Review Article

Review Article

Surgical Options for Post-Prostatectomy Incontinence: A Review

Alixandra Ryan1* and Colin Goudelocke2

1University of Queensland-Ochsner Clinical School, New Orleans, LA, USA

2Department of Urology, Ochsner Health, New Orleans, LA, USA

Alixandra Ryan, University of Queensland-Ochsner Clinical School Ochsner Health, New Orleans, LA, USA.

Received Date: October 20, 2020; Published Date: November 12, 2020

Abstract

Introduction: Post-prostatectomy incontinence affects anywhere from 1-40% of men after a radical prostatectomy, but treatment is often delayed and surgery is underperformed.1 Currently, the American Urological Association (AUA) and Society of Urodynamics, Female Pelvic Medicine and Urogenital Reconstruction (SUFU) recommends post-prostatectomy patients are offered conservative therapies including pelvic floor muscle training in the immediate post-operative period, and surgical treatment may be offered to those who have confirmed stress incontinence (SUI) and fail to respond to conservative therapies. Surgical treatment options are based on the degree of stress urinary incontinence. The artificial urinary sphincter is typically recommended for moderate to severe SUI, while the male sling can be considered in those with mild to moderate SUI.2 However, the AUS is considered a more reliable treatment, particularly for severe SUI after prostatectomy.

Methods: The study was conducted using the PubMed database for recent papers between 2001 and 2020 with variations of phrases such as post-prostatectomy incontinence, treatment, AUS, male sling [1]. articles were selected for review. The AUA/SUFU guidelines for incontinence after prostate treatment were also referenced.

Results: The AUS is considered the gold standard of post-prostatectomy incontinence therapy. However, male slings are gaining popularity in the treatment of mild to moderate PPI. The overall consensus is a need for prospective research based upon standardized patient workup and outcomes reporting to better compare the surgical options for PPI.

Conclusion: Standardized workup and outcomes reporting would benefit the patient in determining which surgical option best treats postprostatectomy incontinence. As of right now, there is no standardized approach apart from history and physical exam of the patient. Cystoscopy and urodynamics could be a beneficial tool in evaluation patients pre- and post-operatively. Prospective randomized control trials could then utilize a standardized approach to better compare the surgical options for PPI.

Keywords: Post-prostatectomy incontinence, AUS, Male sling

Abbreviations: AUA: American urological association; SUFU: Society of urodynamics, female pelvic medicine and urogenital reconstruction; PPI: Post-prostatectomy incontinence; AUS: Artificial urethral sphincter; SUI: Stress urinary incontinence; ppd: Pads per day; RCT: Randomized control trial

Introduction

Post-prostatectomy incontinence affects anywhere from 1-40% of men after a radical prostatectomy, but treatment is often delayed, and surgery is underperformed [2]. It is estimated 10-20% of men experience severe SUI compared to the 6% who actually undergo a PPI surgery [3]. Current the AUA/SUFU guidelines recommend those who have bothersome SUI unresponsive to conservative therapies may be offered surgical therapy as early as 6 months if incontinence is not improving and should be offered this therapy by 12 months if not satisfied [4]. However, the mean time to surgery for SUI from radical prostatectomy is 2.8 years [3]. Patients undergoing prostatectomy should be informed that incontinence is typical in the short-term resolving by 12 months post-operatively in most cases but may persist in some men without further therapy [4]. Patients are recommended pelvic floor muscle exercises during the post-operative time period. Currently, the AUA/SUFU recommends evaluation with history, physical exam, and appropriate diagnostic modalities to determine the type and degree of incontinence [4]. The aim of this evaluation is to categorize the type of incontinence, determine the severity and bother of incontinence, and determine any complicating factors such as radiation therapy or persistent prostate cancer. Incontinence may be determined to be urgency, stress or mixed incontinence. Urgency incontinence is treated based on overactive bladder guidelines and will not be discussed here. Stress incontinence should be confirmed before surgical treatment options are offered. Stress incontinence may be confirmed using a combination of history and visual confirmation on physical exam, though some patients may require ancillary testing such as urodynamic evaluation (UDS) if additional storage or voiding dysfunction is suspected. The overarching opinion is that cystourethroscopy is to be performed as part of this confirmation to rule out bladder or urethral pathology [4]. Surgical treatment options are based on degree of stress urinary incontinence. An artificial urinary sphincter is typically recommended for moderate to severe SUI, while the male sling can be considered in those with mild to moderate SUI [2]. The AUS is considered a more predictable therapy than the male sling, but the requirements of a mechanical device must also be taken into consideration and discussed with patients.

Discussion

Methods

The study was conducted using the PubMed database for recent papers between 2001 and 2020 with variations of phrases including “post-prostatectomy incontinence”, “treatment”, “AUS”, “male sling”. The search yielded 108 results of which were filtered through based on title and/or abstract. Results not pertaining to patients who had undergone radical prostatectomy were filtered out. Other excluded results were studies focusing on cost-effectiveness, surgical technique, and poor-quality studies [5]. articles were selected for review. The AUA/SUFA guidelines were also referenced.

Result

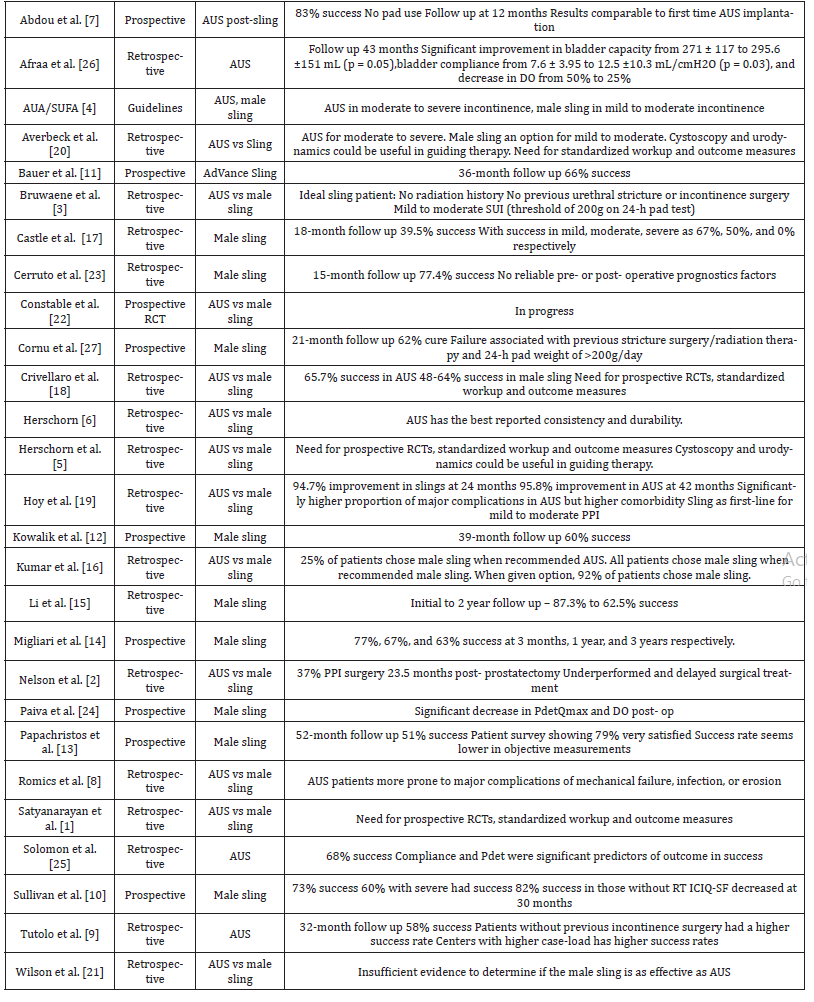

Key points of articles were summarized in (Table 1).

Table 1:Article Summaries.

Discussion

Artificial urinary sphincter (AUS)

The AUS is considered the gold standard due to the extensive amount of published information on its use for the treatment of moderate to severe PPI [6]. Published reports on AUS data dating back to the 1990s consisted of the largest number of patients compared to other treatments. Not only is there extensive data on the device but the data have been consistent. According to Herschorn, the success of the AUS is between 59- 90%. The definition of success in this report was the use of 0-1 pads per day. However, the definition of continence does depend on the method of evaluation and success varies when using patient-administered questionnaires and pad-free rates. Despite the variation in continence, the patient satisfaction rate is high at 87-90% [6]. Considerations for an AUS placement include the patient’s ability to operate the device and the need for future reoperation due to loss of effectiveness over time. Patients with the AUS are more likely to have complications leading to revision [7,8]. The revision rate for the AUS due to mechanical failure, urethral atrophy, infection, or erosion varies, but Hershorn reports a 23% revision rate.4 A study by Tutolo et al. found a higher success rate in patients without previous incontinence surgery [9]. Previous pelvic radiation is not a contraindication for the AUS as with the male sling.4 However, based on a study by Walsh et al., the revision rate was reported as 41% in irradiated patients compared to 11% in those without irradiation [3] Despite the risk of needing a revision, the longterm durability is still considered superior. In addition, an AUS implantation after sling failure has comparable outcomes to first line AUS placement in mild to moderate incontinence patients [7].

Male sling

Although the AUS is considered the gold standard, the male sling has become a popular option for patients due to ease of surgery, improved outcomes, and low complications. A 21-month prospective, follow- up study found a cure rate of 62% defined by no pad usage.8 In this study, failure was associated with previous urethral stricture, incontinence surgery, or radiation therapy and pre-op 24-h pad weight of more than 200g/day. Another 34-month prospective follow-up study reported 73% of patients had complete resolution of symptoms and 60% of severe incontinence patients had resolution [10]. Additional prospective studies found a 66% success rate at 36-months and a 60% success rate at 39-months [11,12]. In a 52-month follow up, 51% of patients were reportedly using 0-1 ppd and 25% reported a 50 percent reduction in pad use [13]. Another prospective study found a success rate of 77%, 67%, and 63% at 3-month, 1-year, and 3-years respectively [14]. A retrospective study reported a decline in the success rate from 87.3% at initial follow-up to 62.5% at 2-years [15]. The most appealing factor of the male sling to patients compared to the AUS appears to be the absence of having to operate the device. In fact, one study found when given the choice, 92% of patients chose the male sling [16]. As many as 25% of patients are willing to go against surgeon recommendations of the AUS in favor of the male sling. However, the male sling fails to show similar robust results in patients who have a history of pelvic radiation history with only a 54% success rate [3]. The male sling also shows inferior outcomes in patients with a history of urethral stricture or bladder neck contracture. All the above-mentioned factors continue to be relative contraindications to use of a male sling. Based on numerous studies, the ideal candidate for a male sling has no history of radiation, previous stricture or contracture, as well as having only mild to moderate incontinence with a maximum of 200g on a 24-hour pad test and good urethral mobility [17,18].

AUS vs Sling

Success is usually defined by the use of 0-1 pad per day, although some studies define success as 50% improvement in pad use [18]. One study reported the AUS has an average success rate of 83% compared to the 71-75% success rate of male slings [3]. Another review found the average success rate was 65.7% for the AUS and between 48-64% for the male sling [18]. This study concluded that the success in AUS studies was better defined and likely gave the data on the AUS more of an advantage. Looking at mild to moderate incontinence, specifically, one retrospective study found no significant difference in continence rates, improvement rate, or patient satisfaction; however, the follow-up was at 42 months for the AUS and 24 months for the male sling [19]. The only significant difference found was the rate of more severe complications tended to be higher in the AUS population but that was likely due to the higher rates of co-morbidity scores and previous radiation. The AUS continues to be considered the preferred treatment for moderate to severe incontinence; however, there are fewer studies available on the newer male sling [20, 21]. A RCT study by Constable et al. is currently in progress to compare the AUS and male sling [22]. The study aims to use patient questionnaires, 3- day bladder diaries, and 24-h pad test to determine outcomes. Prospective, randomizedcontrol trials would greatly benefit the future of surgical options for post-prostatectomy incontinence.

Factors influencing patient selection and outcomes

The decision between the AUS or the male sling depends on a number of factors. Unfortunately, when stratifying patients preoperatively and measuring outcomes, a standard algorithm is lacking. The currently available studies fail to incorporate reliable pre- and post-operative prognostic factors [23]. Having a standard algorithm will help better select patients for the appropriate procedure. One report looked at urodynamic factors pre- and postoperatively for male sling surgery. Significant findings included changes in detrusor pressure at maximum flow and presence of detrusor overactivity compared to preoperative studies [24]. Another study found compliance and detrusor pressure were good predictors of outcome in patients with the AUS [25]. An additional study found bladder capacity, compliance, and presence of DO were a few urodynamic variables showing improvement post-AUS implantation [26]. Urodynamics could have a promising role in the standard evaluation; however, they currently are recommended to a lesser degree due to insufficient supporting evidence.

Conclusion

The overall consensus is that an algorithm for selecting patients for the AUS or the male sling would benefit from prospective research [1,5,20,27]. Standardizing the workup and outcome measurements would greatly improve patient selection and evaluating outcomes. Some studies have already begun to look at urodynamic data and QOL questionnaires for determining the success of postprostatectomy incontinence procedures. However, due to the lack of standardization, retrospective studies fail to identify pre- and postoperative factors. Urodynamics could offer great objective data in the workup of a patient for post- prostatectomy incontinence. Although more subjective, a standard QOL questionnaire could help quantify patient satisfaction rates. Prospective data is necessary to better compare the outcomes between surgical options for postprostatectomy incontinence.

Acknowledgement

None.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest.

References

- Satyanarayan A, Mooney R, Singla N (2016) Surgical Management of Post-Prostatectomy Incontinence. Eur Med J Urol 4(1): 75-80.

- Nelson M, Dornbier R, Kirshenbaum E, Emanuel E, Sweigert P, et al. (2020) Use of Surgery for Post-Prostatectomy Incontinence. Journal of Urology 203(4): 786-791.

- Van Bruwaene S, De Ridder D, Van der Aa F (2015) The use of sling vs sphincter in post-prostatectomy urinary incontinence. BJU International 116(3): 330-342.

- Sandhu JS, Breyer B, Comiter C, Eastham JA, Gomez C, et al. (2019) Incontinence after Prostate Treatment AUA/SUFA. Urol J 202(2): 369-378.

- Herschorn S, Bruschini H, Comiter C, Grise P, Hanus T, et al. (2010) Surgical treatment of stress incontinence in men. Neurourol Urodyn 29(1): 179-190.

- Herschorn S (1969) The artificial urinary sphincter is the treatment of choice for post–radical prostatectomy incontinence. Canadian Urological Association Journal 2(5): 536-539.

- Abdou A, Cornu JN, Sèbe P, Ciofu C, Peyrat L, et al. (2012) Salvage therapy with artificial urinary sphincter after Advance™ male sling failure for post-prostatectomy incontinence: a first clinical experience. Prog Urol 22(11): 650-656.

- Romics M, Bánfi G, Keszthelyi A, Klingler CH, Szarvas T, et al. (2020) Major Complications after Male Anti-IncontinenceProcedures: Predisposing Factors. Management and Prevention. Urol J.

- Tutolo M, Cornu JN, Bauer RM, Ahyai S, Bozzini G, et al. (2019) Efficacy and safety of artificial urinary sphincter (AUS): Results of a large multi-institutional cohort of patients with mid-term follow-up. Neurourol Urodyn 38(2): 710-718.

- Sullivan JF, Stassen PN, Moran D, Bolton EM, Smyth GL, et al. (2018) The transobturator suburethral sling: a safe and effective option for all degrees of post prostatectomy urinary incontinence. Can J Urol 25(2): 9268-9272.

- Bauer RM, Grabbert MT, Klehr B, Gebhartl P, Gozzi C, et al. (2017) 36-month data for the AdVance XP (®) male sling: results of a prospective multicentre study. BJU Int 119(4): 626-630.

- Kowalik CG, DeLong JM, Mourtzinos AP (2015) The advance transobturator male sling for post-prostatectomy incontinence: Subjective and objective outcomes with 3 years follow up. Neurourology and Urodynamics 34(3): 251-254.

- Papachristos A, Mann S, Talbot K, Moon D (2018) AdVance male urethral sling: medium-term results in an Australian cohort. ANZ J Surg 88(3): E178-E182.

- Migliari R, Pistolesi D, Leone P, Viola D, Trovarelli S (2006) Male bulbourethral sling after radical prostatectomy: intermediate outcomes at 2 to 4-year followup. J Urol 176(5): 2114-2118.

- Li H, Gill BC, Nowacki AS, Montague DK, Angermeier KW, et al. (2012) Therapeutic durability of the male transobturator sling: midterm patient reported outcomes. J Urol 187(4): 1331- 1335.

- Kumar A, Litt ER, Ballert KN, Nitti VW (2009) Artificial Urinary Sphincter Versus Male Sling for Post-Prostatectomy Incontinence -What Do Patients Choose. Journal of Urology 181(3): 1231-1235.

- Castle EP, Andrews PE, Itano N, Novicki DE, Swanson SK, et al. (2005) The male sling for post-prostatectomy incontinence: mean followup of 18 months. J Urol 173(5): 1657-1660.

- Crivellaro S, Morlacco A, Bodo G, Agro FE, Gozzi C, et al. (2016) Systematic review of surgical treatment of post radical prostatectomy stress urinary incontinence. Neurourology and Urodynamics 35(8): 875-881.

- Hoy NY, Rourke KF (2014) Stemming the tide of mild to moderate post-prostatectomy incontinence: A retrospective comparison of transobturator male slings and the artificial urinary sphincter. Canadian Urological Association Journal 8(7-8): 273-277.

- Averbeck MA, Woodhouse C, Comiter C, Bruschini H, Hanus T, et al. (2019) Surgical treatment of post-prostatectomy stress urinary incontinence in adult men: Report from the 6th International Consultation on Incontinence. Neurourol Urodyn 38(1): 398-406.

- Wilson LC, Gilling PJ (2011) Post-prostatectomy urinary incontinence: a review of surgical treatment options. BJU Int 107 Suppl 3: 7-10.

- Constable L, Cotterill N, Cooper D, Glazener C, Drake JM, et al. (2018) Male synthetic sling versus artificial urinary sphincter trial for men with urodynamic stress incontinence after prostate surgery (MASTER): study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials 19(1): 131.

- Cerruto MA, D'Elia C, Artibani W (2013) Continence and complications rates after male slings as primary surgery for post-prostatectomy incontinence: a systematic review. Arch Ital Urol Androl 85(2): 92-95.

- Paiva OG, Lima JPC, Bezerra CA (2018) Evaluation of urodynamic parameters after sling surgery in men with post- prostatectomy urinary incontinence. Int Braz J Urol 44(3): 536-542.

- Solomon E, Veeratterapillay R, Malde S, Harding C, Greenwell TJ (2017) Can filling phase urodynamic parameters predict the success of the bulbar artificial urinary sphincter in treating post-prostatectomy incontinence. Neurourol Urodyn 36(6): 1557-1563.

- Afraa TA, Campeau L, Mahfouz W, Corcos J (2011) Urodynamic parameters evolution after artificial urinary sphincter implantation for post-radical prostatectomy incontinence with concomitant bladder dysfunction. Can J Urol 18(3): 5695-5698.

- Cornu JN, Sèbe P, Ciofu C, Peyrat L, Cussenot O, et al. (2011) Mid-term evaluation of the transobturator male sling for post-prostatectomy incontinence: focus on prognostic factors. BJU Int 108(2): 236-240.

-

Alixandra Ryan, Colin Goudelocke. Surgical Options for Post-Prostatectomy Incontinence: A Review. Annal Urol & Nephrol. 2(2): 2020. AUN.MS.ID.000534.

-

Post-prostatectomy incontinence, AUS, Male sling, Cystoscopy, Urodynamics, Urodynamic evaluation, Artificial urinary sphincter

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.