Mini review

Mini review

Diabetic Nephropathy and Periodontal Disease: A Review and Update

Christopher Turner*

Turner MSc, BDS, MDS, FDSRCS, FCGDent, QDR, Specialist in Restorative Dentistry (Rtd) Bath UK

Christopher Turner, Turner MSc, BDS, MDS, FDSRCS, FCGDent, QDR, Specialist in Restorative Dentistry (Rtd) Bath UK

Received Date:April 29, 2025; Published Date:May 16, 2025

Abstract

Recent research has highlighted the importance of periodontal disease for patients with diabetic nephropathy. Periodontal disease (PD) was thought to be the sixth complication of diabetes mellitus (DM) because this latter group of patients has a 3 – 4 times greater risk of developing PD when compared with non-diabetics. This rises to 10 times for smokers. DM and PD are inter-related, one disease affecting the other and vice versa. The exact mechanism is probably related to inflammation as similar blood markers are raised in both diseases, the dental origin of which is from micro-organisms in mature dental plaque. From the medical point of view there are five complications of DM namely renal, cardiac, vascular, ophthalmic and neurological that can be visualized as a simple hub called DM with spokes for the above complications. However, the evidence has shown that the severity of all these five complications is worse when patients have active, uncontrolled PD. When PD is treated, there is an improvement in glycaemic control and the prognosis for end-stage renal disease can improve. Good oral hygiene is a critical component of glycaemic control. These results have led to the conclusion that PD is not a separate complication of DM but a co-morbidity factor acting by modifying the severity of another disease and modulating the severity of diabetic complications in the manner of a volume switch. A new model is proposed together with a system for doctors and dentists to work together because when DM and PD are treated together there may be a synergistic effect.

Keywords:Diabetic nephropathy; periodontal disease; diabetes mellitus; renal histology; pathophysiology

Introduction

The concept that periodontal disease was the sixth complication of diabetes mellitus (DM) and the increased risk that people living with diabetes had of developing periodontal disease (PD) dates back to 1999 [1]. However, the first description of this was much earlier in 1928 and forgotten [2]. We now know that this risk is about 3-4 times greater than for non-diabetics, rising to 10 times for diabetics who smoke [3]. In relation to renal disease: For type 1 diabetics, 10 per cent of the case load, 30 per cent are expected to develop nephropathy and this is seen in younger patients. For type 2 diabetics, 90 per cent of the case load, 50 per cent are expected to develop nephropathy and these are older patients. The comorbidities of hypertension and cardiovascular disease are common additional findings. The severity of renal complications depends upon their duration, the level of glycaemic control and genetic factors. These factors also increase the risk of developing PD in Afro-Caribbean and Indian communities.

Renal Histology in Diabetes

After about 15 years structural changes occur in the glomeruli

due to long-standing hyperglycaemia and formation of advanced

glycated end products:

a) Diffuse uniform thickening of the glomerular basement

membrane.

b) Matrix expansion encroaching on the capillary lumina

that may be diffuse, nodular or both.

c) Micro aneurysms of glomerular capillaries develop due to

mesangiolysis.

d) Vascular hyalinosis is a common finding.

Pathophysiology

From the medical point of view there are five complications of diabetes mellitus namely, renal, cardiac, vascular, ophthalmic and neurological. We can visualize this simply as a hub called diabetes mellitus with spokes for the above five complications. Where does periodontitis fit in? Is it another spoke? The evidence is overwhelming that diabetes and periodontitis are interrelated, one disease affecting the other and vice versa [4,5], so the model relationship has to have both diabetes and periodontitis at a much larger hub with an inter-relationship (Figure 1). It follows that PD cannot be a spoke or complication and there is an alternative explanation of its role in relation to DM [6,7]. More importantly, the research evidence has shown that the severity of all these five diabetic complications is worse when patients have active, uncontrolled periodontitis. Also, when periodontitis is treated, there is an improvement in glycaemic control [8]. Good oral hygiene is a critical component of glycaemic control in diabetic patients [9].

The relationship between DM and PD is thought to be inflammatory in origin. There is a common pathogenesis involving an enhanced inflammatory response at both local and systemic levels [10]. This is caused by the chronic effects of hyperglycaemia and the formation of advanced glycation end-products that promote the inflammatory response [10]. Levels of C-reactive protein [4], and cytokines [11] are raised in both diseases. The inflammatory origin in PD is from Gram negative organisms in mature dental plaque because polysaccharides in Gram negative bacteria in this plaque are known to stimulate the production of cytokines, and when dental plaque is left in situ, after seven to ten days gingival inflammation ensues and this is the precursor of periodontitis [12]. PD may be thought of as an infection. However, it is not in the true medical sense of the word because it does not meet Koch’s postulates for a single recoverable infective agent. PD is a chronic hyper sensitivity reaction to antigens in mature dental plaque.

Research has shown that when the severity of diabetic complications is compared to periodontal status that for:

Nephropathy

People on dialysis are at greater risk of developing PD [13] and other oral manifestations and have increased oral health problems [14]. In a Japanese study 40 per cent of dialysis patients had diabetic nephropathy, a lower glomerular filtration rate with a higher Community Periodontal Index of Treatment Needs (CPITN) and a positive correlation between the CPITN score and serum creatinine. With severe Periodontitis there is a 2.6 times greater risk of macroglobinaemia and a 4.9 times risk of end stage renal disease [14]. Periodontal management may contribute to the prevention of renal disease [15] as it has an effect on end-stage renal disease [16]. Patients should be screened for periodontitis before acceptance onto dialysis programmes [17].

Cardiac and Vascular

Poor oral health is associated with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. This interaction raises cardiac morbidity fourfold and is associated with chronic infection mediators which may lead to the initiation of endothelial dysfunction [18] which could also affect the renal endothelium.

Neuropathy

Is a microvascular complication for example, there is an inverse relationship between salivary flow and glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) levels that may be due to disturbances in glycaemic control [19].

Retinopathy

There are few studies of this complication [20,21]. However, an increase in the severity of diabetic retinopathy is associated with the components of periodontal disease [22].

From this evidence it is clear that periodontitis is influencing

of diabetic’s individual responses and medical complications. It is

both:

a) Modifying the severity of another disease.

b) And modulating the severity of diabetic complications in

the manner of a rheostat, the greater the level of periodontal

disease, the worse the complications at one end of the

spectrum, while when PD is successfully treated glycaemic

control improves at the other.

This is a new concept and means that PD should not be regarded as a complication of DM but a co-morbidity factor. Therefore, for optimum treatment of people living with diabetes there has to be both medical and dental contemporaneous input into their care. When both are treated together there may be a synergistic effect [23]. In summary, the new model shows dentists can support doctors and their diabetic patients and improve outcomes. There is a need for a paradigm shift in thinking and better interprofessional co-operation in care [24,25]. One method may be a traffic light risk assessment form for both diseases that people living with diabetes can share with their professional advisors.

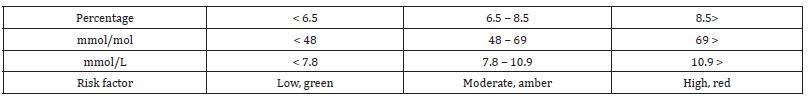

Defining Risk Factors for Doctors

The medical gold standard for diabetic monitoring is the serum level of glycated haemoglobin, the HbA1c. This may be recorded as percentage levels that should be maintained below 6.5%, green on the traffic light method above [26,27]. There is an amber band for 6.5 to 8.5% and a red band for greater than 8.5% (Table 1).

Table 1:HbA1c levels and medical risks.

Defining Risk Factors for Dentists

The measure of choice is the World Health Organisation’s (CPITN) [28]. The mouth is divided into sextants with scores given for pocket depth measurement, bleeding on probing or calculus. The maximum score recorded of the six gives a periodontal risk factor using the traffic light system,0,1, or 2, green, 2* or 3, amber, and 4 0r 4* as red (Table 2). A pro forma has been developed for people living with diabetes to record their results and share them with their respective professional advisors (Table 3) [24]. This form is freely downloadable at www.chooseabrush.com.

Table 2:Periodontal risk factor.

Discussion

Periodontitis predicts the development of overt nephropathy and ESRD in a dose dependent manner in individuals with little or no pre-existing kidney disease [29]. Periodontal management can contribute to the prevention of severe renal disease [15]. Good oral hygiene is a critical component of glycaemic control in diabetic patients [17]. It follows that that all patients with diabetic nephropathy should have periodontal screening and where appropriate, periodontal treatment for this preventable disease because this can reduce the need for diabetic medication. Doctors may be unaware of the link between DM and PD and are not asking patients what dental care they might, or might not be receiving. On present evidence, people living with diabetes will be placed at a disadvantage. Doctors need to understand basic facts about periodontitis and record which of their patients is receiving dental care and advise those who are not that they are at greater risk of developing PD and that when PD is treated their blood sugar levels can be better controlled [30,31].

Dentists need to understand the importance of HbA1c scores and add these to their patient’s medical histories [32]. In our recent study, asking this question in general dental practice 28 per cent did not know. And 12 per cent were in the red zone [33].

The importance here is that as the HbA1c increases, bringing PD under control becomes harder. Fortunately, periodontitis is both a treatable and preventable disease with good clinical outcomes when detected at an early stage. Prevention depends on daily efficient and effective plaque control by patients [7,34]. When plaque is left in situ for 7 to 10 days inflammation results [12]. Where these is bone loss between teeth and gingivae the most efficient way to remove plaque is by using interdental brushes. For ideal results an individual prescription for the correct diameter brush for each space is essential as in one study every patient had a unique pattern of bone loss and therefore brush diameter requirements were highly individual [34].

If plaque is not removed effectively and efficiently on a daily basis, it will continue to contribute to the bacteriological load, periodontal disease will continue and diabetic complications are less likely to be limited. This means that the critical component in glycaemic control, good oral hygiene, will not be achievable [9].

Conclusions

PD is not the sixth complication of DM. It modifies and modulates the severity of diabetic complications. This means that both diseases should be treated concurrently and that dentists and their teams have a very important role to play together with doctors. Risk results need to be shared between doctors and dentists. A form has been developed for patients themselves to show their respective professional advisors. This can be downloaded at www. chooseabrush.com. The glycated haemoglobin results, HbA1c are essential for dentists. The higher the score the more difficult it is to control periodontal disease.

Declaration of Interest

The author is the inventor of the Chooseabrush® method of interdental plaque control.

References

- Löe H (1993) Periodontal disease. The sixth complication of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care 16: 329, 1999. Periodontal disease. The sixth complication of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care 16(1): 329-334.

- Williams J B (1928) Diabetic periodontoclasia. J Amer Dent Assoc 15: 523-529.

- Battancs E, Georghita D, Nyiraty S, Lengyel C, Eördegh G, et al. (2020) Periodontal disease in diabetes mellitus: A case-controlled study in smokers and non-smokers 11(11): 2715-2728.

- Southerland JH, Taylor GW, Offenbacher S (2005) Diabetes and Periodontal Infection: Making the Connection. Clinical Diabetes 23(4): 171-178.

- Stöhr J, Barbaresko J, Neuenschwander M, Schlesinger S (2021) Bidirectional association between periodontal disease and diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Scientific Reports 11(1): 13686.

- Turner CH (2025) Diabetes mellitus and its sixth complication explained. Int J Clin Case Rep and Reviews 24(4): 1-6.

- Turner CH (2025) Periodontal disease: A co-morbidity factor in diabetes mellitus. Int J Endocrinol Diabetes 8: 187192.

- Wang TF, Jen IA, Chou C (2014) Effects of periodontal therapy on the metabolic control of patients with type 2 diabetes and periodontal disease: a meta-analysis. Medicine Baltimore 93(28): e292.

- Miyuzawa I, Katsutaro M, Kayo H, Atsushi I, Shinji K (2025) The relationship among obesity, diabetes and oral health. A narrative review of world health evidence 12(1).

- Liu R, Bal HS, Desta T, Behl Y, Graves DT (2006) Tumor necrosis factor-alpha mediates diabetes-enhanced apoptosis of matrix-producing cells and impairs diabetic healing. The American Journal of Pathology 168(3): 757-764.

- Johnson Dr, O’Connor JC, Satpathy A, Freund GG (2006) Cytokines in type II diabetes. Vitam Horm 74: 405-441.

- Löe H, Theilade E, Jensen SB (1965) Experimental gingivitis in man. Journal of Periodontology 36:177-187.

- Nguyen ATM, Akhter R, Garde S, Scott C, Twigg SM, et al. (2020) The association of periodontal disease with the complications of diabetes mellitus. A systematic review. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 165:108244.

- Mahajan S, Bhaskar N, Kaur RK, Jain A (2021) A Comparison of oral health status in diabetic and non-diabetic patients receiving haemodialysis - a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Metab Syndr 15(5): 102256.

- Yoshioka M, Okamoto y, Murata M, Fukui M, anagisawa S, et al. (2020) Association between oral health status and diabetic nephrology- related indices in Japanese middle-aged men. J diabetes Res 7:2020:4042129.

- Shultis W, Weil EJ, Looker HC, Curtis JM, Shlossman M, et al. (2007) Effects of periodontitis on overt nephropathy and end stage renal disease in type 2 diabetics. J Diabetes care 30(2): 306-311.

- Miyata Y, Obata Y, Mochizuki Y, Kitamura M, Mitsunari k et al. (2019) Periodontal disdeases in patients receiving dialysis. Int J Mol Sci 20(15): 3085.

- Khumaedi AI, Purnamasari D, Wijaya P, Soeroso Y (2019) The relationship between diabetes, periodontal and cardiovascular disease. Diabetes Metab Syndr 13(2): 1675-1678.

- Moore PA, Weyant RJ, Mongelluzzo MB et al. (2001) Type 1 diabetes, xerostomia and salivary flow rates. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Path Oral Radiol Endodod 92(3): 281-291.

- Yamamoto Y, Morazumi T, Hirata T, Takahashi T, Fuchida S, et al. (2020) Effect of periodontal disease on diabetic retinopathy in type 2 diabetic patients. A cross-sectional pilot study. J Clin Med 92(10): 3234.

- Alverenga MOP, Miranda GHN, Ferriera RO, Saito MT, Fagundes NCF, et al. (2020) Association between diabetic retinopathy and periodontitis. A systematic review. Front Public Health 8: 550614.

- Tandon A, Kamath YS, Gopalkrishna MB, Saokar A, Prakash S, et al. (2021) The association between diabetic retinopathy and periodontal disease. Saudi J Ophthalmol 34(3): 167-170.

- Turner CH (2023) Periodontal disease and diabetes mellitus. An update and case report. J Med Case Rep Case Series 4.

- Siddiqi A, Zafar S, Sharma A, Quaranta A (2022). Diabetes mellitus and periodontal disease: The call for inter-professional education and inter-professional collaborative care. J Interprof Care 36(1): 93-101.

- Turner CH (2024) Interprofessional Co-operation and result sharing between doctors, and dentists for people living with diabetes mellitus. ABC J Diab Endocrinol 9: 1-3.

- Turner CH (2022) Diabetes mellitus and periodontal disease: the profession’s choices. Brit Dent J 233(7): 537-538.

- Turner CH, Bouloux P-M (2023) Diabetes mellitus and periodontal disease: education, collaboration and information sharing between doctors, dentists and patients. Br J Diabetes 23: 35-38.

- Barmes D (1994) CPITN a WHO initiative. Int Dent J 44(5 Suppl 1): 523-525.

- Swapna LA, Sudhakara RR, Ramesh T, Lavanya R, Vijayalaxmi N, et al. (2013) Oral health status in haemodialysis patients. J Clin Diag Res 9: 2047.

- org.uk/guidance/NG17/chapter/recommendations NICE (2022). Recommendations | Type 1 diabetes in adults: diagnosis and management | Guidance | NICE.

- NICE.org.uk/guidance/NG28/chapter/recommendations NICE (2022) Recommendations | Type 2 Diabetes in adults: Management | Guidance | NICE.

- Turner CH (2024) An updated medical history form for people living with diabetes mellitus. Brit Dent J 237(4): 280-281.

- Goode SG, Turner CH (2024) Diabetes mellitus and periodontal disease: A pilot investigation into patient awareness of glycated haemoglobin levels and periodontal screening scores and their associated risk factors in general dental practice. Int J Diabetol Vascular Dis Res 11: 287-290.

- Turner CH (2011) Implant maintenance. The Dentist 62-64.

-

Christopher Turner*. Diabetic Nephropathy and Periodontal Disease: A Review and Update. Annals of Urology & Nephrology. 5(2): 2025. AUN.MS.ID.000606.

-

Diabetic nephropathy; periodontal disease; diabetes mellitus; renal histology; pathophysiology ; iris publishers; iris publisher’s group

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.