Case Report

Case Report

Difficulties in Providing International Support for People with Disabilities in Cambodia

Shinnosuke Harada1*, Sumire Sato2, Anna Ueda3

1Faculty of Psychology, Iryo Sosei University, Fukushima, Japan

2Faculty of Psychology, Iryo Sosei University, Fukushima, Japan

2Community Psychology, Counseling, and Family Therapy Department, St. Cloud State University, Minnesota, USA

Shinnosuke Harada, PhD, Faculty of Psychology, Iryo Sosei University, Fukushima, Japan.

Received Date: May 31, 2022; Published Date: June 09, 2022

Abstract

Cambodia’s domestic policy towards supports for people with disabilities is not well-developed, and support from abroad has been historically

essential. However, support from overseas is not yet sufficiently advanced, nor has it been consistent. In this study, we interviewed three people

engaged in support activities to identify the factors that are causing difficulties for foreign supporters or support groups in developing supports in

Cambodia. The following five points were identified as the main difficulties in developing education and welfare support for people with disabilities

in Cambodia:

1) inconsistent understanding among the Cambodian people of the significance of educating and providing welfare to people with disabilities,

2) difficulties in interpreting technical terms and concepts that do not exist in Cambodia,

3) 3)unestablished professional positions of people with disabilities and their supporters,

4) difficulties in identifying local leadership, and

5) difficulty in developing activities due to the closed nature of relationships. The interviews in this study do not only highlight the above issues

in case studies, but also provides successful examples of how to solve these problems. The findings will be useful in planning and developing future

support for the education and welfare of people with disabilities in Cambodia.

Keywords: Cambodia; Education and welfare for people with disabilities

Introduction

Due mainly to historical traumas, disability policies in Cambodia have lagged behind. Cambodia’s economic condition was devastated by the Khmer Rouge regime in the late 1970s and the subsequent civil war that followed. When the domestic situation finally became relatively stable in 1990s, the country gave top priority to policies aimed at strengthening its economic power [1]. Cambodia has gradually achieved economic growth with support from abroad and improving education and welfare has become its next policy step. In particular, policies for people with disabilities have become an urgent priority, following the ratification of the International Convention on the Rights of People with disabilities in 2012. The Cambodian government has set the goal of improving the rights of people with disabilities to international standards, under the slogan of realizing social participation and inclusive education for people with disabilities.

However, policies of education and welfare for people with disabilities are not progressing consistently [1]. The Cambodian government is dependent on international economic aid, which directs the country’s diplomatic policy toward international cooperation and commitment [2]. As a result, while Cambodia’s constitution and government policies both set forth noble ideological goals, in reality, concrete policy initiatives have not kept pace with these goals. In addition to the limited financial resources of the Cambodian government, other factors have delayed development of policies for people with disabilities: discriminatory Buddhist ideology toward people with disabilities, [1] environmental issues including a lack of transportation for people with disabilities and their families, [1] and human resource issues including the lack of experts and professionals in special support education and welfare practices [3].

In light of these points, we believe that active supports, such as teaching practical knowledge from abroad and fostering the development of local experts will be effective in developing education and welfare policies for people with disabilities in Cambodia. In this study, interviews were conducted with three individuals involved in education and welfare support for people with disabilities in Cambodia in order to collect the interviewees’ empirical findings. In addition, the interviewees were asked about the difficulties in providing education or welfare support for people with disabilities in Cambodia, with the aim of discovering knowledge that could be used to implement more effective means of support in Cambodia in the future.

Case Presentation

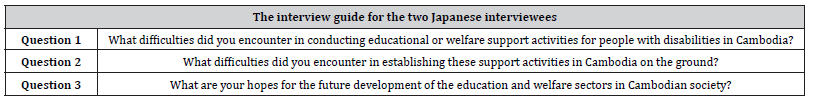

In this study, case study interviews were conducted with practitioners of educational and welfare support in Cambodia. Of the three interviewees, two are Japanese nationals, one living in Japan and one in Cambodia; the other interviewee is a Cambodian national living in Cambodia. Although the three interviewees shared a common goal of providing educational and welfare support to people with disabilities in Cambodia, their nationalities, upbringing cultures, and life circumstances were different from each other. These differences showcase the nature of support for Cambodia from diverse perspectives. The interviewees who cooperated in this study wished to use their names in the record for the purpose of expanding their own future activities and future references. The interview guide for the two Japanese interviewees consisted of the three items shown in Table 1.

Table 1:

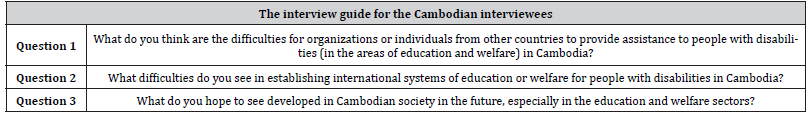

The Cambodian interviewee is in a different position in practical activities than the Japanese interviewees, as he accepts support groups from other countries and provides collaborative support for local development. Therefore, in order to clarify the difficulties of support from other countries– the main purpose of this study– we created an interview guide with different wording from that of the Japanese interviewees and conducted interviews in the three categories shown in Table 2.

Table 2:

Case 1 (Through support activities for welfare of the people with disabilities in Cambodia)

Interviewee:Mr. Koji Nakano (“Mr. Nakano”)

Nationality:Japanese

Place of residence:Japan

Affiliation:Representative of MABA, Mind and Body Development Consulting School MABA

Activities: Mr. Nakano specializes in practicing the Dohsa-hou/ Movement therapy, a development education technique developed in Japan to foster movement control in children with disabilities, and has started his own welfare service centering on the Dousahou. Since 2010, he has been working with the National Borei for Infant and children (“NBIC”), a residential facility for children with disabilities in the Cambodian capital city of Phnom Penh, to provide support activities for children with physical disabilities and training for facility staff. NBIC has been conducting support activities for children with physical disabilities and providing training for facility staff.

Interview Guide Question 1: What difficulties did you encounter in conducting educational or welfare support activities for people with disabilities in Cambodia?

When we initially started our activities in Cambodia, there was no concept of developing the abilities of people with disabilities. To me, it seemed that people with disabilities were perceived as “poor people who couldn’t do anything,” and the way of support was in family members and caregivers doing everything for the person. To develop the abilities of people with disabilities, it is important to increase the number of things they can do by themselves. To this end, it was difficult to instill in the local staff an understanding of how to encourage people with disabilities to try and accomplish things independently on their own.

To address the above difficulties, it was effective to have the participants actually experience how people with disabilities change and grow for the better through practice in case studies, rather than explaining didactically or through other forms of lectures. The NBIC staff I have worked with did not have as many academic opportunities, and some were illiterate. Therefore, I think that case practice was easier for them to understand rather than learning the ideas academically.

Interview Guide Question 2: What difficulties did you encounter in establishing support activities in Cambodia on the ground?

One of the biggest difficulties was the language barrier. In the beginning, we Japanese and the local staff communicated in poor English. However, this did not allow us to fully communicate with each other, nor could we fully understand each other. We were able to work with a Khmer, Cambodian native language interpreter who was fluent in Japanese, and we were able to communicate with each other in our native languages, which enabled us to communicate more fully than ever before. The introduction of a reliable interpreter was very significant for our activities.

Local leaders are also important for the establishment of the program. Since we only visit Cambodia twice a year from Japan, we need people who can consistently teach and practice the Dohsahou techniques locally. NBIC has a person who has obtained a supervisor certification of Dohsa-hou recognized by a Japanese academic organization and manages the practice of Dohsa-hou within NBIC. In order to meet such human resource demands, longterm and continuous activities are important, not just in a short period of time in a single year.

Interview Guide Question 3: What are your hopes for the future development of the education and welfare sectors in Cambodian society?

I think that Cambodia’s education and welfare systems for people with disabilities will be developed more and more in the future. In such a situation, what I hope is that the concept of rehabilitation and education for people with disabilities will become common knowledge among the people. I also hope that the way of involvement that nurtures the spontaneity and selfexpression of people with disabilities will permeate the country. In order to nurture the spontaneity and self-expression of people with disabilities, we must elicit their willingness and provide them with opportunities to make their own decisions and assert themselves. It is not that people with disabilities are incapable of doing anything, but that it is important for us, the supporters, to elicit their latent abilities. We hope that this way of thinking will permeate Cambodia.

Case 2 (Through support activities for welfare of the people with disabilities in Cambodia)

Interviewee: Kazuhiko Mamata (“Mr. Mamata”)

Nationality: Japan

Place of residence: Cambodia (Phnom Penh)

Affiliation: Visiting Lecturer, Faculty of Education, Royal University of Phnom Penh and Part-time Lecturer, Department of Japanese, Faculty of Foreign Languages

Activities: Mr. Mamata was born in Japan, graduated from a Japanese educational program. Since then, he has worked as a teacher at a school for the blind. In 2009, he visited Cambodia for the first time and visited the School for the Blind and the Deaf in Phnom Penh; from 2010 to 2013, he worked at Special Needs Education Research Center, University of Tsukuba and visited schools and related facilities for special needs education in Cambodia. From 2011 to 2012, he was a visiting professor at the Faculty of Social Sciences, Royal University of Phnom Penh, conducting research on special needs education. He married a Cambodian woman in 2011 and moved to Phnom Penh, Cambodia after his retirement in 2016. Currently, as a visiting lecturer at the Faculty of Education, Royal University of Phnom Penh, he conducts surveys, research, and supports science education and special needs education, while also giving the first special lecture on special needs education at the university

Interview Guide Question 1: What difficulties did you encounter in conducting educational or welfare support activities for people with disabilities in Cambodia?

In my experience, I found it difficult to understand the needs of the Cambodians. Perhaps because of the lack of school supplies in Cambodia, there is a tendency to ask for support in the form of supplies. I think that we should not only provide goods, but also training on how to use the goods, such as teaching methods. I approached the local staff to offer both supplies and training, but I did not receive positive reactions before I moved to Cambodia. In addition, Cambodians tend to have closed relationships, which is influenced by the historical trauma and mistrust created by the massacres and civil wars. So, in a sense, they may not have accepted me, a stranger, even if I had tried to provide some support from the outside. I currently live in Cambodia as a university faculty member and have a Cambodian wife. My wife is also a university faculty member and has contacts with government officials. As this position and profile may be credible, I have been able to provide assistance at various sites more than when I was in Japan. Currently, we are providing support for the provision of projectors to schools, and along with this, we also provide training for teachers and teach them how to use projectors in the classroom.

Interview Guide Question 2: What difficulties did you encounter in establishing these support activities in Cambodia on the ground? Establishing support requires leaders to promote activities within the local community. It is difficult to find people who can take on these leadership roles. In Cambodia, many people are still struggling to make a living for themselves. Therefore, there are not many people who are capable of taking meaningful action to change society for the better. In a sense, the stability of one’s own life is more important than that of society. Of course, there are those whose lives are affluent and powerful, but such people are more likely to work hard for themselves and their kin. Therefore, it is difficult to find individuals who can throw themselves into social development. Of course, it is not that the people I am referring to do not exist in Cambodia. It means that there are few opportunities, and it is important to engage in activities over a long span of time in order to meet them. I believe that through activities over a long span of time, human networks will gradually expand, leading to encounters with individuals who will function to establish themselves in the local community.

Another difficulty is the language barrier. To settle in, it is necessary to promote linguistic understanding locally. For this purpose, it is important to have interpreters who can translate each other’s native language well. In addition, technical terms that are commonly used in other countries, including Japan, may not be found in Cambodia. In such cases, interpreting is more difficult. A good interpreter will repeatedly confirm the meaning of what is said. They do not just randomly interpret, but actively communicate with us when they do not understand something, such as “I don’t understand,” or “I would like you to explain this term in more detail. If the interpreter interprets in Khmer with a proper understanding in their own way, the Cambodian side will have an absolutely better understanding. I teach Japanese at the Japanese language department of Phnom Penh University, and I am in contact with graduates who are interpreters, but it is difficult to find people who can provide the kind of interpretation in this way.

Interview Guide Question 3: What are your hopes for the future development of the education and welfare sectors in Cambodian society?

I think the first step is to have more budget allocated from the government. The other important thing is to train specialists. It is important to establish training courses for teachers of specialneeds schools at universities and other institutions, and to open more training courses for social workers in the field of welfare at universities and other institutions, as there are currently only three training courses for social workers in the field of welfare. They will be part of the government’s budget allocation and institutional reforms in Cambodia. Even if experts are trained, they need to be paid a salary and have a place to work so that they can earn a living. In Cambodia, such a system and environment have not yet been established, so it is hoped that they will be developed in the future.

Case Study 3 (Observing support from other countries from the standpoint of the Cambodian people)

Interviewee: Samith Mey (“Mr. Samith”)

Nationality: Cambodian

Place of Residence: Cambodia (Phnom Penh City)

Affiliation: Representative of Phnom Penh Center For Independent Living (PPCIL http://www.ppcil.org/)

Activity History: Mr. Smith was born with a physical disability of the lower limbs due to polio. When he studied abroad in Japan, he realized the importance of social participation for people with disabilities. After returning to Cambodia, he entered the Royal University of Phnom Penh and after graduating, established a center to support the independence of people with disabilities. He is working with support groups in other countries as well to realize a society in which people with disabilities can live independently in Cambodia.

Interview Guide Question 1: What do you think are the difficulties for organizations or individuals from other countries to provide assistance to people with disabilities (in the areas of education and welfare) in Cambodia?

After all, the problem of Cambodian people’s awareness of people with disabilities is significant. Although the Cambodian government and the people of Cambodia advocate the importance of social participation for people with disabilities, each individual citizen still does not fully understand the importance of social participation for people with disabilities. Many people do not understand the importance of educating people with disabilities and making them independent. There are many people who think that educating people with disabilities is not worth anything. In reality, there are still many poor people in Cambodia, so even if there are people with disabilities in their own families, many of them cannot afford to spend time and effort on their education.

Interview Guide Question 2: What difficulties do you see in establishing international systems of education or welfare for people with disabilities in Cambodia?

The key to establishing support is how well it works as a business, or how much benefits it will bring. In other words, how much their lives will be enriched. In Cambodia, there is a lack of education and access to welfare systems for people with disabilities to participate in society, and a lack of human resources to run such systems. How can the participation of people with disabilities in society enrich their lives, their families, and other related people? If the establishment of such a business can be realized, I believe that system of practice from abroad can be used to promote progress. However, it is difficult to imagine that such a system will be developed all at once. Therefore, it would be appreciated if the support from overseas is not for a short period of time, such as a single year, but as a continuous long-term activity for about ten years. Ten years will provide a place for people with disabilities to work and for those who support them to work. Once the workplaces are established, Cambodians will make effort to work there, and the significance of education for people with disabilities will be found.

Interview Guide Question 3: What do you hope to see developed in Cambodian society in the future, especially in the education and welfare sectors?

Regarding education, inclusive education for people with disabilities is important. I hope to see a society where people with disabilities can attend school and receive education together. In order to achieve this, it is necessary to support the transportation of people with disabilities to and from school, and it is necessary to promote the use of caregivers and welfare vehicles. In particular, there is no system in Cambodia to train caregivers, so it is hoped that the training system will be put in place in the future. Of course, the development of the above system will require the establishment of a business, and this will be realized only after securing salaries and workplaces for caregivers.

Discussion

The interviews in this study clearly demonstrated the difficulties in developing education and welfare practices for people with disabilities in Cambodia.

1) Inconsistent understanding among the Cambodian people

of the significance of educating and providing welfare to people

with disabilities

It was suggested that the philosophy and significance of

educating people with disabilities and realizing their participation

in society may not be fully understood at the national level in

Cambodia, which could make it difficult to develop support practices

from abroad. This may be due to the view of disability based on the

Theravada Buddhist ideology widely practiced in Cambodia, Added

the implication that people with disabilities related to karma have a

pitiful belief because they are far from Nirvana. Furthermore, a lack

of human capital, including specialists in education and welfare for

people with disabilities. Under these circumstances, Mr. Nakano

(Case 1) has provided the local staff with the actual experience

to learn that people can bring out their latent physical movement

abilities through Dohsa-hou, a movement development practice.

This has led the local staff to challenge societal mindset of people

with disability as “poor people who can’t do anything.”

2) Difficulties in interpreting technical terms and concepts

that do not exist in Cambodia

Mr. Nakano (Case 1) mentioned linguistic differences with local

staff as one of the main difficulties in developing and establishing

support activities and pointed out the difficulties caused by the

inability to communicate with each other in their native language.

This point was also mentioned by Mr. Mamada (Case 2), who

mentioned “language barriers” in using technical terms and ideas

that are not commonly used in Cambodia. He mentioned the

importance of “reliable interpreters” as an entity that can overcome

such difficulties. As for the specific image of an “interpreter,” as

described by Mr. Mamada (Case 2), he describes the attitude toward

to carefully check the meaning and nuance of terms and ideas

unfamiliar in Cambodia with the speaker, and to translate them into

Khmer after the interpreter themselves digest the meaning and

nuance. Mr. Mamada’s description should contribute to clarifying

the ideal interpreters’ image to overcome the language barrier.

3) Unestablished professional positions for people with

disabilities and their supporters; difficulties in identifying local

leadership

In the interviews with Mr. Mamada (Case 2) and Mr. Samith

(Case 3), they pointed out the social structure of Cambodia and

the resultant issues that make the practice of overseas assistance

difficult. First, people with disabilities are not guaranteed

opportunities and places to work. Secondly, along with the lack

of jobs and wages for those with disabilities, there are a lack of

training programs, job opportunities, and wages for professionals

to support those with disabilities. These two problems are current

issues for the Cambodian government, and it is necessary to address

these points in order to improve the social system in the future. In

addition to watching over the Cambodian government’s efforts to

develop the system on its own, it is believed that active support

from other countries, such as the transfer of effective knowledge,

will accelerate the development of the above-mentioned system..

The interviews also indicated that it is difficult for a country’s systems to change drastically in a short period of time and that long-term, continuous support is required. The interviews indicated that long-term and continuous support activities will lead to opportunities to the advantage and change of long-term support is not to meet Cambodian people with leadership qualities, but to be able to work on leadership development in the long term.

4) Difficulty in developing activities due to the closed nature

of relationships

In the interview with Mr. Mamada (Case 2), the closed nature

of relationships in Cambodia was pointed out, and he described

his experience of difficulties in developing support activities under

these social structures. The closed nature of relations in Cambodia

has been pointed out in other literature. In Cambodia, in the midst

of the massacres by the Khmer Rouge regime and the subsequent

civil war, perpetrators and victims were forced to coexist in the

same space. Under such circumstances, Cambodian citizens have

not been able to create local communities where they can trust

each other, and closed relationships have become a habit [4]. It

is also pointed out that in Cambodia, hierarchical relationships

based on power and social status are fixed, making it difficult to

develop activities such as the free exchange of opinions [5]. It

is also pointed out that such vertical hierarchical relationships

interrupt horizontal connections. In an interview with Mr. Mamada

(Case 2), he mentioned that his relationship with his wife, who has

connections with government officials and administrative officials

in Cambodia’s social structure, functioned as an opportunity to

approach the closed relationships in Cambodia. This point indicates

that in developing assistance in Cambodia, it is important to assess

the structure of relationships around the site of assistance and to

consider what paths to attempt to approach the site.

Acknowledgment

We would like to express our sincere appreciation to the three interviewees for cooperating in the interviews for this study. This research was supported by a Japanese Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT) Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (20K14065).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Jonsson K (2019) CRPD in Cambodia - Effectiveness of Inclusion through Affirmative Action in Employment. Lund University Libraries.

- Yotsumoto K (2009) Chapter 4: Disability and Development in Cambodia. In: Kobayashi, M. [Editor], Disabled People and the Law in Developing Countries: A Perspective on the Establishment of Legal Rights" Research Report. Institute of Developing Economies.

- Harada S (2021) The current state of Cambodian society through the life stories of people with disabilities. Community Caring, 23(4): 65-69.

- Makino F (2020) CAMBODIA the Space of Coexistence Memorializations, Negative Legacies and Communities. Shunpushya, Yokohama, Japan.

- Eda E (2019). Resident Participation in School Management in Cambodia. Mineruva, Kyoto, Japan.

-

Shinnosuke Harada, Sumire Sato, Anna Ueda. Difficulties in Providing International Support for People with Disabilities in Cambodia. Curr Tr Clin & Med Sci. 3(2): 2022. CTCMS.MS.ID.000557.

-

History of medicine, Neighborhood, Mysterious sickness, Mineral, Planet, Solar system, Uranium, Potassium sulfate, Radium, Comparison, Measurements, Self-luminous, Environmental problem, Belgium

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.