Mini Review

Mini Review

2020 FDA Drug Approvals: Does Investment in More and Larger Trials Result in Higher Price?

Amanda Jeanette Koong and Robert M Kaplan*

Clinical Excellence Research Center, Stanford University School of Medicine, USA

Robert M Kaplan, Clinical Excellence Research Center, Stanford University School of Medicine, USA.

Received Date: November 18, 2021; Published Date: December 14, 2021

Abstract

Keywords: FDA; Drug Pricing; 21st Century Cures Act; Research Methods

Introduction

Since the passage of the 21st Century Cures Act in 2016, The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has applied less stringent guidelines for new drug evaluations [1], resulting in a decreasing number of RCTs before approval [2]. The 21st Century Cures Act, passed in 2016, was designed to allow the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to accelerate the approval of pharmaceutical products, by decreasing usage of morbidity and and mortality outcomes and increasing use of surrogate biomarker measures. In addition, it acknowledged a wider range of study designs, including alternatives to multiple randomized clinical trials (RCTs).

The FDA began reporting approvals of new molecular entities (NMEs) in 1940. Before 2016, an average of 22.1 NMEs were approved each year with modest average annual increase of 0.19/ year. In the three years following the approval of the Act, an average of 51.5 NMEs have been approved each year, exceeding projections from previous trend lines [2]. This report concentrates on the 53 novel drugs approved by the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research in 2020. We explored whether the cost saved during drug development, as indicated by fewer RCTs and fewer participants per trial [3], resulted in decreased price for consumers.

Method

Using the FDA website [4], we examined all novel drug approvals during the 2020 calendar year. We excluded 2 products used for diagnostic tests, 1 product was approved without clinical trial evidence, and 4 products for which insufficient data were publicly available. For each approval, we retrieved all clinical trials listed in Clinicaltrials.gov under the active ingredient and the indication. In three cases, ClinicalTrials.gov did not show any trials associated with the active ingredient. In these cases, we traced the trials listed in the approval to identify an alternative name for the active ingredient. We then totaled the trials used for the approval, the trials registered by the calendar year of the approval, the completed trials and the RCTs registered in clinicaltrials.gov.

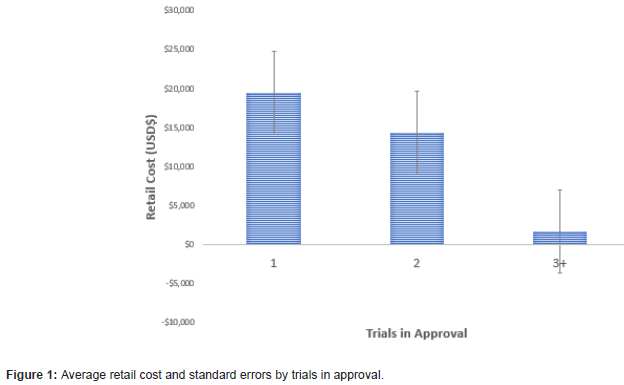

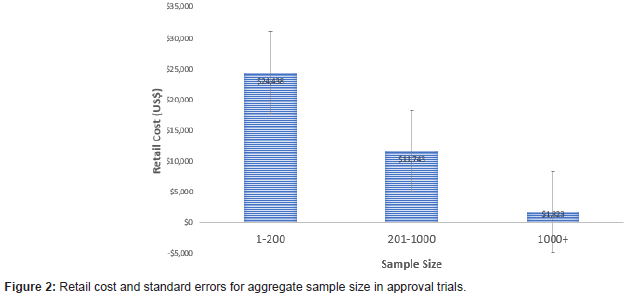

Using Micromedex IBM Redbook [5], we retrieved average retail cost of one course of treatment, or one package of pills. Costs were standardized by comparing the charge for a one-month supply. Means, standard deviations and confidence intervals were calculated for products that were approved on the basis of 1 (N=22), 2 (N=12), 3 or more (N=7) RCTs. For the number of trial participants, we used categories of small <200 (N=17), medium 201-1000 (N=17), and large >1001 (N=9) trials.

Results

There was a negative linear association between the number of trials used in the approval and the average retail cost of the medication (t=2.41, p=.025) (Figures 1,2). The average cost of the 21 products approved on the basis of one trial was $19,504 (SD $34,739), in contrast to $1650 (SD $1919) for the 7 products approved on the basis of 3 or more trials. The 3+ category included two outliers with 28 and 49 trials. In each of these cases, the average cost/person for the approved drugs was less than $1000. A similar trend showed increased cost as the number of trial participants decreased (F 4/42=2.70, p=.045). The average cost of products evaluated using less than 200 subjects was $24,438 (SD $38,906), in contrast to $1,823 (SD $2,694) for products evaluated using more than 1000 subjects.

Discussion

Both the number of trials and the number of trial participants are inversely related to the price of medications approved by the FDA in 2020. This pattern is opposite to the expectation that larger investment in more trials leads to higher priced products. We recognize that drug pricing includes many factors beyond the costs of trials. For example, there is only a small probability that any one product will reach the market and pricing may reflect costs devoted to failed efforts within a broader portfolio. Additionally, for rare diseases, the development costs are high, while the rarity of the conditions make small sample sizes likely. The 2020 analysis also included Remdesivir, a product that was given Emergency Use Authorization and early approval on the basis of limited trial data because of the urgent desire to find a therapeutic agent to address the COVID-19 epidemic. Despite these nuances, our results appear consistent with a variety of reports suggesting that pricing of pharmaceutical products is unrelated to drug development costs [3].

Limitations of our study include a relatively small number of drugs analyzed. Further, the global COVID-19 pandemic clearly made 2020 an unusual year, perhaps resulting in increased scrutiny by the FDA. Because of these limitations, it is important to interpret the results with caution. However, we believe that approval of the most expensive pharmaceutical products on the basis of fewer studies and studies that include fewer participants deserves further attention.

Acknowledgment

None.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of Interest.

References

- Kaplan RM (2019) More Than Medicine: The Broken Promise of American Health. Harvard University Press.

- Darrow JJ, Avorn J, Kesselheim AS (2020) FDA Approval and Regulation of Pharmaceuticals, 1983-2018. JAMA 323(2): 164-176.

- Rawlins MD (2016) Cost, Effectiveness, and Value: How to Judge? JAMA 316(14): 1447-1448.

- (CDER) FaDACfDER (2021). Novel Drug Approvals for 2020. FDA. Accessed February.

- Micromedex IBM Redbook.

-

Amanda Jeanette Koong, Robert M Kaplan. 2020 FDA Drug Approvals: Does Investment in More and Larger Trials Result in Higher Price?. Curr Tr Clin & Med Sci. 2(5): 2021. CTCMS.MS.ID.000549.

-

Biomarker measures, Molecular entities, Clinical Trials, Treatment, Diseases, COVID-19 epidemic

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.