Research Article

Research Article

Determinant of, and Factors Influencing Medication Poor Adherence to Pulmonary Tuberculosis Treatment at The Tuberculosis Clinic of Mettu Karl Referral Hospital, Southwestern, Ethiopia: A Prospective Cross Sectional Study, 2021

Gudisa Bereda1*, and Gemechis Bereda

1SWAN diagnostic pharmaceutical importer, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

Gudisa Bereda, SWAN diagnostic pharmaceutical importer, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

Received Date: June 18, 2021; Published Date: July 26, 2021

Abstract

Background: Tuberculosis is an infectious bacterial disease caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis, which most commonly affects the lungs. Overall, a relatively small proportion (5-15%) of the estimated 2-3 billion people infected with myco bacterium tuberculosis will develop TB disease during their lifetime. Nonadherence to TB treatment has remained a major challenge in Ethiopia.

Objective: To discover determinant of and factors influencing medication poor adherence to pulmonary tuberculosis treatment in TB clinic of Mettu Karl Referral Hospital.

Methods: An Institutional based prospective cross-sectional study design was carried out from April 02/2021 to June 07/2021. Data was collected through employing check list and semi-structured questioner, and then the collected data was cleared, coded, and analyzed by Statistical Packages for Social Sciences 25.0 version statistical software. Variables at P-value < 0.05 in multivariate logistic regression model were considered statistically significant.

Results: The study included 168 TB patients with a response rate of 100%; 86 (51.2%) were females. The overall prevalence of medication poor adherence to pulmonary tuberculosis treatment was 27.4%. Age≥45 years(AOR:2.79;95%CI:2.451-5.337; P=0. 007),rural resident(AOR:2.79;95%CI:2.451-5.337;P=0.004),distance-from health facil ity >5 km(AOR:1.78;95%CI:1.503-2.145;P=0.001),experience of side effects (AO R:2.43;95%CI:1.970-3.153;P=0.017),HIV status negative (AOR:2.95; 95%CI: 2.610- 5.173;P=0.001),and uneducated (AOR:2.74;95%CI:2.430-4.201;P=0.008) were significantly associated with ani-tuberculosis treatment poor adherence.

Conclusion: The prevalence of medication poor adherence to pulmonary tuberculosis treatment was high. Regarding the reason for missing anti-TB medication majority were forgetfulness followed by vomiting and diarrhea and cost of transport.

Keywords: Tuberculosis; Poor Adherence; Associated Factors; TB Clinic; Mettu Karl Referral Hospital; Ethiopia

Abbreviations: TB: Tuberculosis, DOT: Directly Observed Treatment, HBCs: High Burden Countries, HIV/AIDS: Human Immune Virus/Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, MDR-TB: Multi Drug-Resistant Tuberculosis, SSA: Sub-Saharan Africa, XDR-TB: Extensively Drug Resistance tuberculosis

Introduction

Tuberculosis remains a major public health problem globally despite the fact that the causative organism has been known for more than 100 years, and highly effective drugs and vaccines have been available for decades [1]. Most people who had TB disease can be cured with early diagnosis and correct treatment. Despite this, it has been continued as a leading cause of death from a single infectious agent ranking on top of HIV/AIDS for the past five years [2]. Globally there were estimated 10.4 million new TB cases, and 600,000 new cases with resistance to rifampicin, 490,000 had multi drug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB) cases and 1.7 million people died from TB [3]. Tuberculosis (TB) is a communicable disease caused by the bacillus Mycobacterium tuberculosis. It usually affects the lungs (pulmonary TB) and transmitted when people who are sick with pulmonary TB expel bacteria into the air but can also affect other sites (extra-pulmonary TB) [4]. Complete cure requires 6 months of treatment without interruption with multiple drugs which is challenging for patients and health care workers. Incomplete TB treatment may cause prolonged TB transmission, increased risk of development of drug resistant TB, and higher mortality. TB treatment requires a prolonged and combined course of antibiotics for 2 months of intensive followed by 4 months continuation phase [5]. In the treatment of patients with MDRTB, an intensive phase of at least 8 months and a total treatment duration of at least 24 months is recommended [6]. The year2019 WHO report shows in 2018, there were about half a million new cases of rifampicin-resistant TB (of which 78% had multi drugresistant TB (MDR-TB, and many cases are developing Extensively Drug resistance (XDR) TB among re-treatment cases throughout the world. Drug-resistant (DR- TB emerges at least in part due to inappropriate treatment or sub optimal adherence to the treatment regimen [7]. Thus, poor adherence to a prescribed treatment increases the risks of morbidity, mortality, and drug resistance [8]. Many TB patients do not complete their 6-month course of anti- TB medications and are not aware of the importance of sputum re-examinations, thereby putting themselves at risk of developing multi drug-resistant and extensively drug-resistant forms of tuberculosis and relapse [9]. Non-adherence to TB treatment threatens the success of treatment, increases the risk of TB spread, causes drug resistance, and increases morbidity and mortality [10]. There is an unfavorable magnitude of poor adherence to treatment of chronic diseases including TB in the world [11]. However, greater than 90% of patients with TB are expected to adhere the treatment in order to facilitate cure. Poor adherence to treatment results failure of cure which increases the risk of development of drug resistant strains, spread of TB in the community and this in turn increases morbidity and mortality [12]. In developing countries, particularly, there are many factors affecting adherence to TB treatment as evidenced from a variety of literature’s .Age, lack of treatment support from family, extreme illness, far distance, lack of access to formal health services, traditional beliefs leading to self-treatment, low income, lack of social support, drug side effects, pill burden, lack of food, stigma with lack of disclosure, and lack of adequate communication with health professionals were some of the documented factors[13].

The disease at global level is still out of reach, and massive resource investment is still required. TB is a poverty-related disease which disproportionately affects the poorest, the most vulnerable and marginalized population groups wherever it occurs. Improving access to diagnosis and care, the basic requirements in the fight against TB, are particularly challenging in these persons [14]. Tuberculosis has been recognized as a major public health problem for more than five decades in Ethiopia. Ethiopia is one of the 22 high burden countries (HBCs), and TB remains one of the leading causes of mortality. According to the 2014 WHO report, the prevalence and incidence of all forms of TB are 211 and 224 per 100,000 of the population, respectively [15]. The WHO, in its global plan to stop TB, reports that poor treatment has resulted in the evolution of Mycobacterium tuberculosis strains that do not respond to treatment with the standard first-line combination of anti-TB medicines, resulting in the emergence of multi drugresistant TB in almost every country of the world [16]. One of the greatest dilemmas and challenges facing most TB programs is a patient that does not complete TB treatment for one reason or another, Poor adherence to treatment of chronic diseases including TB is a worldwide problem of striking magnitude [17]. To improve TB treatment outcomes, it requires a better understanding of factors that influence TB treatment non-adherence. Studies conducted in different parts of Ethiopia revealed several factors associated with anti-TB treatment non-adherence, including factors related to the health system, patient, and socio-economic characteristics [18]. As TB treatment non-adherence is an “unavoidable by-product of collisions between the clinical world and the other competing worlds of work, play, friendships and family life “the factors affecting it can be changed over time [19]. In Ethiopia, different studies have been conducted to determine the prevalence and determinants of non-adherence to TB medications [20]. Those studies reported that the prevalence of non-adherence among TB patients ranging from 8.4% to 55.8%. This is higher than the WHO recommendation of less than 10% [21]. According to recent estimates, Ethiopia stands 7th in the list of high TB burden countries. In Ethiopia, TB is the leading cause of morbidity, the third cause of hospital admissions, and the second cause of death. The estimated TB incidence of Ethiopia was 261/100,000 inhabitants in 2011. Nonadherence to anti-TB treatment may result in the emergence of multi drugresistant TB (MDR-TB), prolonged infectiousness, and poor TB treatment outcomes [22]. In sub-Saharan Africa, there is a high rate of loss to follow up of TB patients that ranged from 11.3% to 29.6%, Ethiopia is one of the seven countries that reported lower rates of treatment success (84%) [23]. In view of the need to accelerate efforts and reach the international targets set in the context of TB infection, the result of this study plays significant role by increasing awareness toward early detection and prevention of the diseases.

Methods

Study design, setting and period

An Institutional based prospective cross sectional study design was used. The study was conducted in MKRH, Mettu town, Southwest Oromia, Ethiopia which is found at 600 km from Addis Ababa. There are different wards and clinics within MKRH; those include internal medicine ward, surgery ward, pediatric ward, gynecology, and obstetrics ward, Ante natal clinic, dental clinics, tuberculosis clinic, anti-retroviral therapy clinic and ophthalmologic clinic. The study was conducted from April 02 /2021 to June 07/2021.

Study participants

All TB patients who were on anti TB treatment during the study period was source population. Duration of taking anti-tuberculosis drugs of at least one month, Drug- susceptible TB patients who were adults older than 18 years were included in the study. Those who did not agree to participate in this study, PTB patients with other diseases, such as diabetes, autoimmune deficiency syndrome (AIDS), malignant tumors and serious heart, brain, liver and kidney diseases, severely ill patient, patients with severe coughing, new patients who had not registered at TB clinic or registration at TB clinic after one month of treatment at the time of interview were excluded.

Sample size determination & sampling technique

The sample size was determined by using the Single Population proportion Formula: The sample size was determined based on ”P” value which was taken from, Southern Ethiopia, P=0.247,or 24.7% ,P=0.378,or 37.8%.n=((Za/2)2 P(1-P))/d2, n= sample size, P=prevalence of Anti-TB medication poor adherence, d=margin of sampling error tolerated, z=the standard normal value at confidence interval of 95%. n = (1.96)2(1- 0.247) x (0.247) / (0.05) 2=286. Since the total number of TB patients were less than 10,000, reduction formula (Correction Formula) will be applied as follow; nf = n/ (1+(n/N)), nf =286/ (1+(286/329) =153. When 10% contingency is added to minimize nonresponse rate. then final sample size was found to be 168. Purposive sampling technique was used to recruit samples for the study in each day of the data collection process until the desired sample size was obtained.

Data Collection Instrument and Procedures

Data was collected using an interviewer-administered questionnaire. The questionnaire was d included Socio demographic factors (age, sex, educational status, monthly income, marital status, family size, cigarette smoking, alcohol consumption, lack of family member support, effect of traditional medicine etc. Patient-Related Factors(a lack of knowledge of PTB treatment, poor self-management capability, poor self-regulation capability and misperception of health condition).medical history (number of doses taken in the month before the study interview, Side Effects history of previous anti-TB treatment and history of opportunistic infection),Medication- Related Factors (Side Effects), Health Service-Related Factors(Poor Treatment Skills of Doctors in Primary Hospitals, Lack of DOT), health provider (counseling about the expected adverse effect),and health system (time to reach a health facility, waiting time and mode of transportation). Questions pertaining to the patient-related dimension included how the patients felt about the effectiveness and importance of his/her anti-TB drugs, whether the patients felt stigmatized by the epilepsy, whether the patients had altered drug-taking behavior due to fear of addiction to the anti-TB and whether the patients changed the dosing regimen to see if their seizures recurred. The Validated 8-item Morisky Medication Adherence Scale (MMAS-8), a self-reporting tool was used to assess the patient’s adherence level to anti-TB therapy. There were 8 questions evaluating the patient’s forgetfulness, patient’s understanding of the need for continued therapy and whether the patient felt it was inconvenient adhering to a daily medication treatment plan. For questions 1, 2, 3, 4, 6 and 7, a score of zero was given for a positive response whereas a score of one was given for a negative response (Yes=0; No=1). Conversely, for item 5, a score of zero was given for a negative response whereas a score of one was given for a positive response (Yes =1; No=0). For item 8, a score of one was given for ‘Never/Rarely’ whereas a score of zero was given for ‘Once in a while/ ‘Sometimes/ ‘Usually/ All the time. The total score of MMAS-8 was 8. A Higher score indicated a higher level of self-reported adherence. Adherence level was categorized as high (Score: 8), medium (Score: 6 or 7) and low (Score:< 6). Patients who had a MMAS-8 score of 8 were considered to have a good adherence level while patients who had a MMAS-8 score of less than 8 were considered as having a poor adherence level.

Data quality Assurance

The data was screened for inconsistencies, missing values, and checked for completeness before data entry. Moreover, data quality also ensured during collection, entry & analysis.

Data processing and analysis

Data collected was analyzed by using Statistical Package for Social Science version 25.0. Categorical variables were expressed by percentage and frequency, whereas continuous variables were present by mean and standard deviation. Uni variate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were conducted to determine associated risk factors of non-adherence. The variables with p-value≤0.25 were included in the multivariable logistic regression model. The ordinal logistic regression model was used to identify risk factors for TB treatment non-adherence. The final association was prepared using multivariate logistic regression. P-value < 0.05 was considered significant.

Ethical clearance

Ethical clearance was obtained from SWAN diagnostic pharmaceutical importer. Written informed consent was obtained from each study participants after explaining the purpose and objective of the study. Patients who were not willing to participate in the study were not forced to participate. Information gathered from respondents was treated confidentially, and the norm of the community was considered and respected in the process of data collection.

Operational definitions

Good Adherence: If MMAS-8 score > 7.

Poor adherence: If MMAS-8 score < 6.

Results

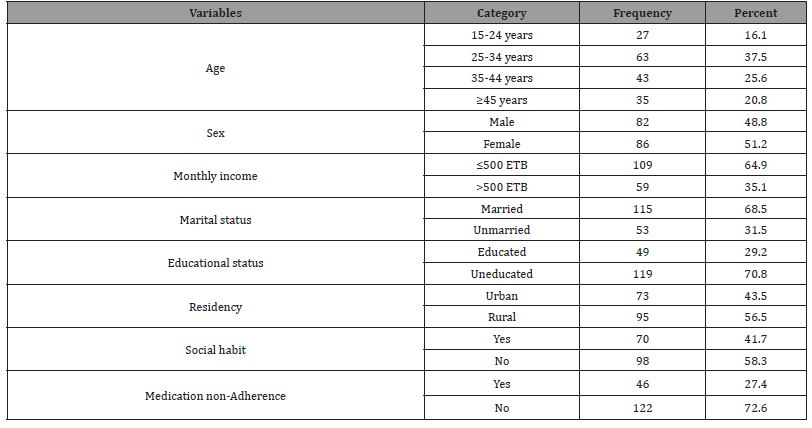

Socio-demographic and socio economic characteristic of TB patients

A total of 168 TB clients participated in the study with a response rate of 100%. The age of majority 63(375%) were between 25-34 years. Slightly above than half 86 (51.2%) were females and 115(68.5%) of participants were married. A majority 109 (64.9%) of participants were earn monthly income ≤500 ETB and 119(70.8%) respondents were uneducated. A majority 95(56.5%) of the respondents were live in the rural area and only 70(41.7%) of respondents had at least one social habit. The prevalence of medication poor adherence to pulmonary tuberculosis treatment was 46 (274%) (Table 1).

Table 1: Socio-demographic and socio economic characteristic of TB patients among TB clinic follow up, MKRH, Southwestern, Ethiopia, 2021 (n=168).

Healthcare system related characteristics of the TB patients

Regarding healthcare system related characteristics of the respondents, a majority 73 (43.5%) of patients preferable time for TB clinic were 8:00-11:00 AM and 94(56.0%) of the participants were waiting time at health facility 1-2 hr,92(54.8%) of the participants were distance to health facility >5 km,114(67.9%) of the participants were transportation cost >5 birr. A majority 70(41.7%) of the participants were being supervised by family member,66(39.3%) of the respondents were have relationship with health worker friendly. Slightly less than 80(47.6%) of the respondents have some knowledge on symptoms of TB and 83(49.4%) of the participants were stop TB medication when feeling better (Table 2).

Table 2: Healthcare system related characteristics of TB patients among TB clinic follow up, MKRH, Southwestern, Ethiopia, 2021 (n=168).

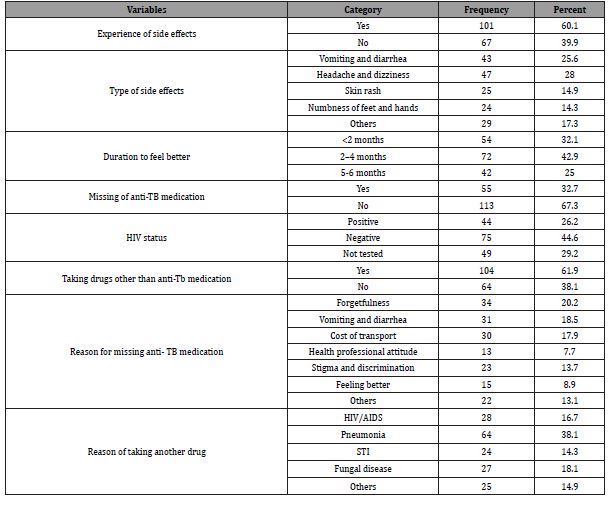

Disease and medicine related factors of TB patients

A majority 101(60.1%) of the pregnant women have experience of side effects and 47(28.0%) were have headache and dizziness type ani-TB medication side effects. A majority 72(42.9%) of the participants duration to feel better were between 2-4 months, and 55(32.7%) of the respondents were missing of anti-TB medication. Less than one third 44(26.2%) of the participants were tested HIV/AIDS positive and majority 104(61.9%) of the respondents were taking drugs other than anti-Tb medication. Regarding the reason for missing anti-TB medication majority 34(20.2%) were forgetfulness followed by 31(18.5%0 were vomiting and diarrhea and 30(17.9%) cost of transport and the reason of taking another drug were mostly due to 64(38.1%) (Table 3).

Table 3: Disease and medicine related factors of TB patients among TB clinic follow up, MKRH, Southwestern, Ethiopia, 2021 (n=168).

Factors associated with non-adherence to anti-TB therapy

The participants age ≥45 years were 2.76 times more likely cause TB medication non-adherance(AOR:2.79;95%CI:2.451- 5.337;P=0.007),and rural residency were 2. 79 times more likely cause TB medication non-adherance(AOR:2.79;95%CI:2.451- 5.337;P=0.004).Distance from health facility >5 km were 1.78 times more likely cause TB medication nonadherance( AOR:1.78;95%CI:1.503-2.145;P=0.001),and ex perience of side effects were 2.43 times more likely cause TB medication non- adherance(AOR:2.43;95%CI:1.970-3.153;P=0.017).HIV status negative(AOR:2.95; 95%CI:2.610-5.173;P=0.001) and uneducated were 2.74 times more likely cause TB medication nonadherance( AOR:2.74; 95%CI:2.430- 4.201; P=0.008). medication non-adherance(AOR:2.74; 95%CI:2.430- 4.201; P=0.008) (Table 4).

Table 4: Factors associated with non-adherence to anti-TB therapy of TB patients among TB clinic follow up, MKRH, Southwestern, Ethiopia, 2021 (n=168).

Discussion

For TB treatment to be effective, it is crucial to initiate patients on the correct treatment regimen in a timely manner (within 2 days of diagnosis) and to sustain such treatment for the correct period of time. However, TB treatment is an arduous undertaking for patients. Standard TB treatment requires the regular use of complex combined drugs for 6 to 8 months or longer [24].

The current survey revealed that the prevalence of medication poor adherence to pulmonary tuberculosis treatment was 46(27.4%) were higher than the study done in higher the study conducted in Southeast Nigeria 24.2%, Mbarara Hospital, Uganda 25%, Southwest Ethiopia 20.8% [25-27]. The difference was due to sub optimal health literacy and lack of involvement in the treatment decision- making process and prescription of complex drug regimen. Our survey was in line with Southern Ethiopia 30% [28]. Because in Ethiopia DOTS were not work properly due to lack of health care workers in the hospitals and the ministry of health were also not establish new strategy on how anti-TB medication given to the patients. Our study was higher than conducted in Ayder Referral Hospital, 55.8%, China 33.74% [29,30]. The difference was study period and sample size mean our study time period was 3 months and less sample size.

Our study revealed that regarding the reason for missing anti- TB medication majority 34(20.2%) were forgetfulness followed by 31(18.5%0 were vomiting and diarrhea and 30(17.9%) cost of transport were in line with the survey done at Gondar town health centers, Northwest [31] Ethiopia showed that forgetting, being busy with other work, and being out of home/town were the major reasons for most participants for interruption of taking anti-TB medications. The similarity was due to majority patients receiving anti-TB were due to fear of side effects they interrupt follow up and no more awareness brought to them.

In our study the participants age ≥45 years were 2.76 times more likely cause TB medication non-adherence (AOR:2.79;95%CI:2.451- 5.337;P=0.007) than age category was similar with the study conducted in Indonesia [32] which revealed the association between age and non-adherence during TB treatment has been investigated in other studies, with different results. Because the problems of decreased body size, altered body composition (more fat, less water), and decreased liver and kidney function cause many drugs to accumulate in older people’s bodies at dangerously higher levels and for long times than the younger people.

The present study showed that regarding healthcare system related characteristics of the respondents, a majority 73(43.5%) of patients preferable time for TB clinic were 8:00-11:00 AM and 94(56.0%) of the participants were waiting time at health facility 1-2 hr,92(54.8%) of the participants were distance to health facility >5 km,114(67.9%) of the participants were transportation cost >5 birr were consistent with the study conducted in Southern Ethiopia [33] revealed that nonadherence was high if the patients experienced side effects, were far from the health facility, and experienced prolonged waiting time to get medical services. The similarity was due to patients who came from the far apart especially during summer were more non-adherent due to transportation cost and weather condition.

In our study, distance from health facility >5 km was 1.78 times more likely cause TB medication non-adherence (AOR:1.78; 95%CI:1.503-2.145;P=0.001) were in line with the study conducted in southern Ethiopia [33] revealed anti-TB nonadherence among TB patients is distance to the health facility. While only 8.4% of TB patients 0-5 kms away from health facility did not adhere to anti- TB drugs, 87.5% of TB patients greater than 5 kms away from the health facility did not adhere.

The present study showed experience of side effects were 2.43 times more likely cause TB medication non-adherance (AOR:2.43; 95%CI:1.970-3.153;P=0.017) were less than the study carried out in Tigray, Northern Ethiopia [34], where the probability of adhering to anti-TB drugs among TB patients without drugs side effects was 3 times higher than in those with drugs side effects. Because the interrupt the mediation if they feel some of the medication adverse events.

In our study rural residency were 2.79 times more likely cause TB medication non- adherance (AOR:2.79;95%CI:2.451- 5.337;P=0.004) were consistent with the study done in Indonesia [32] rural residence is an independent risk factor for poor adherence. Rural residents had lack of knowledge about TB in general and treatment regimen and length in particular, loss of employment or the opportunity to work and subsequent financial difficulties, transport problem lack of access health service and medication side effects.

The current survey revealed that HIV status negative (AOR:2.95;95%CI:2.610-5.173; P=0.001) and uneducated were 2.74 times more likely cause TB medication non- adherance (AOR:2.74; 95%CI:2.430-4.201;P=0.008).

CI:2.430-4.201;P=0.008).

Conclusion

The prevalence of medication poor adherence to pulmonary tuberculosis treatment was high. A majority of participants were earn monthly income ≤500 ETB and respondents were uneducated. A majority of the pregnant women have experience of side effects and were have headache and dizziness type ani-TB medication side effects. Regarding the reason for missing anti-TB medication majority were forgetfulness followed by were vomiting and diarrhea and cost of transport.

Acknowledgment

We had gratitude to study participants and data collectors.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest.

References

- Das R, Baidya S, Das JC, Kumar S (2015) A study of adherence to DOTS regimen among pulmonary tuberculosis patients in West Tripura District. Indian J Tuberc 62(2): 74-79.

- WHO (2017) Global tuberculosis report. WHO press, Geneva, pp. 147.

- WHO (2017) Multi drug resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB). UpToDate WHO Global tuberculosis program.

- WHO (2018) Global Tuberculosis Report. pp. 1-162.

- WHO (2004) Stop TB Dept. and World Health Organization. Dept of HIV/AIDS. Interim policy on collaborative TB/HIV activities. Geneva, pp. 19.

- FDRE, MOH (2012) Guidelines on Programmatic Management of Drug Resistant Tuberculosis in Ethiopia. Ministry of Health of Ethiopia, Ethiopia.

- Hou W, Song F, Zhang N, Dong XX, Cao SY, et al. (2012) Implementation and community involvement in DO TS strategy: a systematic review of studies in China. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 16 (11): 1433-1440.

- WHO (2019) Global Tuberculosis report 2019. pp. 1-283.

- El Sahly H, Wright J, Soini H, Bui TT, Williams Bouyer N, et al. (2004) Recurrent tuberculosis in Houston, Texas: A population-based study. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 8(3): 333-340.

- Maartens G, Wilkinson R (2007) Tuberculosis. Lancet 370(9604): 2030-2043.

- Sabate E (2003) Adherence to long-term therapies: evidence for action: World Health Organization.

- Awofeso N (2008) Anti-tuberculosis medication side effects constitute major factor for poor adherence to tuberculosis treatment. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 86(3): B-D.

- SIAPS U (2017) The economic cost of non-adherence to TB medicines resulting from stock-outs and loss to follow-up in Kenya.

- WHO (2011) Guidelines for intensified tuberculosis case-finding and isoniazid preventive therapy for people living with HIV in resource-constrained settings. Department of HIV/AIDS stop TB department, Geneva.

- WHO media center (2015) Tuberculosis fact sheet. Geneva.

- WHO (2006) The Global Plan to Stop TB 2006-2015. Geneva.

- Rieder LH (2002) Interventions for tuberculosis control and elimination. Journal of International Union against Tuberculosis and Lung Diseases 5.

- Gube A, Debalkie M, Seid K, Bisete K, Mengesha A, et al. (2018) Assessment of anti-TB drug nonadherence and associated factors among TB patients attending TB clinics in Arba Minch governmental health institutions, southern Ethiopia. Tuberculosis Research and Treatment 2018: 7.

- World Health Organization (2013) Adherence to long-term therapies. Am J Hosp Palliat Med 30: 334-338.

- Woimo TT, Yimer WK, Bati T, Gesesew HA (2017) The prevalence and factors associated for anti-tuberculosis treatment non-adherence among pulmonary tuberculosis patients in public health care facilities in South Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. BMC public health 17(1): 269.

- WHO (2011) Global tuberculosis control report 2009. Global tuberculosis control 2011.

- Zegeye A, Dessie G, Wagnew F, Alemu Gebrie, Sheikh Mohammed Islam, et al. (2019) Prevalence and determinants of anti- tuberculosis treatment non-adherence in Ethiopia: a systematic review and meta- analysis. PLoS One 14(1): e0210422.

- WHO (2011) WHO report 2011/Global Tuberculosis Control, WHO, Europe.

- Ministry of Health of the People’s Republic of China (2018) National TB Control Program Implementation Guide in China. Peking Union Medical College Press, China.

- Ubajaka CF, Azuike EC, Ugoji JO, Onyema E Nwibo, Obiorah C Ejiofor, et al. (2015) Adherence to drug medications amongst tuberculosis patients in a tertiary health institution in Southeast Nigeria. International Journal of Clinical Medicine 6(6): 399-406.

- Monica G, Amuha PK, Kitutu FE, Odoi Adome R, Kalyango JN (2009) Non-adherence to anti-TB drugs among TB/HIV co-infected patients in Mbarara Hospital Uganda: prevalence and associated factors. Afr Health Sci 9(1): S8-S15.

- Kebede A, Wabe NT (2012) Medication adherence and its determinants among patients on concomitant tuberculosis and antiretroviral therapy in Southwest Ethiopia. North American Journal of Medical Sciences 4(2): 67-71.

- Begashaw Bayu, Lonsako A, Tegene LD (2016) Directly observed treatment short-course compliance and associated factors among adult tuberculosis cases in public health institutions of Hadiya zone, Southern Ethiopia. Journal of Infectious Diseases and Immunity 8(1): 1-9.

- Eticha T, Kassa E (2014) Non-adherence to anti-TB drugs and its predictors among TB/ HIV co-infected patients in Mekelle, Ethiopia. J Bioanal Biomed 6: 061-064.

- Hui X Fang, Hui H Shen, Wan Qian H, Qi Qi Xu, et al. (2018) Prevalence of and Factors Influencing Anti-Tuberculosis Treatment Non-Adherence Among Patients with Pulmonary Tuberculosis: A Cross-sectional Study in Anhui Province, Eastern China. Med Sci Monit 25: 1928-1935.

- Sewunet H Mekonnen, Woretaw A Azagew (2018) Non-adherence to anti-tuberculosis treatment, reasons and associated factors among TB patients attending at Gondar town health centers, Northwest Ethiopia. Mekonnen and Azagew BMC Res Notes 11(1): 691.

- Ruru Y, Matasik M, Oktavian A, Senyorit R, Yunita M, et al. (2018) Factors associated with non- adherence during tuberculosis treatment among patients treated with DOTS strategy in Jayapura, Papua Province, Indonesia. Glob Health Action 11(1): 1510592.

- Alemayehu A Gube, Debalkie M, Seid K, Bisete K (2018) Assessment of Anti-TB Drug Nonadherence and Associated Factors among TB Patients Attending TB Clinics in Arba Minch Governmental Health Institutions, Southern Ethiopia. Tuberculosis Rese arch and Treatment 2018: 7.

- Kiros YK, Teklu T, Desalegn F, Tesfay M, Klinkenberg E, et al. (2014) Adherence to anti-tuberculosis treatment in Tigray, Northern Ethiopia. Public Health Action 4(4): S31-S36.

-

Gudisa Bereda, Gemechis Bereda. Determinant of, and Factors Influencing Medication Poor Adherence to Pulmonary Tuberculosis Treatment at The Tuberculosis Clinic of Mettu Karl Referral Hospital, Southwestern Oromia, Ethiopia: A Prospective Cross Sectional Study, 2021. Archives in Respiratory & Pulmonary Medicine. 1(1): 2021. ARPM.MS.ID.000501.

-

Tuberculosis, Poor adherence, Associated factors, Medication, TB clinic, Public health, Mettu Karl Referral Hospital, Ethiopia

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.