to 49% in 2022. This further contributes to the disease burden of the country. Regular physical activity improves body composition, enhances insulin sensitivity in the liver and adipose tissues and may exert benefits independent of weight loss.

Combining aerobic exercise and resistance training reduces steatosis and improves cardiometabolic outcomes. Exercise has been shown to increase butyrate production, which supports colonic epithelial cell health, enhances mucosal immunity and reduces pathogens. It also boosts primary bile acid secretion, promotes cholesterol turnover, fosters the growth of beneficial bacteria and affects gut transit time and substrate delivery to microbiota. Some studies suggest that an intake of ≥3 cups of coffee per day may be beneficial 3,9].

Pharmacotherapy

No current pharmacologic treatments have been approved for MASLD. But both Semaglutide and Tirzepatide have demonstrated benefit in treating MASH and are approved for treating T2D, obesity, and other related comorbidities. A thyroid hormone receptor beta agonist, Resmetirom, was approved in early 2024 for the treatment of MASH with fibrosis stages F2 and F3 but is extremely expensive at about $50,000 a year. An older, generic glucose-lowering drug, Pioglitazone, has also shown benefit in reducing fibrosis and may be a lower-cost alternative 3,4]. A study of 210 participants with women comprising 62.9% and majority of participants were Hindus (56.7%) followed by Christians (31.4%) and Muslims (11.9%). Most participants belonged to socioeconomic class II (43.8%) closely followed by socioeconomic class III (37.6%). Around 11.9% belonged to class IV, 2.4% to socioeconomic class V and 4.3% to socioeconomic class I by BG Prasad classification. The overall prevalence of NAFLD was 34.8%. The prevalence among men (46.2%) was significantly higher (p=0.008) than among women (28%). Break-up by grading 57.5% were mild, 38.4% moderate and 4.1% were severe. Individuals >35 years of age had higher prevalence (39.4%) compared to those <35 years (6.7%).

The highest prevalence was among Hindus (38.7%) followed by Christians (36.4%) and the lowest among Muslims (12%). Higher prevalence was observed among higher socioeconomic classes I (44.4%) and II (48.9%). and low in the lower socioeconomic classes IV (4.0%) and V (20%). Individuals consuming a non-vegetarian diet were twice as likely to have NAFLD compared to vegetarians (OR 2.83). The prevalence of NAFLD was significantly higher (p=0.0001) among people with diabetes (52.1%) and hypertensives compared to those without diabetes and normotensives [7].

American Diabetes Association’s guidelines

A new consensus report from the American Diabetes Association (ADA) provides a practice-oriented framework for screening and managing metabolic dysfunction–associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) in people with diabetes and prediabetes. This provides primary care doctors and anyone taking care of people with diabetes to diagnose [MASLD] early and guide therapy to prevent cirrhosis and refers to the hepatologist as needed for additional therapy and monitoring. The guidelines recommend that clinicians routinely screen people with T2D or prediabetes for MASLD; by incorporating liver into management in the same way clinicians do chronic kidney disease, eye disease, and nerve disease as an endorgan damage that is particularly affected by diabetes [4]. Liver disease has not been a focus of diabetes management until recently, General duty doctor or Primary Care Physicians don’t think about it. The epidemic of obesity, and diabetes, have been causing this liver disease since the 1990s, so this damage in the past 35 years is evident in the liver now [3,4,9,10].

Conclusion

MASLD has been estimated to affect 30% of the adult population worldwide, and an estimated pooled prevalence of 38.6% with possible geographic and rural-urban variations in India! with far-reaching health consequences. In India most cases are being diagnosed in young people in routine checkups or with symptoms of fatigue, occasional abdominal discomfort, after an abdominal scanning. MASLD is diagnosed mostly by imaging techniques, blood biomarkers/scores, or liver history, overweight or obese, T2D and presence of ≥ 2 metabolic risk abnormalities. Waist-to-height ratio has been recommended as a simple Tool useful in clinical & public health practice for liver disease screening, prevention, diagnosis and management. The central theme in the pathogenesis of MASLD leading to the development of hepatic steatosis is the dysregulation of fatty acid metabolism in the liver, which disrupts the harmony of energy generation and lipid storage mechanisms. The good news is MASLD is reversible in early stages, damage can be arrested in moderate level and need liver transplantation in later stages. MASLD management recommendations include 1) Early lifestyle interventions like losing weight and exercise 2) The pharmacological landscape of drugs directed to insulin resistance, lipid metabolism, oxidative stress, inflammation, apoptosis and fibrogenesis pathways and 3) Live donor liver transplantation in very late stages. The clinicians must routinely screen people with T2D or prediabetes for MASLD by incorporating liver management in the same way, they do chronic kidney disease, eye disease, & peripheral nerve disease as an end-organ damage affected by diabetes. There is an urgent need for both individual & collective action by all countries to combat MASLD

References

- Yashaswini (2025) Sedentary Lifestyle leads to rise in non-alcoholic liver disease among young adults.

- Health of the nation (2025) Navigating Indian health landscape.

- Viswanathan Mohan (2025) Management of metabolic dysfunction–associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD)— Indian diabetologists' perspective. Diabetes, Obesity and Metabolism 27(4): 3-20.

- Miriam E. Tucker (2025) ADA Issues New MASLD Guidelines.

- (2025) Waist Size Relative to Height Signals Liver Trouble Better than BMI.

- Wah-Kheong Chan, Kee-Huat Chuah, Ruveena Bhavani Rajaram, Lee-Ling Lim, Jeyakantha Ratnasingam, et al. (2023) Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease (MASLD). J Obes Metab Syndr 32(3): 197-213.

- Prajakta Ankur Vagurmekar, Agnelo Menino Ferreira, Frederick Satiro Vaz, Hemangini Kishore Shah, Amit Savio Dias, et al. (2023) Prevalence of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) among adults in urban Goa. Natl Med J India 36(6): 401-404.

- Swarup K. Chakrabarti, Dhrubajyoti Chattopadhyay (2025) International Journal of Clinical Case Reports and Investigations Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in India: Mechanisms and Metabolic Signatures.

- Childhood obesity in India, Sakshi Singh (2023) Childhood obesity in India: A two-decade meta-analysis of prevalence and socioeconomic correlates. Clinical Epidemiology & Global Health.

- Steven M Schwarz (2023) Obesity in Children.

-

Suresh Kishanrao*. Reverse or Restrict Liver Damage or Transplant the Liver in MASLD—Choice is Yours!. Curr Tr Clin & Med Sci. 4(2): 2025. CTCMS.MS.ID.000585.

-

Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD); non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD); metabolic dysfunction–associated steatohepatitis (MASH); type 2 diabetes (T2D); obesity; living donor liver transplant (LDLT); sleeve gastrectomy (SG); iris publishers; iris publisher’s group

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.