Research Article

Research Article

Unexplained Recurrent Nocturnal Urethral Bleeding: An Unusual Presentation of Penile Fracture

Mukesh Chandra Arya*1, Vivek Vasudev2, Yogendra Shyoran2, Abhiyutthan Singh Jadon2, Ajay Gandhi2 and Ankur Singhal2

1Professor and Head, Department of urology, Sardar Patel medical college, Bikaner, Rajasthan, India

2Department of urology, Sardar Patel medical college, Bikaner, Rajasthan, India

Mukesh C Arya, Professor and Head, Department of urology, Sardar Patel medical college, Bikaner, Rajasthan, India.

Received Date: September 12, 2020; Published Date: October 05, 2020

Abstract

Introduction: Penile fracture is an emergency condition. Common presentation is classical history of trauma to erect penis followed by detumescence, penile swelling, ecchymosis and discoloration. Management is primarily surgical. We report our experience of such cases including a subgroup of patients with unexplained recurrent nocturnal urethral bleed without penile swelling and normal voiding.

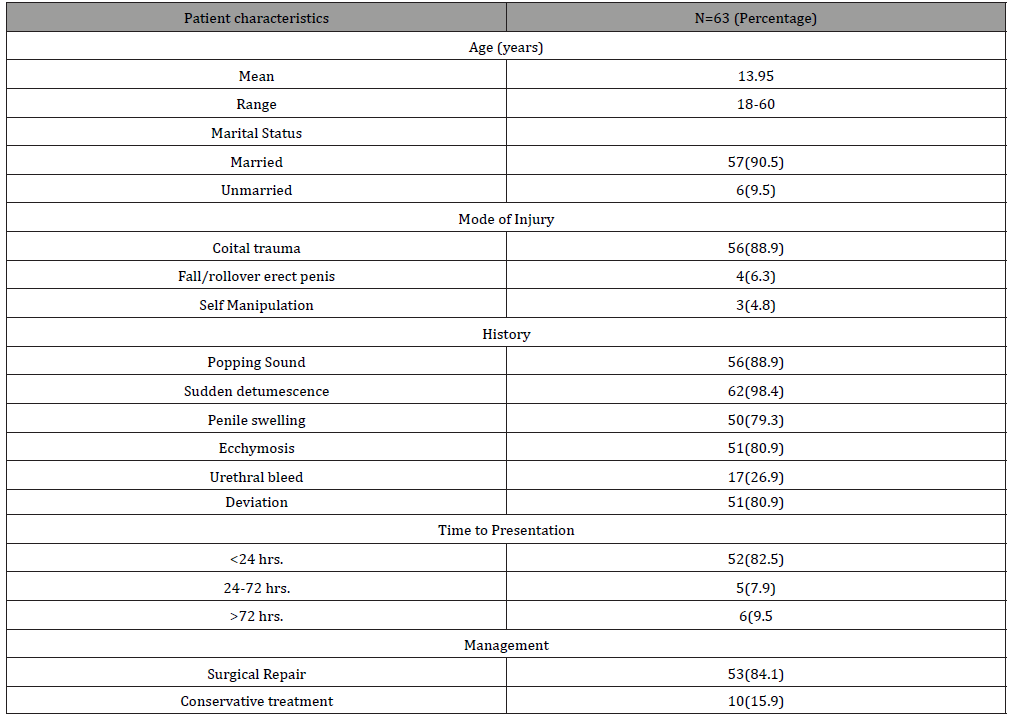

Material and methods: This a retrospective study performed at our institution. Records of penile fracture cases managed over last 6 years were reviewed. Total of 63 patients were managed either by surgical (53 patients) or conservative (10 patients) approach. Sexual outcomes were measured with abbreviated International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF 5) questionnaire and compared with preoperative scores.

Results: Most common aetiology was coital trauma, seen in 88.9 % of patients. Mean age was 34.95 years. Urethral injury was present in 5 (9.4%) patients in the surgical group. Most common site of injury was ventrolateral {32 (60.4%)} over proximal shaft {49 (92.5%)}. Mean follow up was 19.27 months ranging from 6 to 41 months. Erectile function was preserved (no deterioration in IIEF 5 category) in 96.3 % and 100% of patients from surgical and conservative groups.

Conclusion: Unexplained recurrent nocturnal urethral bleed as a presentation of penile fracture, should be kept in mind. Such peculiar presentation, to our knowledge, has not been reported in literature. This subgroup of patients can be managed conservatively with good sexual and voiding functional outcome.

Keywords: Nocturnal urethral bleed; Penile fracture; Conservative management; Erectile dysfunction

Abbreviations: IIEF: International Index of Erectile Function; ED: Erectile Dysfunction

Introduction

Penile fracture is an emergency urological condition defined as rupture of tunica albuginea of corpora cavernosa because of trauma to erect penis as a result of sudden increase in intra-corporeal pressure. Typically it occurs during coitus when the phallus strikes against the pubis or perineum of partner producing a buckling injury [1]. It can also occur during self-manipulation, rolling over or falling onto erect penis or due to practice of “taqaandan” [2,3]. Patient usually describes a “cracking” or “popping” sound followed by detumescence, pain, swelling and discoloration of penile shaft. If the Buck’s fascia remains intact the hematoma is limited to shaft. If it is also disrupted the hematoma can reach to perineum and suprapubic area. Diagnosis is clinical and management is primarily surgical. We report our experience of managing penile fracture cases over last 6 years with especial impression upon a group of patients having an unusual clinical presentation with unexplained recurrent nocturnal urethral bleeding without penile swelling.

Materials and Methods

Introduction

This is a retrospective analytical study of cases of penile fracture treated at our institution from August 2014 to September 2019. Patients with penile fracture with diagnosis based on classical history of trauma on erect penis followed by sudden detumescence were included. They underwent routine hematology and biochemistry investigations. Pretrauma erectile function was documented using IIEF 5 questionnaire. They were managed either with surgery (N=53) or conservative treatment (N=10).Patients with minimum 6 months follow up were included. Patients with false penile fracture due to rupture of dorsal vein were excluded. Dorsal venous injury could be differentiated from penile fracture as the former does not lead to sudden detumescence, patient can cohabitate further and the site of hematoma being limited to dorsal surface of penis. Data was retrieved from institutional registry of penile fracture patients. Diagnosis of the condition was virtually clinical. Institutional protocol is of emergency repair of such cases without any delay. Conservative management was opted in a special subgroup of patients who presented with unexplained recurrent nocturnal urethral bleeding and either not diagnosed or misdiagnosed and treated for hematuria of unknown cause before being referred to us. This treatment plan was based on shared decision making. On enquiring further these patients had classical history of sexual trauma with “popping” sound and sudden detumescence but no penile swelling. The temporal association of proper history with their symptoms helped us to clinch the diagnosis. Classically all of them had no penile swelling and were voiding well. To document tunical rupture in this subgroup, imaging studies were performed. Ultrasound of penis in 8 /10 cases confirmed the diagnosis. MRI documented it in the remaining 2 cases. Conservative management included compressive dressing, Foley catheterization, antibiotics, anti-inflammatory and antierotic drugs (conjugated estrogen 0.625 mg PO twice daily for 1 week). Many of them refused admission and were managed on outpatient basis. The catheter was kept for 7 days. The surgical management included penile exploration under anaesthesia by a circumcoronal incision, penile degloving, inspection of corporeal tear, repair with delayed absorbable sutures (using PDS 3-0 with knots buried inside) followed by repair of Buck’s fascia over it and circumcision at conclusion of procedure. Circumcoronal incision allowed survey of whole penile shaft and also avoided overlying suture lines with sound healing. Delayed absorbable suture provides ample time for corporeal and tunical tissue to heal without abnormal feeling of knot post operatively. If Bucks fascia is intact and exploration is being performed, one can reach the site of tunic tear only after incising the fascia. Foley catheter was kept and compressive dressing applied. Concomitant urethral repair was undertaken if found injured except in one case in which the repair was staged. Apart from postoperative antibiotics (third generation Cephalosporin and aminoglycoside), anti-inflammatory drugs all patients were given conjugated estrogen 0.625 mg PO twice daily for 1week to prevent erections and advise was given to refrain from sexual activity for 6 weeks. Patients who had not undergone urethral repair were discharged on post-operative day 2nd after removal of dressing and Foley catheter. Catheter was kept for 2 weeks if urethral repair was contemplated. Follow up included history for any voiding or sexual symptoms and local physical examination. Erectile function was assessed at 6 months with IIEF 5 score [4].

Result

Total of 63 patients were included in the study. Mean age was 34.95 years ranging from 18 to 60 years. Most common mode of injury was coital trauma in 88.9 % of patients. Presentation was in different combinations of “popping” sound, sudden detumescence, penile swelling, ecchymosis, deviation and urethral bleed (Table 1)

Table 1:Patient characteristics and history.

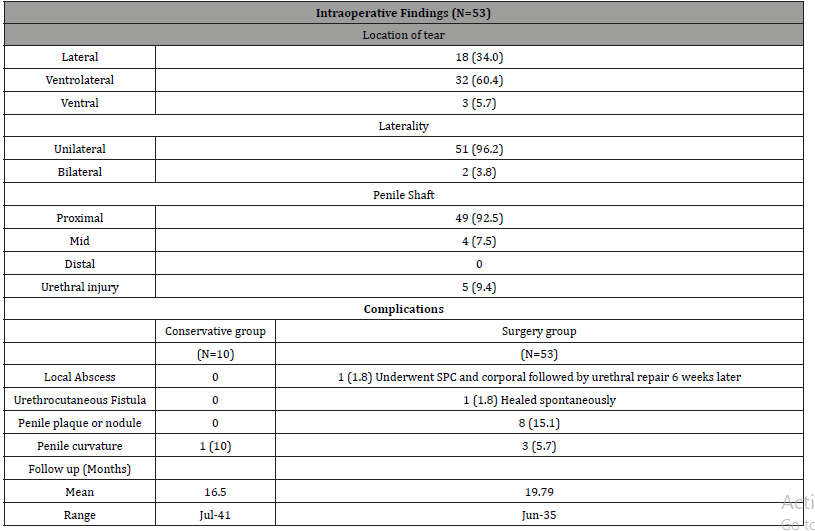

Table 2:Intra operative findings, post-operative complications and follow up.

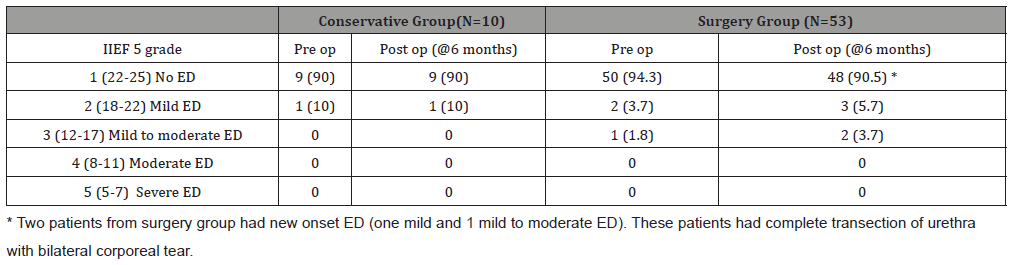

Table 3:Erectile function outcomes.

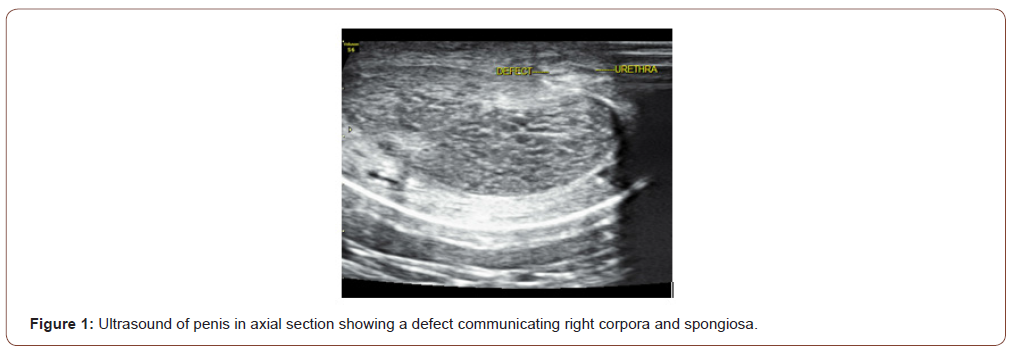

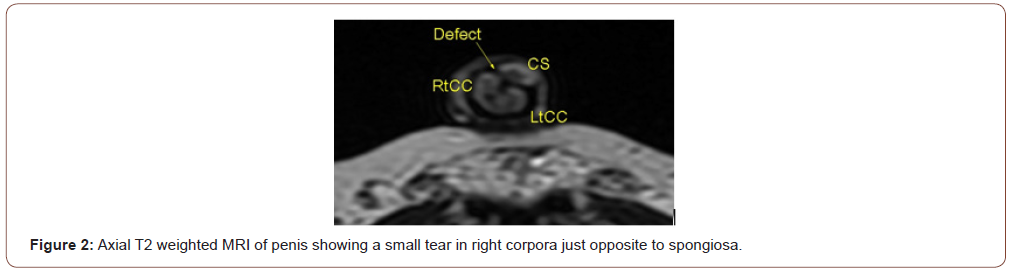

There was a peculiar group of 10 patients who had coital trauma followed by recurrent nocturnal urethral bleed without any symptom in daytime. They presented late to us and were treated elsewhere as UTI or hematuria but on enquiring into history all of them gave classical history of coital trauma. Ultrasound and/or MRI was done to confirm the diagnosis. The imaging revealed a tear of corpora cavernosa and overlying corpus spongiosum (Figure 1,2).

The proposed mechanism of such injury is a small corporal tear located just opposite to a spongiosal rent and intact Buck`s fascia. The intermittent nature of bleed was due to nocturnal erections opening the communication with corporal blood finding its way out through urethra. They found their undergarments full of blood in the morning when they woke up. As blood decompresses through urethra, penile swelling does not occur and they void clear urine during daytime. The operative findings, complications and follow up are presented in (Table 2).

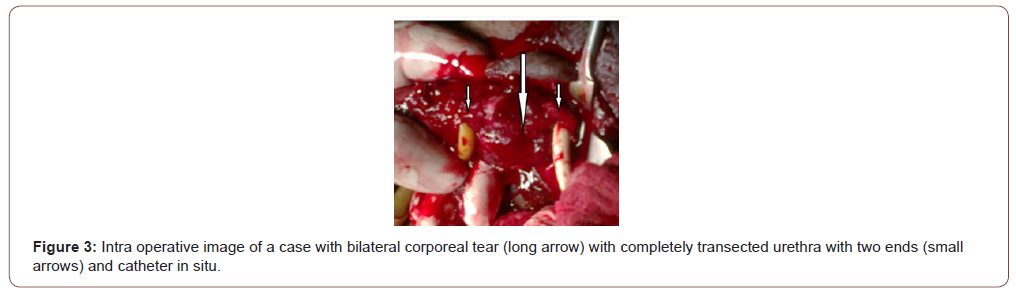

Most common site of injury was ventrolateral {32 (60.4%)} and location on shaft was proximal {49 (92.5%)}. One patient presented late (>72 hours) with Foley catheter per urethra and local abscess. On exploration he had bilateral corporal tear, and complete urethral transection with pus formation (Figure 3).

He was managed with SPC and corporeal repair followed by delayed urethral repair at 6 weeks. Later on he developed urethrocutaneous fistula which healed spontaneously. Mean follow up was 19.27 months, ranging from 6 to 41 months. Erectile function at six months was preserved (No deterioration in IIEF 5 category) in 96.3 % and 100% of patients from surgery and conservative groups (Table 3).

One of the two patients who had deterioration in erectile function was the aforementioned patient with delayed presentation and abscess. The other one also had bilateral corporeal tear. A two patients from surgery group had new onset ED (one mild and 1 mild to moderate ED). These patients had complete transection of urethra with bilateral corporeal tear.

Discussion

Penile fracture is not very rare. It is a clinical diagnosis, with some workers performing ultrasound or MRI in equivocal cases and for documentation. Shukla et al investigated role of ultrasound in cases of penile fracture. In their series of 15 patients they could localize the site of injury, hematoma and urethral injury. Moreover they proposed a classification system for same [5]. Such classifications need test of time. Metzler et al published an interesting editorial of use of penile ultrasound in patients suspected to have penile fracture to differentiate it from penile ecchymosis only. They had patients on collagenase clostridium histolyticum (CCH) injection for Peyronies disease. Such patients with penile ecchymosis were subjected to ultrasound and spared of surgery in absence of any tunical tear [6]. Another masquerader that needs to be differentiated is dorsal vein injury. Koifman and colleagues used ultrasound in 24.6% of suspected cases of penile fracture. They didn’t find any tunica tear in patients who underwent ultrasound after low suspicion of penile fracture impressing the importance of clinical diagnosis [7]. We at our institution don’t do ultrasound for patients with classical history suggestive of penile fracture. This avoids delay without any change in management. There is no doubt that ultrasound is a readily available, simple, cost effective, non-invasive method of evaluation; operator dependence and at times, severe oedema obscuring the tunical tear limits its potential. Magnetic resonance Imaging has also been explored in this clinical condition. It can accurately demonstrate the integrity of tunica albuginea and any defect if present which manifests as discontinuity of tunica. It is especially useful in cases where ultrasound is inconclusive [8]. It is more sensitive than ultrasound, better able to differentiate a rupture of circumflex or dorsal vein of penis or when penile fracture is not associated with tear in overlying Buck’s fascia [9]. A systematic review with total 438 patients was analysed. The most commonly reported cause of penile fracture was sexual intercourse (80% of cases) and most common finding at examination was penile hematoma (97.5% of cases). Concomitant urethral injury was reported in 15% of cases [10]. Our study in concordance, also had coital trauma as most frequent cause (88.9%) with penile ecchymosis and deviation, being the most common examination findings (80.9% each). The incidence of urethral injury (in surgery group) in our study was 9.4%. The recommended management of the condition is emergency surgical repair and evacuation of hematoma and urethral repair if present concomitantly. Under spinal anaesthesia, the surgical approach most commonly used is circumcoronal incision, penile degloving with inspection of whole corpora and spongiosa to avoid any missed injury [10]. But with advent of imaging which can pinpoint the defect, targeted incision could be planned to avoid complete degloving [11]. Non absorbable suture is avoided for repair as it remains palpable post operatively. Several studies have shown better results for surgical approach as compared to nonsurgical approach [12,13]. A recent meta-analysis including 58 studies and 3213 patients concluded that early surgical interventions led to decreased complications as compared to delayed surgery or conservative management. Specifically the erectile functions were better preserved in patients who underwent surgical intervention as compared to conservative management. Surgical intervention resulted in less erectile dysfunction, curvature and painful erection (p<0.000001). No significant difference was seen in number of patient developing plaques or nodules (p=0.94). Clinical diagnosis by history and physical examination and prompt surgical management is the key to reduce complications [14]. In a recent prospective comparative study Patil et al found delay in surgery (>/=24hrs) as a significant predictor for worse surgical and erectile functional outcomes [15]. They had total of 18 patients and quite high (44%) ED rates at 6 months in their series. Muentener et al in their series of 29 patients with 17 managed conservatively concluded that immediate surgery had superior results as compared to non-operative management, however conservative therapy limited to selected uncomplicated cases could lead to equally good outcome [16]. In a recent series of 32 patients author didn’t find any major complications in either conservative or surgical group. Total of 44% of patients in this study were managed conservatively. However, five patients from conservative group underwent surgery later on [17]. Erectile function was preserved (no change in pre and post op IIEF 5 category) in 96.3% and 100% of patients in surgical group and conservative group respectively at 6 months. Only 2 patients had decline in erectile function as compared to their pre-operative status, both were from surgery group with bilateral corporeal tear. The limitation of our study is its retrospective nature and limited number of patients in conservative group. The strengths are better assessment of erectile function objectively as well as its comparison with pre-operative status which is very important in such cases. Our study also highlights an unusual presentation and successful management of penile fracture with recurrent nocturnal urethral bleeding without any penile swelling, which is not mentioned in the literature. Larger cohort of patients may further give some more insights into results of conservative approach.

Conclusion

Penile fracture is a clinical diagnosis but ultrasound could be a handy instrument in case of dilemma. MRI can also be used but has constraints of availability and cost in emergency settings. Management should be surgical and in case of doubt, shared decision making with low threshold for exploration. Bucks fascia incision may be required to unveil tunical rent. Bilateral corporeal injury +/- urethral injury and delayed presentation are associated with poor erectile functional outcomes. Unexplained recurrent nocturnal urethral bleeding may be the only presenting feature of penile fracture and should be kept in mind. Careful history is of utmost importance. Such peculiar presentation, to our knowledge has not been reported in literature. This subgroup of patients can be managed conservatively with fair sexual and functional outcome.

Acknowledgment

None.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest.

References

- Morey AF, Zhao LC (2016) Genital and Lower Urinary Tract Trauma. In: Wein AJ, editor. Campbell-Walsh Urology, 11th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier p. 2379-2392.

- Al Ansari A, Talib RA, Shamsodini A, Hayati A, Canguven O, et al. (2013) Which is guilty in self-induced penile fractures: marital status, culture or geographic region? A case series and literature review. Int J Impot Res 25(6): 221-223.

- Zargooshi J (2002) Penile fracture in Kermanshah, Iran: the long-term results of surgical treatment. BJU Int 89(9): 890-894.

- Rosen R, Cappelleri J, Smith M, Lipsky J, Peña B (1999) Development and evaluation of an abridged, 5-item version of the International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF-5) as a diagnostic tool for erectile dysfunction. Int J Impot Res 11(6): 319-326.

- Shukla AK, Bhagavan BC, Sanjay SC, Krishnappa N, Sahadev R (2015) Role of Ultraosonography in Grading of Penile Fractures. J Clin Diagn Res 9: 1-3.

- Metzler IS, Reed-Maldonado AB, Lue TF (2017) Suspected penile fracture: to operate or not to operate. Transl Androl Urol 6(5): 981-986.

- Koifman L, Barros R, Júnior RAS, Cavalcanti AG, Favorito LA (2010) Penile fracture: diagnosis, treatment and outcomes of 150 patients. Urology 76(6): 1488-1492.

- Guler I, Ödev K, Kalkan H, Simsek C, Keskin S, et al. (2015) The value of magnetic resonance imaging in the diagnosis of penile fracture. Int Braz J Urol 41: 325-328.

- Antonini G, Vicini P, Sansalone S, Garaffa G, Vitarelli A, et al. (2014) Penile fracture: penoscrotal approach with degloving of penis after Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI). Arch Ital Urol Androl 86(1): 39-40.

- Falcone M, Garaffa G, Castiglione F, Ralph DJ (2018) Current Management of Penile Fracture: An Up-to-Date Systematic Review. Sex Med Rev 6(2): 253-260.

- De Luca F, Garaffa G, Falcone M, Raheem A, Zacharakis E, et al. (2017) Functional outcomes following immediate repair of penile fracture: a tertiary referral centre experience with 76 consecutive patients. Scand J Urol 51(2): 170-175.

- Gamal WM, Osman MM, Hammady A, Aldahshoury MZ, Hussein MM, et al. (2011) Penile Fracture: Long-Term Results of Surgical and Conservative Management. J Trauma Inj Infect Crit Care 71(2): 491-493.

- Yamaçake KGR, Tavares A, Padovani GP, Guglielmetti GB, Cury J, et al. (2013) Long-term Treatment Outcomes Between Surgical Correction and Conservative Management for Penile Fracture. Retrospective Analysis Korean J Urol 54: 472-476.

- Amer T, Wilson R, Chlosta P, Al Buheissi S, Qazi H, et al. (2016) Penile Fracture: A Meta-Analysis. Urol Int 96(3): 315-329.

- Patil B, Kamath SU, Patwardhan SK, Savalia A (2019) Importance of time in management of fracture penis: A prospective study. Urol Ann 11: 405-409.

- Muentener M, Suter S, Hauri D, Sulser T (2004) Long-Term Experience With Surgical and Conservative Treatment of Penile Fracture. J Urol 172(2): 576-579.

- Ouellette L, Hamati M, Hawkins D, Bush C, Emery M, et al. (2019) Penile fracture: Surgical vs conservative treatment. Am J Emerg Med 37: 366-367.

-

Mukesh Chandra Arya, Vivek Vasudev, Yogendra shyoran, Abhiyutthan Singh Jadon, Ajay gandhi, Ankur Singhal. Unexplained Recurrent Nocturnal Urethral Bleeding: An Unusual Presentation of Penile Fracture. Annal Urol & Nephrol. 2(2): 2020. AUN.MS.ID.000533.

-

Nocturnal urethral bleed, Penile fracture, Conservative management, erectile dysfunction, Emergency urological condition, Retrospective analytical study, Haematology, Biochemistry investigations

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.