Research Article

Research Article

Effect and Route of Preoperative Biliary Drainage in Patients with Resectable Perihilar Cholangiocarcinoma: A Systematic Review of Systematic Reviews

Xinwei Chang1*, Hongxia Shen2, Frank G. Schaap3,4, Maxime J.L. Dewulf5, Bas Groot Koerkamp6, Christiaan van der Leij7, Ulf P. Neumann4,5, Jos Kleijnen8, and Steven W.M. Olde Damink3,4,5

1Breast Tumor Center, Sun Yat-Sen Memorial Hospital, Sun Yat-Sen University, Guangzhou, China

2School of Nursing, Guangzhou Medical University, Guangzhou, China

3Department of Surgery, NUTRIM School of Nutrition and Translational Research in Metabolism, Maastricht University, Maastricht 6229 ER, the Netherlands;

4Department of General, Visceral and Transplantation Surgery, RWTH University Hospital Aachen, Aachen 52074, Germany

5Department of Surgery, Maastricht University Medical Center, Maastricht 6229 HX, the Netherlands

6Department of Surgery, Erasmus MC Cancer Institute, University Medical Center Rotterdam, Rotterdam 3015 GD, the Netherlands

7Department of Radiology, Maastricht University Medical Center, Maastricht 6229 HX, the Netherlands

8School for Public Health and Primary Care (CAPHRI), Maastricht University, Maastricht 6200 MD, the Netherlands

Xinwei Chang, MD, PhD, Yat-Sen Memorial Hospital, Sun Yat-Sen University, 107 Yanjiang West Road, Guangzhou, China

Received Date:August 15, 2025; Published Date:August 28, 2025

Abstract

Purpose: The beneficial effect, and route of preoperative biliary drainage (BD) via percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage (PTBD) or

endoscopic biliary drainage (EBD), in resectable perihilar cholangiocarcinoma (pCCA) are heavily debated. The aim of this study is to assess the

quality of available systematic reviews (SRs) and clarify the effect and route of preoperative BD on perioperative and long-term outcomes in patients

with resectable pCCA.

Methods: PubMed, Embase, Cochrane Library, and KSR Evidence were searched from inception to February 28, 2025, to identify SRs with or

without meta-analysis. Risk of Bias in Systematic reviews (ROBIS) assessment tool was used.

Results: Eleven SRs with meta-analysis including 5950 patients were identified. All but one original studies in the SRs were retrospective and

at risk of bias. Ten of eleven SRs had high risk of bias. For preoperative BD versus no preoperative BD, all SRs showed no statistical differences in

postoperative mortality (odds ratios (ORs) from 0.70 to 1.06). Preoperative BD was associated with increased postoperative major morbidity in

‘simple criteria’ patients receiving BD only based on the presence of jaundice (OR 1.57 95% CI 1.10-2.25). For EBD versus PTBD, three of four SRs

showed that the postoperative mortality was not significantly different between two groups (ORs from 0.47 to 0.63). EBD was associated with higher

drainage-related overall morbidity, cholangitis and pancreatitis rates in three of four, three of five, and four of four SRs, respectively (ORs from 2.23

to 3.13, 4.58 to 5.41, 7.46 to 11.52, respectively). PTBD was associated with higher seeding metastasis rates and worse postoperative overall survival

(ORs from 0.35 to 0.46, hazard ratios (HR) 0.67 95% CI 0.53-0.85, respectively).

Conclusion: This study highlights that most available evidence on preoperative BD has high risk of bias and does not settle the debate on its role

or optimal approach. The preoperative BD may be best reserved for carefully selected patients, and EBD carries higher short-term drainage-related

morbidity but potentially better long-term oncological outcomes.

Keywords:Perihilar cholangiocarcinoma; biliary drainage; systematic reviews; effect; route; mortality

Abbreviations: BD: Biliary drainage; PTBD: Percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage; EBD: Endoscopic biliary drainage; pCCA: perihilar cholangiocarcinoma; SR: Systematic review; ROBIS: Risk Of Bias In Systematic reviews; EHC: Enterohepatic circulation; EBS: Endoscopic biliary stenting; ENBD: Endoscopic nasobiliary drainage; PRISMA: Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses; MeSH: Medical Subject Headings; RR: Relative risk; OR: Odds ratio; CI: Confidence interval; HR: Hazard ratios; FLR: Future liver remnant; RCT: Randomized controlled trial; FXR: farnesoid X receptor

Introduction

Perihilar cholangiocarcinoma (pCCA) is the most common type of bile duct malignancy, accounting for 50% to 60% of all cholangiocarcinoma cases [1,2]. Some 90% of patients with pCCA clinically present with (painless) obstructive jaundice [3]. Surgery with complete resection represents the only curative opportunity, with approximately 75% of patients eligible for surgical resection [4]. However, the prognosis of patients after surgery remains poor and 5-year survival rates are around 30% [5]. Moreover, liver resection in patients with hyperbilirubinemia and (resolved) cholangitis carries a high postoperative risk of severe complications and mortality [6]. Preoperative biliary drainage (BD) is employed to decompress the biliary tree, treat cholangitis, and improve (future remnant) liver function [7,8]. BD can be performed unilaterally or bilaterally, and principally drains the future liver remnant [9]. BD is performed via a percutaneous procedure (PTBD: percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage) or an endoscopic biliary drainage (EBD) procedure.

Studies have demonstrated that preoperative BD can reverse the cholestasis-associated pro-fibrotic and inflammatory status of the liver, and enhance the ability of the liver to regenerate [10,11]. However, the value of preoperative BD in resectable pCCA is under debate. Some studies argued against the utility of preoperative BD, finding no benefits in reducing postoperative complications and mortality [12-14]. Patients receiving preoperative BD even had higher mortality after left hemi-hepatectomy [10]. In addition, the optimal drainage route still needs to be determined. PTBD can lead to the diversion of bile, subsequent disturbed enterohepatic circulation (EHC), and impaired liver regeneration [9]. Also, PTBD can be complicated by seeding metastasis, affecting patients’ survival [15,16]. EBD, including endoscopic biliary stenting (EBS, internal) and endoscopic nasobiliary drainage (ENBD, external) modes, is considered less invasive and avoids the potential disadvantages of PTBD. However, EBD can result in cholangitis, as it creates a direct connection between the proximal intestine and the biliary system, a risk for postoperative death [8,17].

Several systematic reviews (SRs) [18-28] addressed the effects of preoperative BD versus no preoperative BD, as well as PTBD versus EBD on drainage-related and/or postoperative outcomes in patients with resectable pCCA. However, these reviews [18-28] reported inconsistent results on the same outcomes indicators. For example, two SRs [18,19] showed significantly higher overall postoperative morbidity in patients with preoperative BD. In contrast, two other SRs [20,21] found no significant difference in overall postoperative morbidity between drained and undrained patients. Moreover, the methodological quality of published SRs is undetermined, and risk of bias may exist. These limitations of previous SRs make it difficult for clinicians to decide whether or not to perform BD and which method to employ to minimize morbidity for patients with resectable pCCA. This review, therefore, aims to systematically study all SRs with available evidence to assess the effect of preoperative BD versus no preoperative BD, and the superiority of EBD versus PTBD on perioperative and long-term outcomes in patients with resectable pCCA. Particularly, we also aimed to evaluate the quality (risk of bias) of available SRs.

Materials and Methods

This study was reported in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement [29]. After a preliminary literature survey, the protocol was written and registered at the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) with registration number CRD42019141412.

Search Strategy

We used a combination of Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) and free-text terms to search PubMed, Embase (Ovid), Cochrane Library, and KSR Evidence (https://ksrevidence.com, it is a database that includes all systematic reviews and meta-analyses published since 2015) from inception until February 28, 2025. We also searched PROSPERO and ClinicalTrials.gov to identify any unpublished studies. The search strategy was developed in collaboration with a certified librarian and further refined by another experienced reviewer (JK) using the following conceptual groups: (1) biliary drainage, (2) perihilar cholangiocarcinoma, and (3) mortality/ survival (Appendix S1). No language restrictions were applied in any of the databases. We checked the references in included papers for further studies.

Study Selection

a) Two investigators (XC and HS) independently screened the

titles and abstracts and then full texts to identify eligible

studies for inclusion. Any disagreements were resolved by

discussion. We selected the most recent version in the case of

duplicate reports. We included studies which met the following

criteria: Studies included adult patients (≥18 years old) with

resectable pCCA.

b) Studies investigated whether or not to perform preoperative

BD or the effect of EBD compared with PTBD in pCCA.

c) Studies reported on at least one of these outcomes: drainagerelated

morbidity (e.g. cholangitis, pancreatitis, portal vein

injury, cancer seeding, and bleeding), postoperative morbidity

(e.g. liver failure, sepsis, and bile leakage), postoperative

mortality, survival.

d) Studies were SRs, with or without meta-analysis.

We excluded studies involving patients with obstructive jaundice not due to pCCA, such as autoimmune diseases (e.g. IgG4- related autoimmune cholangitis or primary sclerosing cholangitis) or bile duct stones. Also, we excluded narrative reviews (other than SRs) due to the absence of pre-specified eligibility criteria and systematic methodology, as well as SRs of SRs, commentaries, conference proceedings, and editorials.

Data Collection

Two reviewers (XC and HS) independently extracted data using pre-specified data collection forms. Discrepancies were resolved through discussion. Data extraction included SR characteristics (e.g. the inclusion criteria, intervention type, numbers of included studies and participants, types of study design, quality assessment of studies, analytical approach, and conclusions) and original study characteristics included in the SRs (e.g. numbers of participants and events, and intervention type). The primary outcome was postoperative mortality. The secondary outcomes were overall drainage-related morbidity, drainage-related cholangitis and pancreatitis, overall postoperative morbidity, postoperative major morbidity (Clavien-Dindo grade III-IV), infectious morbidity, liver failure, seeding metastasis, and long-term survival. It should be noted that for this study, the setting of the outcome indicator ‘long-term survival’ was modified from the registered protocol (CRD42019141412). The final literature survey revealed that longterm survival was reported in a single SR only (comparing BD with no BD), hence, it was deemed appropriate to include long-term survival as a secondary outcome measure.

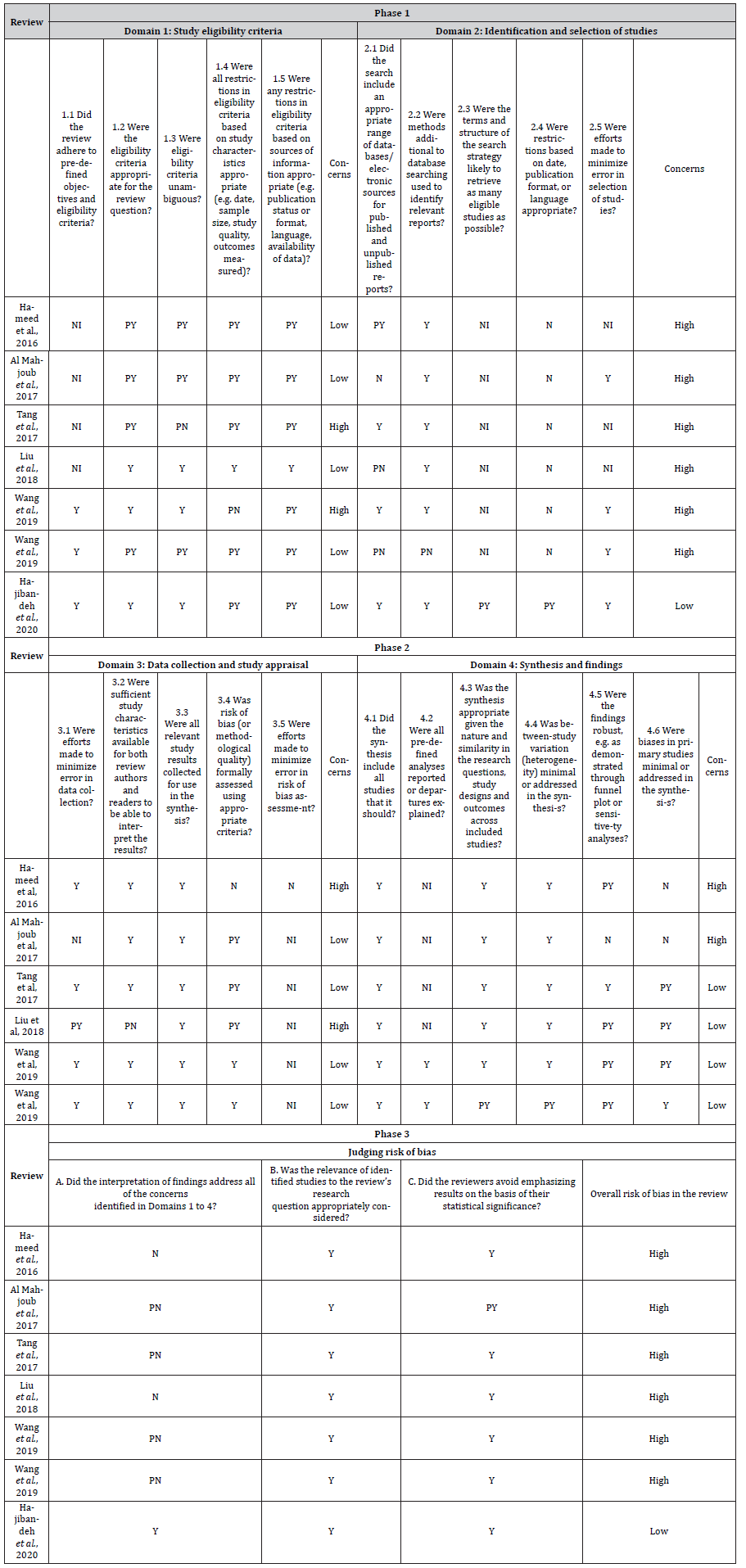

Risk-of-Bias Assessment

Two investigators (XC and HS) independently assessed the risk of bias for each included SR using the Risk of Bias in Systematic reviews (ROBIS) tool [30], a reliable and widely used appraisal instrument [31,32]. All disagreements were solved by discussion. The ROBIS tool includes 3 phases [30], of which the first phase assesses relevance (optional). The second phase covers 4 domains (21 items): study eligibility criteria, identification and selection of studies, data collection and study appraisal, and synthesis and findings. The third phase evaluates the overall risk of bias in the SRs. The items are rated as yes, probably yes, probably no, no, and no information. As PRISMA [33] and ROBIS [30] recommended, we assigned a rating of “low risk of bias”, “high risk of bias”, or “unclear risk of bias” to the overall risk of bias, instead of a summary score, because the latter may mask critical weaknesses decreasing the confidence in the results of a SR [33,34].

Data Synthesis

Data were evaluated using qualitative synthesis. Descriptive statistics were reported as frequency (percentage) when possible. We reported summary estimates of preoperative BD (EBD and/ or PTBD) effects on primary and secondary outcomes, as relative risk (RR) or odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence interval (CI) for dichotomous data, and hazard ratios (HR) with 95% CIs for timeto- event data. Because many included SRs comprised data from overlapping studies, a meta-analysis could not be performed.

Results

Study Selection

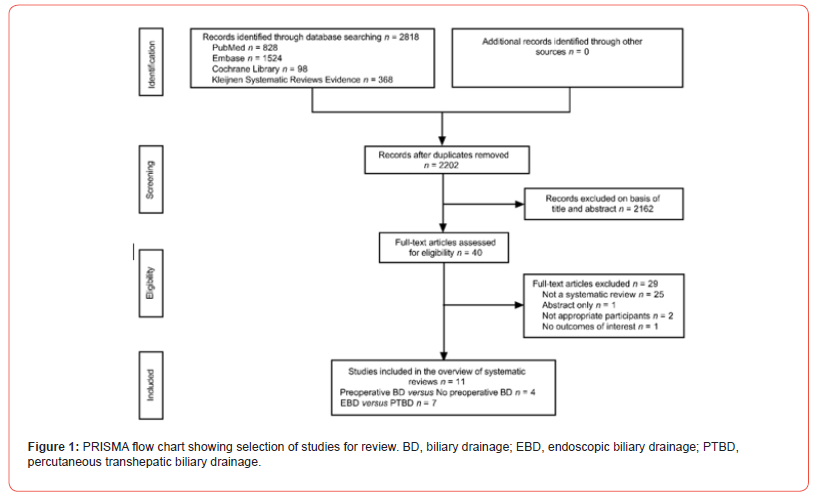

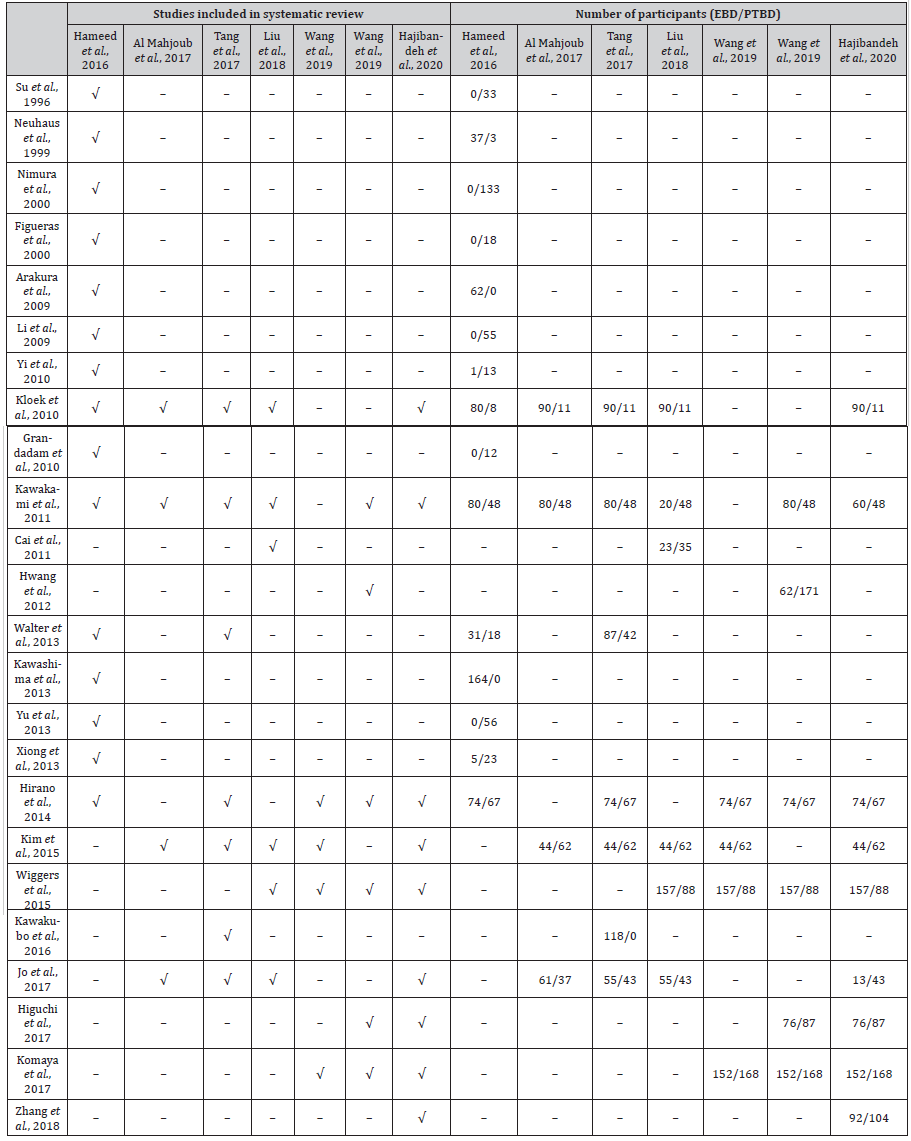

The database searches identified 2818 records including 6380 patients. After de-duplicating, screening titles and abstracts, 2778 records were excluded. Through completely reviewing the full text of the remaining 40 articles, we included 11 eligible SRs with metaanalyses. The included 11 SRs are published in English language, and no studies in a language other than English, were eligible for inclusion in the present study. No additional studies were eligible for inclusion after checking the references of included studies. Of eleven included SRs, four compared preoperative BD with no preoperative BD, while seven compared EBD with PTBD in patients with pCCA (Figure 1). The excluded full-text reports with reasons are presented in Table S1 (Supplementary file).

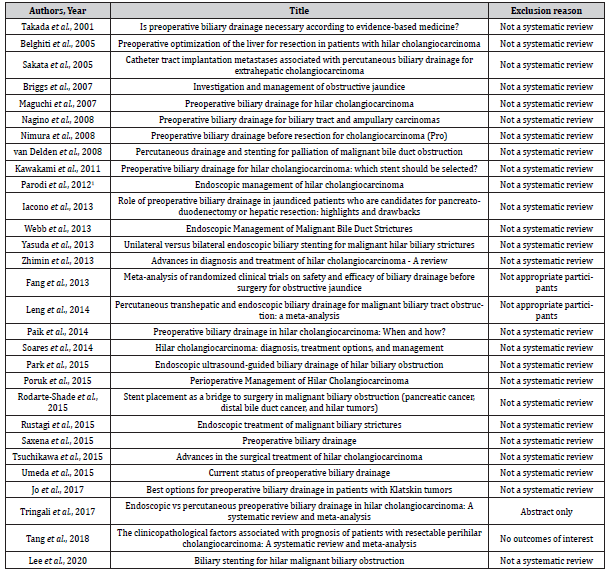

Table S1:List of excluded full text reviewed studies with reasons.

Comparison of Effects between Preoperative BD and No Preoperative BD in Resectable pCCA Study Characteristics

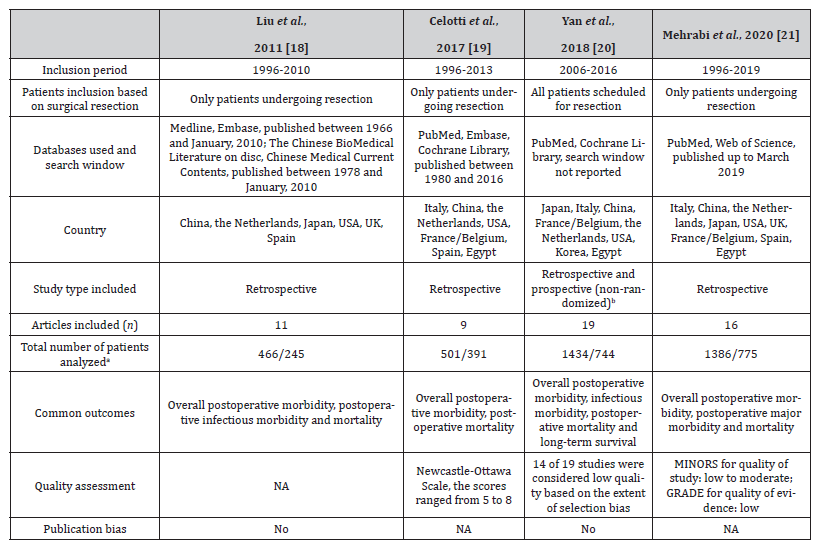

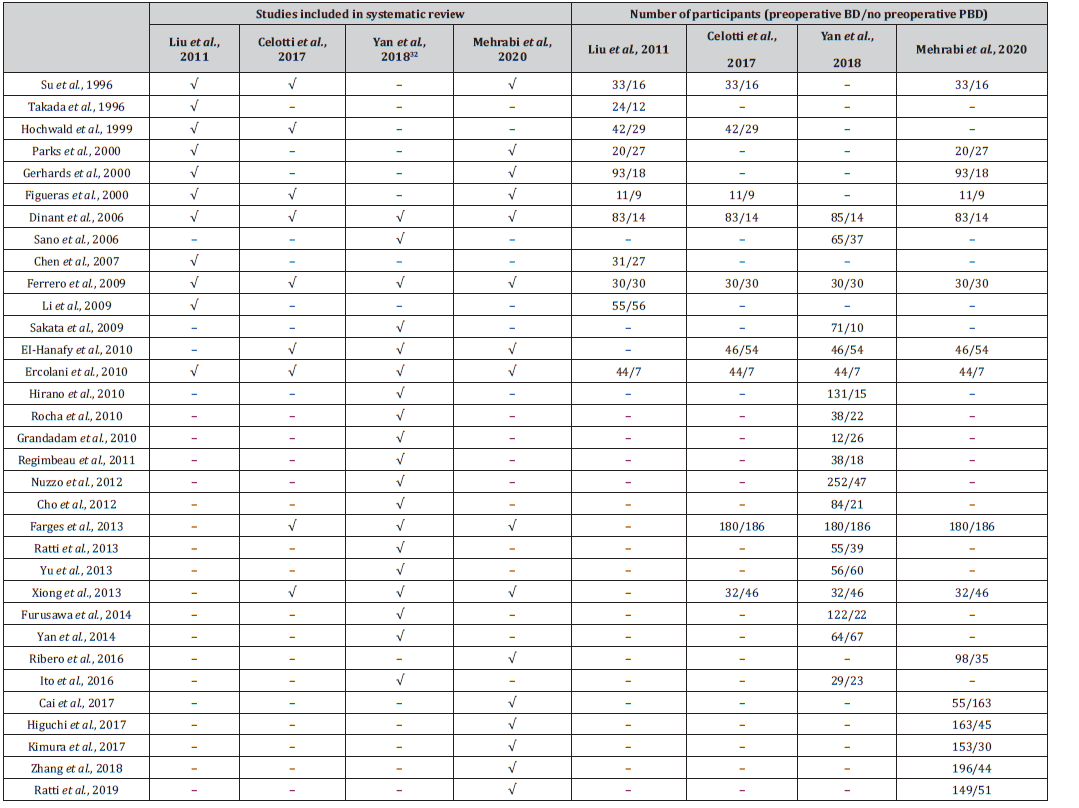

Characteristics of the four SRs [18-21] evaluating the effects of preoperative BD are shown in Table 1. These SRs [18-21] reported 33 unique studies, ranging from 9 to 19 studies with 711 to 2178 participants per individual SR. Eleven studies were repeatedly included in at least two SRs. Three [18,19,21] of four SRs only included participants who underwent resection. The other SR [20] also included participants where metastatic spread prevented actual resection. All original studies included were retrospective except for a single prospective cohort study [35]. The quality of included original studies was low to moderate [19-21]. The SR by Liu et al. [18] reported 252 (54.1%) participants receiving external drainage, 196 (42.1%) internal drainage, and 18 (3.8%) receiving a combination of internal and external drainage among 466 drained participants. Two SRs reported mean preoperative total bilirubin levels of 9.6 18 and 4.6 mg/dL20 in the drained patients, and 16.3 [18] and 15.8 mg/dL [20] in the patients without drainage, respectively. The mean duration between BD initiation and hepatic resection was 22.8 [18] and 30.8 days [20], respectively.

Table 1:Characteristics of included systematic reviews for comparison between preoperative BD and no preoperative BD in patients with resectable pCCA.

(a) The total number of patients is presented as preoperative BD/no preoperative BD. (b) Note that, Yan et al. [20] classified a prospective study 35 as retrospective study in their systematic review. BD, biliary drainage; pCCA, perihilar cholangiocarcinoma; MINORS, Methodological index for non-randomized studies; GRADE, Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation; NA, not applicable

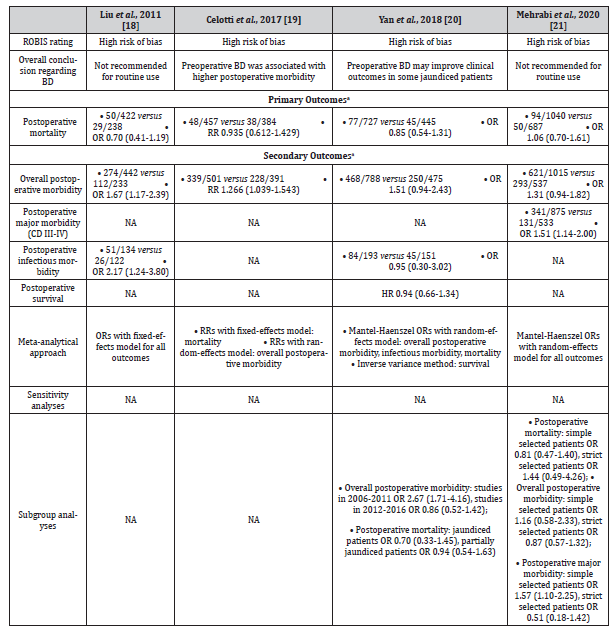

Risk of Bias of Included Systematic Reviews

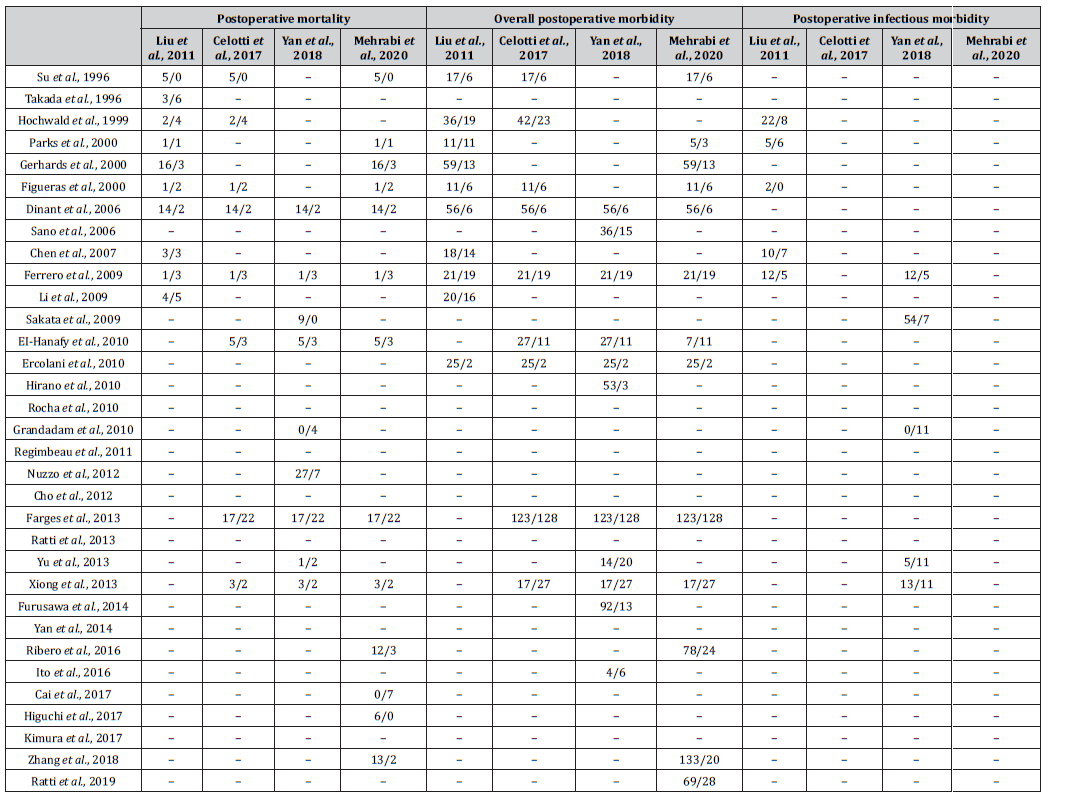

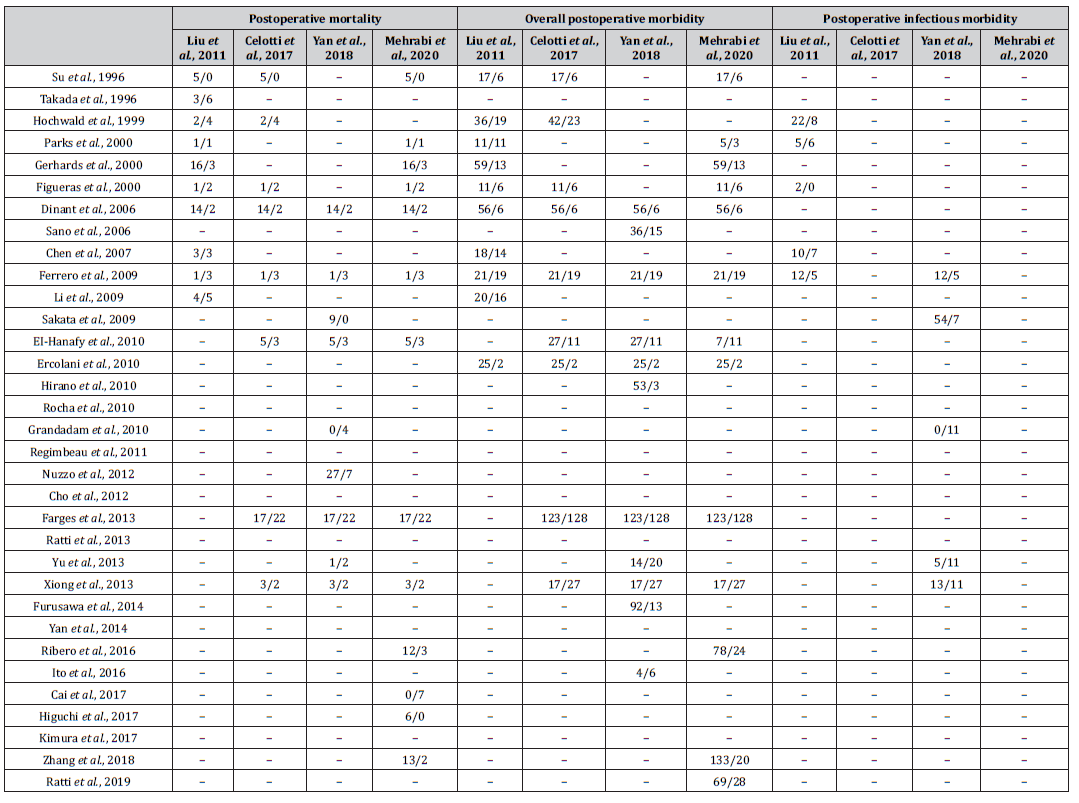

All SRs 18-21 were rated as “at high risk of bias” using ROBIS assessment (Table S2). The Cohen’s kappa coefficient for interrater agreement between the two reviewers was 0.76. One SR [18] was classified as “high risk of bias” mainly due to lacking quality assessment of original studies. The high risk of bias rating in the remaining SRs [19-21] was due to a number of concerns, such as language restrictions, lack of search window, not considering bias of primary studies in the synthesis, and incomplete reporting of independence in studies identification and data extraction. Besides, the numbers of included studies and abstracted participants and events were variable across the SRs [18-21] (Tables S3-S4), reflecting a combination of difference in period, inclusion criteria, or carelessness.

Effects of preoperative BD on secondary outcomes Overall Postoperative Morbidity

All SRs 18-21 reported on overall postoperative morbidity (Table 2). Of these, two demonstrated that preoperative BD was associated with significantly higher overall postoperative morbidity compared to immediate surgery (OR 1.67, 95% CI 1.17-2.39 [18] and RR 1.266, 95% CI 1.039-1.543 [19]), however, the other two SRs [20,21] found no significant difference between two groups. Through subgroup analysis, Yan et al. [20] showed higher overall postoperative morbidity in the preoperative BD group in the early 5 years’ studies (2006-2011) (OR 2.67, 95% CI 1.71-4.16), but not in the late 5 years’ studies (2012-2016).

Table 2:Assessment of meta-analytical methods and results in systematic reviews comparing preoperative BD with no preoperative BD in patients with resectable pCCA.

(a) Outcomes are presented as numbers of events/numbers of participants and preoperative BD versus no preoperative BD. The effect measures are presented as point estimates with the 95% confidence intervals. BD, biliary drainage; pCCA, perihilar cholangiocarcinoma; ROBIS, Risk of Bias in Systematic reviews; OR, odds ratio; RR, relative risk; HR, hazard ratios; CD, Clavien-Dindo grade; NA, not applicable.

Table S2:Assessment with ROBIS for risk of bias of systematic reviews comparing preoperative BD with no preoperative BD in patients with resectable pCCA.

ROBIS, Risk Of Bias In Systematic reviews; BD, biliary drainage; pCCA, perihilar .

cholangiocarcinoma; Y, Yes; PY, Probably yes; PN, Probably no; N, No; NI, No information.

Table S3:Number of studies and participants in systematic reviews for the comparison between preoperative BD and no preoperative BD in patients with resectable pCCA.

BD, biliary drainage; pCCA, perihilar cholangiocarcinoma.

Table S4:Number of abstracted events included in systematic reviews for the comparison between preoperative BD and no preoperative BD in patients with resectable pCCA..

BD, biliary drainage; pCCA, perihilar cholangiocarcinoma.

Effects of Preoperative BD on Primary Outcome Postoperative Mortality

All SRs [18-21] reported postoperative mortality in patients with pCCA (Table 2). These SRs consistently showed no statistically significant difference in postoperative mortality between patients with and without preoperative BD (OR 0.70, 95% CI 0.41-1.19 [18]; RR 0.935, 95% CI 0.612-1.429 [19]; OR 0.94, 95% CI 0.54- 1.63 [20]; and OR 1.06, 95% CI 0.70-1.61 [21]). However, these findings were derived from unadjusted ORs or RR. The definitions of mortality were variable and ranged from postoperative day 30 to 90 [10,14,36-38].

Postoperative Major Morbidity

Postoperative major morbidity was reported by one SR 21 revealing significantly higher major morbidity in the preoperative BD group (OR 1.51, 95% CI 1.14-2.00) (Table 2). However, due to different indications for BD in the original studies, Mehrabi et al. 21 performed a subgroup analysis. Patients were classified into a simple criteria group where preoperative BD was routinely used in all jaundiced patients, and a strict criteria group where preoperative BD was performed in patients with cholangitis and/or total bilirubin levels ≥ 15.0 mg/dL and/or inadequate future liver remnant (FLR) volume in addition to jaundice [21]. They found that preoperative BD was associated with increased postoperative major morbidity in ‘simple criteria’ patients (OR 1.57, 95% CI 1.10- 2.25), but not in strictly selected patients (OR 0.51, 95% CI 0.18- 1.42) [21].

Postoperative Infectious Morbidity

Of the two SRs that reported on postoperative infectious morbidity, one 18 showed a significant increase of infectious morbidity in patients receiving preoperative BD (OR 2.17, 95% CI 1.24-3.80) (Table 2). However, the infectious morbidity was similar in the other SR [20]. Celotti et al. [19] evaluated postoperative wound infections, showing significantly higher infection rates in the preoperative BD group (RR 2.035, 95% CI 1.041-3.977).

Postoperative Long-Term Survival

Postoperative long-term survival was assessed by one SR [20] and no difference between drained and undrained patients was observed (Table 2).

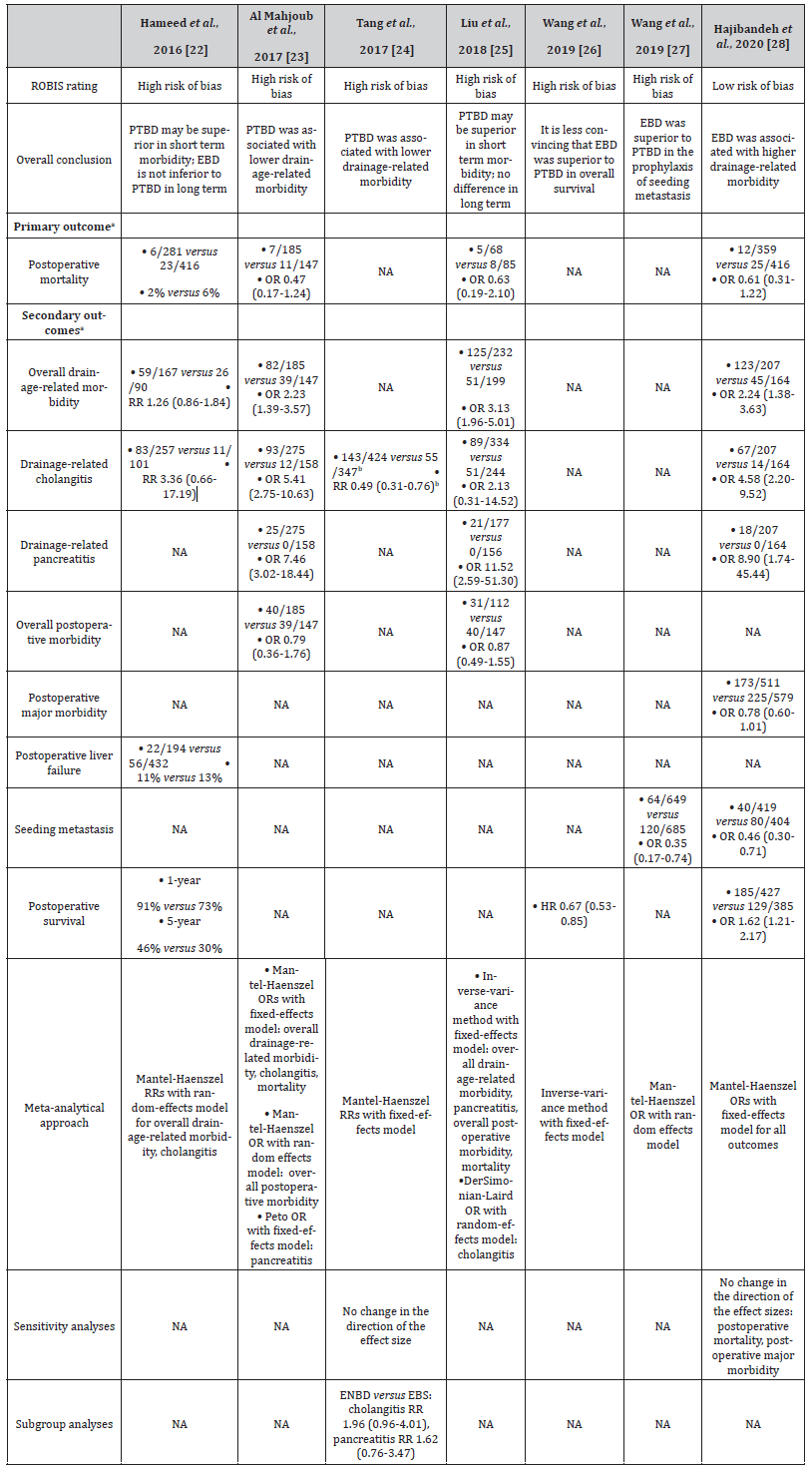

Comparison of Effects between EBD and PTBD in Resectable pCCA Study Characteristics

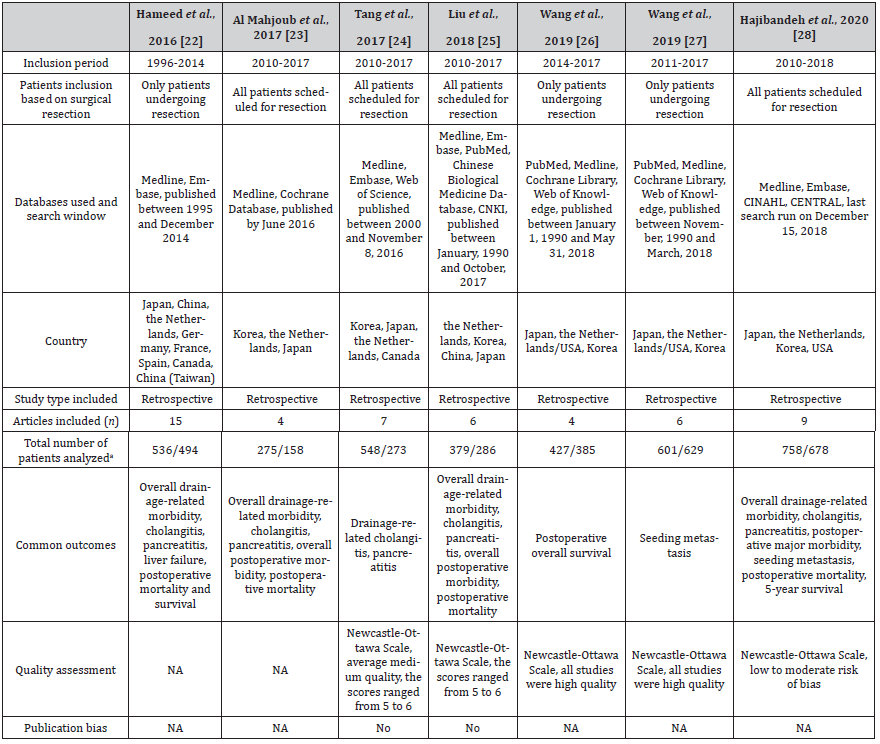

Characteristics of the seven SRs [22-28] investigating the effect of EBD compared to PTBD are presented in Table 3. These SRs included 24 original studies in total, ranging from 4 to 15 studies with 433 to 1230 participants per SR. Eight studies were repeatedly included in at least two SRs. Three [22,26,27] of seven SRs only included participants who underwent resection. All original studies included were retrospective studies. The quality of included original studies was moderate to high [24-28]. One SR [27] reported preoperative total bilirubin levels, ranging from 5.2 to 9.6 mg/dL and 8.4 to 12.0 mg/dL in the EBD and PTBD group, respectively. One SR reported median duration between drainage and surgery of 19 and 15 days in the EBD and PTBD group, respectively [22]. Patients receiving PTBD had more advanced tumors compared to those receiving EBD in terms of Bismuth type IV [27,28] and American Joint Committee on Cancer classification T3/4 stage [26,28].

Table 3:Characteristics of included systematic reviews for the comparison between EBD and PTBD in patients with resectable pCCA..

(a) The total numbers of patients are presented as EBD/PTBD. EBD, endoscopic biliary drainage; PTBD, percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage; pCCA, perihilar cholangiocarcinoma; CNKI, China National Knowledge Infrastructure; CINAHL, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature; CENTRAL, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials; NA, not applicable.

Risk of bias of Included Systematic Reviews

All but one SR [22-27] were classified as “at high risk of bias” using the ROBIS tool (Table S5). A single SR [28] was rated as “at low risk of bias”. The Cohen’s kappa coefficient for inter-rater agreement was 0.77. Four SRs [24-27] received the rating at high risk of bias mainly because of the restrictions in publication date and language. One SR [22] was assessed as high risk of bias due to the absence of quality assessment of the included studies and restrictions in publication date. The remaining SR 23 rated as high risk of bias was due to the restriction in language and a lack of appropriate range of search databases and sensitivity analysis in addition, the numbers of studies incorporated and participants and outcomes abstracted were reported inconsistently across the SRs [22-28] (Tables S6-S7).

Table S5:Assessment with ROBIS for risk of bias of systematic reviews comparing EBD with PTBD in patients with resectable pCCA.

EBD, endoscopic biliary drainage; PTBD, percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage; pCCA, perihilar cholangiocarcinoma.

Table S6:Number of studies and participants in systematic reviews for the comparison between EBD and PTBD in patients with resectable pCCA.

EBD, endoscopic biliary drainage; PTBD, percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage; pCCA, perihilar cholangiocarcinoma.

Table S7:Number of abstracted events included in systematic reviews for the comparison between EBD and PTBD in patients with resectable pCCA

EBD, endoscopic biliary drainage; PTBD, percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage; pCCA, perihilar cholangiocarcinoma.

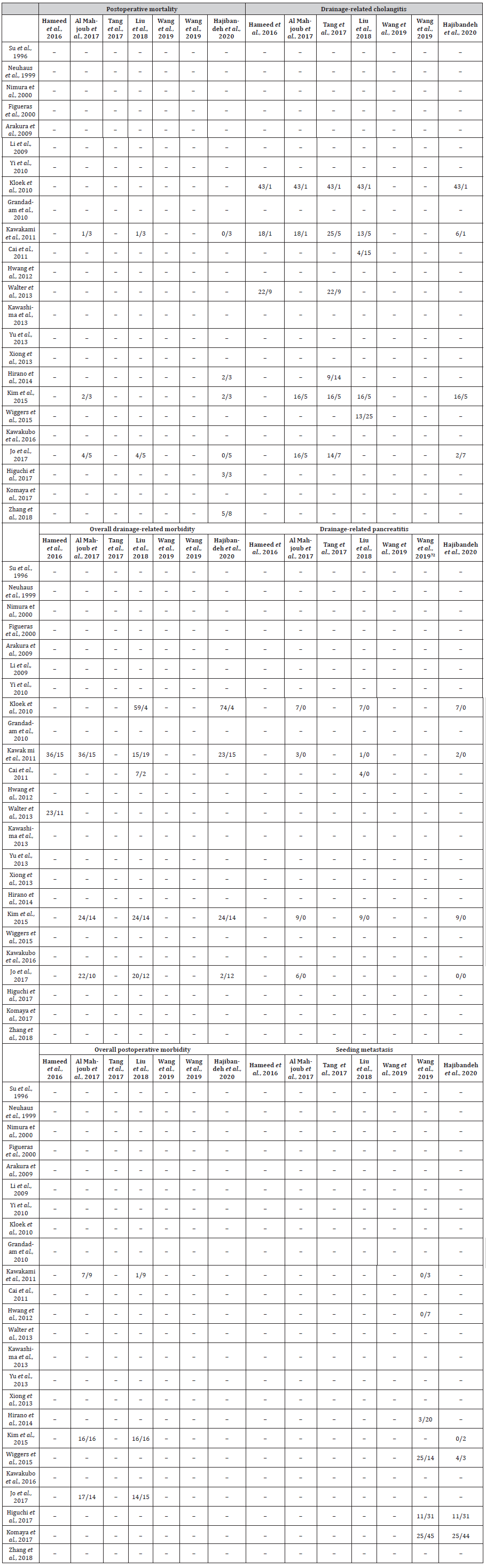

Comparison of Effects between EBD and PTBD on Primary Outcomes Postoperative Mortality

Four SRs [22,23,25,28] compared the effect of EBD versus PTBD on postoperative mortality (Table 4). Of these, three showed no statistically significant difference between the EBD group and the PTBD group (OR 0.47, 95% CI 0.17-1.24 [23]; OR 0.63, 95% CI 0.19-2.10 [25]; and OR 0.61, 95% CI 0.31-1.22 [28]). The remaining SR 22 reported the percentage of deaths following resection, viz. 2% (6/281) and 6% (23/416) in EBD group and PTBD group, respectively (p = 0.028).

Comparison of Effects between EBD and PTBD on Secondary Outcomes Overall Drainage-Related Morbidity

Four SRs [22,23,25,28] evaluated overall drainage-related morbidity. Three SRs demonstrated significantly higher drainagerelated morbidity following an EBD procedure compared to PTBD (OR 2.23, 95% CI 1.39-3.57 [23]; OR 3.13, 95% CI 1.96-5.01 [25]; and OR 2.24, 95% CI 1.38-3.63 [28]) (Table 4). However, this significant difference was not noted in the SR by Hameed et al. [22].

Drainage-Related Cholangitis

Of the five SRs [22-25,28] assessing drainage-related cholangitis, three pointed towards significantly higher cholangitis rates in the EBD group compared to the PTBD group (OR 5.41, 95% CI 2.75-10.63 [23]; RR 0.49, 95% CI 0.31-0.76 (PTBD versus EBS) [24]; and OR 4.58, 95% CI 2.20-9.52 [28]) (Table 4). However, cholangitis rates were not affected by drainage procedure in the two other SRs [22,25].

Drainage-Related Pancreatitis

Drainage-related pancreatitis was assessed by three SRs [23,25,28]. The pancreatitis rates were consistently significantly higher in the EBD group compared to the PTBD group (OR 7.46, 95% CI 3.02-18.44 [23]; OR 11.52, 95% CI 2.59-51.30 [25]; and OR 8.90, 95% CI 1.74-45.44 [28]) (Table 4).

Overall Postoperative Morbidity

Two SRs 23, 25 reported overall postoperative morbidity, which was not significantly different between the two drainage procedures (Table 4).

Table 4:Assessment of meta-analytical methods and results in systematic reviews comparing EBD with PTBD in patients with resectable pCCA.

(a) Outcomes are presented as numbers of events/numbers of participants and EBD versus PTBD. The effect measures are presented as point estimates with the 95% confidence intervals. (b) Tang et al. 24 presented and calculated drainage-related cholangitis rates based on PTBD versus EBD. EBD, endoscopic biliary drainage; PTBD, percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage; pCCA, perihilar cholangiocarcinoma; ENBD, endoscopic nasobiliary drainage; EBS, endoscopic biliary stenting; OR, odds ratio; RR, relative risk; HR, hazard ratios; NA, not applicable.

Postoperative Major Morbidity

One SR [28] assessed postoperative major morbidity and revealed no significant differences between EBD with PTBD (Table 4).

Postoperative Liver Failure

Postoperative liver failure rates were evaluated in one SR [22], where similar incidence rates were observed, 11% (22/194) and 13% (56/432) in the EBD and PTBD group, respectively (p = 0.570) (Table 4).

Seeding Metastasis

Two SRs reported the incidence of drainage-related seeding metastasis and unanimously showed lower rates in the EBD group (OR 0.27, 95% CI 0.13-0.56 [27] and OR 0.46, 95% CI 0.30-0.71 [28]) (Table 4).

Postoperative Long-Term Survival

Of the three SRs [22,26,28] assessing postoperative survival, Wang et al. [26] and Hajibandeh et al. [28] revealed that patients receiving EBD had longer overall survival (HR 0.67, 95% 0.53- 0.85) and 5-year survival (OR 1.62, 95% CI 1.21-2.17), respectively, then those receiving PTBD (Table 4). Hameed et al. 22 showed that median 1-year postoperative survival was 91% and 73%, 5-year survival 46% and 30% in EBD and PTBD group, respectively.

Discussion

We performed a SR of SRs to assess the effect and route of preoperative BD in patients with resectable pCCA. The available evidence reflected conflicting results, and identified substantial variation in data abstraction and statistical methods, and high risk of bias in most included SRs. Preoperative BD may need to be used in strictly selected patients with resectable pCCA. EBD might be associated with more short-term drainage-related morbidity compared to PTBD in patients with resectable pCCA. However, EBD might be related with better long-term outcomes after surgery. All but one SR included in the present study are rated as high risk of bias according to ROBIS assessment. Most SRs [19,20,22-27] had restrictions in publication date and language. Three SRs [18,22,23] did not report quality assessment of original studies. Additionally, there is considerable variability in the inclusion of studies and the numbers of participants and events abstracted across the SRs. These differences could be caused by variable period of study inclusion, inclusion criteria, and data extraction errors.

The errors in data extraction procedure are a vital source of bias in SRs [39]. The influence of risk of bias on pooled results could underestimate or overestimate the actual intervention effects, resulting in a limitation of the validity of the conclusions [40]. The indications for preoperative BD have not reached unanimity. Elevated serum bilirubin levels are generally used as indicator for BD. A recent study demonstrated that preoperative BD should be performed when serum bilirubin ≥ 6.0 mg/dL and not recommended when bilirubin levels < 2.5 mg/dL 6. Imaging of the liver plays an important role in the management of pCCA and the use of BD [41]. FLR volume assessment by computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is another vital determinant to perform BD [42]. For patients with FLR volumes < 50%, preoperative drainage can be beneficial to decrease mortality, but not for large FLR volumes > 50% [42]. Normalization of bile duct diameters in the FLR on ultrasound examination and 20% or more decrease of total bilirubin levels after 7 days, are considered indicators of therapeutic success of BD [9].

The SR of Mehrabi et al. revealed that preoperative BD was not associated with postoperative major morbidity in strictly selected patients with cholangitis and/or high bilirubin levels (≥ 15.0 mg/ dL) and/or inadequate FLR. In contrast, increased postoperative major morbidity was observed in simple criteria patients where preoperative BD was routinely used in all jaundiced patients [21]. We found that postoperative mortality was similar between drained and undrained patients. This finding seems consistent with previous studies [43,44], which concluded that preoperative BD does not improve postoperative mortality. However, the latter conclusions were derived from unadjusted odds ratios (ORs) or relative risk (RR), without considering tumor features and resection methods. Hence, we cannot decisively conclude whether preoperative BD has effects on postoperative mortality.

EBD can be associated with high drainage-related morbidity caused by retrograde bacterial contamination from the proximal small intestine [15,28]. Our study demonstrated that overall drainage-related morbidity and pancreatitis rates were higher in the EBD group than in the PTBD group (ORs from 2.23 to 3.13, 7.46 to 11.52, respectively). Hameed et al. [22] indicated no differences in overall drainage-related morbidity between the two drainage routes. However, they included fewer original articles in their SR, which was therefore more susceptible to publication bias. Although PTBD seems to induce less drainage-related morbidity, other major complications must be considered, including tumor seeding. We found that PTBD was associated with significantly higher incidence of seeding metastasis, which was consistent with other studies [16,45]. Our analysis showed that mortality was not statistical different in EBD versus PTBD in most included SRs.

However, a recently published Dutch randomized controlled trial (RCT) [9] demonstrated significantly higher mortality in PTBD group compared to EBD group [9]. Importantly, in the RCT both perioperative and postoperative mortality were assessed. PTBD significantly increased perioperative mortality, with 3 of 11 fatalities occurring before surgery in patients receiving PTBD [9]. Most included SRs did not state whether internal or external drainage was used. However, internal drainage elicits a different physiological response compared to external drainage. The latter drainage mode abrogates the digestive, signaling and antimicrobial roles of bile salts in EHC. Diminished activation of the ileal bile salt receptor farnesoid X receptor (FXR) can result in the loss of negative feedback control of hepatic bile salt synthesis and attendant bile salt overload and hepatotoxicity [46]. Importantly, bile salt signaling and maintained bile salt homeostasis is required for proper regrowth of the remnant liver [47,48]. Liver regeneration volumes and rates are positively associated with serum bile salts levels in patients undergoing major hepatectomy [49]. However, bile can be easily given back orally with external drainage mode [50].

Overall, preoperative BD has merits and limitations. Preoperative BD can decompress the biliary obstruction, mitigate intrahepatic bile salt overload, relieve cholangitis, and improve liver function [8,10,11]. Moreover, the restoration of bile flow to the small intestine may improve epithelium function of gut and decrease bacterial translocation [51]. However, preoperative BD can result in complications. For example, PTBD is related to bile leakage and vascular complications including haemobilia and pseudoaneurysm [52]. In addition, tumor seeding metastasis might be another potential risk [27]. EBD can be associated with drainagerelated cholangitis and pancreatitis, which may have nonspecific clinical manifestations [23,28]. Our SR has certain strengths. First, a pre-specified protocol was followed in the review procedure, and a comprehensive and robust search strategy by two information experts was used to identify studies. Second, we used a validated instrument, ROBIS tool, to specifically assess the risk of bias in the included SRs. Finally, identification of studies, data collection, and study appraisal was performed by two reviewers independently to minimize potential bias.

Our SR also has several limitations. First, drained patients often present with more complex clinical conditions than undrained patients, such as larger tumor sizes and impaired liver function. In addition, the resections (and prior embolization’s) performed on the patients which may be the important determinant of both perioperative and long-term outcomes, were not analyzed in the included SRs. Second, eight [19,20,22-27] of eleven SRs had restrictions in publication date and/or English language. All but one SR did not include unpublished or grey literature in their selection criteria [18-27]. This could narrow the breadth of data sources and exclude potentially eligible studies. Third, because many original studies were repeatedly included in at least two SRs and there was heterogeneity in the definitions of outcomes, we could not calculate overall pooled estimates. Fourth, the ORs and/or RRs of primary and secondary outcomes were only reported in only few SRs, therefore, the results need to be interpreted with caution. Finally, all but one of the original studies included in the SRs 18-28 had a retrospective design, resulting in selection bias.

It is unclear from the SRs [22-28] if in PTBD procedures bile was given back to the patients (to restore functionality of the EHC). In the Dutch RCT, external drainage of bile may be a reason for the increased mortality in patients receiving PTBD [9]. Pre-clinical studies have demonstrated FXR-mediated acceleration of liver growth in absence [53] and presence [48] of partial hepatectomy. Recent clinical trials have also shown that FXR activation can improve cholestasis in patients with primary biliary cirrhosis [54] and primary sclerosing cholangitis [55], and liver histological features in patients with primary biliary cholangitis [56]. Bile salt supplementation or FXR agonism may have the potential to replace preoperative BD to improve perioperative outcomes in patients with pCCA, considering the activation of pathways involved in bile salt homeostasis and liver regeneration [46-48].

Conclusion

The present SR of SRs comprehensively assesses the effectiveness of PBD versus no PBD, and the superiority of EBD versus and PTBD on perioperative and long-term outcomes in patients with resectable pCCA. The preoperative BD might need to be performed in strictly selected patients in terms of cholangitis, bilirubin levels and future liver remnant volume to avoid increased postoperative major morbidity. EBD might be associated with higher short-term drainage-related morbidity compared to PTBD. But EBD might be related with more favorable postoperative long-term outcomes. The available evidence has high risk of bias. Large sample sizes and/or international multicentre RCTs are urgently needed to assess the value of preoperative BD in surgical management of patients with resectable pCCA.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank R. Elands, from Maastricht University Library, for her collaboration in this work.

Conflict of Interest Statement

JK is the owner of Kleijnen Systematic Reviews (KSR) Ltd. KSR Ltd provided support for the literature search. The authors declare no other conflict of interest.

Authors’ Contributions

XC, FS, JK, SOD conceived the study; XC, JK searched the literature; XC, HS collected the data; XC, HS, FS, MD, BGK, CL, UN, JK, SOD analyzed and interpreted the data; XC, FS, SOD wrote the manuscript; All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Appendix

Supplementary file

Appendix S1 Search strategy used for electronic databases.

PubMed

#1 Klatskin tumor[MeSH Terms]

#2 Klatskin tumor*[ti/ab]

#3 Klatskin’s tumor*[ti/ab]

#4 (bile duct neoplasms[MeSH Terms]) OR

cholangiocarcinoma[MeSH Terms]

#5 bile duct[ti/ab]

#6 ((((tumor*[ti/ab]) OR tumour*[ti/ab]) OR carci*[ti/ab])

OR cancer*[ti/ab]) OR neoplas*[ti/ab]

#7 #5 AND #6

#8 cholangiocarcinoma*[ti/ab]

#9 #4 OR #7 OR #8

#10 ((hilar[ti/ab]) OR perihilar[ti/ab]) OR proximal[ti/ab]

#11 #9 AND #10

#12 hepatic duct[ti/ab]

#13 #6 AND #12

#14 bile duct bifurcation carcinoma*[ti/ab]

#15 #1 OR #2 OR #3 OR #11 OR #13 OR #14

#16 cholangiopancreatography, endoscopic retrograde[MeSH

Terms]

#17 ((((bile drain*[ti/ab]) OR bile duct drain*[ti/ab]) OR bile

tract drain*[ti/ab]) OR biliary drain*[ti/ab]) OR nasobiliary

drain*[ti/ab]

#18 (biliary decompression[ti/ab]) OR biliary stent*[ti/ab]

#19 ((((((endoscopic retrograde

cholangiopancreatography[ti/ab]) OR endoscopic retrograde

cholangiopancreatographies[ti/ab]) OR endoscopic retrograde

cholangiography[ti/ab]) OR endoscopic cholangiography[ti/

ab]) OR endoscopic cholangiopancreatography[ti/ab]) OR

endoscopic pancreatocholangiography[ti/ab]) OR ERCP[ti/ab]

#20 #16 OR #17 OR #18 OR #19

#21 ((morbidity[MeSH Terms]) OR mortality[MeSH Terms])

OR survival[MeSH Terms]

#22 ((((morbidity[ti/ab]) OR complicat*[ti/ab]) OR

mortality[ti/ab]) OR death rate[ti/ab]) OR survival[ti/ab]

#23 #21 OR #22

#24 #15 AND #20 AND #23

Embase

#1 Klatskin tumor/

#2 (‘Klatskin tumor’ or ‘Klatskin tumors’ or ‘Klatskin’s tumor’

or ‘Klatskin’s tumors’).ab,ti.

#3 exp bile duct tumor/

#4 bile duct’.ab,ti.

#5 (tumor or tumors or tumour or tumours or cancer or

cancers or carci* or neoplas*).ab,ti.

#6 #4 and #5

#7 cholangiocarcinoma*.ab,ti.

#8 #3 or #6 or #7

#9 (hilar or perihilar or proximal).ab,ti.

#10 #8 and #9

#11 hepatic duct’.ab,ti.

#12 #5 and #11

#13 #1 or #2 or #10 or #12

#14 exp biliary tract drainage/

#15 endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography/

#16 (‘bile drainage’ or ‘bile duct drainage’ or ‘bile tract

drainage’ or ‘biliary drainage’ or ‘nasobiliary drainage’ or

‘biliary decompression’ or ‘biliary stent’ or ‘biliary stenting’).

ab,ti.

#17 (‘endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography’

or ‘endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatographies’ or

‘endoscopic retrograde cholangiography’ or ‘endoscopic

cholangiography’ or ‘endoscopic cholangiopancreatography’ or

‘endoscopic pancreatocholangiography’ or ERCP).ab,ti.

#18 #14 or #15 or #16 or #17

#19 exp morbidity/

#20 exp complication/

#21 exp mortality/

#22 exp survival/

#23 (morbidity or complicat* or mortality or ‘death rate’ or

survival).ab,ti.

#24 #19 or #20 or #21 or #22 or #23

#25 #13 and #18 and #24

Cochrane Library

#1 MeSH descriptor: [Klatskin Tumor] explode all trees

#2 (‘Klatskin tumor*’ or ‘Klatskin’s tumor*’):ti,ab,kw

#3 MeSH descriptor: [Bile Duct Neoplasms] explode all trees

#4 MeSH descriptor: [Cholangiocarcinoma] explode all trees

#5 (bile duct):ti,ab,kw

#6 (tumor* or tumour* or carci* or cancer* or

neoplas*):ti,ab,kw

#7 #5 and #6

#8 (cholangiocarcinoma*):ti,ab,kw

#9 #3 or #4 or #7 or #8

#10 (hilar or perihilar or proximal):ti,ab,kw

#11 #9 and #10

#12 (hepatic duct):ti,ab,kw

#13 #6 and #12

#14 (bile duct bifurcation carcinoma*):ti,ab,kw

#15 #1 or #2 or #11 or #13 or #14

#16 MeSH descriptor: [Cholangiopancreatography, Endoscopic

Retrograde] explode all trees

#17 (‘bile drain*’ or ‘bile duct drain*’ or ‘bile tract drain*’ or

‘biliary drain*’ or ‘nasobiliary drain*’):ti,ab,kw

#18 (‘biliary decompression’ or ‘biliary stent*’):ti,ab,kw

#19 (‘endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography’

or ‘endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatographies’ or

‘endoscopic retrograde cholangiography’ or ‘endoscopic

cholangiography’ or ‘endoscopic cholangiopancreatography’ or

‘endoscopic pancreatocholangiography’ or ERCP):ti,ab,kw

#20 #16 or #17 or #18 or #19

#21 MeSH descriptor: [Morbidity] explode all trees

#22 MeSH descriptor: [Mortality] explode all trees

#23 MeSH descriptor: [Survival] explode all trees

#24 (morbidity or complicat* or mortality OR death rate OR

survival):ti,ab,kw

#25 #21 or #22 or #23 or #24

#26 #15 and #20 and #25

References

- Razumilava N, Gores GJ (2014) Cholangiocarcinoma. The Lancet 383: 2168-2179.

- Khan SA, Tavolari S, Brandi G (2019) Cholangiocarcinoma: Epidemiology and risk factors. Liver Int 39 Suppl 1: 19-31.

- Blechacz B, Komuta M, Roskams T, Gores GJ (2011) Clinical diagnosis and staging of cholangiocarcinoma. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 8(9): 512-522.

- Mizuno T, Ebata T, Yokoyama Y, Igami T, Yamaguchi J, et al. (2022) Combined Vascular Resection for Locally Advanced Perihilar Cholangiocarcinoma. Ann Surg 275(2): 382-390.

- Nagino M, Ebata T, Yokoyama Y, Igami T, Sugawara G, et al. (2013) Evolution of surgical treatment for perihilar cholangiocarcinoma: a single-center 34-year review of 574 consecutive resections. Ann Surg 258(1): 129-140.

- Wronka KM, Grat M, Stypulkowski J, Bik E, Patkowski W, et al. (2019) Relevance of Preoperative Hyperbilirubinemia in Patients Undergoing Hepatobiliary Resection for Hilar Cholangiocarcinoma. J Clin Med 8(4): 458.

- Inamdar S, Slattery E, Bhalla R, Sejpal DV, Trindade AJ (2016) Comparison of Adverse Events for Endoscopic vs Percutaneous Biliary Drainage in the Treatment of Malignant Biliary Tract Obstruction in an Inpatient National Cohort. JAMA Oncol 2(1): 112-7.

- Lidsky ME, Jarnagin WR (2018) Surgical management of hilar cholangiocarcinoma at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. Ann Gastroenterol Surg 2(4): 304-312.

- Coelen RJS, Roos E, Wiggers JK, Besselink MG, Buis CI, et al. (2018) Endoscopic versus percutaneous biliary drainage in patients with resectable perihilar cholangiocarcinoma: a multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 3(10): 681-690.

- Farges O, Regimbeau JM, Fuks D, Le Treut YP, Cherqui D, et al. (2013) Multicentre European study of preoperative biliary drainage for hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Br J Surg 100(2): 274-283.

- Reiniers MJ, de Haan L, Weijer R, Wiggers JK, Jongejan A, et al. (2019) Effect of preoperative biliary drainage on cholestasis-associated inflammatory and fibrotic gene signatures in perihilar cholangiocarcinoma. Br J Surg 106: 55-58.

- Ramanathan R, Borrebach J, Tohme S, Tsung A (2018) Preoperative Biliary Drainage Is Associated with Increased Complications After Liver Resection for Proximal Cholangiocarcinoma. J Gastrointest Surg 22(11): 1950-1957.

- Ratti F, Cipriani F, Fiorentini G, Hidalgo Salinas C, Catena M, et al. (2019) Management of hilum infiltrating tumors of the liver: The impact of experience and standardization on outcome. Dig Liver Dis 51(1): 135-141.

- Xiong JJ, Nunes QM, Huang W, Pathak S, Wei AL, et al. (2013) Preoperative biliary drainage in patients with hilar cholangiocarcinoma undergoing major hepatectomy. World J Gastroenterol 19(46): 8731-8739.

- Kim KM, Park JW, Lee JK, Lee KH, Lee KT, et al. (2015) A Comparison of Preoperative Biliary Drainage Methods for Perihilar Cholangiocarcinoma: Endoscopic versus Percutaneous Transhepatic Biliary Drainage. Gut Liver 9(6): 791-799.

- Komaya K, Ebata T, Yokoyama Y, Igami T, Sugawara G, et al. (2017) Verification of the oncologic inferiority of percutaneous biliary drainage to endoscopic drainage: A propensity score matching analysis of resectable perihilar cholangiocarcinoma. Surgery 161(2): 394-404.

- Ribero D, Zimmitti G, Aloia TA, Shindoh J, Fabio F, et al. (2016) Preoperative Cholangitis and Future Liver Remnant Volume Determine the Risk of Liver Failure in Patients Undergoing Resection for Hilar Cholangiocarcinoma. J Am Coll Surg 223(1): 87-97.

- Liu F, Li Y, Wei Y, Li B (2011) Preoperative biliary drainage before resection for hilar cholangiocarcinoma: whether or not? A systematic review. Dig Dis Sci 56(3): 663-672.

- Celotti A, Solaini L, Montori G, Coccolini F, Tognali D, et al. (2017) Preoperative biliary drainage in hilar cholangiocarcinoma: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Surg Oncol 43(9): 1628-1635.

- Yan K, Tian J, Xu J, Fu Y, Zhang H, et al. (2018) The value of preoperative biliary drainage in hilar cholangiocarcinoma: A systematic review and meta analysis of 10 years' literatures. Int J Clin Exp Med 11: 3462-3472.

- Mehrabi A, Khajeh E, Ghamarnejad O, Nikdad M, Chang DH, et al. (2020) Meta-analysis of the efficacy of preoperative biliary drainage in patients undergoing liver resection for perihilar cholangiocarcinoma. Eur J Radiol 125: 108897.

- Hameed A, Pang T, Chiou J, Pleass H, Lam V, et al. (2016) Percutaneous vs. endoscopic pre-operative biliary drainage in hilar cholangiocarcinoma - a systematic review and meta-analysis. HPB 18(5): 400-410.

- Al Mahjoub A, Menahem B, Fohlen A, Dupont B, Alves A, et al. (2017) Preoperative Biliary Drainage in Patients with Resectable Perihilar Cholangiocarcinoma: Is Percutaneous Transhepatic Biliary Drainage Safer and More Effective than Endoscopic Biliary Drainage? A Meta-Analysis. J Vasc Interv Radiol 28(4): 576-582.

- Tang Z, Yang Y, Meng W, Li X (2017) Best option for preoperative biliary drainage in Klatskin tumor: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine 96(43): e8372.

- Liu JG, Wu J, Wang J, Shu GM, Wang YJ, et al. (2018) Endoscopic Biliary Drainage Versus Percutaneous Transhepatic Biliary Drainage in Patients with Resectable Hilar Cholangiocarcinoma: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A 28(9): 1053-1060.

- Wang L, Lin N, Xin F, Zeng Y, Liu J (2019) Comparison of long-term efficacy between endoscopic and percutaneous biliary drainage for resectable extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma with biliary obstruction: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Saudi J Gastroenterol 25(2): 81-88.

- Wang L, Lin N, Xin F, Ke Q, Zeng Y, et al. (2019) A systematic review of the comparison of the incidence of seeding metastasis between endoscopic biliary drainage and percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage for resectable malignant biliary obstruction. World J Surg Oncol 17(1): 116.

- Hajibandeh S, Hajibandeh S, Satyadas T (2020) Endoscopic Versus Percutaneous Preoperative Biliary Drainage in Patients with Klatskin Tumor Undergoing Curative Surgery: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Short-Term and Long-Term Outcomes. Surg Innov 27(3): 279-290.

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG (2009) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ 339: b2535.

- Whiting P, Savovic J, Higgins JP, Caldwell DM, Reeves BC, et al. (2016) ROBIS: A new tool to assess risk of bias in systematic reviews was developed. J Clin Epidemiol 69: 225-234.

- Ingoe HM, Coleman E, Eardley W, Rangan A, Hewitt C, et al. (2019) Systematic review of systematic reviews for effectiveness of internal fixation for flail chest and rib fractures in adults. BMJ Open 9(4): e023444.

- Siegfried N, Parry C (2019) Do alcohol control policies work? An umbrella review and quality assessment of systematic reviews of alcohol control interventions (2006 - 2017). PLoS One 14(4): e0214865.

- Beller EM, Glasziou PP, Altman DG, Hopewell S, Bastian H, et al. (2013) PRISMA for Abstracts: reporting systematic reviews in journal and conference abstracts. PLoS Med 10(4): e1001419.

- Shea BJ, Reeves BC, Wells G, Thuku M, Hamel C, et al. (2017) AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ 358: j4008.

- Regimbeau JM, Fuks D, Le Treut YP, Bachellier P, Belghiti J, et al. (2011) Surgery for hilar cholangiocarcinoma: a multi-institutional update on practice and outcome by the AFC-HC study group. J Gastrointest Surg 15(3): 480-8.

- Ferrero A, Lo Tesoriere R, Vigano L, Caggiano L, Sgotto E, et al. (2009) Preoperative biliary drainage increases infectious complications after hepatectomy for proximal bile duct tumor obstruction. World J Surg 33(2): 318-325.

- El-Hanafy E (2010) Pre-operative biliary drainage in hilar cholangiocarcinoma, benefits and risks, single center experience. Hepatogastroenterology 57(99-100): 414-419.

- Grandadam S, Compagnon P, Arnaud A, Olivie D, Malledant Y, et al. (2010) Role of preoperative optimization of the liver for resection in patients with hilar cholangiocarcinoma type III. Ann Surg Oncol 17(12): 3155-3161.

- Onasanya O, Iyer G, Lucas E, Lin D, Singh S, et al. (2016) Association between exogenous testosterone and cardiovascular events: an overview of systematic reviews. The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology 4(11): 943-956.

- Higgins JPT, Altman DG, Gotzsche PC, Juni P, Moher D, et al. (2011) The Cochrane Collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 343: d5928.

- Abdel Razek AAK, El-Serougy LG, Saleh GA, Shabana W, Abd El-Wahab R (2020) Liver Imaging Reporting and Data System Version 2018: What Radiologists Need to Know. J Comput Assist Tomogr 44(2): 168-177.

- Wiggers JK, Groot Koerkamp B, Cieslak KP, Doussot A, van Klaveren D, et al. (2016) Postoperative Mortality after Liver Resection for Perihilar Cholangiocarcinoma: Development of a Risk Score and Importance of Biliary Drainage of the Future Liver Remnant. J Am Coll Surg 223(2): 321-331.

- Zhang XF, Beal EW, Merath K, Ethun CG, Salem A, et al. (2018) Oncologic effects of preoperative biliary drainage in resectable hilar cholangiocarcinoma: Percutaneous biliary drainage has no adverse effects on survival. J Surg Oncol 117(6): 1267-1277.

- Cai Y, Tang Q, Xiong X, Li F, Ye H, et al. (2017) Preoperative biliary drainage versus direct surgery for perihilar cholangiocarcinoma: A retrospective study at a single center. Biosci Trends 11(3): 319-325.

- Hirano S, Tanaka E, Tsuchikawa T, Matsumoto J, Kawakami H, et al. (2014) Oncological benefit of preoperative endoscopic biliary drainage in patients with hilar cholangiocarcinoma. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci 21(8): 533-540.

- Schaap FG, Trauner M, Jansen PLM (2014) Bile acid receptors as targets for drug development. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 11(1): 55-67.

- Uriarte I, Fernandez-Barrena MG, Monte MJ, Latasa MU, Chang HC, et al. (2013) Identification of fibroblast growth factor 15 as a novel mediator of liver regeneration and its application in the prevention of post-resection liver failure in mice. Gut 62(6): 899-910.

- Huang W, Ma K, Zhang J, Qatanani M, Cuvillier J, et al. (2006) Nuclear receptor-dependent bile acid signaling is required for normal liver regeneration. Science 312(5771): 233-236.

- Otao R, Beppu T, Isiko T, Mima K, Okabe H, et al. (2012) External biliary drainage and liver regeneration after major hepatectomy. Br J Surg 99(11): 1569-1574.

- Yoshida Y, Ajiki T, Ueno K, Shinozaki K, Murakami S, et al. (2014) Preoperative bile replacement improves immune function for jaundiced patients treated with external biliary drainage. J Gastrointest Surg 18(12): 2095-2104.

- Sorrentino G, Perino A, Yildiz E, El Alam G, Sleiman MB, et al. (2020) Bile Acids Signal via TGR5 to Activate Intestinal Stem Cells and Epithelial Regeneration. Gastroenterology 159(3): 956-968.

- Venkatanarasimha N, Damodharan K, Gogna A, Leong S, Too CW, et al. (2017) Diagnosis and Management of Complications from Percutaneous Biliary Tract Interventions. Radiographics 37(2): 665-680.

- Olthof PB, Huisman F, Schaap FG, van Lienden KP, Bennink RJ, et al. (2017) Effect of obeticholic acid on liver regeneration following portal vein embolization in an experimental model. Br J Surg 104(5): 590-599.

- Hirschfield GM, Mason A, Luketic V, Lindor K, Gordon SC, et al. (2015) Efficacy of obeticholic acid in patients with primary biliary cirrhosis and inadequate response to ursodeoxycholic acid. Gastroenterology 148(4): 751-61.

- Kowdley KV, Vuppalanchi R, Levy C, Floreani A, Andreone P, et al. (2020) A randomized, placebo-controlled, phase II study of obeticholic acid for primary sclerosing cholangitis. J Hepatol 73(1): 94-101.

- Bowlus CL, Pockros PJ, Kremer AE, Pares A, Forman LM, et al. (2020) Long-Term Obeticholic Acid Therapy Improves Histological Endpoints in Patients with Primary Biliary Cholangitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 18(5): 1170-1178.

-

Xinwei Chang*, Hongxia Shen, Frank G. Schaap, Maxime J.L. Dewulf, Bas Groot Koerkamp, Christiaan van der Leij, Ulf P. Neumann, Jos Kleijnen8, and Steven W.M. Olde Damink. Effect and Route of Preoperative Biliary Drainage in Patients with Resectable Perihilar Cholangiocarcinoma: A Systematic Review of Systematic Reviews. Curr Tr Clin & Med Sci. 4(3): 2025. CTCMS.MS.ID.000589.

-

Perihilar cholangiocarcinoma; biliary drainage; systematic reviews; effect; route; mortality; iris publishers; iris publisher’s group

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.