Case Report

Case Report

Breaking Bad News: Addressing Hope, Spiritual Needs, And Denial to Achieve High Value Care

Kushinga Bvute1*, Samantha I Caballero2 and Alexander J Young3

1Internal Medicine Residency Program, Florida Atlantic University, USA

2Charles E Schmidt College of Medicine, Florida Atlantic University, USA

3Charles E Schmidt College of Medicine, Florida Atlantic University, USA

Kushinga Bvute, Internal Medicine Residency Program, Florida Atlantic University, Florida, USA.

Received Date: June 25, 2022; Published Date:August 15, 2022

Abstract

Keywords:Bad news; Denial; Spiritual needs; Communication; High value care; Prognosis

Abbreviations:PCP: Primary Care Physician; CT: Computed Tomography; MRI: Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Introduction

Breaking bad news to a patient in the hospital is a powerful experience for doctors in training [1] and is widely regarded as a demanding task for physicians [2]. One challenge for the admitted patient is the frequent handoffs; one provider initiates the conversation about the disease and prognosis while a different physician may provide the follow-up. Additionally, inpatient providers lack pre-existing longitudinal relationships with their patients and insight into their values, cultural, spiritual, and social issues, or the family support system. Thus, preparation for these conversations inside the hospital is more complex [3].

When disclosing bad news, the quality of the communication significantly influences the patients’ emotional adjustment and compliance with recommendations [4]. In addition, patients’ belief in miracles or denial may hinder prognostic discussions [5]. With the high cost of healthcare, providers are expected to practice high value care by improving communication and incorporating patient concerns and values into care plans. This case illustrates the challenges of revealing bad news, examines the patient’s responses, and provides recommendations to better prepare physicians for disclosing bad news.

Case Presentation

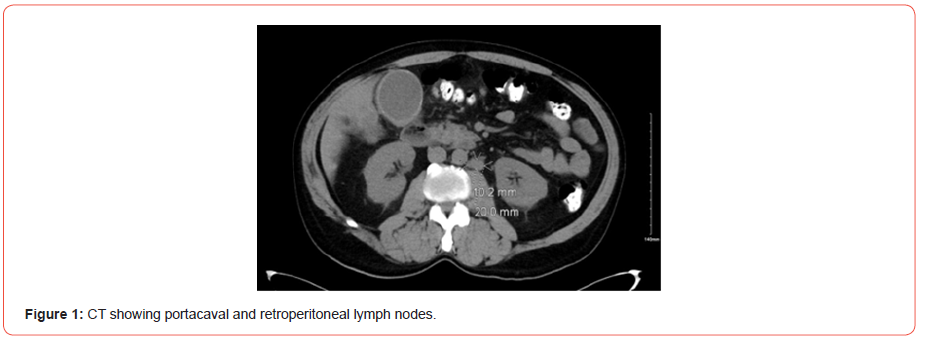

A 59-year-old Brazilian male presented to his primary care physician (PCP) with chronic epigastric pain. He was worked up for dyspepsia but continued to endorse intermittent diffuse abdominal pain as well as nausea and vomiting after dinner, so a right upper quadrant ultrasound was ordered, which showed multiple hypoechoic ill-defined mass lesions throughout the liver suspicious for metastatic disease and a gallbladder filled with sludge and stones. This prompted his PCP to send him to the hospital for a CT scan which showed multiple hepatic hypodense lesions, likely reflecting metastasis [Figure 1].

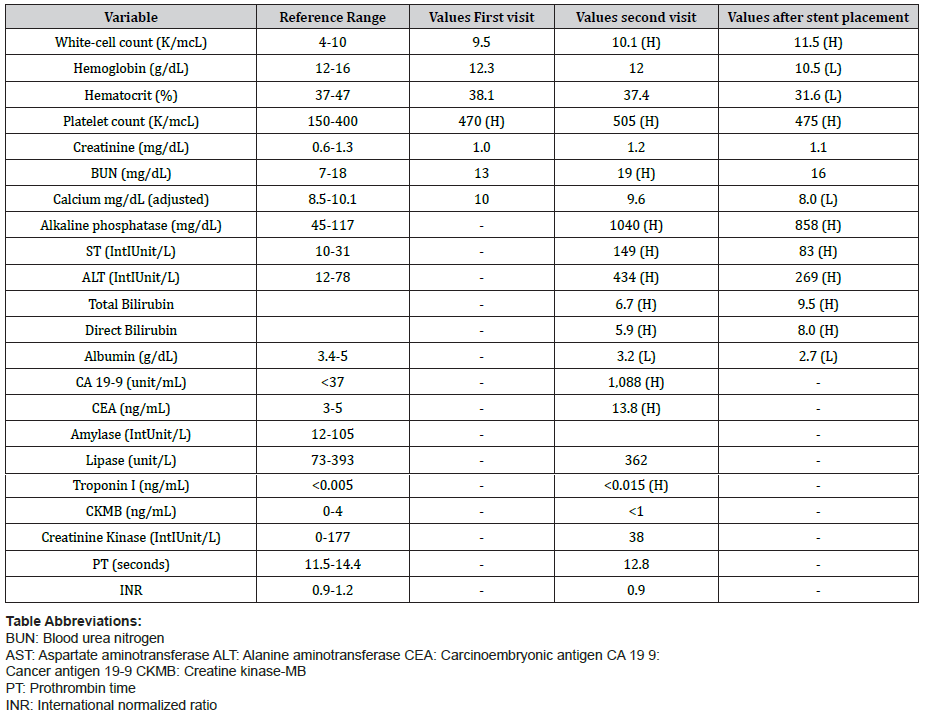

When he was informed of the findings suggestive of metastatic disease, he opted to leave without the full evaluation to identify the primary source of the malignancy, but then returned to the hospital days later for worsening symptoms. The patient was jaundiced, afebrile, and hemodynamically stable. Labs were significant for elevated alkaline phosphatase, AST, ALT, and total and direct bilirubin [Table 1].

Table 1:Blood work on first and second admissions, and after stent placement.

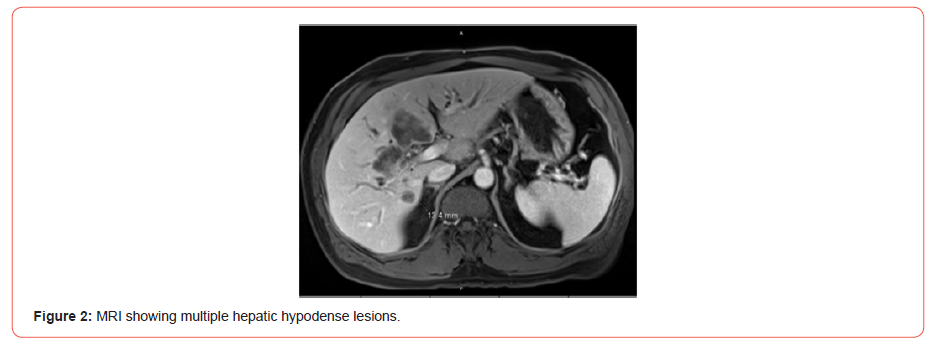

An endoscopic ultrasound and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography with biliary sphincterotomy and liver biopsy was performed, which unfortunately confirmed moderately differentiated cholangiocarcinoma. MRI showed a large infiltrative mass encasing the common hepatic and proximal common bile ducts with metastatic lesion within the right and left liver lobes. He also had metastatic nodal involvement along the periportal portacaval and retroperitoneal regions [Figure 2].

The patient was informed of his diagnosis during the hospital stay and the gastroenterologist placed a common bile duct stent. A consultation was placed with an oncologist; however, the patient preferred to follow up with an unspecified oncologist closer to home. Notes from the hospitalist suggested he was concerned the patient had an element of denial at the time of discharge. During hospitalization, he had made numerous comments in response to being told he has a malignancy, such as “I’m fine” and “I really think I’m OK.” When asked if he understood his diagnosis, he responded that he did and would indeed be seeing a specialist.

Days later, however, he returned to his PCP and stated he was not aware of the outcome of the biopsy or imaging, nor had he followed up with oncology. He endorsed itchy skin, weight loss, and poor sleep. He also noted that he changed his diet and was now drinking pureed vegetables in an effort to “cleanse his liver.” His wife was in the room with him and did not appear to understand the severity of her husband’s condition. The PCP created a safe and intimate atmosphere for the patient and his wife and asked them exactly how much they knew, how much they wanted to know, and how they would want that information conveyed. The patient responded that he wanted her to explain the biopsy and imaging results without foregoing any detail. The physician displayed the results on her computer and explained everything to him. After answering his questions, she calmly—but clearly—informed him and his wife that he had metastatic cancer.

The patient subsequently displayed a clear understanding of the severity of his condition and informed us that although he is very religious and believes in miracles, if God decides it is his time to go, then that is something he can accept. The PCP discussed the unlikelihood of a cure given how advanced his cancer already was but did not trivialize the power of hope. After the visit, the patient requested a referral to an oncologist for a visit that week. However, upon discussing the long-anticipated wait time and cost of treatment, he decided it would be best to seek further evaluation with an oncologist in Brazil, and by the end of that week he and his wife moved back to Brazil.

Discussion

The skill of giving patients bad news, as with other aspects of clinical medicine, is of great importance [1]. The quality of the provider’s communication and the patient’s initial response, such as denial or hope for a miracle, makes delivering bad news an essential skill not frequently found in the medical curriculum [6]. Denial is a basic mechanism for coping with stressful situations, especially in patients facing the challenge of cancer, as it reduces anxiety and allows them time to process the distressing information at a manageable rate [7]. However, denial may also interfere with getting treatment, for instance, leading patients to delay appointments with their oncologists, miss follow-ups, and exhibit non-compliance [8].

Healthcare providers commonly encounter patients hoping for a miracle stemming from a religious worldview and neglecting the patient’s spiritual needs leads to the patient disengaging in healthcare discussions. The way patients communicate hope for miraculous recoveries requires tailored responses by the clinician [9]. Providers who invite the patient to talk about miracles not only communicate acceptance and willingness to listen, but the patients are more likely to accept a diagnosis. A study at the University of Pennsylvania found that 66% of patients agreed that physicians who inquire about spiritual beliefs would strengthen their trust [10]. In comparison, 94% of patients for whom spirituality was meaningful wanted their doctors to address their spiritual sentiments and be sensitive to their values framework.

Since patients may be more likely to accept a diagnosis and comply with recommendations if they are informed of their condition by their previously established provider, a lack of a longitudinal relationship may increase communication complexity, leading to misunderstanding of prognosis or the purpose of care. Our patient’s hospital providers might not have had enough knowledge of his values and cultural, social, and spiritual nuances. The lack of such insight could explain why our patient denied understanding his diagnosis and its implications upon follow-up with his PCP despite being directly informed of his diagnosis in a hospital setting. The PCP was able to foster an understanding of the diagnosis and better convey the prognosis to him. Subsequently, the patient opted to seek affordable care in Brazil as opposed to not pursuing care after hospital discharge.

Despite the importance of the skill of breaking bad news in clinical practice, formal education for medical students and residents to communicate difficult information is limited [6]. Although denial may be a component in the early phases of coping, this thought process can become dysfunctional if it interferes with the patient seeking treatment [7]. The PCP with an established relationship can improve patient care through better communication. The PCP can incorporate the patient’s values into the care plan and address denial and spiritual needs leading to high-value care. Therefore, hospital providers should encourage a prompt office visit after discharge for the PCP to aid in prognostic discussions.

Acknowledgments

None.

Conflict of Interest

None.

References

- Orlander JD, Graeme Fincke B, Hermanns D, Johnson GA (2002) Medical residents' first clearly remembered experiences of giving bad news. Journal of General Internal Medicine 17(11): 825-831.

- von Blanckenburg P, Hofmann M, Rief W, Seifart U, Seifart C (2020) Assessing patients preferences for breaking Bad News according to the SPIKES-Protocol: the MABBAN scale. Patient Education and Counseling 103(8): 1623-1629.

- Minichiello TA, Ling D, Ucci DK (2007) Breaking bad news: a practical approach for the hospitalist. Journal of Hospital Medicine 2(6): 415-421.

- Ptacek JT, Ptacek JJ (2002) Patients' perceptions of receiving bad news about Cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology 19(21): 4160-4164.

- George L, Balboni T, Maciejewski P, Epstein A, Prigerson H (2019) "My doctor says the cancer is worse, but I believe in miracles"—When religious belief in miracles diminishes the impact of news of cancer progression on change in prognostic understanding. Cancer 126(4): 832-839.

- Vetto JT, Elder NC, Toffler WL, Fields SA (1999) Teaching medical students to give bad news: does formal instruction help? J Cancer Educ 14(1): 13-17.

- Rabinowitz T, Peirson R (2006) "Nothing is Wrong, Doctor": Understanding and Managing Denial in Patients with Cancer. Cancer Investigation 24(1): 68-76.

- Kreitler S (1999) Denial in Cancer Patients, Cancer Investigation 17(7): 514-534.

- Shinall MC Jr, Stahl D, Bibler TM (2018) Addressing a Patient's Hope for a Miracle. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 55(2): 535-539.

- Ehman JW, Ott BB, Short TH, Ciampa RC, Hansen-Flaschen J (1999) Do patients want physicians to inquire about their spiritual or religious beliefs if they become gravely ill? Archives of Internal Medicine 159(15): 1803-1806.

-

Kushinga Bvute, Samantha I Caballero and Alexander J Young. Breaking Bad News: Addressing Hope, Spiritual Needs, And Denial to Achieve High Value Care. Anaest & Sur Open Access J. 3(4): 2022. ASOAJ.MS.ID.000566.

-

Chronic epigastric pain, Metastatic disease, Oncology, Diagnosis, Cancer.

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.