Review Article

Review Article

Evaluation of Laser Therapy for Urgency Urinary Incontinence in Females

Ali Abid* and Emmanuel Karantanis

The University of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia

Ali Abid, The University of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia.

Received Date: February 26, 2021; Published Date: April 06, 2021

Abstract

Urgency urinary incontinence is a major health problem associated with detriments to the social, mental and economical spheres of an affected individual’s life. It is a symptom that is implicated in many syndromes such as overactive bladder, genitourinary syndrome of menopause and mixed urinary incontinence. The exact cause of urgency urinary incontinence has not been elucidated however some theories point to detrusor overactivity, poor bladder compliance and urothelial hypersensitivity as the culprits. The management of urgency urinary incontinence includes a stepwise approach beginning with behavioural and lifestyle modifications and physical therapy followed by pharmacological agents and then, for severe cases, surgical management. Laser therapy is a novel, non-hormonal, minimally invasive treatment approach that is rising in prominence in the literature. In this review an evaluation of the literature is conducted, appraising any relevant studies to determine if laser therapy is a viable management approach. Our finding is that at this current juncture there is not enough evidence to support the implementation of laser therapy for urgency urinary incontinence.

Keywords: Female urinary incontinence; Laser; CO2; Er: YAG; Urge; Overactive bladder; Genitourinary syndrome of menopause; Mixed urinary incontinence

Introduction

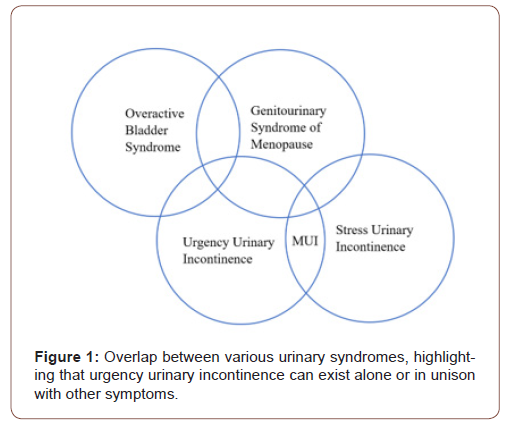

Urinary incontinence

Urinary incontinence is defined as the involuntary leakage of urine [1] Continence is maintained via the coordinated interplay of the bladder, urethra, pelvic floor musculature, ligaments and fascia of the pelvis as well as being influenced by neurological modulation, all of which can be compromised through various mechanisms [2] Risk factors for female urinary incontinence include advanced age, pregnancy, prolonged labour, vaginal childbirth, menopause, obesity, chronic cough and constipation [3]. Urinary incontinence is major health problem affecting 12.8-46% of women in Australia [4], causing significant morbidity and reduction in quality of life. Furthermore, it is associated with an enormous economic burden on the individual and the health system. The wide variation in the aforementioned prevalence estimate may exist because urinary incontinence is a condition which is under-reported, possibly due to misconceptions of it being a disease or stigma associated with the symptoms, precluding patient presentation [3]. Although its prevalence increases with age, it is not a phenomenon related to the normal aging process like presbyopia or presbycusis is [5]. Thus, with the current demographic trends of an aging Australian population, urinary incontinence is likely to place a greater load on the health system. According to the joint report by the International Urogynecology Association and the International Continence Society on female pelvic floor dysfunction, there are two main types of urinary incontinence: stress urinary incontinence (SUI) and urgency incontinence [1] SUI occurs when there are increases in intraabdominal pressure such as during coughing, sneezing, laughing, or lifting heavy objects, which results in the loss of a small amount of urine. Urgency incontinence is the passage of urine in combination with a strong and compelling desire to void (urgency), which is difficult to defer. Many women who have urgency incontinence are also diagnosed with a syndrome called overactive bladder (OAB) which includes the symptoms of urgency (with or without incontinence), frequency and nocturia, in the absence of infection or other pathology [3]. Women who complain of symptoms of incontinence associated with both urgency and physical exertion are said to have mixed urinary incontinence. Those women who have reached the menopause often experience symptoms related to the decrease in oestrogen levels. These symptoms include vasomotor effects as well as the genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM). GSM includes vaginal dryness, irritation, burning as well as stress and urgency incontinence [6]. Thus, urgency incontinence can exist on its own or be a component of other syndromes. Figure 1 demonstrates the overlap that can exist with different urinary syndromes and symptoms (Figure 1).

Mechanism of urgency incontinence

The literature attributes physiological disturbances to be the probable cause of urgency incontinence. There are three main aetiological domains which account for urgency incontinence, these being detrusor overactivity, poor detrusor compliance and bladder hypersensitivity. Detrusor overactivity is described as the unprompted, uninhibited contraction of the detrusor muscle, which coincides with the feeling of urgency and if this pressure overcomes that of the urinary sphincter, results in urgency incontinence [3] Detrusor overactivity is heralded as a multifactorial phenomenon with two main hypotheses proffering an explanation to its development. The first being the neurogenic hypothesis which states that the pathophysiology of detrusor overactivity is anatomically oriented to the spine and the parasympathetic motor supply to the bladder [7]. The second is the myogenic hypothesis which links detrusor overactivity to heightened contractility of the detrusor muscle cells [3]. Sometimes both neurogenic and myogenic mechanisms can coexist, but for some women the cause is idiopathic [3]. Poor detrusor compliance is also a possible cause of urgency incontinence as the failure of the bladder to stretch results in increased pressure, diminished capacity of the bladder and possible incontinence [3]. This phenomenon is common after pelvic radiotherapy and prolonged catheterization. The final possible cause of urgency incontinence is bladder hypersensitivity where the urothelium has a heightened sensory response to chemical, thermal and mechanical stimuli, augmenting detrusor function [8]. Increasing focus has been devoted to the urothelial response to infection and inflammation. Historically, urine was considered to be sterile, but with the advent of quantitative urine culture and gene sequencing of bacteria, our understanding has evolved such that commensal organisms may exist in the bladder [9]. It is thought that an imbalance in the microbiota of the bladder may trigger urothelial hypersensitivity which could result in urgency incontinence [3].

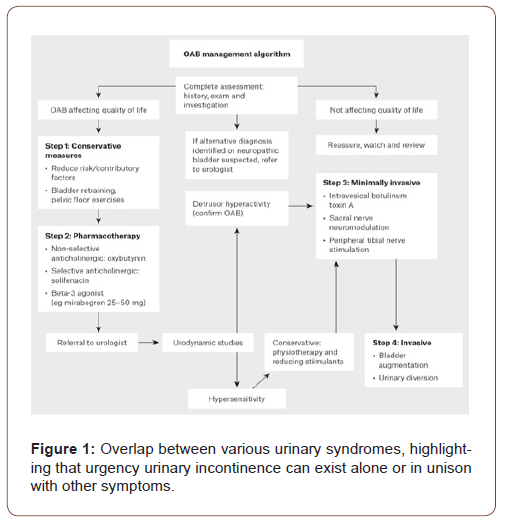

Management

Management of urinary incontinence is determined by the type and severity of the incontinence. It is an iterative process that begins by conservative management, followed by medical and surgical management. Conservative strategies include weight loss, fluid optimization, pelvic floor exercises and bladder training. Generally, after exhausting lifestyle, behavioural and physical therapy interventions, pharmacological and surgical treatments are pursued. Figure 2 demonstrates the general management approach of urgency incontinence experienced with overactive bladder syndrome [10]. Recently, laser therapy has risen in prominence in the literature as a potential novel, non-invasive treatment for Figure 1: Overlap between various urinary syndromes, highlight- female urgency urinary incontinence (Figure 2).

Laser therapy

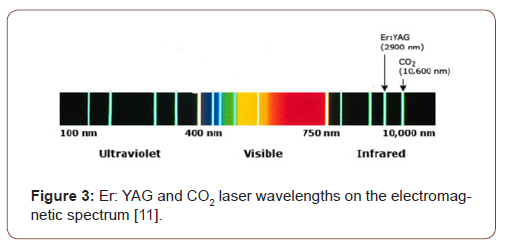

Lasers are used in a variety of specialities and clinical settings and have multiple purposes such as for the cutting, ablation, coagulation or imaging of tissues. Lasers work by emitting radiation in a single, coherent manner. The radiation is of a particular wavelength and can operate in the infrared, visible and ultraviolet portions of the electromagnetic spectrum. In the treatment of female urinary incontinence there are two types of lasers which have been described and tested in the literature. These are the Erbium YAG (Er:YAG) and the CO2 laser. Both lasers are in the infrared part of the electromagnetic spectrum [11] (Figure 3) and target the subepithelial collagen and aim to induce remodelling and restructuring, for which histological evidence demonstrates success [12,13] (Figure 3).

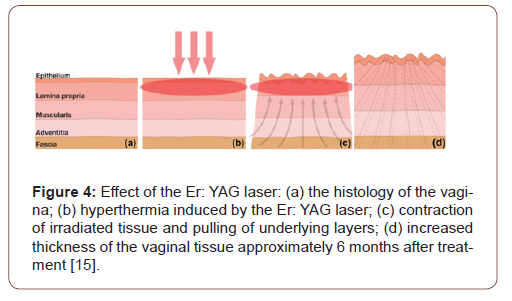

The CO2 laser causes a micro-ablative thermal effect resulting in the expression of heat shock proteins which aim to restore the natural architecture that existed before the incitement of the stress [14] This is done by the synthesis of extracellular matrix, collagen and elastic fibres. The Er:YAG laser causes a non-ablative thermal effect resulting in hyperthermia of the vaginal collagen, causing contraction of the irradiated tissue and mechanical pulling of the underlying layers. This results in remodelling and synthesis of new collagen fibres improving the tightness and elasticity of the tissue [15] (Figure 4).

Hypothesis

Laser therapy may be a valid option for those women who are experiencing hypoestrogenic vaginal atrophy related urinary incontinence since the mechanism of the laser is to increase collagen production, similar to topical estrogen. It may also benefit women through its interaction with the microbiota of the bladder.

Methods

A search of PUBMED, MEDLINE and EMBASE databases were conducted between January and February 2021 with the following search terms: Female urinary incontinence, Laser, CO2, Er: YAG, Urge, Overactive bladder, Genitourinary syndrome of menopause, Mixed urinary incontinence. Relevant articles were collated by screening titles and abstracts. The search was limited to English papers with no restriction on publication year. Additionally, citation chaining was utilized to ensure that no landmark studies were missed.

Discussion of Evidence

There were no studies that examined the effect of laser therapy on urge incontinence by itself, rather the symptom of urge incontinence was grouped with overactive bladder or genitourinary syndrome of menopause and assessed accordingly. Even then there are limited studies in comparison to those assessing laser therapy in stress incontinence. The selected studies are presented based on the type of laser used.

CO2 laser

Perino et al. [16] published a pilot study in 2016, enrolling 30 menopausal women who had GSM, of which 8 8 reported urgency incontinence in addition to the other symptoms included in GSM. All patients received 3 treatment sessions with the laser over a period of 30 days. The mean score of the OAB-q-SF questionnaire decreased from 18 to 8. The patients experiencing urgency incontinence reported an improvement in their symptoms (reduction in daily episodes of incontinence) 30 days after the last laser application (p=0.006). Importantly, no adverse effects were noted [16]. Additionally, in 2016 a prospective observational study was done by Pitsouni et al. [17] where 53 women received intravaginal laser treatment once a month for three months to examine the difference this would make on GSM. The ICIQ Urinary Incontinence Short Form (ICIQ-UI SF) and the Urogenital Distress Inventory (UDI-6) were completed by patients at baseline and 4 weeks after the last laser session. For the 35 women experiencing urgency incontinence, their symptoms were shown to improve from baseline (p=0.001). No serious side effects were reported, only mild irritation of the introitus that resolved 2 hrs after the first laser treatment [17]. Aguiar et al. [18] conducted a randomised clinical trial in 2020 where 72 women were divided into three intervention groups; one received 3 treatments of CO2 laser 30-45 days apart, one received 10mg of vaginal promestriene (topical oestrogen) three times a week for 12 weeks and the final group used a vaginal lubricant gel. The International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire Overactive Bladder (ICIQ‐OAB) was completed by subjects before and 2 weeks after treatment. Although a reduction in urgency incontinence was demonstrated, it did not reach statistical significance in any of the three treatment groups, possibly due to the sample size. A study investigating the long-term efficacy, safety and feasibility of fractional CO2 laser on a cohort of 102 post-menopausal women was conducted by Behnia-Willison et al. [19] for GSM. It did however examine urgency incontinence as a secondary outcome. The laser was administered 3 times for each patient with an intervening period of 6 weeks or more. The Australian pelvic floor questionnaire was completed by patients before initial treatment, 2-4 months after the first treatment and then finally 12-24 months after the first treatment. The results demonstrated a statistically significant reduction in urgency incontinence (p<0.001). However, this is the first study that followed up patients to determine if any complications arise following treatment. They found that a small number of patients experienced urinary tract infections, abnormal discharge, lower pelvic pain and per vaginal bleeding [19].

Er: YAG laser

The first study to investigate the utility of Er: YAG lasers in urgency incontinence was published in 2015 by Ogrinc et al. [20] It divided 175 women into two groups based on their type of incontinence: stress or mixed urinary incontinence. The ICIQ-SF was used as the evaluation of symptoms at 2, 4 and 12 months after the final treatment (2 or 3 laser sessions). The results showed that the severity of the incontinence improved for all patients, but it was more effective for SUI compared to MUI, with only 34% of women (in the MUI group) stating that they no longer experience urinary incontinence [20]. Despite seemingly positive results, the therapy does not seem as efficacious for MUI and therefore may not translate to other syndromes that contain urgency incontinence. A study performed in 2017 by Lin et al. [21] enrolled 30 women with symptoms of OAB and urinary incontinence and examined their response to treatment with Er: YAG laser. They received two laser sessions four weeks apart and the Overactive Bladder Symptom Score (OABSS) questionnaire was used to assess their symptoms at baseline and then at 3 and 12 months after treatment. Although the symptom scores improved at the 3-month follow up (p=0.027), these results were not maintained at the 12 months checkup (p=0.576).21 This may be because only two laser sessions were provided to the subjects or because the intervening time between the sessions was not long enough to produce long-lasting results. In 2019, Okui [22] performed a comparative study between sling procedures (transvaginal and transobturator tape) and Er:YAG laser for SUI and MUI. The laser group had 3 treatments every other month. Results after 12 months demonstrated comparable improvements for incontinence in all 3 groups inidicated by the 1h-pad test and the ICIQ-SF. However, only the laser group had improvements for MUI (p<0.001) according to the OABSS [22]. Okui also published another study in 2019 comparing the Er:YAG laser to the standard therapy for OAB [23] There were three arms to the study, one group receiving 3 treatments of the laser (one month apart), the second group received anticholinergic (4 mg fesoterodine once daily) and the last group received beta3-adrenoreceptor agonist (25 mg mirabegron once daily). The OABSS was completed 12 months after the start of therapy and it demonstrated a significant improvement in score compared to baseline levels for all three arms of the study (p<0.001). The author argued that the laser group had comparable results to the current medical regimen without the side-effects of constipation and mouth dryness and heralded that it will eventually supersede pharmacological treatment in the future.

Limitations and future directions

There is a paucity of research investigating the effect of both CO2 and Er: YAG laser therapies for urgency incontinence. Those which are available are mostly single centre studies with small sample sizes, lack of control groups with short term follow-ups only. There are currently no randomised controlled trials researching lasers and urgency incontinence. Thus, there is a need for large multicentred, placebo controlled double blinded randomised controlled trials. There is also the need to establish the long-term efficacy, safety and complication profiles of both lasers. Additionally, there is no current consensus on the standard laser delivery parameters and the number of sessions required to achieve an adequately lasting response. Finally, there needs to be cost-effectiveness studies which will provide a health economic perspective on the implementation of lasers, particularly in the public system. Future studies should focus on elucidating the microbiology of the bladder and urinary system and determine if laser therapy has any effect on this, correlating this with symptomatic changes. There need to be more studies which compare laser therapy with the current best practice, but also determine if there is any utility in combining the current treatment(s) with laser therapy.

Conclusion

Overall, both CO2 and Er:YAG lasers are promising therapies that may be able to curtail the distress and morbidity caused by urgency urinary incontinence. At the present time, however, there is not enough evidence to approve of the efficacy, safety and thus implementation of lasers in the Australian healthcare system for treatment of urgency urinary incontinence.

Acknowledgement

None.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest.

References

- Haylen BT, De Ridder D, Freeman RM, Swift SE, Berghmans B, et al. (2010) An international urogynecological association (IUGA)/international continence society (ICS) joint report on the terminology for female pelvic floor dysfunction. Neurourol Urodyn 29(1): 4-20.

- Ashton-Miller JA, Delancey JOL (2007) Functional Anatomy of the Female Pelvic Floor. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1101: 266-296.

- Aoki Y, Brown HW, Brubaker L, Cornu JN, Daly JO, et al. (2017) Urinary incontinence in women. Nat Rev Dis Primers 3: 17042.

- Health AIo and Welfare (2013). Incontinence in Australia. Canberra: AIHW.

- Sims J, Browning C, Lundgren-Lindquist B, Hal Kendig (2011) Urinary incontinence in a community sample of older adults: prevalence and impact on quality of life. Disabil Rehabil 33(15-16): 1389-1398.

- Shifren JL (2018) Genitourinary Syndrome of Menopause. Clin Obstet Gynecol 61(3): 508-516.

- Roosen A, Chapple CR, Dmochowski RR, Fowler CJ, Gratzke C, et al. (2009) A Refocus on the Bladder as the Originator of Storage Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms: A Systematic Review of the Latest Literature. Eur Uro 56(5): 810-819.

- Reid G, Burton JP (2016) Making sense of the urinary microbiota in clinical urology. Nat Rev Urol 13(10): 567-568.

- Hilt EE, McKinley K, Pearce MM, Rosenfeld AB, Zilliox MJ, et al. (2014) Urine Is Not Sterile: Use of Enhanced Urine Culture Techniques To Detect Resident Bacterial Flora in the Adult Female Bladder. J Clin Microbiol 52(3): 871-876.

- Hutchinson A, Nesbitt A, Joshi A, Clubb A, Perera M (2020) Overactive bladder syndrome: Management and Treatment Options. Aust J Gen Pract 49(9): 593-598.

- Colt H (2021) Basic principles of medical lasers. Waltham, MA: Up To Date.

- Lapii GA, Yakovleva AY, Neimark AI (2017) Structural Reorganization of the Vaginal Mucosa in Stress Urinary Incontinence under Conditions of Er:YAG Laser Treatment. Bull Exp Biol Med 162(4): 510-514.

- González Isaza P, Jaguszewska K, Cardona JL (2018) Long-term effect of thermoablative fractional CO2 laser treatment as a novel approach to urinary incontinence management in women with genitourinary syndrome of menopause. International Urogynecology Journal 29: 211-215.

- Walter JE, Larochelle A (2018) No. 358-Intravaginal Laser for Genitourinary Syndrome of Menopause and Stress Urinary Incontinence. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 40(4): 503-511.

- Vizintin Z, Lukac M, Kazic M, Tettamanti M (2015) Erbium laser in gynecology. Climacteric 18: 4-8.

- Perino A, Cucinella G, Gugliotta G, S Polito, B Adile, et al. (2016) Is vaginal fractional CO2 laser treatment effective in improving overactive bladder symptoms in post-menopausal patients? Preliminary results. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 20(12): 2491-2497.

- Pitsouni E, Grigoriadis T, Tsiveleka A, Dimitris Zacharakis, Stefano Salvatore, et al. (2016) Microablative fractional CO2-laser therapy and the genitourinary syndrome of menopause: An observational study. Maturitas 94: 131-136.

- Aguiar LB, Politano CA, Costa‐Paiva L, Juliato CRT (2020) Efficacy of Fractional CO2 Laser, Promestriene, and Vaginal Lubricant in the Treatment of Urinary Symptoms in Postmenopausal Women: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Lasers in Surg Med 52(8): 713-720.

- Behnia-Willison F, Sarraf S, Miller J, Behrang Mohamadi, Alison S Care, et al. (2017) Safety and long-term efficacy of fractional CO2 laser treatment in women suffering from genitourinary syndrome of menopause. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 213: 39-44.

- Ogrinc UB, Senčar S, Lenasi H (2015) Novel minimally invasive laser treatment of urinary incontinence in women. Lasers in Surg Med 47(9): 689-697.

- Lin YH, Hsieh WC, Huang L, Liang CC (2017) Effect of non-ablative laser treatment on overactive bladder symptoms, urinary incontinence and sexual function in women with urodynamic stress incontinence. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol 56(6): 815-820.

- Okui N (2019) Comparison between erbium-doped yttrium aluminum garnet laser therapy and sling procedures in the treatment of stress and mixed urinary incontinence. World J Urol 37(5): 885-889.

- Okui N (2019) Efficacy and safety of non-ablative vaginal erbium: YAG laser treatment as a novel surgical treatment for overactive bladder syndrome: comparison with anticholinergics and β3-adrenoceptor agonists. World J Urol 37(11): 2459-2466.

-

Ali Abid, Emmanuel Karantanis. Evaluation of Laser Therapy for Urgency Urinary Incontinence in Females. Annal Urol & Nephrol. 2(5): 2021. AUN.MS.ID.000546.

-

Female urinary incontinence, Laser, CO2, Er: YAG, Urge, Overactive bladder, Genitourinary syndrome of menopause, Mixed urinary incontinence

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.