Review Article

Review Article

An update on the role of antibiotic prophylaxis for preventing burn wound infections in burn patients

Dowling, Department of Surgery, Mater Dei Hospital, Malta

Received Date:October 28, 2024; Published Date:November 04, 2024

Abstract

Background: Burns are a primary cause of morbidity and mortality in any health setting. They have a myriad of complications often resulting from the complex physiological changes they cause in the body. Burns provide an optimized medium for bacteria to grow, hence burn wound infection is a very common presentation in any Burns Unit. Infection may result in a longer stay in intensive care, longer length of hospital stays, higher need for debridement and grafting and higher mortality rates. For this reason, some units are using prophylactic antibiotics for all burn patients. However, other centers argue that routine prophylactic antibiotics increase adverse drug reactions and add lead to multi drug resistant organisms. This review will tackle these contradicting views and assess the rate of burn wound infection with or without prophylactic antibiotics.

Conclusion: The studies relating to prophylactic antibiotics in burns have inconclusive results. Different authors discuss the benefits and downsides of prophylactic antibiotics in burn patients. More studies with greater sample size are needed to be able to draw guidelines on the topic.

Keywords:Burns; Prophylactic antibiotics; Burn wound infection

Abbreviations:TBSA: Total body surface area; SAP: Systemic antibiotic prophylaxis

Introduction

Burns are a worldwide public health challenge with substantial number of infections and deaths annually [1]. They are a primary cause of mortality within any health institution along with significant physical and psychological morbidity in patients and their relatives [2]. Burn complications may be devastating and have lifelong sequelae like scarring and contractures [3]. Such injuries also have a substantial financial burden mostly associated with the complicated treatment they entail ranging from a long intensive care stay to specialized dressings, excision and grafting and extensive rehabilitation [3,4].

The local reaction to a burn comprises oedema, increased microvascular permeability namely due to the direct heat effect, vasodilation and increased extravascular osmotic activity. The change in interstitial fluid within the heat damaged tissue causes rise in hematocrit and fall in plasma volume with decreased cardiac output and hypoperfusion within the cells. If fluids are not adequately replaced, hypovolemic shock will develop [5]. A good understanding in burn pathophysiology is essential for effective fluid resuscitation however complications related to burn wound consequences still have a significant effect on morbidity and mortality rates to date [6].

Burns provide an optimized medium for bacteria to proliferate and enter the bloodstream. The epithelial barrier loss, hypermetabolic state and immunosuppression predispose to infection in burn patients [7]. The burn itself is a source of local and systemic complications as it leads to a dysfunction in the immune system, a higher bacterial load, the risk of bacterial translocation within the gastrointestinal tract, longer hospital length of stay and a variety of diagnostic and therapeutic interventions that may have devastating complications [6]. All these factors lead to a higher incidence of septic shock in burns patients [5]. Alternative sources of infection other than wound infection in burn patients include pneumonia, catheter associated infections and thrombophlebitis [8].

Improved outcomes for burn patients have been attributed to improved fluid resuscitation, better nutrition, optimum pulmonary and burn wound care and more efficient infection control guideline and practices [8]. The concept of early excision and grafting has made significant refinements in burn care. However, to this day and age, septicemia remains the major cause of death in burn patients [1,9].

The burden that infections in burn patients may create has led to some units to prescribe prophylactic antibiotics to their patients. However, prophylactic antibiotic therapy may increase adverse drug reactions and lead to multi drug resistance [7,8]. This controversy relating to prophylactic antibiotics has led to ongoing research to assess risks and benefits of such procedure. Drug resistance is an ever-increasing problem in any hospital setting [1].

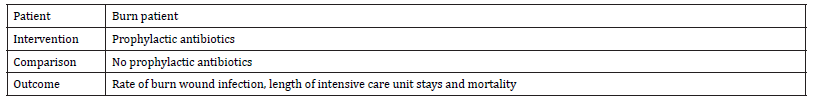

In view of this, a literature review was carried out relating to available literature about antibiotic prophylaxis in burns. The aim of this review is to analyses rates of burn wound infection rates when using prophylactic antibiotics. Secondary outcomes include assessing the length of stay in intensive care and mortality rates in these patients. The aim was set according to PICO framework as illustrated in Table 1.

Table 1:Aim of literature review as per PICO Framework.

Search Strategy: An online search was conducted on Ovid Medline and PubMed to answer the research question. Data from 2017 to 2022 in English language was considered. This five-year timeframe was chosen to obtain recent results about the topic. Studies retrieved included retrospective studies and systematic reviews. All studies were carried out after 2017 implying recent data from single or multi-center studies (Table 2).

Table 2:Search Results.

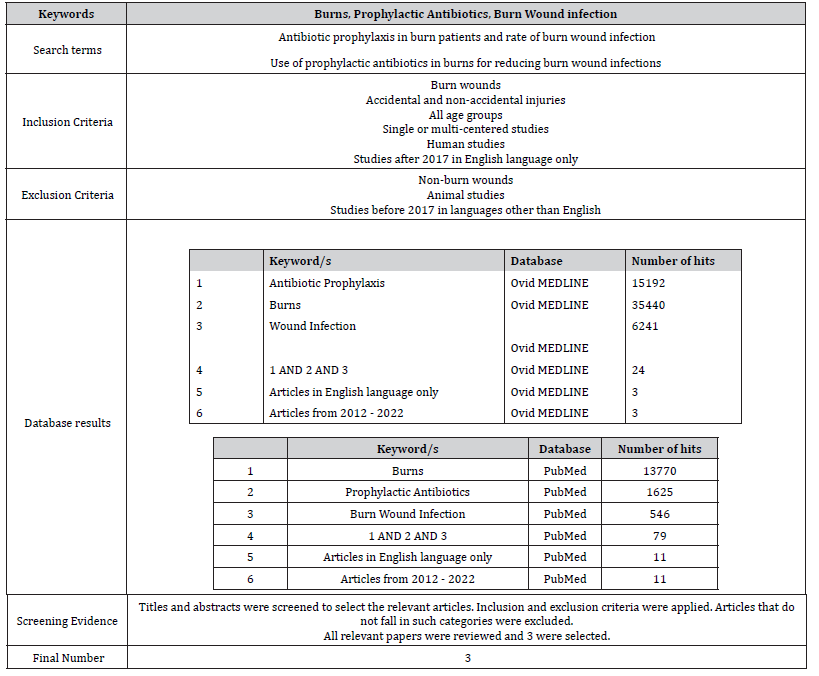

Three articles will be considered for this literature review. Selection was based on satisfying as many criteria as possible of the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Literature will be evaluated using the Critical Appraisal Skill Programmed checklist [10] and graded by the Harbour & Miller [11] hierarchy of evidence.

Literature Review

The studies considered include:

1) Systemic antimicrobial prophylaxis in burn patients:

systematic review by Ramos, et al. [7].

2) Role of systemic antibiotic prophylaxis in acute burns:

A retrospective analysis from a tertiary care center by

Muthukumar, et al. [1].

3) The Wound Microbiology and the Outcomes of the

Systemic Antibiotic Prophylaxis in a Mass Burn Casualty

Incident by, Yeong et al. [12].

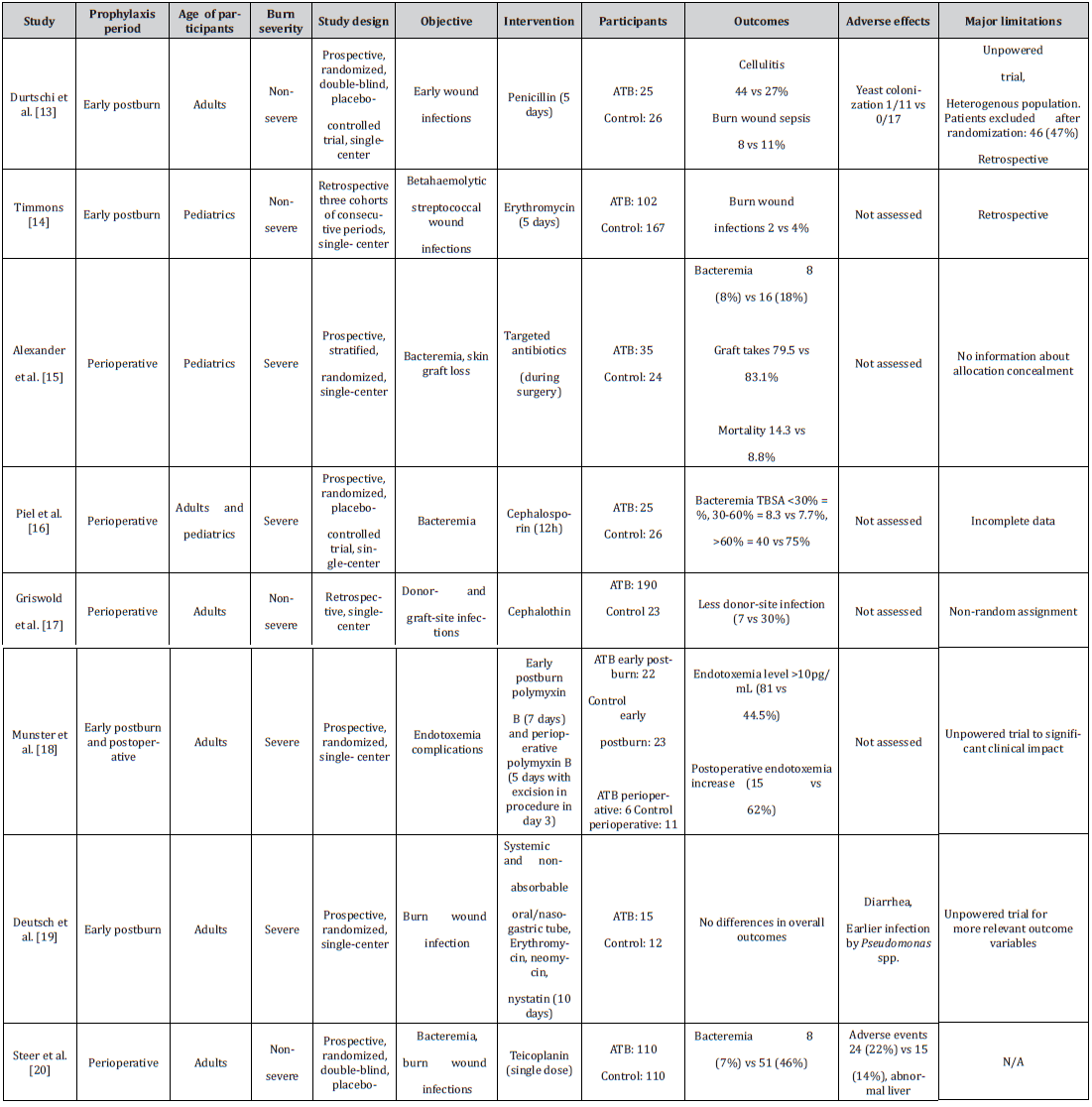

Ramos et al. [7] analyze systemic antimicrobial prophylaxis in burn patients. The main objective of this systematic review was to review studies relating to systemic antibiotics in burn patients. A key finding was that antibiotic prophylaxis might be effective in prevention of graft loss however there is poor evidence relating to use of antibiotic in graft loss (Figure 1).

Table 3 summarizes the key points of Ramos et al [7].

Table 3:Aims, method and results for Ramos et al. [7].

The objective of the study is clearly identified at the beginning and clear inclusion and exclusion are set out as indicated. A clear indication of inclusion and exclusion criteria limits confounding as much as possible. However, the authors fail to include primary and secondary outcomes that were sought from each trial and may introduce room for bias. Additionally, selection methods are not indicated at any point and this promotes selection bias.

Ramos, et al. [7] declare no conflict of interest and no funding sources in this literature review. However, individual studies do not all contain this declaration. Some also lack ethical approval. Research studies involving human studies are bound to obtain the necessary informed consent and ethical approval to achieve good research governance. Hence lack of mention of these two points implies poor research governance.

The methodology of each clinical trial is briefly indicated. Details about search strategy, sample size and power calculation, correspondence to authors and details about unpublished or incomplete data are unheard of in the literature review. These create publication bias. Moreover, lack of power calculation introduces risk of Type II error and may hinder validity of some of the studies. A good number of the studies are multicentered to encounter this problem and get a big sample size as much as possible, yet still there is no reference to any power calculation of the publications.

Ramos et al. [7] had two reviewers to select the publications that match inclusion criteria. However, there is no mention of blinding of each study to aid selection. The GRADE system was used to assess evidence with no clue of the grades of each study and the grading difference between the two reviewers. This potentially means reduced power and suggests a potential source of selection bias.

Results are very well displayed in Table 4.

Table 4:Clinical trials comparing antibiotic prophylaxis in burns vs placebo or no intervention adapted from Ramos et al. [7]). ATB=antibiotic, MV=mechanical ventilation, TBSA=total body surface area.

The results are self-explanatory yet they lack details on the calculations used and whether univariate and/or multivariate analysis were performed for each study, increasing risk of covariance. As previously mentioned, the power of the studies is indeterminable from the information presented hence one cannot assess significance of results fully.

In conclusion, data from most of the clinical trials reviewed implies that there is not enough evidence to support the role of systemic antibiotic prophylaxis in the management of burn patients. Prophylaxis may be considered in those needing mechanical ventilation and in skin grafting surgery as it may reduce rate of infection. The systematic review may be graded 1- according to Harbour & Miller [11] classification given the high risk of bias.

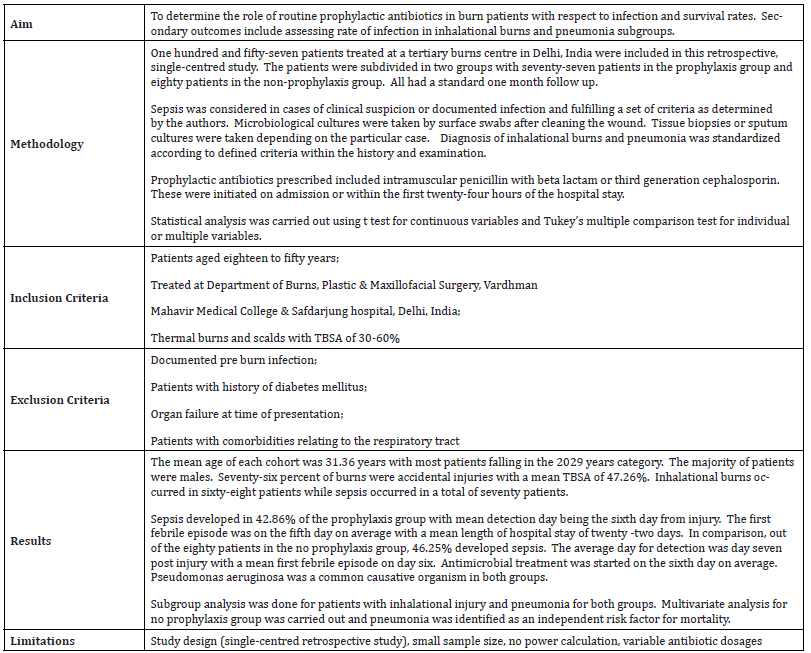

The retrospective study by Muthukumar et al. [1] relates to the role of systemic antibiotic prophylaxis in acute burns. The study analyzed data of one hundred fifty-seven patients divided in two study arms-with and without antibiotic prophylaxis. It was a single-centered study carried out at a tertiary burn care center in India over six months. The aim of the study was to assess the role of antibiotic prophylaxis with regards to infection and mortality rates.

The main conclusion of this analysis was that routine use of prophylactic antibiotics in burn patients does not affect the rate of infection and mortality. Antibiotic prophylaxis is useful in some subgroups such as in patients with inhalational burns and burn patients suffering from pneumonia.

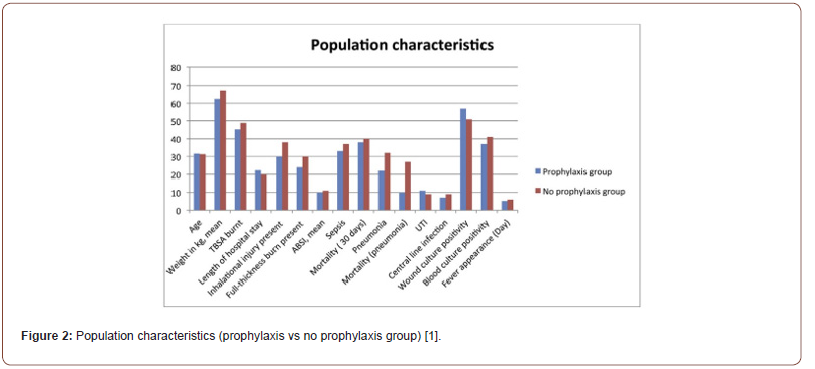

The aim, methods, results and limitations of the study are summarized in Table 5. The objective of the study is well defined with primary and secondary outcomes indicated so the study is well designed to answer the research questions. Data collection methods were also chosen to meet these outcomes. The authors define inclusion and exclusion criteria of the study so that it is easily reproducible and it has increased reliability. The selection method of patients is not indicated creating risk of selection bias. Additionally, the study lacks a power calculation increasing risk of Type II error. Patients included are from a single-center in a developing country and may not be completely relevant to the local population or to most European countries. This reduces external validity.

Table 5:Aims, method, results and limitations for Muthukumar et al. [1].

The study has a number of standardized factors namely criteria for sepsis, technique for microbiological samples, examination findings for inhalational burn diagnosis and type of antibiotics used. However, there is no mention of the level of expertise of the surgeon/nurse taking swabs for culture or the experience of the surgeon carrying out initial diagnosis of inhalational injury. Additionally, there is no indication as to whether the same surgeon follows the patient throughout the whole month. All these factors introduce risk of information bias and create a high degree of variability. These might lead to decreased sensitivity of the study.

Statistical analysis was adequately designed. The authors had particular tests for categorical and noncategorical data such as the t test being used for continuous variables. A significance level of p<0.05 was set. A combination of univariate and multivariate analysis decreases risk of covariance and increases statistical rigor. Muthukumar et al. [1] declare no conflicts of interest however fail to mention ethical approvals which reflects poor research governance as there is a higher risk of breach of Declaration of Helsinki [13].

Results are well explained with graphic representation that help the reader even more. A number of characteristics in the prophylaxis vs no prophylaxis group are identified and compared as per Figure 2 [14-21].

Results show no difference between both groups with regards to rate of sepsis and length of stay. Very minimal difference is noted in the inhalational/pneumonia prophylaxis group with marginally improved outcomes– lower rate of sepsis, decreased length of stay and decreased mortality. These results provide an answer to the research question however they are very limited with high degree of bias.

In summary the study concludes that there is no significant difference in infection rates in burns patients with or without prophylactic antimicrobial therapy. The study has high degree of bias and confounding and would be graded as 2- according to Harbour & Miller classification [11]. Larger studies from multiple centers are required to improve external validity and have solid conclusions for any recommendations or change in practice.

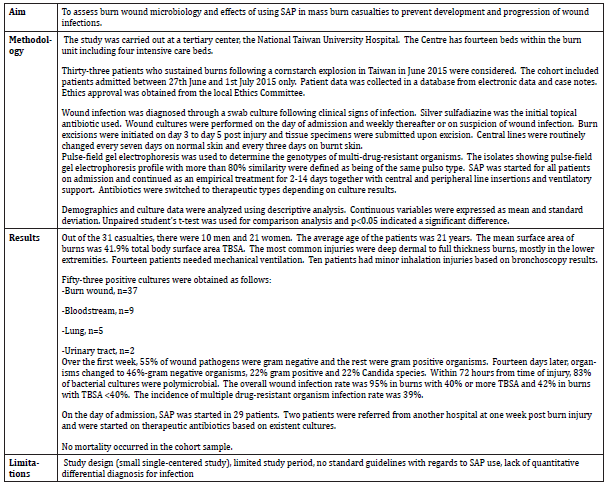

Yeong et al [12] describe the wound microbiology and the outcomes of the systemic antibiotic prophylaxis in a mass burn casualty incident. Thirty-one patients treated at a tertiary hospital in Taiwan in 2015, following a cornstarch explosion, were considered in this retrospective study. The authors analyzed the wound microbiology and effect of SAP of patients involved in this incident. They looked at wound infection rate, type of wound pathogens and rate of blood stream infections [22-30].

The main finding from the study was that the use of SAP for two to fourteen days following admission resulted in a reduction of wound infection rate from 45% at week 1 to 10% at week 4. Polymicrobial and rare pathogen wound infections were common among this cohort, namely due to sterility breech. No blood stream infections were evident at week 1 following burn injury [31].

Table 6 highlights the aims, method, results and limitations of this study [12]. The aim of this retrospective study is similar to the study’s title. Although self-explanatory, there are no primary or secondary outcomes defined and the objective is subject to the reader’s interpretation. Data is collected from a single-center for one mass burn casualty incident over one month. A power calculation was not done when choosing the sample size. Additionally, there are no inclusion or exclusion criteria and the selection criteria are not identified. These limited parameters reduce external validity and increase chance of bias with a higher potential for Type II error.

Table 6:Aims, method, results and limitations for Yeong et al. [12].

Standard techniques were used to obtain diagnosis through swab cultures upon signs of clinical infection, an initial silver sulfadiazine cream and repeated cultures. Lines were routinely changed to minimize risk of infection. Nonetheless the level of expertise of the doctor caring for all casualties, whether all patients were under the care of same physician and techniques used to insert lines and catheters are not mentioned. These factors introduce risk of observer bias.

Statistical analysis is very limited. The unpaired t-test was used to analyze continuous variables and a statistically significant level was set at 0.05. There is no univariate or multivariate analysis hence one cannot ascertain whether results are due to significance or covariance. This implies poor statistical rigor [32].

The main outcome of the study indicated the commonest pathogens in burn wounds, with Staphylococcus species and Enterococcus faecalis being the commonest organisms cultured in the first week while multiple drug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii was the commonest pathogen cultured thereafter. A delay to first blood stream infection was noted. Results were compared to a similar study by Sherry et al. [33] stating that microbiology of wildfire burn victims differs significantly from other burns mainly due to the difficult preventative measures in a burn disaster. SAP prevented transmission of rare human pathogens and the rate of infection overall and delayed the first episodes of blood stream infections. High incidence of fungal and multiple drug-resistant organisms was noted in SAP strategies.

In conclusion, the study implies that SAP is beneficial in burn wounds. However, results are limited to mass burn casualty incidents and applicable on a very small population. Given the high risk of bias, the study may be graded as 2- according to Harbour & Miller classification [11]. Further studies with greater numbers over more centers are required to obtain transferable results.

Conclusion

All studies relating to prophylactic antibiotics in burns analyzed in this review have inconclusive results [1,7,12]. Ramos et al. [7] described no benefit in systemic antibiotic prophylaxis. This is also supported by Muthukumar et al. [1]. Contrastingly, Yeong et al. [12] suggested that systemic antibiotic prophylaxis is beneficial in burns. However, it must be noted that this study was carried out following a mass burn casualty incident. All authors were aware and exhibit the limitations of their studies namely single centered studies with lack of power calculation and non-standardized data collection techniques.

The studies have a score of 1- or 2- on Harbour & Miller [11] classification given the high degree of bias. This urges for more rigorously conducted studies, ideally from multiple centers with greater numbers.

Acknowledgment

None.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest.

References

- Muthukumar V, Arumugam PK, Bamal R (2020) Role of systemic antibiotic prophylaxis in acute burns: A retrospective analysis from a tertiary care center. Burns: journal of the International Society for Burn Injuries 46(5): 1060-1065.

- Temiz A, Ayşe Albayrak, Rıfat Peksöz, Esra Dışcı, Ercan Korkut, et al. (2020) Factors affecting the mortality at patients with burns: Single center results. Turkish 26(5): 777-783.

- Ashouri S (2022) An Introduction to Burns. Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation clinics of North America 33(4): 871-883.

- Ozlu B, Basaran A (2022) Infections in Patients with Major Burns: A Retrospective Study of a Burn Intensive Care Unit. Journal of Burn Care & Research 43(4): 926-930.

- Arturson G (1980) Pathophysiology of the burn wound. Ann Chir Gynaecol 69(5): 178-190.

- Sharma BR (2007) Infection in patients with severe burns: causes and prevention thereof. Infectious disease clinics of North America 21(3): 745-759.

- Ramos G, Cornistein W, Torres Cerino G, Nacif G (2017) Systemic antimicrobial prophylaxis in burn patients: systematic review. Journal of Hospital Infection 97(2): 105-114.

- Church D, Elsayed S, Reid O, Winston B, Lindsay R (2006) Burn wound infections. Clinical Microbiology Reviews 19(2): 403 -434.

- Millan LS, et al. (2012) Bloodstream infection by multidrug-resistant bacteria in patients in an intensive care unit for treatment of burns: a 4-year experience. Revista Brasileira de Cirurgia Plástica 27(3): 374-378.

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) (2013) CASP Checklist (Online). Oxford.

- Harbour R, Miller J (2001) A new system for grading recommendations in evidence-based guidelines. British Medical Journal 323(7308): 334-336.

- Yeong E, Wang-Huei Sheng, Po-Ren Hsueh, Szu-Min Hsieh, Hui-Fu Huang, et al. (2020) The Wound Microbiology and the Outcomes of the Systemic Antibiotic Prophylaxis in a Mass Burn Casualty Incident. Journal of Burn Care & Research 41(1): 95-103.

- World Medical Association (2013) World Medical Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA 310(20): 2191-2194.

- Durtschi M, Orgain C, Counts G, Heimbach D (1982) A prospective study of prophylaxis penicillin in acutely burned hospitalized patients. The Journal of Trauma 22(1): 11-4.

- Timmons M (1983) Are systematic prophylactic antibiotics necessary for burns?. The Annals of the Royal College of Surgeons of England 65(80-82).

- Alexander J, Macmillan B, Law E, Kern R (1984) Lack of beneficial effects of restricted prophylactic antibiotics for debridement and/or grafting of seriously burned patients. Bulletin and Clinical Review of Burn Injuries 1: 20.

- Piel P, Scarnati S, Goldfarb IW, Slater H (1985) Antibiotic prophylaxis in patients undergoing burn wound excision. The Journal of Burn Care & Rehabilitation 6(5): 422-424.

- Griswold J, Grube B, Engrav L, Marvin J, Heimbach D (1989) Determinants of donor site infections in small burn grafts. The Journal of Burn Care & Rehabilitation 10(6): 531-535.

- Munster A, Xiao G, Guo Y, Wong L, Winchurch R (1989) Control of endotoxemia in burn patients by use of polymyxin B. The Journal of Burn Care & Rehabilitation 10(4): 327-330.

- Deutsch D, Miller S, Finley R (1990) The use of intestinal antibiotics to delay or prevent infections in patients with burns. The Journal of Burn Care & Rehabilitation 11(5): 436-442.

- Steer J, R P Papini, A P Wilson, D A McGrouther, L S Nakhla, et al. (1997) Randomized placebo-controlled trial of teicoplanin in the antibiotic prophylaxis of infection following manipulation of burn wounds. British Journal of Surgery 84(6): 848-853.

- Rodgers G, Fisher M, Lo O, Creswell A, Long S (1997) Study of antibiotic prophylaxis during burn wound debridement in children. The Journal of Burn Care & Rehabilitation 18(4): 342-346.

- Kimura A, T Mochizuki, K Nishizawa, K Mashiko, Y Yamamoto, et al. (1988) Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole for the prevention of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus pneumonia in severely burned patients. Journal of Trauma 45(2): 383-387.

- Sheridan R, Weber J, Pasternack M, Tompkins R (2001) Antibiotic pro-phylaxis for group A streptococcal burn wound infection is not necessary. The Journal of Trauma 51(2): 352-355.

- Ergün O, Celik A, Ergün G, Ozok G (2004) Prophylactic antibiotic use in pediatric burn units. European Journal of Pediatric Surgery 14: 422-426.

- Ugburo A, Atoyebi O, Oyeneyin J, Sowemimo G (2004) An evaluation of the role of systemic antibiotic prophylaxis in the control of burn wound infection at the Lagos University Teaching Hosptial. Burns 30(1): 43-48.

- De La Cal M, Enrique Cerdá, Paloma García-Hierro, Hendrick K F van Saene, Dulce Gómez-Santos, et al. (2005) Survival benefit in critically ill burned patients receiving selective decontamination of the digestive tract: a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind trial. Annals of Surgery 241(3): 424-430.

- Lyons J, Christopher Davis, Mary T Rieman, Robert Kopcha, Ho Phan, et al., (2006) Prophylactic intraveneous immune globulin and polymyxin B decrease the incidence of episodes and hospital length of stay in severely burned children. Journal of Burn Care & Research 27(6): 813-818.

- Ramos G, Marcela Resta, Enrique Machare Delgado, Ricardo Durlach, Liliana Fernandez Canigia, et al. (2008) Systemic perioperative antibiotic prophylaxis may improve skin autograft survival in patients with acute burns. Journal of Burn Care & Research 29(6): 917-923.

- Chahed J, et al. (2014) Burns injury in children: is antibiotic prophylaxis recommended?. African Journal of Paediatric Surgery 11(4): 323-325.

- Mulgrew S, Khoo A, Cartwright R, Reynolds N (2014) Morbidity in pediatric burns, toxic shock syndrome, and antibiotic prophylaxis: a retrospective comparative study. Annals of Plastic Surgery 72(1): 34-37.

- Tagami T, Matsui H, Fushimi K, Yasunaga H (2016) Prophylactic antibiotics may improve outcome in patients with severe burns requiring mechanical ventilation: propensity score analysis of Japanese nationwide database. Clinical Infectious Diseases: an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America 62(1): 60-66.

- Sherry N L, Padiglione A A, Spelman W, Cleland H (2013) Microbiology of wildfire victims differs significantly from routine burns patients: data from an Australian wildfire disaster. Burns 39(2): 331-334.

-

Jessica Dowling*. An update on the role of antibiotic prophylaxis for preventing burn wound infections in burn patients. Anaest & Sur Open Access J. 5(4): 2024. ASOAJ.MS.ID.000617.

-

Burns; Prophylactic antibiotics; Burn wound infection, Total body surface area, Systemic antibiotic prophylaxis, psychological morbidity, Rehabilitation, Immunosuppression, Gastrointestinal tract

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.