Research Article

Research Article

Urethral Calculi: Presentation, Evaluation and Management

Mukesh C Arya1*, Ajay Gandhi2, Ankur Singhal2, Mahesh Sonwal2 and Rakesh Maan2

1Professor and head, Department of urology, Sardar Patel medical college, Bikaner, Rajasthan, India

2Mch Senior Resident, Department of urology, Sardar Patel medical college, Bikaner, Rajasthan, India

Mukesh C Arya, Professor and head, Department of urology, Sardar Patel medical college, Bikaner, Rajasthan, India.

Received Date: September 09, 2020; Published Date: September 23, 2020

Abstract

Introduction: Urethral calculi constitutes about 1-2% of all calculi in developing countries. Such calculi are more common in males in comparison to females owing to their longer urethra. Herein, we present a series of 264 such calculi.

Material and methods: This is a retrospective study of 264 cases of urethral calculi from July 2013 and February 2019. Detailed history, physical and local examination (palpation of penile urethra and perineum including Digital rectal /Per Vaginal examination) was done. Investigations included urine analysis, culture and sensitivity, ultrasonography (USG) whole abdomen with the perineal region and X-ray pelvis. A retrograde urethrogram was performed if associated urethral pathology was suspected. Cystourethroscopy confirmed the diagnosis in all cases. Patients were analysed about their age, sex, presentation, anatomical site of stone at the time of presentation, and their subsequent management. Composition of urethral calculi was studied using Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR).

Results: A total of 264 patients with urethral calculi were analysed (250 males and 14 female). Most common age group was 21-40 years (46.8%). 203 (81.2%) of the calculi in the male patients were in the posterior urethra, 25 (10%) were in the penile/ bulbar urethra and 22(8.8%) in the fossa navicularis. The most common presenting symptom was dribbling & dysuria (70.45%). Radiological studies (X-ray pelvis and USG) showed stone in 85% of cases; Cystourethroscopy was diagnostic and discovered the stone in 15 % of additional cases. Size of stones varied from 1.2 to 2.5 cm. Most of the patients i.e. 190 (71.96 %) were treated with pushback cystolithotripsy (CLT).

Conclusion: Most urethral calculi in patients in developing countries originate from upper tract in contrast to the previous misconception that they originate in the bladder. Management of the urethral calculi varied according to the site, size and associated urethral pathology.

Keywords: Urethral calculus; anterior urethral calculi; pushback cystolithotripsy

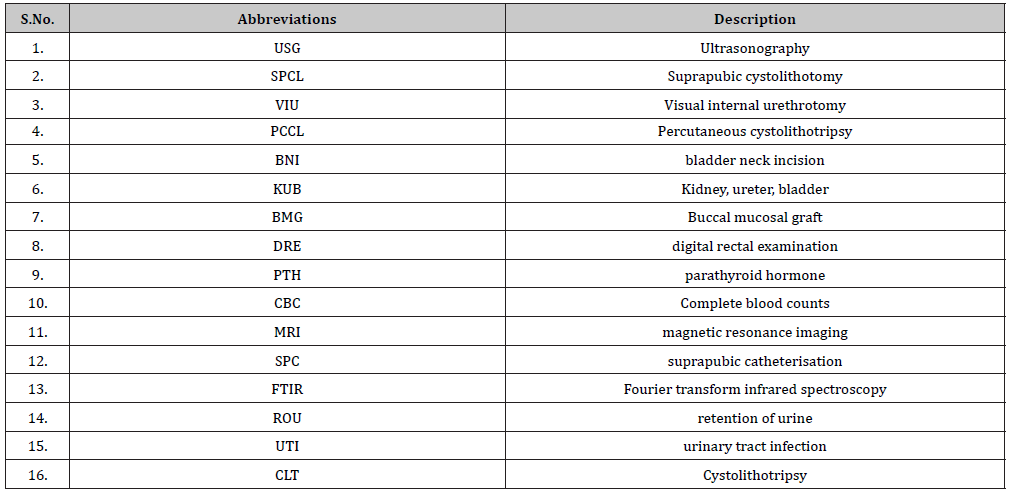

Abbreviations: Cystolithotripsy (CLT); Ultrasonography (USG); Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR)

Introduction

Urethral calculi are common in developing countries. There are only a few studies that have been conducted so far on these subsets of patients with very limited literature from developing countries. Urethral calculi are divided into primary which forms in urethra and secondary, which migrates from upper urinary tract. Primary urethral calculi are usually small and multiple, and secondary migratory calculi are usually large. Small calculus is commonly found in the anterior urethra and larger calculi usually occur in the posterior urethra. Primary urethral stones are generally composed of magnesium ammonium phosphate (struvite) or uric acid. Calcium oxalate and cystine stones originate from kidney. The causes of secondary stones are stricture, infection, and/or inflammation or within a poorly drained communicating cavity, with an obstruction, stagnation, acting as the predisposing factor.

Secondary or migratory stones are usually more common mainly comprising of calcium oxalate or citrate. Migratory stones are most often encountered in association with urethral stricture disease or other forms of urethral obstruction .The main symptoms are dribbling, dysuria, acute urinary retention, frequency, haematuria, interruption of the urinary stream, or a history of spontaneous passage of stone (such patients were excluded in our study). Retrograde manipulation into the urinary bladder followed by litholopaxy or lithotripsy is a suitable procedure for small urethral calculi. Anterior urethral calculi can be removed under local anaesthesia via endoscopy or ventral meatotomy.

Patients and Methods

This is a retrospective study of 264 patients presenting with urethral calculi from July 2013 and February 2019. A detailed urological history was taken along with physical and local examination including palpation of the urethra and digital rectal examination (DRE). Complete blood counts (CBC), serum biochemistry including serum urea and creatinine serum calcium, serum uric acid, serum parathyroid hormone (PTH), urine calcium creatinine ratio, urine analysis, urine culture and sensitivity, ultrasonography whole abdomen with perineal/scrotal region and x-ray pelvis were done. Intravenous urography (IVU) was done in cases with upper urinary tract calculi. A retrograde urethrogram was performed if associated urethral pathology was suspected. Cystourethroscopy was performed in all cases and confirmed the diagnosis. MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) was done in one female to depict relevant anatomy of the urethral diverticulum and associated stone. Urethral calculi were analysed about age, sex, presentation, the anatomical site at presentation, associated diseases, and management. Finally, the stone analysis was done using Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) to study the composition of urethral calculi.

Results

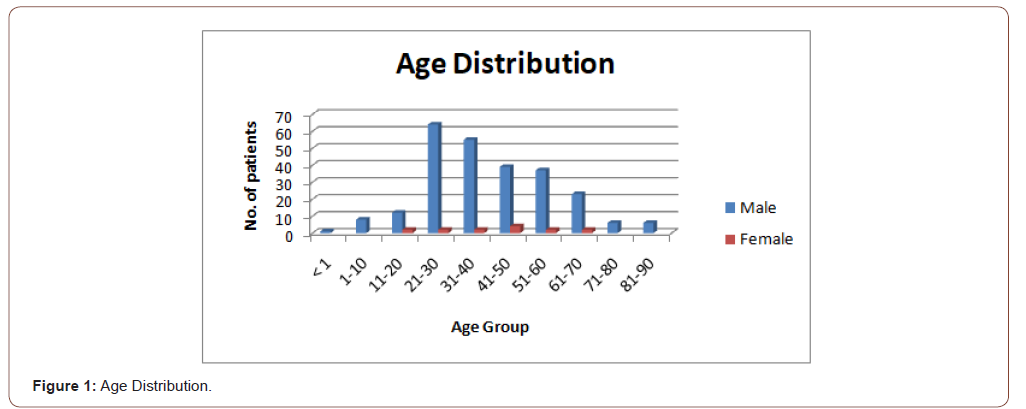

1. Age and sex: A total of 264 patients with urethral calculi were analysed (250 male and 14 female). Male to female ratio was 17.8: 1. Age ranged from 6 months to 86 years (Figure 1).

The maximum number of patient (46.6%) was in the 21-40 years of age group. Mean age was 52.7 years.

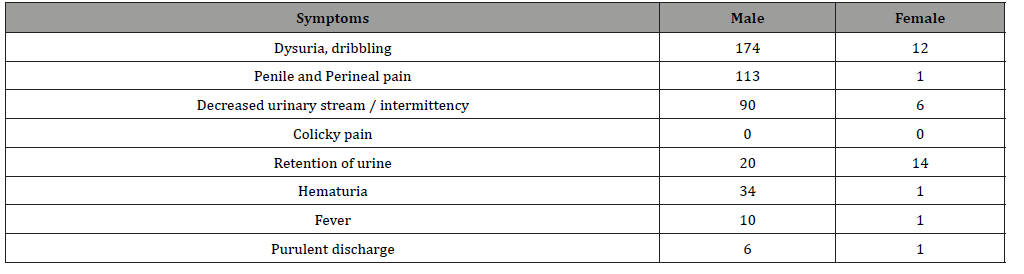

2. Presenting complaints: Most common presenting symptom was dribbling &dysuria (70.45 %) followed by penile& perineal pain (43.18%), decreased urinary stream & intermittency (36.36%), retention of urine and hematuria (12.87% each), fever (3.78%) and purulent discharge (2.27%) in these patients (Table 1).

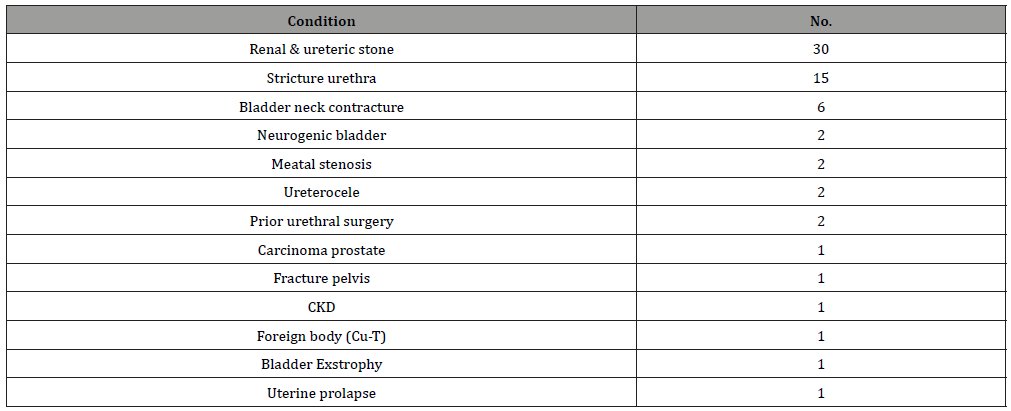

Out of these, 81 stones (30.68%). were palpable; one female (age 31years) had procidentia with a palpable stone in the prolapsed bladder. Twenty-nine (10.98%) had associated diseases of the lower urinary tract, the commonest being urethral stricture (15 patients). Seventy-four patients (28.03%) had a prior history of urolithiasis or surgery for the same (Table 2).

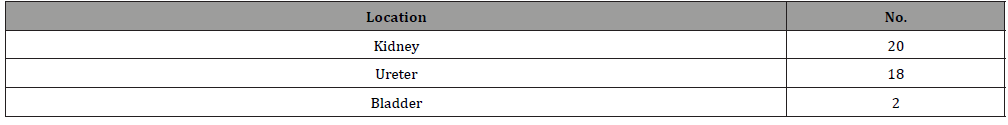

Associated upper urinary tract calculi were found in 30 cases. Out of which, 2 were in the bladder, 20 in kidney and 18 in ureter (Table: 3).

Table 1:Clinical presentation.

Table 2:Associated conditions.

Table 3:Associated urinary calculi (n=30).

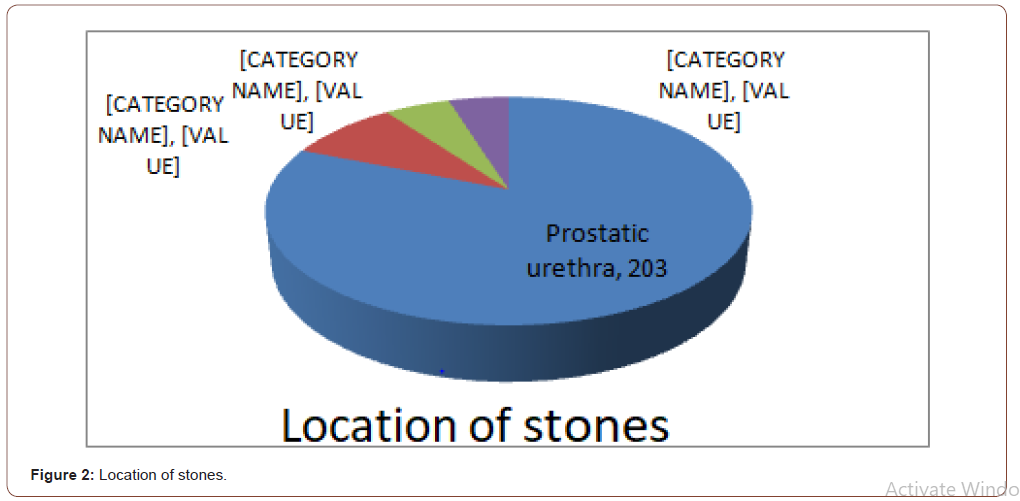

3. Location of stones: In male patients, the most common location was in the posterior urethra 203 (81.2%), 13 (5.2%) in the bulbar urethra, 12 (4.8%) in penile urethra and 22(8.8%) in the fossa navicularis (Figure 2).

All-female patients and 7.57% of male patients presented with retention of urine (ROU). In these patients, catheterisation was done; while in 28 cases where the attempt of catheterisation was unsuccessful suprapubic catheterisation (SPC) was done.

4. Urine culture: In only 18 cases, urine culture was positive. Majority of them (15) were positive for E. coli, two for klebsiella and one showed growth of pseudomonas.

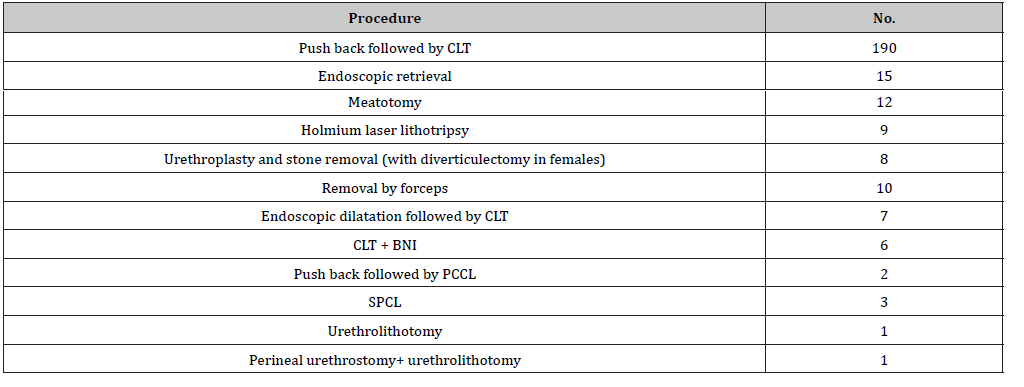

5. Management: One hundred fifty-one cases were operated under local anaesthesia, followed by 90 in spinal and 23 in general anaesthesia. Most of the patients i.e. 190 (71.96 %) were treated with pushback cystolithotripsy (CLT), 15 patients (5.68%) were treated with endoscopic retrieval, 12 patients (4.54%) were treated with meatotomy with the retrieval of stone. Larger stones impacted at meatus should be treated with meatotomy to prevent stricture. Holmium laser lithotripsy was done in nine patients of the pediatric age group using 6-7.5 F ureteroscope. Seven patients (2.64%) with urethral calculi and associated urethral strictures underwent visual internal urethrotomy or endoscopic dilatation initially; the stones were then pushed into the bladder and CLT was done. In the remaining eight patients (3.03%) urethrolithotomy & BMG onlay urethroplasty was done. Percutaneous cystolithotripsy (PCCL) done in 2 cases, perineal urethrostomy done in 1 case, CLT and bladder neck incision (BNI) done in 6 cases. Foley’s catheter was placed for 3-5 days after VIU/meatotomy, 3 weeks for onlay urethroplasty and for 2 weeks after diverticulectomy. Suprapubic cystolithotomy (SPCL) was done in 2 patients with neurogenic bladder and one patient with Exstrophy; these patients were put on CIC. One female had a diverticular stone which was treated with diverticulectomy and another female patient had associated uterine prolapse in whom sacral colpopexy was done (Table 4).

These patients were followed at 6 weeks and 3 months with symptomatology, uroflowmetry to detect stricture due to stone or transurethral surgery. Seven patients developed stricture in the bulbar urethra which was managed successfully with VIU. Twelve patients developed symptomatic urinary tract infection which was treated by culture-sensitive antibiotics.

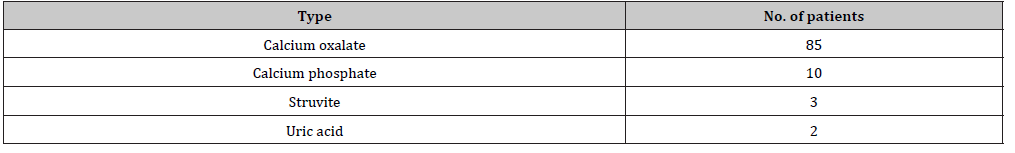

6. Stone analysis: Stone analysis was performed in 100 cases using FTIR of which mostly (85 cases) were mixed stone with calcium oxalate monohydrate as a primary component, calcium phosphate in 10, struvite in 3 and uric acid stone in 2 patients (Table 5).

7. Metabolic evaluation: Metabolic evaluation could be done only in 33 patients. Among these, fifteen patients had hypercalciuria. One patient had hyperparathyroidism and 1 had hyperuricemia; they were referred to an endocrinologist for further management (Tables 6,7).

Table 4:Treatment modalities.

Table 5:Type of stones (predominant component).

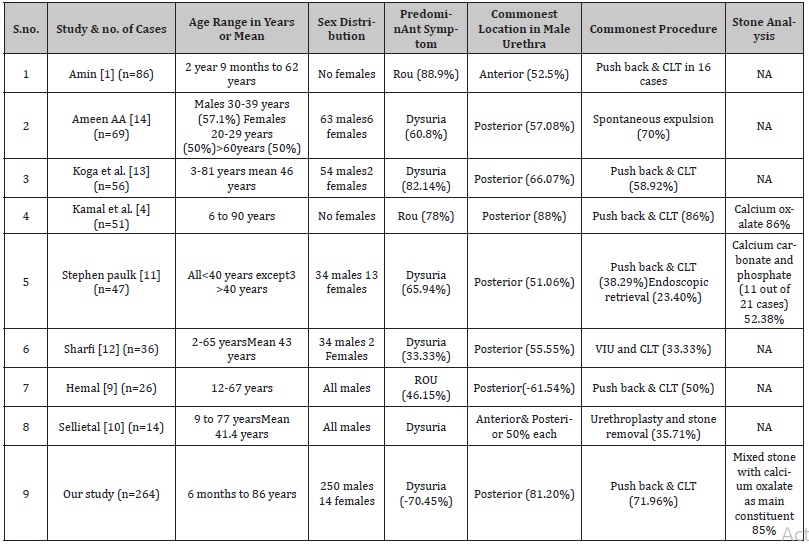

Table 6:Comparison of all studies.

Table 7:Abbreviations.

Discussion

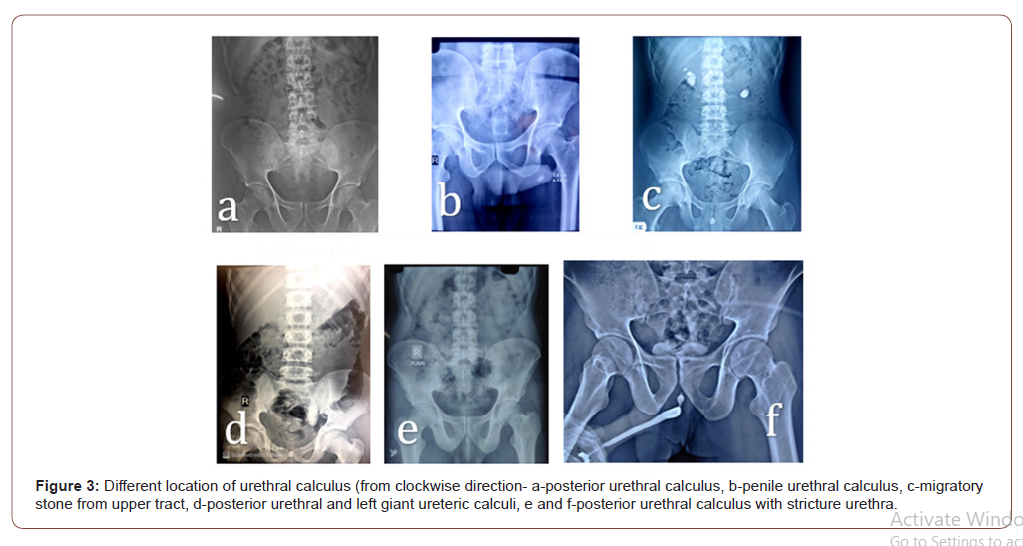

Calculi in the urethra is not uncommon in developing countries. From developing countries, only a few studies were focused on such patients. In our study, patient age ranged from 6 months to 86 years with a mean of 52.7 years. Most of the patients (46.8%) were in the age group of 21-40 years. The difference in age prevalence may be due to the differences in lifestyle, nutritional habits and environmental conditions. Mean age in other studies was 43 – 46 years12,13. The proportion of females was 14 (5.3%) in our study and only one had associated diverticular disease. This was in contrast with other studies in which all of the females with urethral calculi had urethral diverticulae11,12. Dysuria remains to be the commonest symptom in the range of 33.33 % to 82.14 % in different studies 9,11,12,14. Retention of urine was commonest occurrence in 46% - 89% of patients1,4,9. The most common presenting symptom in our series was dribbling & dysuria (70.45 %) followed by penile & perineal pain (43.18%), decreased urinary stream & intermittency (36.36%). In our study, ROU was present in 12.87% of cases only. Associated upper tract calculi were present in 32 - 33% of the patients1,2. This emphasizes the importance of evaluation for the upper urinary tract in patients with urethral calculi. In our series, upper tract stones were present in 11.36% (20 in kidney and 18 in the ureter). Posterior urethral location is commonest for urethral calculi as presented in various studies 4,9,12,13,14. This was in concordance with our study in which 81% of stones were in posterior urethra. However, few authors have reported anterior urethra to be the most common site (50- 63%)1,10 (Figure 3).

In our series majority of stone, 237 (89.77 %) could be treated by different types of endoscopic procedures similar to study of Kamal etal4 in which 86% undergone endoscopic procedures. This was in contrast of study to Ameen and colleagues14. They reported spontaneous passage in the majority (70%). We however, excluded such patients. Stone analysis was reported in a few studies with mixed stones and calcium oxalate monohydrate as a principal constituent in a majority in around 70-80% % 4,11. Similar were the results in our series. Other constituents were calcium phosphate, struvite and uric acid. This confirms that most of these stones are dropped ones from an upper tract in contrast to common belief previously that these stones originated in the bladder. Correction of urethral stricture and control of infection is vital to prevent a recurrence. Chemical composition helps us to take preventive measures. Management of the urethral calculi varies according to the site, size and associated urethral pathology. Retrograde manipulation into the urinary bladder, followed by litholopaxy, is a safe procedure for posterior urethral calculi provided that the manipulation is done endoscopically or by saline irrigation under direct vision. Irrigation expands the urethra and facilitates the passage of stone to the bladder. A urethral stricture can be dealt by visual internal urethrotomy before manipulating the calculus into the urinary bladder. Impacted, large irregular calculi or those in a urethral diverticulum are best removed through open exploration, external urethrotomy followed by excision and repair of the diverticulum. Extraction through the external meatus is suitable only for small, smooth calculi in the region of fossa navicularis. It should be done with great caution to prevent urethral mucosal injury. In two cases of ureterocele with stones, endoscopic incision of ureterocele with CLT was done. In one female, CuT migrated into bladder and formed calculus, dealt with endoscopically.

Conclusion

Most urethral calculi in patients in developing countries originate from upper tract in contrast to previous misconception that they originate in the bladder. Furthermore, urethral anatomical pathology does not seem to be a necessary condition for most such stones. In all patients who presented with lower urinary tract symptoms especially in younger age group, urethral stone should be kept in mind as differential diagnosis and X-ray KUB with pelvis is advisable in these patients.

Acknowledgment

None.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest.

References

- Amin HA (1973) Urethral calculi. Brit J Urol 45: 192.

- Shanmugam TV, Dhanapal V, Rajaraman T, Chandrasekar CP, Balashanmugam KP (2000) Giant urethral calculi. Hosp Med 61(8): 582.

- Usta MF, Baykara M, Erdoğru T, Köksal IT (2005) Idiopathic prostatic giant calculi in a young male patient. Int Urol Nephrol 37(2): 295-297.

- Kamal BA, Anikwe RM, Darawani H, Hashish M, Taha SA (2004) Urethral calculi: presentation and management. BJU Int 93(4): 549-552.

- Lows OS, Kirw JJ (1956) Clinical urology, Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins Company.

- Kaplan M, Atakan IH, Kaya E, Aktoz T, Inci O (2006) Giant prostatic urethral calculus associated with urethrocutaneous fistula. Int J Urol 13(5): 643–644.

- McCall RW, Bann MP (1992) Lower urinary tract calculi and calcifications. In: Pollak HM, editor. Clinical urography. Saunders: USA pp.1904–1915.

- Wollin TA, Singal RK, Whelan T, Dicecco R, Razvi HA, et al. (1999) Percutaneous suprapubic cystolithotripsy for treatment of large bladder calculi. J Endourol 13(10): 739-744.

- Hemal AK, Sharma SK (1991) Male Urethral. Calculi Urol Int 46: 334-337.

- Selli C, Barbagli G, Carini M, Lenzi R, Masini G (1984) Treatment of male urethral calculi. J Urol 132(1): 37-39.

- Paulk SC, Khan AU, Malek RS (1976) Urethral calculi. J Urol 116: 436-439.

- Sharfi AR (1989) Complicated male urethral strictures: Presentation and management. Int Urol Nephrol 21(5): 491-497.

- Koga S, Arakaki Y, Matsuoka M (1990) Urethral calculi. Br J Urol 65: 288-289.

- Ali Abdulqader Ameen, Hrair Haik Kegham, Ali Hussein Abid (2017) Evaluation and management of urethral calculi. Int Surg J 4(8): 2392-2396.

-

Mukesh C Arya, Ajay Gandhi, Ankur Singhal, Mahesh Sonwal and Rakesh Maan. Urethral Calculi: Presentation, Evaluation and Management. Annal Urol & Nephrol. 2(2): 2020. AUN.MS.ID.000532.

-

Urethral calculus, Anterior urethral calculi, Pushback cystolithotripsy, Magnesium ammonium phosphate, Uric acid, Calcium oxalate, Cystine stones originate

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.