Case Report

Case Report

Post-Traumatic Pediatric Cerebral Venous Thrombosis: A Case Report

Leila Drouzi1, Mohamed Harraki2, Aziza Bentalha1, Alae El Koraichi1, Salma Ec-Cherif Kettani1 and Larbi Ed-dafali1

1Department of anesthesiology, Children hospital of Rabat, Morocco

2Department of emergency, Children hospital of Rabat, Morocco

Leila Drouzi, Faculty of Medicine and Pharmacy of Rabat, Morrocco

Received Date:January 20, 2025; Published Date:February 03, 2025

Abstract

Post-traumatic cerebral venous thrombosis is a particularly rare form of cerebral vascular accident in children. Only a few cases have been reported in literature, contrasting with the high frequency of head injuries in pediatrics.

We report a case of a 9 years-old child, initially admitted for a head injury with clinical signs: a loss of consciousness initially lasting thirty minutes, vomiting and moderate headache.

The physical examination finds a conscious patient, GCS of 15, signs of intracranial hypertension evidenced by vomiting and headaches, without any sensory-motor deficit and without any clinically detectable seizures.

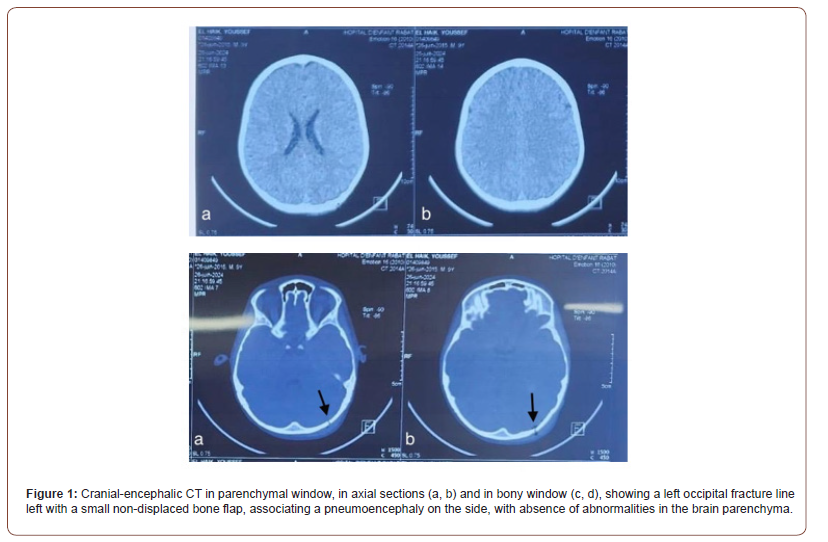

His initial brain CT scan showed a double fracture line of left occipital with a small non-displaced bone flap, associating pneumoencephaly on the side, this fracture line extends to the temporal level passing through the mastoid cells which are partially filled. Twenty-four hours later, the patient showed a slight worsening of his symptomatology.

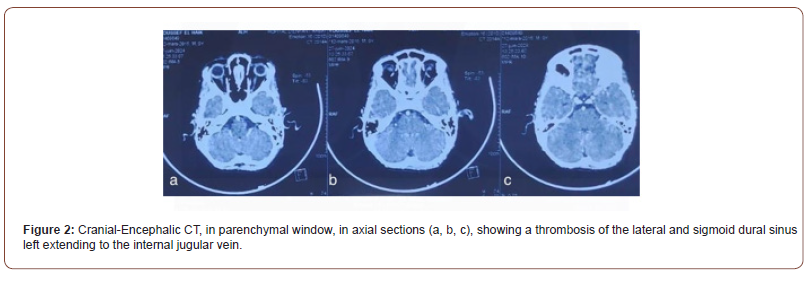

Thus, a follow-up scan was performed, revealing the presence of a thrombosis of the dural sinus left lateral and sigmoid extending to the internal jugular vein with a post-traumatic appearance.

The patient was placed on low molecular weight heparin then a switch to oral anticoagulant was made before his discharge from the department. The evolution was favorable with disappearance of the signs.

Keywords: Cerebral Venous Thrombosis; Child; Head Trauma; Anticoagulation

Introduction

Cerebral venous thromboses are rare causes of strokes in children, in addition to this is the rarity of head injuries as a source of thromboses cerebral, that is why we only find in literature only case reports of thrombosis post-traumatic cerebral venous [1,2].

The aim of our work is to describe the clinical and radiological presentations as well as the management of a post-traumatic cerebral venous thrombosis in a child revealed by a slight worsening of signs of intracranial hypertension.

Case report

We present a case of a previously healthy nine-year-old female, with no notable pathological history, who was admitted in the children’s hospital of Rabat for management of an isolated closed head trauma due to a public road accident.

The interrogation would have revealed a notion of initial loss of consciousness of thirty minutes, accompanied by moderate headache, and two episodes of vomiting.

The neurological examination at admission found a conscious patient, Glasgow Coma Scale at 15, without sensory-motor deficit, with signs of intracranial hypertension.

The patient underwent brain computed tomography at H+6 after the trauma, which revealed: a double fracture line of the left occipital with a small non-displaced bone flap, with a pneumoencephaly on the side, this fracture line extends at the temporal level passing through the mastoid cells which are partially filled. (Figure 1).

Twenty-four hours later, the patient presented a slight worsening of her symptoms (intense headaches, vomiting), without any notion of convulsions or signs of focalization.

A control CT scan was performed, showing the presence of thrombosis of the lateral dural sinus and left sigmoid dural sinus extending to the internal jugular vein (Figure 2).

A thrombophilia laboratory test was performed, returned without anomalies, the diagnosis of a post-traumatic cerebral venous thrombosis was therefore retained.

Given the stability of the traumatic lesions, a curative dose anticoagulation treatment based on low molecular weight heparin was started, then a subsequent switch to vitamin K antagonist was suggested.

The clinical evolution was deemed favourable, with disappearance of headaches and vomiting after three days of treatment without neurological sequel at distance.

Discussion

Cerebral venous thromboses are rare both in adults and children, representing thus 10% of all cerebrovascular accidents in children [3], however, post-traumatic cerebral venous thromboses represent 1.1% of cases [4], in its rarity, is added the fact that it is most often underdiagnosed, and very few cases have been described. We find in literature only case reports, or studies concerning limited series of patients.

From a physiological point of view, the manifestations of cerebral vascular thrombosis fall under two mechanisms that occur simultaneously in the majority of cases, thus involving the existence of a cerebral edema associated with softening hemorrhagic responsible of intracranial hypertension signs, and venous infarcts responsible of focal signs [5].

Most often, a predisposing factor or a triggering circumstance, namely: infection (sinusitis, otitis, mastoiditis), hereditary thrombophilia, a notion of recent surgery, the traumatic context, systemic diseases, genetic causes, hematological diseases, and therefore the etiology of cerebral venous thrombosis is divided into two main parts: infectious causes named septic thromboses, and non-infectious causes called aseptic venous thrombosis. In our case, the etiology was clearly post-traumatic after eliminating all the other causes.

Clinical manifestations are generally varied, non-specific and mainly depend on the location of the cerebral vascular thrombosis. Commonly, we find headaches, described in nearly 90% of cases, thus the onset of the latter is related to the increase in intracranial pressure. Headaches are often described as diffuse and progressive, occurring over several days. In association with headaches, the patients may develop significant papilledema, sometimes manifesting as a decrease in visual acuity. Cerebral venous thrombosis can also manifest as seizures, focal or generalized. Other clinical manifestations depend on the location of parenchymal complications of cerebral thrombosis (infarction venous or hemorrhage) notably a motor deficit, aphasia or sometimes sensory disturbances. Finally, some characteristic clinical manifestations should evoke a cerebral vascular thrombosis, which is the case of the involvement of the deep cerebral venous system that can be manifested by a coma, preceded by psychiatric disorders, associated with a bilateral motor deficit [6,7]. Cavernous sinus thrombosis is also quite typical, combining painful ophthalmoplegia and chemosis. However, the main manifestations clinically in our patient were as follows: signs of intracranial hypertension consisting of headaches and vomiting without any notion of seizures or disturbance of consciousness.

The positive diagnosis mainly relies on: the angio-MRI which remains the reference examination for both diagnosis and followup [8,9]. In our context, the brain computed tomography is the accessible imaging in emergency conditions.

The priority of therapeutic management in the acute phase mainly relies on symptomatic treatment according to the severity of the clinical manifestations, however, anticoagulants remain the reference treatment [10].

For the choice of anticoagulant, it appears in the literature that the use of low molecular weight heparin is easier. Then a switch to vitamin K antagonists or direct oral anticoagulants is strongly requested to achieve a satisfactory level of anticoagulation. But their use can problematic if cerebral venous thrombosis has been associated with intracranial haemorrhage [11].

The average duration of treatment is usually from three to six months, depending on the risk of recurrence [12].

The stability of the brain lesions in our patient allowed us the early introduction of anti- coagulation at curative doses.

The majority of patients have a complete recovery at 6 months, the mortality associated with CVT is furthermore low, estimated between 5 and 10%, due either to a direct consequence of CVT (vasogenic edema diffuse, temporal involvement) or associated with a underlying pathology, or also associated with the nonanti- coagulation [13,14]. Nevertheless, some patients develop neuropsychological sequels.

The absence of risk factors as well as early anticoagulation - thanks to the stability of the traumatic lesions - have probably allowed for a favorable evolution in our patient, with regression of clinical signs, and without neurological sequel.

Conclusion

Indeed, post-traumatic cerebral venous thrombosis remains a rare entity of vascular accident in children, but a diagnosis and an early curative anticoagulation remain the only guarantees of a favourable outcome, hence the interest in mentioning this diagnosis in the face of any worsening in clinical signs even subtle in a child who is a victim of head trauma, just like in our case.

More advanced studies must continue to better position this complication in terms of epidemiology, therapy, and prognosis.

Acknowledgement

None.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest.

References

- Ritchey Z, Hollatz AL, Weitzenkamp D, et al. (2016) Pediatric cortical vein thrombosis: frequency and association with venous infarction. Stroke 47(3): 866-868.

- Cerebral Venous Thrombosis in Children: About a Case in Bamako Kanté M, Koné I, Traoré Y, Traoré M, Samaké D, Sacko D, Kéita CO, Sylla F3

- (2021) High Authority of Health, National Protocol for Diagnosis and Care (PNDS), Venous Thrombosis in Children, Paris.

- Thrombosis of the Lateral Sinus and The Jugular Vein After A Trauma Closed Cranial.

- Lebas A, Chabrier S, Tardieu M, Kossorotoff M, Nowak-Göttl U, et al. (2011) Treatment anticoagulant treatment of cerebral venous thromboses in children and newborns, the recommendations of the French Society of Pediatric Neurology (SFNP), Archives of Pediatrics 16(3): 219-228.

- Ritchey Z, Hollatz AL, Weitzenkamp D et al. (2016) Pediatric cortical vein thrombosis: frequency and association with venous infarction. Stroke 47(3): 866-888.

- Dalila B, Djamila D B, Djilali B A, Abdenour S (2020) Cerebral Venous Thrombosis in children regarding a hospitalized series in pediatric intensive care. Global Scientific Journals.

- Agid R, Shelef I, Scott JN, Farb RI (2008) Imaging of the intracranial venous system. Neurologist 14(1): 12-22.

- Naima B, Safaa E, Ghizlane Noureddine R, Said Y, Ghizlane Draiss et al. (2019) Cerebral venous thrombosis in children regarding of a series of 12 cases. Pan African Medical Journal.

- Ferro Jm, Canhão P, Stam J, Bousser Mg, Barinagarrementeria F, ISCVT Investigators (2004) Prognosis of cerebral vein and dural sinus thrombosis: results of the International Study on Cerebral Vein and Dural Sinus Thrombosis (ISCVT). Stroke 35(3): 664-670.

- Delgado Almandoz Je, Kelly Hr, Schaefer Pw, Lev Mh, Gonzalez Rg, Romero Jm (2010) Prevalence of traumatic dural venous sinus thrombosis in high-risk acute blunt head trauma patients evaluated with multidetector CT venography. Radiology 255(2): 570-577.

- Nomazulu Dlamini, Lori Billinghurst, Fenella J Kirkham (2010) Cerebral Venous Sinus (Sinovenous) Thrombosis in Children. Neurosurg Clin N Am 21(3): 511-527.

- Sébire G, Tabarki B, Saunders, Leroy I, Liesner R, et al. (2005) Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis in children: risk factors, presentation, diagnosis and outcome. Brain 128(Pt 3): 477-489.

- Mallick AA, Sharples PM, Calvert SE, Jones RWA, leary M, et al. (2009) Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis: a case series including thrombolysis. Arch Dis Child 94(10): 790-794.

-

Leila Drouzi, Mohamed Harraki, Aziza Bentalha, Alae El Koraichi, Salma Ec-Cherif Kettani and Larbi Ed-dafali. Post-Traumatic Pediatric Cerebral Venous Thrombosis: A Case Report. Anaest & Sur Open Access J. 6(1): 2025. ASOAJ.MS.ID.000628.

-

Mater Dei Hospital, Hypertension, Diabetes Mellitus, Gastro-Oesophageal Reflux Disease, Ischaemic Heart Disease, Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease, Body Mass Index, Standard Deviation

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.