Research Article

Research Article

Understanding the Time-Course of Nephrolithiasis Management

Seth K Bechis*, Daniel G Kronenberg, Rachel M Shapiro, David F Friedlander and Roger L Sur

Department of Urology, UC San Diego Health, USA

Seth K Bechis, Department of Urology, UC San Diego Health, 200 West Arbor Drive, Mail Code 8897, San Diego, CA 92013, USA.

Received Date: February 27, 2020; Published Date: March 19, 2020

Abstract

Purpose: The growing incidence of acute nephrolithiasis has increased the burden on healthcare. We sought to assess the time-course of acute stone disease treatment from symptom onset to spontaneous passage or definitive treatment to better characterize the current state of management and identify areas for improvement. Methods: We performed a retrospective review of patients treated for acute nephrolithiasis from August 2016 until February 2017. Patients were included if they had symptomatic renal or ureteral stones, evaluation by urology, and documented resolution by spontaneous passage or surgery. Primary outcome was the time from initial presentation at the Emergency Department (ED) to procedure or passage. Secondary outcomes included time to outpatient evaluation by urology and delays to procedure scheduling greater than 14 days. Results: 61 patients (41% female) met selection criteria. Median time from initial presentation to procedure or stone passage was 45 or 26 days, respectively. Median time from ED to clinic visit was 12.5 days. Time from clinic visit to procedure or spontaneous passage was 29 or 16 days, respectively. 38 patients (62%) had documented causes for delay in treatment. Of this cohort, 22 (58%) were due to provider availability issues, 8 (21%) had contraindications to surgery, and 8 (21%) had patient-related delays.

Conclusion: Prolonged time to treatment of acute nephrolithiasis occurred in 30 (49%) of the cohort due to provider availability and patientspecific delays. Developing initiatives to expedite management through improved patient education and operating room availability may help reduce healthcare costs and patient discomfort.

Keywords: Kidney stones; Time-course; Urolithiasis; Ureteroscopy; SWL; PCNL

Abbreviations: ACU: acute care urology, AUA: American Urological Association, ED: Emergency Department, EHR: Electronic health record, IRB: Institutional Review Board, MET: Medical expulsive therapy, NHANES: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, UC: Urgent Care

Introduction

The incidence of kidney stones has been noted to be 8.4% in the United States as of 2010, a dramatic increase from 5.2% in 1994 based on analysis of NHANES data [1]. The rising incidence, morbidity and cost of kidney stone disease place a major burden on the U.S. healthcare system [2,3]. Reducing healthcare costs and ultimately improving quality of care first requires an evaluation of the current status of urolithiasis treatment as well as identification of obstacles to care. Current data show an average 3.4 urologists per 100,000 persons in the U.S., with a substantial shift toward metropolitan regions and an estimated 38 million Americans living in counties without a single urologist [4]. This lack of availability of timely urologic care leads to costly repeat emergency department visits [5,6]. Our study aimed to assess, at a single tertiary care center, the time-course of nephrolithiasis treatment, from onset of symptoms and initial presentation to resolution either by definitive treatment or spontaneous passage. We hypothesized that time to treatment or passage was greater than 30 days.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective review of patients treated for nephrolithiasis at a single, tertiary academic center from August 2016 to February 2017. Under an IRB-approved protocol (#170854), medical records were reviewed for patients at least 18 years of age seen at the UC San Diego Health Comprehensive Kidney Stone Center. Inclusion criteria were history of symptomatic renal or ureteral stones (i.e., causing colic), presentation at a San Diego Emergency Department (ED), Urgent Care (UC) or other clinic, subsequent evaluation at our urology clinic, and documented resolution of their stone(s) by either spontaneous passage or surgical procedure. Spontaneous passage was confirmed via a submitted sample of a passed stone or subsequent imaging results. The primary outcome of the study was the time from initial presentation at the ED, UC or clinic to surgical procedure or spontaneous passage. Secondary outcomes included time from first ED or UC presentation to evaluation by urology, time from initial presentation to spontaneous stone passage, and delays in procedure scheduling greater than 14 days following first urology clinic appointment (designated as “delay in treatment time”). Fourteen days was set by institution as a goal to achieve in order to optimize patient care. Patients with delays in treatment time were included in sub-group analyses only if reasons for delay were documented within the electronic health record. In order to capture the entire time-course of a stone episode, patients were excluded from the study if by the end of the review period they had not yet had surgery to remove their stone(s), had not yet passed their stone(s) spontaneously, or were unsure of stone passage. Descriptive statistical analyses were performed.

Results

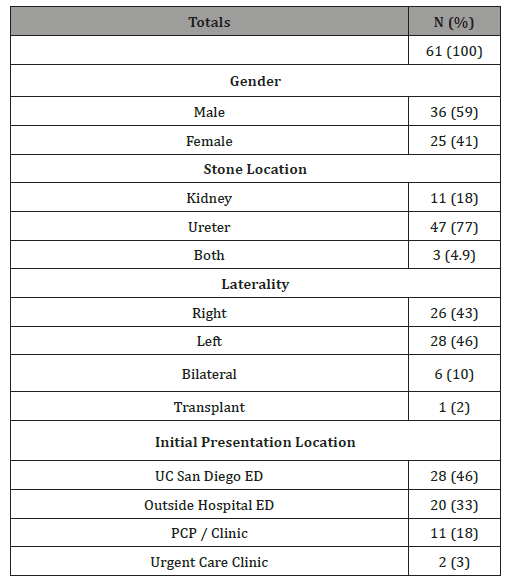

During the study period, 61 patients met inclusion criteria (see Table 1).

Table 1: Demographic data for time course study subjects.

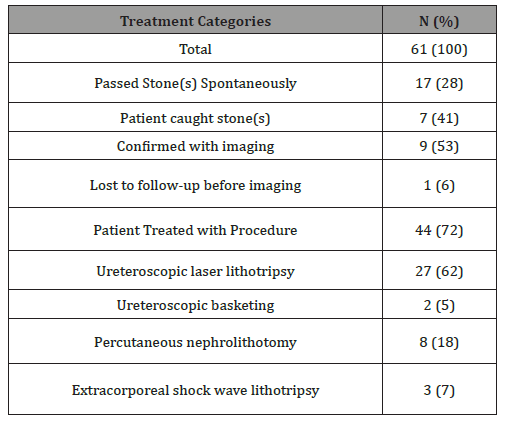

A majority of the study cohort (44 patients, 72%) was treated with surgery, with ureteroscopy being the most common procedure (72%); 17 patients (28%) passed their stones spontaneously with MET or supportive care alone(Table 2).

Table 2: Stone treatment outcomes/procedures for time course study subjects.

Emonstrates the specific data for stone passage or treatment method as documented in the EHR. Overall, the median time from initial presentation at the ED/UC/Clinic to stone resolution via procedure or spontaneous passage was 41 days (see Figure 1).

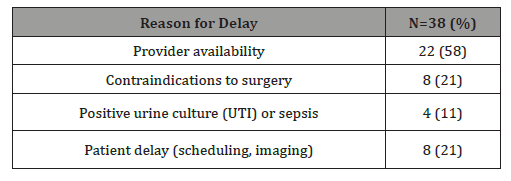

Table 3: Reasons for delays to treatment.

Median time from initial presentation to surgery or spontaneous passage was 45 or 27 days, respectively. The median time between initial presentation and first Urology clinic visit was 12.5 days. In total, the median time from the first appointment with Urology until resolution via a procedure or spontaneous stone passage was 29 days or 16 days, respectively, with 28 days overall. Of the total cohort, 38 study subjects (62%) waited greater than 14 days between the first Urology appointment and surgery (Table 3).

Analyzing this subgroup, the majority (22 patients, 58%) of the delays were due to provider availability issues (including operating room, staff, and/or surgeon availability). Another 8 patients (21%) were delayed due to contraindications to surgery. These included a positive pre-operative urine culture (2 patients); urosepsis (2); recent abdominal aortic aneurysm surgery and on anticoagulation (1); admission for small bowel obstruction (1); epididymo-orchitis (1); and ureteral perforation during initial urgent ureteral stent placement (1). Definitive treatment for 8 patients was delayed due to patient-related issues including missed clinic or imaging appointments or lack of call back to schedule their surgery.

Discussion

Our study aimed to assess, at a single U.S. tertiary care center, the time-course of nephrolithiasis treatment, from onset of symptoms and initial presentation to definitive treatment and follow-up imaging. We found that patients waited an average of 45 days until surgical treatment of their stones. This timeframe is clinically concerning given the risks of ED revisits for renal colic and/or infection as well as long-term risks of chronic kidney disease and ureteral stricture after 6 weeks [6-8]. The American Urological Association (AUA) guidelines for surgical management of urolithiasis provides a moderate recommendation for definitive stone management within 6 weeks, based on a 1973 study noting irreversible upper tract damage after this time frame [9]. Our data is in line with other studies in the literature. One U.S. group found that the median time from ED visit and/or stent placement to definitive stone intervention was 31.5 days [10]. In Canada, the mean wait time in 2011 for elective ESWL procedures nationally was 59 days [11]. A retrospective review of a 6 month period in the United Kingdom found a median time from ED visit and stent placement to stone intervention of 119 days, with only 3% receiving definitive procedure within 30 days [12]. This contrasts sharply with the British Association of Urologic Surgeons (BAUS) proposed target time of 4 weeks for definitive intervention in patients with acute stone presentations [12]. The most common reason 62% of patients waited more than 14 days for surgery was due to lack of provider availability or inability to access sooner operating room time. At our institution, surgical scheduling is based on a rigid block schedule that discourages non-urgent add-on cases. For example, each surgeon performs urological surgery on scheduled days of the month and open time for elective cases in between these blocks rarely exists. This makes scheduling patients with semi-acute but non-urgent stones challenging. Other healthcare systems with more flexibility may have improved access to surgical treatment. A recent population- based cohort study by Brubaker et al of over 15,000 patients discharged from an ED in California with a stone diagnosis found a median time from ED to stone surgery of 28 days [13]. Interestingly, patients with Medicare, Medicaid or self-pay coverage as well as Black or Hispanic race experienced a wait of up to 12 to 36 days longer, bringing the time to definitive treatment to 6 to 9 weeks. Our study complements this large dataset as we verify findings at a single institution similar to Brubaker et al. In addition, our study provides clinical granularity about reasons for delay that is lacking in administrative datasets. Implementation of protocols to enhance follow-up and expedite treatment of acute stone episodes is in its infancy but already shows significant promise to improve healthcare- associated costs as well as patient morbidity [10, 14]. The formation of an acute care urology (ACU) service at one New York hospital to facilitate timely evaluation and treatment of patients presenting to the ED with acute stone disease was found to reduce ED return visits and hospital readmissions [10]. At our own institution, measured institution goals for access to care exist, and enhancing access to surgery is an ongoing goal. Our study is not without limitations. It is retrospective in nature and focused on a small cohort at a tertiary referral center. In addition, we did not capture data about payer status, race or medical comorbidities. Therefore, it is possible that the surgical stone cases at our institution may be more complex and require more specialized care than cases found in the community. In addition, as mentioned previously, our current surgical scheduling model does not easily accommodate expedited surgical cases. However, the predominance of ureteral stones and gender equality amongst our patients with acute renal colic is in line with that of the greater population. Future research will be focused on prospectively following patients to further identify obstacles in accessing care.

Conclusion

In our study of the time-course of acute nephrolithiasis, we found that the time from initial presentation to stone treatment was prolonged primarily due to provider availability, challenges in accessing expedited operating room time, and patient factors. These data suggest that improving provider availability, perhaps by incorporating a dedicated operating room to enable faster access for stone surgery cases, is critical to improving the overall morbidity and outcomes of acute stone management.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. This study was IRB approved. For this type of retrospective study, formal consent is not required.

Disclosure of Interest Statement

The authors have no interests to disclose.

Acknowledgement

None.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest.

References

- Scales CD Jr, Smith AC, Hanley JM, Saigal CS (2012) Prevalence of kidney stones in the United States. European Urology 62(1): 160-165.

- Saigal CS, Joyce G, Timilsina AR (2005) Direct and indirect costs of nephrolithiasis in an employed population: opportunity for disease management? Kidney International 68(4): 1808-1814.

- De SK, Liu X, Monga M (2014) Changing trends in the American diet and the rising prevalence of kidney stones. Urology 84(5): 1030-1033.

- Odisho AY, Fradet V, Cooperberg MR, Ahmad AE, Carroll PR (2009) Geographic distribution of urologists throughout the United States using a county level approach. J Urol 181(2): 760-765.

- Colli JL, Amling CL (2008) Prostate cancer mortality rates compared to urologist population densities and prostate-specific antigen screening levels on a state-by-state basis in the United States of America. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis 11(3): 247-251.

- Scales CD Jr, Lin L, Saigal CS, Bennett CJ, Ponce NA, et al. (2015) Emergency department revisits for patients with kidney stones in California. Acad Emerg Med 22(4): 468-474.

- Vaughan ED Jr, Gillenwater JY (1971) Recovery following complete chronic unilateral ureteral occlusion: functional, radiographic and pathologic alterations. J Urol 106(1): 27-35.

- Hubner WA, Irby P, Stoller ML (1993) Natural history and current concepts for the treatment of small ureteral calculi. European Urology 24(2): 172-176.

- Assimos D, Krambeck A, Miller N L, Monga M, Murad MH, et al. (2016) Surgical Management of Stones: American Urological Association/Endourological Society Guideline, PART I. J Urol 196(4): 1161-1169.

- Mikkilineni N, Weiner D, Li G, Shah O, Healy KA (2019) Impact of Acute Care Urology Service on Care of the Acute Stone Patient. Journal of Urology 201(4): E847-E847.

- Piggott KL, Bell CM (2013) Looking for lithotripsy: accessibility and portability of Canadian healthcare. Healthc Policy 9(2): 65-75.

- Balai EBC, Pal P, Graham S, Siddique U (2018) MP31-10: A closed loop audit of all emergency ureteric stent insertion within a large district-general hospital: Are patients waiting too long for further procedures and what is the morbidity related to stent-symptoms? World Congress of Endourology, Paris.

- Brubaker WD, Dallas KB, Elliott CS, Pao AC, Chertow GM, et al. (2019) Payer Type, Race/Ethnicity, and the Timing of Surgical Management of Urinary Stone Disease. J Endourol 33(2): 152-158.

- Moghul MWJ, Goyal A, Kucheria R, Allen D, Ajayi L (2018) MP28-18: Delays in Emergency Urological Stent Insertions – Case for an Emergency Pathway for Obstructing Stones. World Congress of Endourology, Paris.

-

Seth K Bechis, Daniel G Kronenberg, Rachel M Shapiro, David F Friedlander, Roger L Sur. Understanding the Time-Course of Nephrolithiasis Management. Annal Urol & Nephrol. 1(5): 2020. AUN.MS.ID.000525.

-

Kidney stones, Time-course, Urolithiasis, Ureteroscopy, SWL, PCNL, Acute nephrolithiasis, Symptomatic renal, Ureteral stones, Urology appointment, Surgery, Delay in treatment time, California, Stone diagnosis

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.