Case Report

Case Report

Reading at Grade Level by Third Grade: A Multi-Level Life Course Framework

Danielle Gilmore*

Trachtenberg School of Public Policy and Administration, George Washington University, USA

Danielle Gilmore, Trachtenberg School of Public Policy and Administration, George Washington University, USA.

Received Date: February 11, 2022; Published Date: February 23, 2022

Introduction

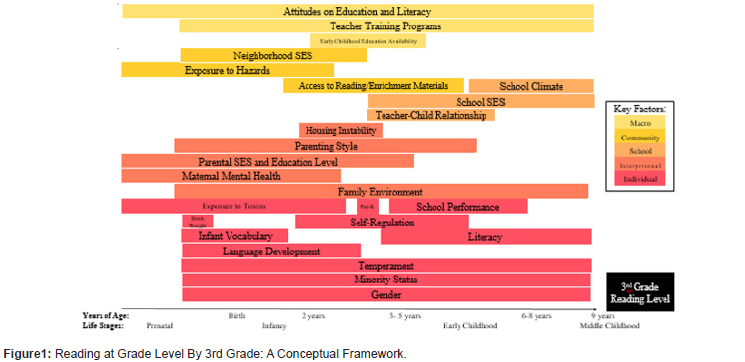

This multi-level life course framework (framework) attempts to explain influences that impact reading proficiency for third grade students through examining macro, community, school, interpersonal and individual level factors..

Rationale: Why Third Grade?

In third grade, children begin shifting from learning to read to reading to learn [1,2]. Children who are not reading at grade level by the end of third grade often remain to behind their peers as they progress through school [1].

Defining Timeline: Infancy, Early Childhood and Middle Childhood

For the purposes of this framework model, stages of child development are defined as follows. Infancy is from birth to two years of life. Early childhood is from age three to eight. Middle childhood is from age nine to 11 culminates at 11 years old, with the onset of late childhood or adolescence (American Association for the Advancement of Science).

Factors and Influences on Third Grade Reading Proficiency

Macro Level

Macro level factors include cultural, political and systemic influences [3]. It includes cultural attitudes surrounding education and literacy; teacher training programs; early childhood education program funding and availability

In societies with more rigid gender roles, (i.e. masculine societies) males are typically afforded greater access to resources and higher paying jobs. Researchers Chiu, et al. [4] examined adolescents’ reading achievement from 41 countries. They discovered girls perform lower on reading tests in masculine societies. They also found the reading achievement gap between one and two parent households was less pronounced in collectivistic cultures [4]. Teacher training programs are directly correlated with student’s learning outcomes. The Chicago School Readiness Project (CSRP) randomly increased funding for certain Head Start programs to provide teacher trainings. Through teacher training programs CSRP was able to increase school readiness in low income students [5]. According to United States census data, there are less early childhood education centers in low socioeconomic status (SES) neighborhoods compared to higher SES neighborhoods. Because, “parents in low SES-neighborhoods are less likely to be employed full time than those in high-SES neighborhoods and therefore are less likely to use [early childhood education and care] to seek to support employment and/or less likely to use it for fewer hours each week” [6]. The reduced demand for these services results in a diminished supply. Additionally, these services tend to be less quality in low income neighborhoods [6].

Community Level

Community level factors include proximal environmental influences [3]. These factors include neighborhood SES, exposure to hazards and access to reading or enrichment materials, among others. Neighborhood SES can inform the type of hazards children experience. Children in low SES communities may be exposed to violence or drugs, which may result in post-traumatic stress like symptoms and significantly impact the brain development. High poverty neighborhoods are associated with a nine-fold increase in lead prevalence [7]. Furthermore, children in low SES families have less access to learning and stimulating materials [7]. According to [8] “the average U.S. middle income child has access to 12 books, but in low income neighborhoods there is about one book for every 355 children (p. 8). Thus, the ability to develop proficient reading abilities can be significantly enhanced or hindered by one’s neighborhood of residents.

School Level

School level factors involve academic related influences that affect one’s ability to learn. These factors include school SES, school climate, and teacher-child relationship. School SES is directly correlated with the resources available to the school, faculty and students. Low performing schools are typically located within low income neighborhoods [1]. School climate refers to the overall environment within a learning institution. It can serve as a facilitator or barrier in engaging and motivating students to learn. Teachers’ roles are especially fundamental in the development of school climates [5]. Evidence shows classroom quality and relationships with teachers have been shown to influence students’ academic outcomes [9]. Closer teacher-child relationships result in increased school readiness, higher academic performance, reduced behavioral problems [10].

Interpersonal Level/

Interpersonal level factors refer to the relationship or social influences associated with an outcome of interest [3]. Family level factors are among the most critical influences of language development and literacy in childhood. These factors include, but are not limited to housing instability, parenting style, parental SES and education level, maternal mental health and family environment. Housing instability is defined as moving at least three times over a child’s lifetime. According to Current Population Survey data, 42% of households that reported moving had children under age 6, suggesting housing instability is highest among families with preschool aged children. Housing instability during infancy and early childhood adversely impact social, emotional and cognitive development resulting in diminished school readiness and academic achievement [11]. Until age seven, the developing pre-frontal cortex can be significantly influenced by parents and other caregivers. Parenting style is strongly correlated with child’s development of executive functioning. Executive functioning is linked to critical thinking, reading and math proficiency, verbal and nonverbal reasoning, academic achievement, communication and social skills [12]. Strict or more intrusive parenting styles are associated with poorer child outcomes including worse language development and increased externalizing behavior problems [13]..

Income and education have a substantial impact on one’s employment, housing, transportation and other social determinants of health. Children from low SES backgrounds are at higher risk for developing poor self-regulation (SR) due to exposure to factors associated with poverty like poor neighborhood quality [6,14]. Results from a three-generation prospective longitudinal survey show individuals with higher income and education had grandchildren with more advanced vocabulary development. Children with limited vocabulary have more difficulty in school which worsens as students’ progress through school [15]. Maternal mental health is an important factor in development. A study conducted [16], revealed children of mothers with poor mental health outcomes during early childhood, had higher cortisol levels at school age. Depressed mothers are less likely to engage with and respond to their children inhibiting the development of executive functioning, working memory and other skills related to later school success [16]. Previous studies have also study by linked maternal stress and depression in utero and early childhood to behavioral problems in middle and late childhood [17-19] conducted a study to examine the influence of family environment for adopted children. The study revealed family environment affects child outcomes independent of genetic influences. High levels of family dysfunction can increase cortisol levels and impair brain development [16]. Additionally, research shows children who have one strong positive parental relationship can be buffered from the harmful effects of the unhealthy relationship with the other parent or caregivers [17].

Individual Level

One cannot build a framework without compassing the individual level factors that impact reading proficiency. These factors are included by not limited to toxin exposure, birth weight, temperament, infant vocabulary, SR, language development, prekindergarten attendance, school performance, literacy, minority status and gender.

Exposures to toxins in utero and early childhood including lead, alcohol, and stress adversely impact cognitive development and academic performance, even among children from middle- and upper-income families [20,21]. Researchers [21], found “significant associations between early childhood lead exposure and academic achievement” which follow a dose-response pattern (p. e75). Children of mothers who drank heavily during pregnancy were twice as likely to read below proficiency. Exposure to elevated levels of cortisol and other stress hormones can result in toxic stress which damages prefrontal cortex, hypothalamus and other architecture of the developing brain [16]. In addition, premature birth is a “clear predictor of early school performance” [22]. Children born prematurely are more likely to be low birth weight, placing them at a significant risk of delayed language development [23]. Children who are slow to develop spoken language in the absence of any known cause (e.g. developmental disabilities) are at increased risk for developing reading difficulties by school age [24].

SR or the intentional adaptation and response to external stimuli is a predictor of academic success [25,26]. Children with higher SR have better working memory and impulse control, perform better at tasks integrating multiple skills [25], and have higher classroom engagement and academic achievement [26]. Language development is also “an important component of school readiness and later academic success[13]. If children lack the language skills to understand instruction and communicate effectively, they will struggle throughout school and the life course. Pre-school can provide children with support needed to be more adequately prepared for school. Students who attend Head Start, an early childhood education program for low income children have higher social skills and more established cognitive development [27]. Preschool attendance is also correlated with the early development of literacy skills ultimately improving school readiness [28].

Performance in kindergarten through second grade is strong predictor of future school performance. Students with subpar academic performance typically fail to catch up as they continue through school [1]. When investigating influences on reading level for third graders, one must account for literacy level. Students who have developed literacy early or those with more established literacy skills have improved school readiness and better academic outcomes [28].

Temperament is defined as “the manner in which an individual reacts with and responses to social and emotional environmental cues” [18]. It is established in infancy and remains fairly stable throughout life course. Temperament is a primary determinant in the development SR [14]. Preschool attendance is correlated with improved language development and the early development of literacy skills. Children in low income families have less access to resource dense environments [1]; are more likely to born prematurely [22] or exposed to toxins including lead and prenatal alcohol exposure [20]; and experience housing instability [11] or increased family dysfunction [21]. Consequently, low income children are less ready for school and have lower reading proficiency than their affluent peers. These effects are further compounded by race and ethnicity, especially because many factors associated with low SES are also associated with minority status. Research shows African American and Latino/a students who poor readers in third grade are less likely to complete high school than White students performing at the same reading level [1].

Role of Early Childhood Interventions

Implementing prevention programs before third grade can increase proficiency of 85- 90% of poor readers. However, if interventions are implemented after third grade 75% of children will still continue to have reading difficulties [2]. Literacy development has a critical period and to maximize the effectiveness of an intervention policy makers should intervene as early in the life course as possible. Thus, high quality early childhood interventions are key to improving reading proficiency among children [10,29] (Figure 1).

Acknowledgment

None.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of Interest.

References

- Hernandez DJ (2011) Double Jeopardy: How Third-Grade Reading Skills and Poverty Influence High School Graduation. Annie E. Casey Foundation.

- Lesnick J, Goerge R, Smithgall C, Gwynne J (2010) Reading on grade level in third grade: How is it related to high school performance and college enrollment. Chicago, IL: Chapin Hall at the University of Chicago.

- Blum R (2017) Social Determinants of Adolescent Health.

- Chiu MM, Yin Chow BW (2010) Culture, motivation, and reading achievement: High school students in 41 countries. Elsevier 20: 579-592.

- Li Grining CP, Raver CC, Jones Lewis D, Madison Boyd S, Lennon J (2014) Targeting Classrooms' Emotional Climate and Preschoolers' Socioemotional Adjustment: Implementation of the Chicago School Readiness Project. Journal of prevention & intervention in the community 42(4): 264-281.

- Cloney D, Cleveland G, Hattie J, Collette T (2016) Variations in the Availability of Quality Early Childhood Education and Care by Socioeconomic Status of Neighborhoods. Early Education and Development 27(3): 384-401.

- Bradley R, Corwyn R (2002) Socioeconomic status and child development. Annual Review of Psychology 53: 371-399.

- Celano D, Neuman SB (2008) When schools close, the knowledge gap grows. Phi Delta Kappan 90(4): 256-262.

- Blair C, Ursache A, Greenberg M, Vernon Feagans L (2015) Multiple aspects of self-regulation uniquely predict mathematics but not letter-word knowledge in the early elementary grades. Developmental psychology 51(4): 459.

- Palermo F, Hanish LD, Martin CL, Fabes RA, Reiser M (2007) Preschoolers’ academic readiness: What role does the teacher–child relationship play? Early Childhood Research Quarterly 22(4): 407-422.

- Ziol Guest KM, McKenna CC (2014) Early childhood housing instability and school readiness. Child development 85(1): 103-113.

- Bernier A, Carlson S, Whipple N (2010) From external regulation to self- regulation: Early parenting precursors of young children's executive functioning. Society for Research in Child Development 81(1): 326-339.

- Clincy AR, Mills Koonce WR (2013) Trajectories of Intrusive Parenting During Infancy and Toddlerhood as Predictors of Rural, Low‐Income African American Boys' School‐Related Outcomes. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 83(2pt3): 194-206.

- McClelland MM, Cameron CE (2011) Self‐regulation and academic achievement in elementary school children. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development 2011(133): 29-44.

- Sohr Preston SL, Scaramella LV, Martin MJ, Neppl TK, Ontai L, et al. (2013) Parental socioeconomic status, communication, and children's vocabulary development: A third‐generation test of the family investment model. Child development 84(3): 1046-1062.

- Piccolo LdR, Salles JFd, Falceto OG, Fernandes CL, Grassi Oliveira R (2016) Can reactivity to stress and family environment explain memory and executive function performance in early and middle childhood? TRENDS in psychiatry and psychotherapy 38(2): 80-89.

- Martin A, Ryan RM, Brooks Gunn J (2010) When fathers’ supportiveness matters most: Maternal and paternal parenting and children’s school readiness. Journal of Family Psychology 24(2): 145.

- Stroustrup A, Hsu HH, Svensson K, Schnaas L, Cantoral A, et al. (2016) Toddler temperament and prenatal exposure to lead and maternal depression. Environmental Health 15(1): 71.

- Leve LD, Neiderhiser JM, Shaw DS, Ganiban J, Natsuaki MN, et al. (2013) The Early Growth and Development Study: a prospective adoption study from birth through middle childhood. Twin Research and Human Genetics, 16(1): 412-423.

- O Leary CM, Taylor C, Zubrick SR, Kurinczuk JJ, Bower C (2013) Prenatal alcohol exposure and educational achievement in children aged 8-9 years. Pediatrics, peds 132(2): e468-e475.

- Zhang N, Baker HW, Tufts M, Raymond RE, Salihu H, et al. (2013) Early childhood lead exposure and academic achievement: evidence from Detroit public schools, 2008–2010. American journal of public health 103(3): e72-e77.

- Richards JL, Chapple McGruder T, Williams BL, Kramer MR (2015) Does neighborhood deprivation modify the effect of preterm birth on children's first grade academic performance? Social Science & Medicine 132: 122-131.

- Adams Chapman I, Bann C, Carter SL, Stoll BJ, Network NNR (2015) Language outcomes among ELBW infants in early childhood. Early human development 91(6): 373-379.

- Duff FJ, Reen G, Plunkett K, Nation K (2015) Do infant vocabulary skills predict school‐age language and literacy outcomes? Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 56(8): 848-856.

- Connor CM, Ponitz CC, Phillips BM, Travis QM, Glasney S, et al. (2010) First graders' literacy and self-regulation gains: The effect of individualizing student instruction. Journal of School Psychology, 48(5): 433-455.

- Ursache A, Blair C, Raver CC (2012) The promotion of self‐regulation as a means of enhancing school readiness and early achievement in children at risk for school failure. Child Development Perspectives 6(2): 122-128.

- Zhai F, Brooks Gunn J, Waldfogel J (2011) Head Start and urban children's school readiness: a birth cohort study in 18 cities. Developmental psychology 47(1): 134.

- Skibbe LE, Connor CM, Morrison FJ, Jewkes AM (2011) Schooling effects on preschoolers’ self-regulation, early literacy, and language growth. Early Childhood Research Quarterly 26(1): 42-49.

- (2021) American Association for the Advancement of Science.

-

Danielle Gilmore. Reading at Grade Level by Third Grade: A Multi-Level Life Course Framework . Curr Tr Clin & Med Sci. 3(1): 2022. CTCMS.MS.ID.000555.

-

Influences, Symptoms, Critical influences, Mental health, Family environment, Depressed

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.