Case Report

Case Report

Central Migration of Tunneled Dialysis Catheter into Right Ventricle causing Positional Superior Vena Cava Obstruction: A Case Report

Muhammad U Sharif* and Kottarathil A Abraham

Department of Nephrology, Aintree University Hospital, Liverpool, United Kingdom

Dr Muhammad U Sharif, Renal Medicine speciality Trainee, Aintree University Hospital, Longmoor Lane, L9 7AL Liverpool, United Kingdom.

Received Date: November 24, 2020; Published Date: December 16, 2020

Abstract

Tunneled dialysis catheters placement under real-time ultrasound guidance using the internal jugular route is considered to be a relatively simple and straightforward procedure, though its insertion and maintenance are not entirely risk-free. A literature search is full of reports describing various complications dialysis catheters placement; however, a central displacement of the catheter months after insertion is not described in the past. This case report highlights a case of the central migration of tunneled dialysis catheters and emphasizes the importance of close monitoring of the position of these catheters.

Introduction

The invention of tunneled dialysis catheters, more than three decades ago, has revolutionized vascular access in hemodialysis patients [1]. Over the years, it has become an integral part of the management of patients on hemodialysis and is used in up to a third of such patients, mostly as a bridge to more permanent dialysis access [2,3]. Right internal jugular (RIJ) vein catheterization under real-time ultrasound guidance is a relatively low-risk procedure and is considered the site of choice for tunneled dialysis catheter placement. For best results and to ensure optimal blood flow, it is recommended that the tip of a tunneled dialysis catheter should be positioned at the junction of superior vena cava (SVC) and right atrium or into the right atrium [4,5]. It has been advised not to place the dialysis catheter too deep into the right atrium to avoid potential complications [6,7]. Incorrect positioning of a hemodialysis catheter is relatively uncommon and rarely described. Previous case studies have described the misplacement of central venous catheters or hemodialysis catheter into the azygous vein [8], accessory hemiazygous vein [9], brachiocephalic vein, subclavian vein [10], brachiocephalic artery [11], mediastinum [12], pleural space [13], left atrium [14] and pericardium [15]. Catheter misplacement can happen at the time of insertion or after a while due to the migration of the tip. Although it is not uncommon for a hemodialysis catheter to migrate peripherally and fall out, the central migration of a tunneled dialysis catheter into the right atrium and across the tricuspid valve into the right ventricle has not been described in literature before.

Case report

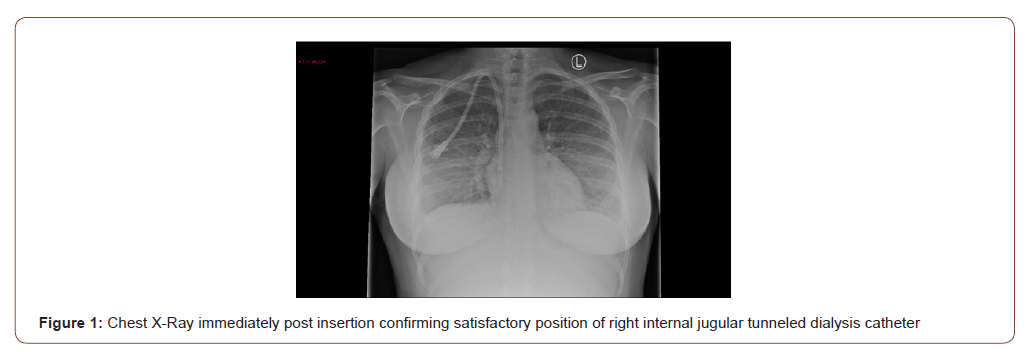

We report the case of a 35 years old woman who developed acute kidney injury (AKI) stage 3 and adult respiratory distress syndrome following severe postpartum hemorrhage. She required level 3 care including renal replacement therapy. Her anuric AKI failed to recover and she was transferred to the renal unit three days post-partum. A renal biopsy was undertaken and showed diffuse cortical necrosis. Her temporary dialysis catheter was removed and the next day, a PalindromeTM tunneled catheter (14.5 Fr, split-tip, 28 cm) was placed in her right internal jugular vein (RIJ) using a real-time ultrasound-guided approach. The position of the RIJ catheter was confirmed with a chest x-ray (Figure 1).

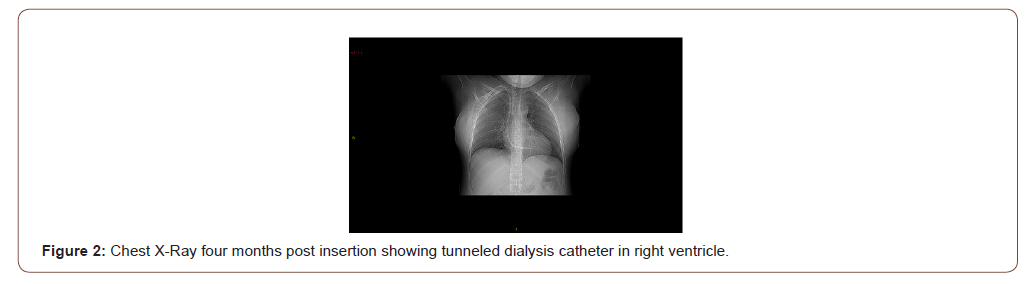

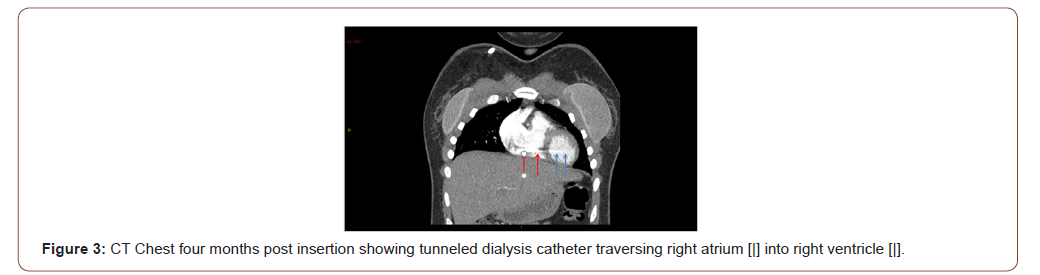

She was re-established on hemodiafiltration and discharged ten days later to continue outpatient renal replacement therapy (RRT). Plans were made for the medical placement of a peritoneal dialysis catheter once her uterus had involuted. The patient remained stable on satellite unit based hemodiafiltration until a week later she developed a mild persistent tachycardia and dyspnea on lying down. Her symptoms progressed into a cough and she was treated for pneumonia. A computed tomography [CT] angiogram of the pulmonary arteries was undertaken and excluded a pulmonary embolism. Patchy consolidation was noted, and the tip of the dialysis catheter was seen to lie in the right atrium. The patient remained well until four months later when flow through her dialysis catheter deteriorated. Urokinase infusion improved flows temporarily but the patient complained of worsening shortness of breath (SOB), dizziness, headaches, and flushing. The patient also noted intermittent swelling of her face and neck associated with the dyspnea but no orthopnea or paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea. Standing up from a lying or sitting posture worsened the swelling and occurred despite the absence of any dependent edema or increases in her interdialytic weight gains. A chest x-ray showed the tunneled dialysis catheter in an advanced position (Figure 2).

And a subsequent CT pulmonary angiogram confirmed the position of the RIJ tunneled dialysis catheter crossing the tricuspid valve with the tip in the right ventricle (Figure 3).

She underwent a successful manipulation of the catheter under radiological guidance that resulted in the complete resolution of all the symptoms.

Discussion

Peripheral migration of the central venous catheters is a commonly documented event and is described in up to 17% on individuals after percutaneous catheter insertion [16,17]. However central migration to right atrium floor or right ventricle is extremely uncommon and not been described in terms of tunneled hemodialysis catheters. Such migration can lead to potentially serious complications of atrial mural thrombus, perforation, arrhythmias, and cardiac tamponade, as has been noted with central venous catheters outside the dialysis setting [6,7,18]. Symptoms of positional headaches, dyspnea and flushing have been attributed to advanced superior vena cava (SVC) obstruction [19] and have also been described in the context of positional SVC obstruction secondary to pacemaker implantation in the past [20]. However, SVC syndrome has not been described previously in relation to a hemodialysis catheter. Another unusual feature of this case is that symptoms only developed four months after the insertion of the hemodialysis catheter suggesting that the migration occurred only then. The time sequence suggests that either the anchoring of the tunneled catheter by fibrosis into the cuff had not taken place from the start or had broken down in that period. It is important to note that our patient did not develop any exit site, tunnel or line infections that could have contributed to the failure of the cuff tethering. In summary, our patient developed SVC syndrome because of the central migration of the hemodialysis catheter causing blockage of the blood flow across her tricuspid valve. The presence of the positional symptoms of worsening dyspnea, dizziness, headaches, flushing and/or facial swelling in hemodialysis patients with dialysis lines should raise suspicion of SVC obstruction prompting urgent investigations for thrombosis or line migration. In the case of malposition, timely manipulation or replacement of the migrated dialysis catheter will resolve the problem without sequelae.

Acknowledgment

None.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest.

References

- Schwab SJ, Buller GL, McCann RL, Bollinger RR, Stickel DL (1988) Prospective evaluation of a Dacron cuffed hemodialysis catheter for prolonged use. American journal of kidney diseases the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation 11(2): 166-169.

- Rayner HC, Pisoni RL (2010) The increasing use of hemodialysis catheters: evidence from the DOPPS on its significance and ways to reverse it. Seminars in dialysis 23(1): 6-10.

- Aitken EL, Stevenson KS, Gingell-Littlejohn M, Aitken M, Clancy M, et al. (2014) The use of tunneled central venous catheters: inevitable or system failure. The journal of vascular access 15(5): 344-350.

- (2001) III. NKF-K/DOQI Clinical Practice Guidelines for Vascular Access: update 2000. American journal of kidney diseases the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation 37(1): S137-S181.

- (2006) Clinical practice guidelines for vascular access. American journal of kidney diseases: the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation 48 (1): S248-S273.

- Vesely TM (2003) Central venous catheter tip position: a continuing controversy. Journal of vascular and interventional radiology J VascIntervRadiol 14(5): 527-534.

- Morgan D, Ho K, Murray C, Davies H, Louw J (2012) A randomized trial of catheters of different lengths to achieve right atrium versus superior vena cava placement for continuous renal replacement therapy. American journal of kidney diseases: the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation 60(2): 272-279.

- Jesús C, Juan B, Lucía M, Beatriz M, R PJ (2013) Recognizing misplacement of a dialysis catheter in the azygos vein. Hemodialysis International 17(3): 455-457.

- Ali MA, Raikar K, Kishore A (2015) A case of misplaced permacath dialysis catheter. Indian journal of critical care medicine: peer-reviewed, official publication of Indian Society of Critical Care Medicine 19(8): 490-492.

- Bekele NA, Abebe WA, Shifa JZ (2017) Misplaced subclavian central venous catheter. The Pan African Medical Journal 27: 59.

- Matsushita T, Huynh AT, James A (2006) Misplacement of hemodialysis catheter to brachiocephalic artery required urgent sternotomy. Interactive Cardiovascular and Thoracic Surgery 5(2): 156-158.

- Tong MK, Siu YP, Ng YY, Kwan TH, Au TC (2004) Misplacement of a right internal jugular vein haemodialysis catheter into the mediastinum. Hong Kong medical journal = Xianggangyixue za zhi 10(2): 135-138.

- Kumar M, Singh A, Sidhu KS, Kaur A (2016) Malposition of Subclavian Venous Catheter Leading to Chest Complications. Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research JCDR 10(5): PD16-PD18.

- Balasubramanian S, Gupta S, Nicholls M, Laboi P (2014) Rare complication of a dialysis catheter insertion. Clinical Kidney Journal 7(2): 194-196.

- Booth SA, Norton B, Mulvey DA (2001) Central venous catheterization and fatal cardiac tamponade. BJA: British Journal of Anaesthesia 87(2): 298-302.

- Paw H (2002) Bilateral pleural effusions: unexpected complication after left internal jugular venous catheterization for total parenteral nutrition. British journal of anaesthesia 89(4): 647-650.

- Thomas CJ, Butler CS (1999) Delayed pneumothorax and hydrothorax with central venous catheter migration. Anaesthesia 54(10): 987-990.

- Collier PE, Goodman GB (1995) Cardiac tamponade caused by central venous catheter perforation of the heart: a preventable complication. Journal of the American College of Surgeons 181(5): 459-463.

- Rice TW, Rodriguez RM, Light RW (2006) The superior vena cava syndrome: clinical characteristics and evolving etiology. Medicine 85(1): 37-42.

- Biria M, Gupta R, Lakkireddy D, Gupta K (2009) Recurrent positional syncope as the primary presentation of superior vena cava syndrome after pacemaker implantation. Heart rhythm 6(1): 144-145.

-

Muhammad U Sharif, Kottarathil A Abraham. Central Migration of Tunneled Dialysis Catheter into Right Ventricle causing Positional Superior Vena Cava Obstruction: A Case Report. Annal Urol & Nephrol. 2(3): 2020. AUN.MS.ID.000540.

-

Tunneled dialysis catheters, Emphasizes, Hemodialysis, Right internal jugular, Superior vena cava, Kidney injury, Computed tomography, Shortness of breath

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.