Research article

Research article

Prevalence of Reduced Kidney Function, Kidney Function Decline and Related Risk Factors among A Primary Care Population in China: A Repeated Cross-Sectional Study

Hongxia Shen1, Chong Chen1, and Xinwei Chang2*

1Guangzhou Medical University, Guangzhou, China

2Sun Yat-Sen Memorial Hospital, Sun Yat-Sen University, Guangzhou, China

Xinwei Chang, MD, PhD, Sun Yat-Sen Memorial Hospital, Sun Yat-Sen University, 107 Yanjiang West Road, Guangzhou, China

Received Date: May 24, 2025; Published Date: June 20, 2025

Abstract

Purpose: To explore the prevalence of reduced kidney function, kidney function decline and related risk factors for a primary health care

population in China.

Methods: We conducted a repeated cross-sectional study of 69473 adults who underwent routine health check-ups between 2004-2020 in

three primary health care centers in Zhengzhou city in China. Participant’s demographic and clinical information were collected. Reduced kidney

function was defined as an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) of <60 ml/min per 1.73 m2. Kidney function decline was defined as a drop

in the GFR category accompanied by a ≥25% drop in eGFR from baseline, or a sustained decline in eGFR of >5 ml/min per 1.73 m2/y. Rapid eGFR

decline was defined as a decline in eGFR of greater than 3 ml/min/1.73m2/y.

Results: A total of 18273 participants were enrolled in this study. Of whom, 3273(17.9%) had reduced kidney function at first measurement.

Follow-up serum creatinine was available for 3314 participants, with a mean follow-up duration of 1.5 years. During follow-up, 640 participants

(19.3%) experienced kidney function decline, and 755 (22.8%) showed rapid eGFR decline. Multivariable logistic regression analysis showed that

female sex, older age, hypertension, overweight, obesity, diabetes, left ventricular hypertrophy, and dyslipidemia were independent predictors of

reduced kidney function. In addition, older age and a reduced kidney function at baseline were independent predictors of kidney function decline.

Conclusion: Female sex, older age, hypertension, overweight, obesity, diabetes, LVH and dyslipidemia were independent predictors of reduced

kidney function. Effective three-level prevention and treatment strategies seem warranted to reduce the burden of chronic kidney disease in China.

Keywords: Chronic kidney disease; glomerular filtration rate; diabetes; obesity

Introduction

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is a major public health concern [1-3]. Globally, 698 million individuals are affected by CKD [4]. Also, CKD is associated with adverse outcomes including kidney failure, accelerated cardiovascular disease (CVD) and premature death [5,6]. In specific, a recent study reported that globally, 1.4 million CVDrelated deaths and 25.3 million CVD disability-adjusted life years are attributable to impaired kidney function [4]. The burden of CKD is particularly high in low-income and middle-income countries [7], including China, with an estimated prevalence of 10.8% (120 million adults) [8]. To reduce this burden, the identification of potentially modifiable risk factors for reduced kidney function [9] is essential to enable the prevention of CKD progression in an early stage. Previous evidence indicates that diabetes, hypertension and dyslipidemia can play an important role in the development of reduced kidney function [10-12]. Also, minimal, moderate, or rapid rates of estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) decline can predict premature mortality [13-16]. Some of the previous studies reported CKD progression and related risk factors [11,17], yet only a few studies reported on prevalence of reduced kidney function and related CVD risk factors for the Chinese population [18-20].

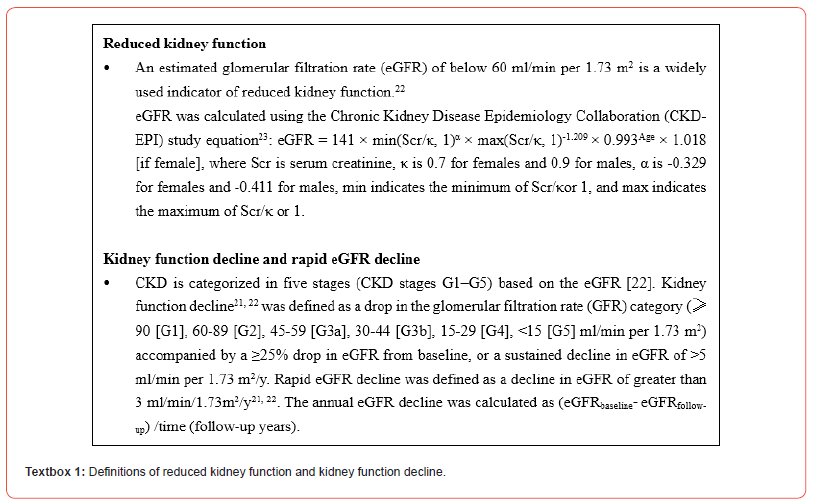

Also, none of these studies explored the prevalence of kidney function decline and related CVD risk factors, especially in Chinese primary care settings. Related definitions of reduced kidney function and kidney function decline are operationalized based on previous literature [21,22] and further detailed in Textbox 1. Better insights into the prevalence of reduced kidney function and kidney function decline in the Chinese primary care population is of vital importance to assess the burden of CKD in Chinese settings. Evidence on the burden of CKD can adequately inform public health policymakers, healthcare professionals, and community members on the impact of CKD. Also, identifying (modifiable) risk factors for reduced kidney function and kidney function decline has practical relevance to developing target effective strategies. Therefore, we performed a repeated cross-sectional study to examine the prevalence of reduced kidney function and kidney function decline and explore related risk factors in China.

Participants

We performed a repeated cross-sectional study and

accumulated data of routine health check-ups in a large primary

care population between 2004-2020 in three primary health care

centers in Zhengzhou City. Zhengzhou, the capital city of one of

the biggest provinces in China (Henan), has a population of over

10 million. Participants could receive health check-up for several

reasons:

a) If they were enrolled in the general practitioner-centered

primary care system in the primary health centers at the first

time, they had one free health check-up.

b) If they were aged 65 years or older, they had one free

annual health check-up.

c) Some people voluntarily received a health check-up when

they paid for it.

We followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement [24] to report our study. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Guangzhou Medical University (reference number L202212020).

Measurements

The health check-up results were entered into patient health care records by the patients’ physicians. The health check-up data include information on demographic characteristics (age, sex), physical examination parameters (height, weight, body temperature, pulse, breathing rate, body mass index and blood pressure), laboratory tests findings (fasting blood glucose, liver function, kidney function and the blood lipids), electrocardiogram (ECG) results and specific diagnoses made by the physicians (e.g. diagnosis of hypertension). No urine tests were performed. An anonymized database including electronic records was available for analysis. For our study, we extracted data on age, sex, body mass index (BMI), blood pressure (BP), fasting blood glucose, total cholesterol, fasting triglyceride, serum low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, serum highdensity lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, serum creatinine level, ECG test results and the diagnosis made by the physician.

Definitions

Definitions of reduced kidney function and kidney function decline are provided in Textbox 1. BMI was categorized into underweight (<18.5 kg/m2), healthy weight (18.5-23.9 kg/ m2), overweight (24-27.9 kg/m2) and obesity (≥28 kg/m2) by using the Chinese “Criteria of weight for adults (No. WS/T 428- 2013, available on http://www.nhfpc.gov.cn)”. Hypertension was defined as an average systolic BP (SBP)≥140mmHg or an average diastolic BP (DBP)≥90mmHg or a diagnosis of hypertension by a physician [25]. Diabetes was defined as a fasting blood glucose level of ≥7.00 mmol/l or a diagnosis of diabetes by a physician [10]. Dyslipidemia was defined as the presence of one or more abnormal serum lipid concentrations according to the Chinese guidelines for the prevention and treatment of dyslipidemia in adults [26]: total cholesterol>6.22 mmol/l; fasting triglycerides>2.26 mmol/l; LDL cholesterol>4.14 mmol/l; HDL cholesterol<1.04 mmol/l. Left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) was defined as an ECG-aided physician-diagnosis of LVH. The total number of CVD risk factors [10,27] per patient was calculated based on the presence of the following: obesity, hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia and LVH.

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using R (version 4.4.0). Descriptive analyses were performed, calculating the mean ± standard deviation (SD), median (interquartile range, IQR) and the proportions of categorical variables as appropriate. Continuous variables were compared using t-tests. Categorical variables were compared using Chi-square and Fisher’s exact tests, as appropriate. In the database of electronic records of 18273 adults, data were missing for SBP (0. 1%), DBP (0.1%), BMI (0.3%), fasting blood glucose (1.5%), total cholesterol (0.6%), fasting triglyceride (0.7%), serum LDL cholesterol (19.8%) and serum HDL cholesterol (19.9%). For the follow-up electronic records of 3314 out of the total 18273 participants, data were missing for SBP (0.3%), DBP (0.3%), BMI (0.4%), fasting blood glucose (1.6%), total cholesterol (0.4%), fasting triglyceride (0.5%), serum LDL cholesterol (42.6%) and serum HDL cholesterol (42.8%). Multiple data imputation was used to handle the missing data [28].

28 We compared multivariable logistic regression analyses results by using multivariable multiple imputations of 10 imputations and 20 imputations and similar results were found. Hence, we used multivariable multiple imputations with 10 imputations and assumed the data were completely missing at random. The univariable analyses were performed on the complete case data and the multivariable logistic regression analyses were performed on each imputed dataset. Univariable and multivariable logistic regression analyses were used to explore the association between reduced kidney function and potential risk factors. In the first model, we adjusted for sex and age (per year increase). In the second model, based on the results of univariable analyses and previous literature reporting risk factors of reduced kidney function [11,29], we additionally adjusted for hypertension (yes versus no), BMI (healthy weight [reference] versus underweight versus overweight versus obesity), diabetes (yes versus no), LVH (yes versus no), dyslipidemia (yes versus no) and the number of CVD risk factors (0 [reference] versus 1-2 versus ≥3).

Similarly, we used univariable and multivariable logistic regression analyses to examine the association between kidney function decline and potential risk factors. All tests were twosided with a significance level of P values<0.05. Also, to account for multiple testing, we used the Bonferroni correction and reported significant associations for which P < 0.05/number of comparisons in univariable analyses.

Results

Participant Characteristics

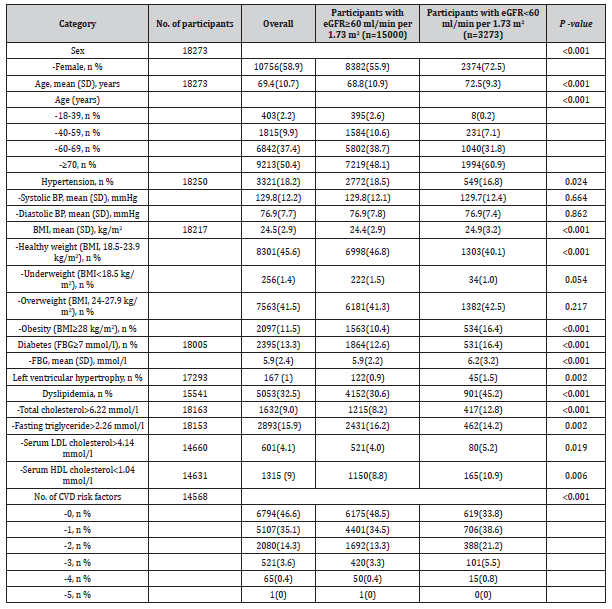

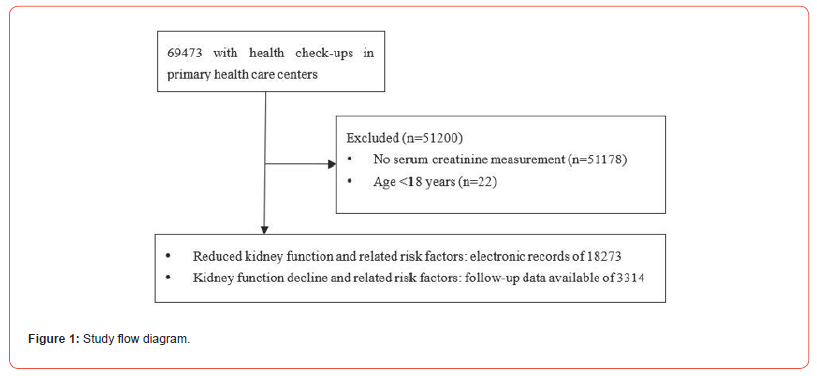

A total of 69473 residents underwent health check-ups between 2004-2020 in three primary health care centers. Serum creatinine was measured for 18295 residents; electronic records were included of all residents aged ≥ 18 years old for 18273 participants. Using the creatinine measurements, we calculated the eGFR using the CKD-EPI study equation [23]. Follow-up data of serum creatinine measurement was available for 3314 participants (18%), with a mean follow-up duration of 1.5 years (study flow diagram in Figure 1). Participant characteristics are shown in Tables 1&2. Of all participants, 9213 (50.4 %) were aged ≥70 years and 10756 (58.9%) were female. The mean eGFR from the first measurement was 81.56±25.73 ml/min/1.73m2.

Table 1:Participants characteristics and related prevalence of reduced kidney function.

eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; BP, blood pressure; BMI, body mass index; FBG, fasting blood-glucose; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; CVD, cardiovascular disease.

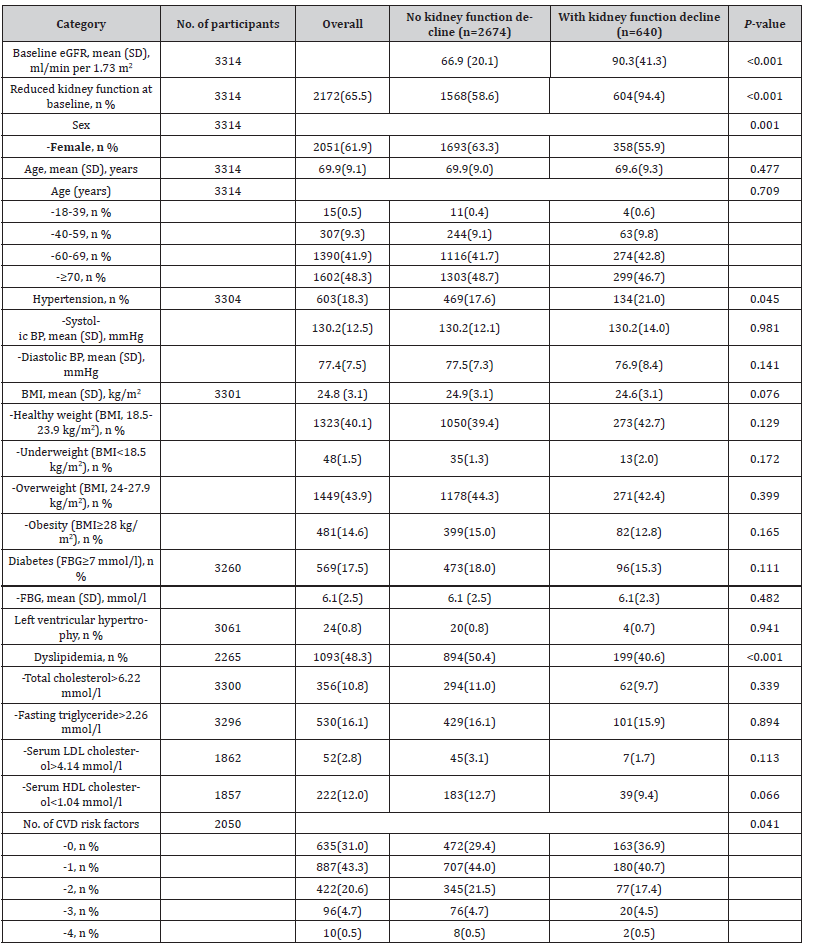

Table 2:Participants characteristics and related presence of kidney function decline.

eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; BP, blood pressure; BMI, body mass index; FBG, fasting blood-glucose; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; CVD, cardiovascular disease.

Prevalence of Reduced Kidney Function and Kidney Function Decline

Of all participants, 3273 (17.9%) had reduced kidney function at first measurement. For people aged ≥60 years old, 3034 (18.8%) had reduced kidney function vs. 239 (10.7%) for people <60 years old (Table 1). Of the participants with a follow-up, 640 (19.3%) had kidney function decline and 755 (22.8%) had rapid eGFR decline (Table 2).

Factors Associated with Reduced Kidney Function

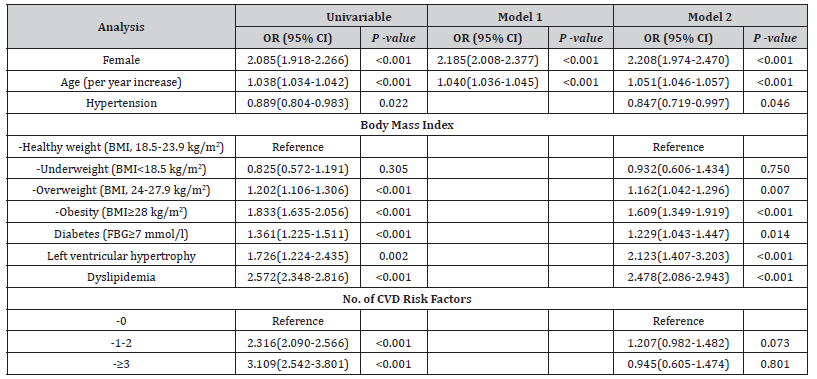

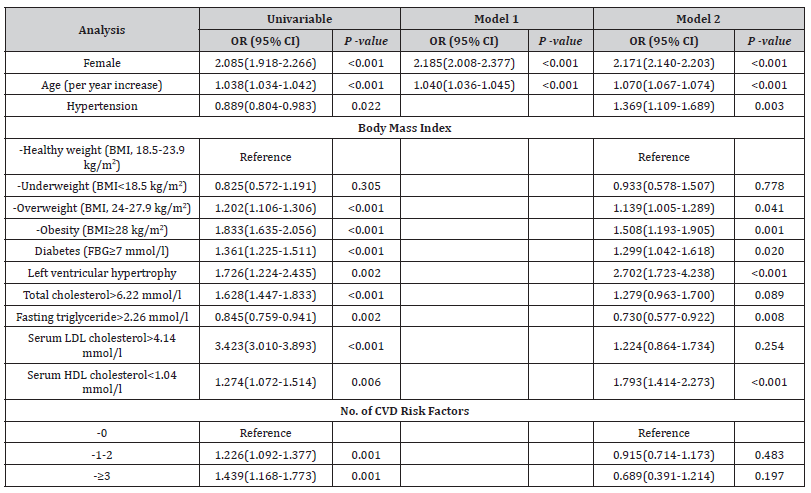

Table 1 shows that the following factors were associated with reduced kidney function: sex, age, hypertension, overweight, obesity, diabetes, LVH, dyslipidemia and the number of CVD risk factors. After applying the Bonferroni correction, hypertension was no longer significantly associated with reduced kidney function. Using univariable and multivariable logistic regression models, in the final model, female sex, older age, hypertension, overweight, obesity, diabetes, LVH and dyslipidemia were independent predictors of reduced kidney function (Table 3). When considering total cholesterol, triglycerides, LDL cholesterol, HDL cholesterol as separate risk factors, the multivariable logistic regression analysis showed that female sex, older age, hypertension, overweight, diabetes, LVH, fasting triglyceride>2.26 mmol/l and serum HDL cholesterol<1.04 mmol/l were independent predictors of reduced kidney function (Supplementary Table S1).

Table 3:Factors associated with reduced kidney function.

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; BMI, body mass index; FBG, fasting blood-glucose; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; CVD, cardiovascular disease. Model 1 was adjusted for sex and age; Model 2 adjusted for sex, age, hypertension, body mass index, diabetes and left ventricular hypertrophy, dyslipidemia and no. of CVD risk factors.

Supplementary Table S1:Factors associated with reduced kidney function.

The total number of CVD risk factors per patient was calculated based on the presence of the following: obesity, hypertension, diabetes, abnormal total cholesterol, abnormal fasting triglycerides, abnormal LDL cholesterol, abnormal LDL cholesterol and LVH. OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval;BMI, body mass index; FBG, fasting blood-glucose; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; CVD, cardiovascular disease. Model 1 was adjusted for sex and age; Model 2 adjusted for sex, age, hypertension, body mass index, diabetes and left ventricular hypertrophy, total cholesterol> 6.22 mmol/l, fasting triglyceride>2.26 mmol/l, serum LDL cholesterol>4.14 mmol/l, serum HDL cholesterol<1.04 mmol/l and no. of CVD risk factors.

Factors Associated with Kidney Function Decline

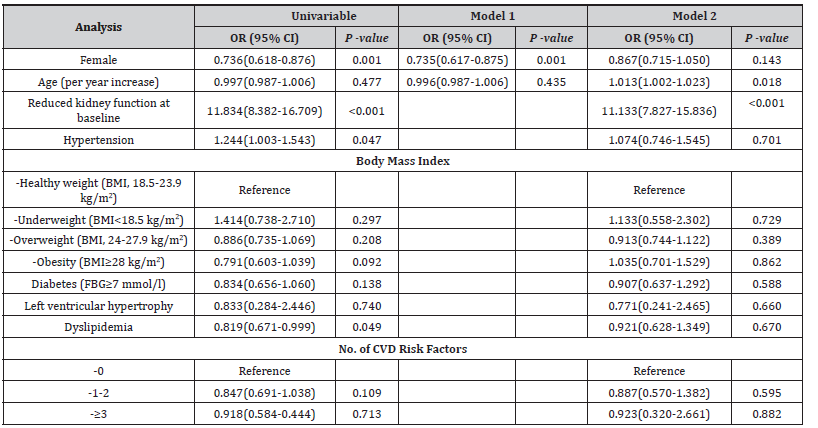

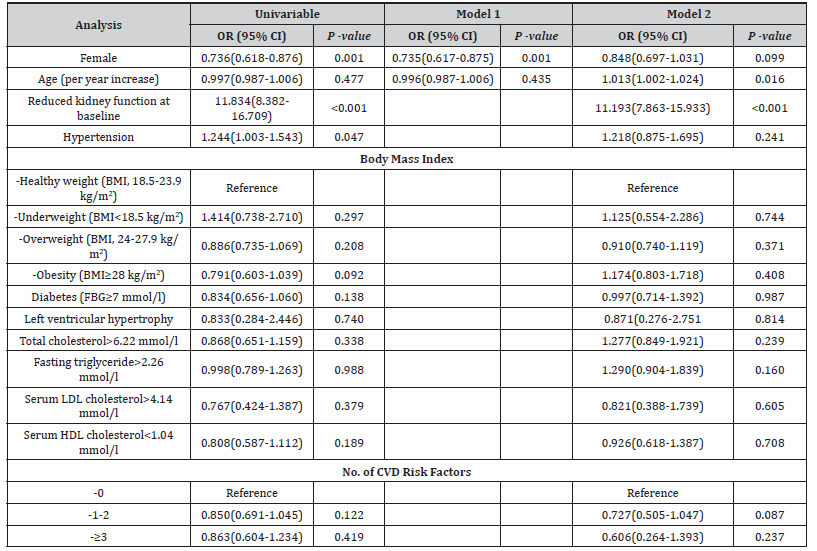

Table 2 shows that the following factors were associated with kidney function decline: a reduced kidney function at baseline, sex, hypertension, dyslipidemia and the number of CVD risk factors. After applying the Bonferroni correction, hypertension and the number of CVD risk factors were no longer significantly associated with kidney function decline. Using univariable and multivariable logistic regression models, in the final model, older age and a reduced kidney function at baseline were independent predictors of kidney function decline (Table 4). When considering total cholesterol, triglycerides, LDL cholesterol, HDL cholesterol as separate risk factors, the multivariable logistic regression analysis showed that older age and a reduced kidney function at baseline were independent predictors of kidney function decline (Supplementary Table S2).

Table 4:Factors associated with kidney function decline.

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; BMI, body mass index; FBG, fasting blood-glucose; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; HDL, high-density lipoprotein;CVD, cardiovascular disease. Model 1 was adjusted for sex and age; Model 2 adjusted for sex, age, hypertension, body mass index, diabetes and left ventricular hypertrophy, dyslipidemia and no. of CVD risk factors.

Supplementary Table S2:Factors associated with kidney function decline.

The total number of CVD risk factors per patient was calculated based on the presence of the following: obesity, hypertension, diabetes, abnormal total cholesterol, abnormal fasting triglycerides, abnormal LDL cholesterol, abnormal LDL cholesterol and LVH. OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; BMI, body mass index; FBG, fasting blood-glucose; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; CVD, cardiovascular disease. Model 1 was adjusted for sex and age; Model 2 adjusted for sex, age, hypertension, body mass index, diabetes and left ventricular hypertrophy, total cholesterol> 6.22 mmol/l, fasting triglyceride>2.26 mmol/l, serum LDL cholesterol>4.14 mmol/l, serum HDL cholesterol<1.04 mmol/l and no. of CVD risk factors.

Discussion

This study explored the prevalence of reduced kidney function and kidney function decline in a large, urban Chinese primary care population. Results revealed a prevalence of reduced kidney function of 17.9% and a prevalence of kidney function decline of 19.3%. The prevalence of rapid eGFR decline was 22.8%. Female sex, older age, hypertension, overweight, obesity, diabetes, LVH and dyslipidemia were independent predictors of reduced kidney function. Moreover, older age and a reduced kidney function at baseline were independent predictors of kidney function decline.

Prevalence of Reduced Kidney Function and Kidney Function Decline

The prevalence of reduced kidney function that we found was similar to the 12-23% reported in previous studies in the elderly Chinese population based on health check-up data [18-20]. Our study population was relatively old (69.4±10.7 years). For other countries, the prevalence of reduced kidney function in older people was reported to be 37.1% to 61.7% (Germany; age>70 years old) [30], 19.6% (Brazil; aged ≥60 years) [31] and 11.2% (Australia; mean age of 62 years old) [32]. These discrepancies found may partially be explained by differences in the equations to estimate GFR [30], characteristics of the populations and the setting. Our study was conducted in a primary care setting, while other studies were conducted in community settings; patients could suffer from a chronic illness. This could also explain why we found a higher prevalence of kidney function decline and rapid eGFR decline compared to a previous Chinese community-based population study reporting normal kidney function at baseline [21].

Additionally, the prevalence of rapid eGFR decline in our study was higher than the reported 16% in a community-based cohort of ambulatory elderly individuals in the United States [33]. This could also be explained by the fact that we included data of both participants with and without reduced kidney function at baseline; people with reduced kidney function at baseline would more likely have kidney function decline. Also, the disparity in quality of and access to health care between areas in China could lead to the higher prevalence of kidney function decline in our study. For instance, the previous study was conducted in Beijing with better health care resources than our study setting [21].

Factors Associated with Reduced Kidney Function and Kidney Function Decline

We found that diabetes was independently associated with reduced kidney function, which is consistent with a previous study [34]. The Global Burden of Disease study suggested that diabetes affects 6.6% of the overall (all-age) Chinese population [35]. Moreover, LVH was revealed as a risk factor for reduced kidney function, which corroborates previous findings [10]. Notably, hypertension, which is a key risk factor of LVH [36], was associated with a lower risk of reduced kidney function in the current study. This could be explained by the use of antihypertensive medications in patients with reduced kidney function in our population. People with reduced kidney function may have been undertreated for CKD and also already treated for hypertension. In the past twenty years, a noteworthy increase in the prevalence of hypertension in the Chinese population has occurred; hypertension affects nearly 23.2% of Chinese adults [37]. Future studies with information on participants’ medication use are needed to explore this question further.

Female sex was shown as a risk factor for reduced kidney function, which corroborates previous findings [8]. However, in contrast, other studies indicated that being male is an independent risk factor for reduced kidney function [38]. Future studies can clarify the association between gender difference and reduced kidney function by considering lifestyle differences, such as dietary protein intake, salt, smoking and alcohol intake [39]. Additionally, overweight and obesity were associated with an increased risk of reduced kidney function in our study. Previous data also linked overweight and obesity to reduced kidney function [34,40] and CKD progression [41]. Overweight and obesity are widely prevalent and are major public health concerns [42,43]. Previous studies suggested that dyslipidemia mostly develops along with kidney function decline in patients with CKD, even in the early stages. It is also the major risk factor for CVD in patients with CKD [44].

In our study, the prevalence of dyslipidemia was 32.5%, which is similar to a previous survey [40]. We also demonstrated that dyslipidemia was associated with reduced kidney function. Thompson et al. found that reduced kidney function was independently associated with lower concentrations of HDL cholesterol and higher concentrations of triglycerides in an Australian population [29]. Similarly, in our study, the proportion of low HDL cholesterol was higher in participants with reduced kidney function than in participants without reduced kidney function. However, the proportion of high fasting triglyceride was lower in participants with reduced kidney function than in participants without reduced kidney function. This could be explained by the use of anti-dyslipidemia medications in patients with reduced kidney function in our population. Nevertheless, the high proportion of high fasting triglyceride still deserves medical attention due to its notable consequences.

Strengths and Limitations

Our study has several strengths. To our knowledge, this study is the first primary care population-based study in China to examine the prevalence of kidney function decline and rapid eGFR decline. Also, our study has a large sample size and conducts analyses based on real-world data. Nevertheless, several limitations should be noted. First, as our study focused on people with health check-up records, information concerning urine tests (e.g. data of albuminuria), the usage of medications such as anti-hypertensive, anti-diabetic and anti-dyslipidemia drugs, self-reported history such as smoking and alcohol use of people and socioeconomic status were not available. Secondly, as participants aged 65 years or older had one free annual health check-up, the entire study population was relatively old. Therefore, the prevalence of reduced kidney function and kidney function decline can be overestimated. Also, these findings may not generalize to the younger population.

Third, the serum creatinine measurement was available for 18273 (26.3%) of 69473 people and the follow-up data were available for 3314 (18%) of 18273 people. The related reasons for the lack of data were unknown and could influence the results. For instance, patients with more severe kidney impairment may go for health check-ups more frequently. A prospective cohort study can be conducted for further exploration.

Implications for Future Research Initiatives

To reduce the substantial burden of CKD in the Chinese primary care population, an effective prevention and treatment health care system is needed. For instance, three-level prevention and treatment programs are being developed in Chinese settings [45]. These programs often include primary prevention and treatment, which focuses on targeted screening to achieve early detection of CKD in at-risk groups (e.g. people with diabetes); secondary prevention and treatment, which focuses on the referral of those identified as pre-existing CKD to community hospitals and aims to slow disease progression; tertiary prevention and treatment, which aims to avoid or delay dialysis or kidney transplantation for patients with advanced CKD. To enhance the development of threelevel prevention and treatment system in Chinese settings, we suggest the following initiatives. First, we advise future researchers to implement (online) training and education such as e-learning on CKD prevention and treatment to increase public and health care professional awareness about CKD and its risk factors.

Also, considering the risk factors of reduced kidney function are mostly related to lifestyle-related factors such as overweight, lifestyle interventions are needed to support individuals’ selfmanagement and improve their health behaviors. As there is an enormous shortage of healthcare professionals in China [46], electronic health (eHealth)-based lifestyle interventions are more accessible and widely used [47]. Second, to support the referral of patients with kidney impairment to a nephrologist in a secondary or tertiary hospital, national guidelines should be developed for medical specialists such as the referral criteria adopted in the Netherlands [48]. Also, an improved primary healthcare system supporting the implementation of integrated approaches can help manage the increasing burden of CKD [49], for instance, the Innovative Care for Chronic Conditions (ICCC) proposed by the World Health Organization (WHO) [50].

Conclusion

In conclusion, the high prevalence of reduced kidney function and kidney function decline indicates that CKD is a severe public health problem in China. Female sex, older age, hypertension, overweight, obesity, diabetes, LVH and dyslipidemia were independent predictors of reduced kidney function, and older age, a reduced kidney function at baseline to kidney function decline. To reduce the substantial CVD risk and CKD burden in Chinese primary care populations, three-level preventive and treatment programs need to be developed and enhanced. Important strategies would include an (online) education and training program to promote awareness of CKD, widely and accessible (eHealth-based) lifestyle interventions, national guidelines for referral of identified patients to a nephrologist and improving the primary healthcare systems to support the implementation of integrated approaches.

Author Contributions

HS and XC contributed to the study conception and design. HS, XC collected the data and carried out the analysis. The first draft of the manuscript was written by HS, XC, and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. The paper has been read and approved by all authors.

Declarations

All the authors declared no competing interests.

Funding

This work was supported by the Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (grant numbers 2022A1515110351).

Data availability

All relevant data during this study are within the paper.

References

- Webster AC, Nagler EV, Morton RL, Masson P (2017) Chronic Kidney Disease. Lancet 389: 1238-1252.

- Chesnaye NC, Ortiz A, Zoccali C, Stel VS, Jager KJ (2024) The impact of population ageing on the burden of chronic kidney disease. Nat Rev Nephrol 20(9): 569-585.

- Kovesdy CP (2022) Epidemiology of chronic kidney disease: an update 2022. Kidney Int Suppl 12(1): 7-11.

- GBD Chronic Kidney Disease Collaboration (2020) Global, regional, and national burden of chronic kidney disease, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 395(10225): 709-733.

- Flythe JE, Watnick S (2024) Dialysis for Chronic Kidney Failure: A Review. JAMA 332(18): 1559-1573.

- Smith PA, Sarris I, Clark K, Wiles K, Bramham K (2025) Kidney disease and reproductive health. Nat Rev Nephrol 21(2): 127-143.

- Chen SH, Tsai YF, Sun CY, Lee CC, Wu MS (2011) The impact of self-management support on the progression of chronic kidney disease--a prospective randomized controlled trial. Nephrol Dial Transplant 26(11): 3560-3566.

- Zhang L, Wang F, Wang L, Wang W, Liu B, et al. (2012) Prevalence of chronic kidney disease in China: a cross-sectional survey. Lancet 379(9818): 815-822.

- Stevens LA, Levey AS (2005) Measurement of kidney function. Med Clin North Am 89(3): 457-473.

- Shlipak MG, Fried LF, Cushman M, Manolio TA, Peterson D, et al. (2005) Cardiovascular mortality risk in chronic kidney disease: comparison of traditional and novel risk factors. Jama 293(14): 1737-1745.

- Jafar TH, Islam M, Jessani S, Bux R, Inker LA, et al. (2011) Level and determinants of kidney function in a South Asian population in Pakistan. Am J Kidney Dis 58(5): 764-772.

- Middleton JP, Pun PH (2010) Hypertension, chronic kidney disease, and the development of cardiovascular risk: a joint primacy. Kidney Int 77(9): 753-755.

- Coresh J, Turin TC, Matsushita K, Sang Y, Ballew SH, et al. (2014) Decline in estimated glomerular filtration rate and subsequent risk of end-stage renal disease and mortality. Jama 311(24): 2518-2531.

- Krolewski AS (2015) Progressive renal decline: the new paradigm of diabetic nephropathy in type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 38(6): 954-962.

- Krolewski AS, Niewczas MA, Skupien J, Gohda T, Smiles A, et al. (2014) Early progressive renal decline precedes the onset of microalbuminuria and its progression to macroalbuminuria. Diabetes Care 37(1): 226-234.

- Grams ME, Sang Y, Ballew SH, Carrero JJ, Djurdjev O, et al. (2018) Predicting timing of clinical outcomes in patients with chronic kidney disease and severely decreased glomerular filtration rate. Kidney Int 93(6): 1442-1451.

- Young BA, Katz R, Boulware LE, Kestenbaum B, Boer IHD, et al. (2016) Risk Factors for Rapid Kidney Function Decline Among African Americans: The Jackson Heart Study (JHS). Am J Kidney Dis 68(2): 229-239.

- Chen JF, Li Y (2017) Estimated glomerular filtration rate and the affecting factors in urban and rural elderly in Pudong district of Shanghai. Chinese Journal of General Practice 15: 823-826.

- Xu RH, Peng LR, Xu YY (2019) Analysis on the screening assessment and complications of chronic kidney disease of elderly residents in Dongjing community of Songjiang District, Shanghai. J Pub Health Prev Med 30: 90-94.

- Yang YL, Zou HQ, Wang YW (2013) Comparison of two equations for calculating glomerular filtration rate in evaluation of the prevalence of chronic kidney disease in healthy population. J South Med Univ 33: 1347-1351.

- Fan F, Qi L, Jia J, Xu X, Lui Y, et al. (2016) Noninvasive Central Systolic Blood Pressure Is More Strongly Related to Kidney Function Decline Than Peripheral Systolic Blood Pressure in a Chinese Community-Based Population. Hypertension 67(6): 1166-1172.

- Eknoyan G, Lameire N, Eckardt K (2013) KDIGO 2012 clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int 3: 5-14.

- Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, Zhang LZ, Castro AF, et al. (2009) A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med 150(9): 604-612.

- Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M (2008) The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. J Clin Epidemiol 261: 344-349.

- Foley RN, Wang C, Collins AJ (2005) Cardiovascular risk factor profiles and kidney function stage in the US general population: the NHANES III study. Mayo Clin Proc 80(10): 1270-1277.

- Joint Committee for Developing Chinese guidelines on Prevention and Treatment of Dyslipidemia in Adults (2007) Chinese guidelines on prevention and treatment of dyslipidemia in adults. Chinese Journal of Cardiology 35(5): 390-419.

- Zoccali C (2006) Traditional and emerging cardiovascular and renal risk factors: an epidemiologic perspective. Kidney Int 70(1): 26-33.

- Goeij MC, van Diepen M, Jager KJ, Tripepi G, Zoccali C, et al. (2013) Multiple imputation: dealing with missing data. Nephrol Dial Transplant 28(10): 2415-2420.

- Thompson M, Ray U, Yu R, Hudspeth A, Smillieet M, et al. (2016) Kidney Function as a Determinant of HDL and Triglyceride Concentrations in the Australian Population. J Clin Med 5(3): 35.

- Ebert N, Jakob O, Gaedeke J, der Giet MV, Kuhlmann MK, et al. (2017) Prevalence of reduced kidney function and albuminuria in older adults: the Berlin Initiative Study. Nephrol Dial Transplant 32(6): 997-1005.

- Abdulkader R, Burdmann EA, Lebrão ML, Duarteet YAO, Zanetta DMT (2017) Aging and decreased glomerular filtration rate: An elderly population-based study. PLoS One 12(12): e0189935.

- Chadban SJ, Briganti EM, Kerr PG, Dunstan DW, Welborn TA, et al. (2003) Prevalence of kidney damage in Australian adults: The AusDiab kidney study. J Am Soc Nephrol 14(7 Suppl 2): S131-138.

- Shlipak MG, Katz R, Kestenbaum B, Friedet LF, Newman AB, al. (2009) Rate of kidney function decline in older adults: a comparison using creatinine and cystatin C. Am J Nephrol 30(3): 171-178.

- Duan J-Y, Duan G-C, Wang C-J, Liu D-W, Qiao Y-J, et al. (2020) Prevalence and risk factors of chronic kidney disease and diabetic kidney disease in a central Chinese urban population: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Nephrol 21(1): 115.

- Liu M, Liu SW, Wang LJ, Bai YM, Zeng XY, et al. (2019) Burden of diabetes, hyperglycaemia in China from to 2016: Findings from the 1990 to 2016, global burden of disease study. Diabetes Metab 45(3): 286-293.

- Aronow WS (2017) Hypertension and left ventricular hypertrophy. Ann Transl Med 5(15): 310.

- Wang Z, Chen Z, Zhang L, Wang X, Hao G, et al. (2018) Status of Hypertension in China: Results From the China Hypertension Survey, 2012-2015. Circulation 137(22): 2344-2356.

- Hallan SI, Dahl K, Oien CM, Aasberg A, Holmen J, et al. (2006) Screening strategies for chronic kidney disease in the general population: follow-up of cross sectional health survey. BMJ 333(7577): 1047.

- Iseki K (2008) Gender differences in chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int 74(4): 415-417.

- Duan J, Wang C, Liu D, Qiao Y, Pan S, et al. (2019) Prevalence and risk factors of chronic kidney disease and diabetic kidney disease in Chinese rural residents: a cross-sectional survey. Sci Rep 9(1): 10408.

- Grubbs V, Lin F, Vittinghoff E, Shlipak MG, Peralta CA, et al. (2014) Body mass index and early kidney function decline in young adults: a longitudinal analysis of the CARDIA (Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults) study. Am J Kidney Dis 63(4): 590-597.

- Liu X, Wu W, Mao Z, Huo W, Tu R, et al. (2018) Prevalence and influencing factors of overweight and obesity in a Chinese rural population: the Henan Rural Cohort Study. Sci Rep 8(1): 13101.

- Ortega FB, Lavie CJ, Blair SN (2016) Obesity and Cardiovascular Disease. Circ Res 118(11): 1752-1770.

- Hager MR, Narla AD, Tannock LR (2017) Dyslipidemia in patients with chronic kidney disease. Rev Endocr Metab Disord 18(1): 29-40.

- Wang JS, Shi JT, Xu B (2018) Advantages and significance of a three-level prevention and treatment system for chronic kidney disease in Shanghai. Academic Journal of Second Military Medical University 39: 24-28.

- Wu Q, Zhao L, Ye XC (2016) Shortage of healthcare professionals in China. BMJ 354: i4860.

- Shen H, van der Kleij R, van der Boog PJM, Chang X, Chavannes NH (2019) Electronic Health Self-Management Interventions for Patients With Chronic Kidney Disease: Systematic Review of Quantitative and Qualitative Evidence. J Med Internet Res 21(11): e12384.

- Meijer LJ, Schellevis F (2012) Referring patients with chronic renal failure: differences in referral criteria between hospitals. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd 156(50): A5259.

- Ameh OI, Ekrikpo U, Bello A, Okpechi I (2020) Current Management Strategies of Chronic Kidney Disease in Resource-Limited Countries. Int J Nephrol Renovasc Dis 13: 239-251.

- Alkenizan A (2004) Innovative care for chronic conditions: building blocks for action. Annals of Saudi Medicine 24: 148.

-

Hongxia Shen, Chong Chen, and Xinwei Chang*. Prevalence of Reduced Kidney Function, Kidney Function Decline and Related Risk Factors among A Primary Care Population in China: A Repeated Cross-Sectional Study. Curr Tr Clin & Med Sci. 4(2): 2025. CTCMS.MS.ID.000583.

-

Chronic kidney disease; glomerular filtration rate; diabetes; obesity; iris publishers; iris publisher’s group

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.