Case report

Case report

Case Report: Persistent Depressive Disorder Presenting as Chronic Fatigue in Primary Care

Yumna Riaz1*, Mehmood Qaisar2, Ushna Riaz3

1Department of Medicine, District Head Quarters Teaching Hospital, Gujranwala, Pakistan

2Department of Family Medicine, Medcare International Hospital, Gujranwala, Pakistan

3Department of Acute Medicine, Leicester Royal Infirmary, Leicester, UK

Yumna Riaz, Department of Medicine, District Head Quarters Teaching Hospital, Gujranwala, Pakistan

Received Date:July 01, 2025; Published Date:July 10, 2025

Abstract

Persistent Depressive Disorder (PDD), or dysthymia, is a chronic depressive condition that often presents with subtle mood symptoms and somatic complaints, making diagnosis challenging in primary care. We report the case of a 42-year-old woman with a two-year history of fatigue, body aches, and low mood, initially misattributed to physical illness. Comprehensive evaluation using standardized screening tools led to the diagnosis of PDD. Treatment with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) resulted in significant symptomatic improvement. This case highlights the importance of considering PDD in patients with chronic unexplained somatic symptoms and the critical role of family physicians in early recognition and management.

Keywords:Chronic fatigue; persistent depressive disorder (PDD); cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT); hallucinations

Introduction

Depression is one of the leading causes of disability worldwide, affecting individuals across diverse socioeconomic and geographic backgrounds. Despite growing awareness, milder and chronic forms of depression often remain overlooked in clinical practice. Persistent Depressive Disorder (PDD) is a chronic form of depression characterized by a consistently low mood lasting at least two years, often accompanied by symptoms such as low self-esteem, fatigue, and hopelessness [1,2]. It frequently goes underdiagnosed in primary care due to its subtle and insidious presentation [3]. The chronic fatigue associated with PDD can be mistaken for somatic complaints, especially in both resource-limited settings and highincome countries [4]. This case adds to the global clinical literature by illustrating the diagnostic challenges of PDD and emphasizing the importance of routine mental health screening in primary care across all healthcare systems.

Case Presentation

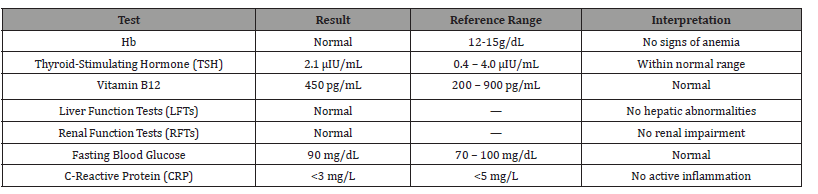

A 42-year-old female school teacher presented to a family medicine clinic with a two-year history of persistent fatigue, generalised body aches, low energy, and disturbed sleep. She had consulted multiple specialists, including internists, endocrinologists, and rheumatologists. Despite numerous investigations and empirical treatments (e.g., vitamin supplementation and sleep hygiene interventions), her symptoms persisted without improvement. All routine laboratory investigations, including a complete blood count (CBC), thyroid function tests, vitamin B12 levels, renal profile, liver enzymes, fasting blood glucose, and C-reactive protein (CRP), were within normal limits, effectively ruling out common metabolic or endocrine causes. These results are summarized in Table 1. Due to the absence of an identifiable organic cause and ongoing symptomatology, a psychosocial evaluation was performed. The patient reported a long-standing low mood, accompanied by hopelessness, diminished self-worth, anhedonia, social withdrawal, and poor concentration. She denied suicidal ideation, hallucinations, or recent psychosocial stressors. Her medical history included well-controlled hypothyroidism managed with levothyroxine. She was divorced, lived alone, and had no history of substance use.

Table 1:Laboratory Investigations.

To evaluate her psychological state, validated screening instruments were administered. The Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) score was 15, indicating moderate depression, while the Generalised Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) score was 6, consistent with mild anxiety. The PHQ-9 is a widely used nine-item tool aligned with DSM-5 criteria for diagnosing depressive symptoms [5]. The GAD-7 is a validated seven-item scale for assessing anxiety severity [6]. Pfizer Inc. copyrights both instruments and may be used for clinical and educational purposes without written permission when non-commercial [7]. Given the chronicity and persistence of symptoms for over two years, a diagnosis of Persistent Depressive Disorder (PDD) was established. The patient was started on sertraline 50 mg once daily and referred for cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT). She consented to a multimodal treatment plan and was scheduled for biweekly follow-ups. At her eight-week followup, the patient reported notable improvements in mood, energy levels, and social functioning. Her PHQ-9 score had decreased to 7, indicating mild depressive symptoms. She had resumed teaching duties and re-engaged with her social network [8].

Discussion

Persistent Depressive Disorder (PDD) often presents with vague and chronic physical complaints, such as fatigue, body aches, and sleep disturbances, which can easily be misattributed to physical illnesses, particularly in busy primary care settings. This subtle and insidious presentation contributes to frequent delays in diagnosis or even misdiagnosis [9]. Unlike Major Depressive Disorder (MDD), characterized by more acute and severe episodes, PDD tends to persist with low-grade symptoms over extended periods, causing patients to normalize their distress and avoid seeking mental health care. In this case, the patient initially consulted various specialists and underwent extensive investigations, including endocrinology and rheumatology screenings and routine laboratory tests. This pattern is common among patients with PDD, as they often experience somatic symptoms that prompt medical consultations before psychiatric evaluation is considered [10]. The eventual referral for psychiatric assessment underscores the critical importance of a holistic approach in primary care.

Family physicians play a pivotal role in identifying underlying mental health conditions when physical symptoms lack clear medical explanations. A thorough history-taking, combined with the use of validated screening tools such as the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) and Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7), is essential. In this case, the patient’s PHQ-9 score of 15 indicated moderate depression, while the GAD-7 score of 6 suggested mild anxiety, conditions that frequently coexist with depressive disorders. These scores helped guide clinical decision-making and justified the initiation of pharmacological and psychotherapeutic interventions. It was equally important to exclude medical mimics of fatigue and low energy. Normal vitamin B12 (450 pg/mL) and thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) levels (2.1 μIU/mL) ruled out common endocrine or nutritional causes, reinforcing a psychiatric origin for her symptoms [11]. The patient responded well to sertraline, a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI), combined with cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT). After eight weeks, her PHQ-9 score had decreased from 15 to 7, indicating significant clinical improvement.

This outcome aligns with prior meta-analytic evidence supporting the effectiveness of combined pharmacological and psychotherapeutic interventions for depressive disorders across varied populations [12]. This case highlights several important clinical lessons. First, PDD can easily go undiagnosed due to its nonspecific and chronic presentation. Second, primary care physicians must maintain a high index of suspicion for mood disorders when physical symptoms such as fatigue remain unexplained. Third, validated tools like PHQ-9 and GAD-7 should be routinely used to detect and monitor depression and anxiety. Ultimately, early diagnosis and a multimodal treatment approach can significantly enhance patient outcomes. By documenting this case, we aim to encourage more vigilant screening for PDD in patients presenting with somatic complaints. Increased awareness and structured mental health assessments in primary care settings could reduce diagnostic delays, lower healthcare costs, and improve overall patient well-being.

Conclusions

Persistent Depressive Disorder should be considered in patients with chronic fatigue and nonspecific somatic symptoms in primary care. Early recognition and combined therapeutic approaches can significantly improve patient outcomes. Family physicians play a pivotal role in bridging the gap between physical and mental healthcare. Raising awareness of subtle presentations of depression may improve early detection rates in primary care. Educating frontline physicians on the value of screening tools could also reduce diagnostic delays in mood disorders. Increased clinical vigilance can reduce misdiagnosis and improve the overall management of chronic mood disorders at the primary care level. This case highlights the importance of not dismissing persistent somatic complaints, as they may represent a deeper, ongoing mood disturbance.

References

- Schramm E, Klein DN, Elsaesser M, Furukawa TA, Domschke K (2020) Review of dysthymia and persistent depressive disorder: history, correlates, and clinical implications. Lancet Psychiatry 7(9): 801-812.

- Parker G, Malhi GS (2019) Persistent depression: should such a DSM‑5 diagnostic category persist? Can J Psychiatry 64(3): 177-179.

- Mitchell AJ, Vaze A, Rao S (2009) Clinical diagnosis of depression in primary care: a meta-analysis. Lancet 374(9690): 609-619.

- Simon GE, Von Korff M, Piccinelli M, Fullerton C, Ormel J (1999) An international study of the relation between somatic symptoms and depression. N Engl J Med. 341(18): 1329-1335.

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB (2001) The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med 16(9): 606-613.

- Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, Lowe B (2006) A brief measure for assessing generalised anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med 166(10): 1092-1097.

- Pfizer Inc (2022) Instructions and permissions for the PHQ and GAD-7 screeners. PHQ Screeners.

- Ravindran AV, Anisman H, Merali Z, Charbonneau Y, Telner J, et al. (1999) Treatment of primary dysthymia with group cognitive therapy and pharmacotherapy: clinical symptoms and functional impairments. Am J Psychiatry 156(10): 1608-1617.

- Smith CL, Alloy LB (2009) A roadmap to rumination: A review of the definition, assessment, and conceptualisation of this multifaceted construct. Clin Psychol Rev 29(2): 116-128.

- Kirmayer LJ, Groleau D, Looper KJ, Dao MD (2004) Explaining medically unexplained symptoms. Can J Psychiatry 49(10): 663-672.

- Munipalli B, Strothers S, Rivera F (2022) Association of vitamin B12, vitamin D, and thyroid-stimulating hormone with fatigue and neurologic symptoms in patients with fibromyalgia. Mayo Clin Proc Innov Qual Outcomes 6(4): 381-387.

- Cuijpers P, Dekker J, Hollon SD, Andersson G (2009) Adding psychotherapy to pharmacotherapy in the treatment of depressive disorders in adults: a meta-analysis. J Clin Psychiatry 70(9): 1219-1229.

-

Yumna Riaz*, Mehmood Qaisar, Ushna Riaz. Case Report: Persistent Depressive Disorder Presenting as Chronic Fatigue in Primary Care. Annals of Urology & Nephrology. 5(1): 2025. AUN.MS.ID.000607.

-

Chronic fatigue; persistent depressive disorder (PDD); cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT); hallucinations; iris publishers; iris publisher’s group

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.