Research Article

Research Article

Market For Organic Products of Animal Origin in Brazil

VLV Woiciekowski*

Bachelor in Veterinary Medicine - PUCPR, Bachelor in Biomedicine - University Center UNIBTA, Master in Agroecology - UEM, Post-graduate in Ruminant Nutrition - FAZU, Post-graduate in hygiene and inspection of Products of Animal Origin - UNYLEYA, Post-graduate Graduated in Internal Medicine and Surgery of Small Animals – Quallites Postgraduate Institute, Student of the Bachelor’s Course in Nutrition University Center ETE, Student of the MBA in Business Administration – Iguazu College, Student of the MBA in Marketing – Iguazu College, Student of the MBA in Consumer Behavior - Iguazu College, Brazil

VLV Woiciekowski, Bachelor in Veterinary Medicine - PUCPR, Bachelor in Biomedicine - University Center UNIBTA, Master in Agroecology - UEM, Post-graduate in Ruminant Nutrition - FAZU, Post-graduate in hygiene and inspection of Products of Animal Origin - UNYLEYA, Post-graduate Graduated in Internal Medicine and Surgery of Small Animals – Quallites Postgraduate Institute, Student of the Bachelor’s Course in Nutrition University Center ETE, Student of the MBA in Business Administration – Iguazu College, Student of the MBA in Marketing – Iguazu College, Student of the MBA in Consumer Behavior - Iguazu College, Brazil.

Received Date: February 16, 2023; Published Date: March 07, 2023

Annotation

The objective of this work is to carry out a systematic review of the literature on studies of Organic Certification Processes in Brazil, seeking to focus on products of animal origin. The production of organic food produced optimizes the use of natural and socioeconomic resources and fundamentally respects the culture of rural communities. It also values economic and ecological sustainability, increased benefits, minimizes the use of non-renewable energy, without using synthetic materials or genetically modified organisms. The work is fundamental as it will provide theoretical and methodological subsidies for other students and professionals on the topic Certification of organic animal products in Brazil. First, a general approach will be made regarding the consumption of organic food in the world and in Brazil, followed by an approach regarding organic animal products as well as animal welfare. In a third moment, food security and conventional and organic production systems will be highlighted. In addition, the main legislation that discusses the respective topic in question and the certification processes for organic products will also be addressed.

Keywords: Organic market; Organic meat; Organic products; Food safety

Introduction

Organic foods are produced in the Brazilian context, generally using specific techniques, which essentially seek to adopt natural, socio-economic resources, always respecting the culture of rural communities. In this way, it values economic and ecological sustainability, increased benefits, minimizes the use of nonrenewable energy, without using synthetic materials, genetically modified organisms, or ionizing radiation (BRASIL, 2003). According to the criteria of the Brazilian Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Supply (2020), it classifies that to receive the designation of organic product, it must be in natura or from an organic production system, whether agricultural or resulting from the process aimed at sustainability and does not present any damage to the environment. Despite all the economic crisis generated by the Covid-19 pandemic, the organic products sector recorded a 30% increase in sales in 2020, moving BRL 5.8 billion, according to a survey by Organism- Organic Promotion Association. The year was also marked by the advance of these products to cities in the country’s interior. For the director of organism, Cobi Cruz, the numbers show something more than just a simple passing leap in consumption. “The increase, in itself, is not new, as organic products quadrupled their sales between 2003 and 2017 and grew 15% in 2019. In fact, these 30% achieved in times of crisis point to a trend: the consolidation of a new scenario, in which healthy eating, sustainability and socially fairer production relations are gaining ground in society as a whole”, he says (ABRAS, 2021).

The COVID-19 outbreak that occurred 2020/2021 has drastically changed people’s lifestyle. People tend to choose healthier foods because the wrong eating habits can lead to susceptibility to the virus itself [1]. It is also worth mentioning that organic animals must be raised in large areas of native pastures, respecting animal welfare and treated only with Homeopathic and Herbal Medicines. Furthermore, the production is certified by the IBD, the meat is processed by the JBS Friboi group, following all quality and food safety standards [2], FIGUEIREDO E SOARES, 2012). Finally, the objective was to carry out a systematic review of the literature on studies of Organic Certification processes in Brazil, with emphasis on Products of Animal Origin. Several aspects contributed to people seeking this type of food, it became a healthy option, which were gradually incorporated into the quality of life of consumers in their daily lives. This gradual expansion took place in Europe, North America and China became the fourth country to consume organic products. There is considerable growth, mainly in countries in Europe and America [3]. According to data from the Institute of Applied Economic Research (IPEA). (2020), the average annual growth in retail sales of organic products in the world was greater than 11%, an indicator that expresses the dynamism of this sector, especially when comparing this result to data on sales of non-organic basic agricultural products. It should be noted that demand, whether national or international, tends to grow over the next few years, as organic products are being associated with a higher level of food security and quality of life [3].

Material and Methods

The bibliographical survey of the present research is promoted through the scientific literature, focusing on the works published on the Certification of Organic Animal Products in Brazil between 1985 and 2022 in Brazil. According to Gil (2008, p. 50) bibliographical research “is developed from material already prepared, consisting of books and scientific articles’‘.

Mapping was carried out through systematic searches in national and international databases, including:

It was established a priori as an inclusion criterion only articles available in Portuguese, complete works published between 1985 and 2022. In accordance with the exclusion criteria, publications dated before, in a foreign language, incomplete works such as summaries, reviews and publications that did not articulate with the theme proposed in the present study. The 106 titles initially obtained by the bibliographical survey were read, and among those selected that appear in the bibliographical references, as they were more broadly articulated to the theme proposed in this article.

Results

In the Brazilian context, the organic and/or agroecological market has its origins in the late 1970s, when there was a set of local initiatives that sought healthy alternative food, and a conservative modernization began to flourish [4]. However, in different states, several NGOs in partnership with social movements and organizations of family farmers also fought for this type of sustainable agriculture. In 2003, Law 10,831 was approved, which provides for organic agriculture in Brazil. The law in question constitutes a guiding axis of the regulatory framework, covering different types of alternative systems – ecological, biodynamic, natural, regenerative, biological, agroecological, permaculture and others. This law was one of the most important, as it projected Brazil at an international level as one of the countries that made the most progress in favor of organic production and marketing [4]. According to the Nutrition Business Journal (2017), organic food sales in the United States increased from approximately US$11 billion in 2004 to approximately US$27 billion in 2012. In 2010, the United States overtook the European Union as the largest market for organic products in the world. world. That is, in less than ten years, the United States has doubled its revenue sources with organic products. In 2017, the United States is approaching $50 billion in revenue from organic products [5].

Foot Notes1Information taken from the site Organis.org.br

It is well known that the world has been following a trend of consumption for products that have natural and organic characteristics and that have characteristics inherent to well-being and health. Tandon (2021) stresses that consumers’ search for food grown in sustainable ways, such as agroecological and organic products, is constantly growing. Gradual but extensive growth has been seen around the world in demand for organic food (Sultan et al., 2020) with global sales exceeding $90 billion over the last twenty years. In 2015 agroecological agriculture is still not very present in scale in the world, contributing only 0.98% when compared to the conventional system, the countries with the greatest emphasis on certified organic production are Australia and European countries such as Finland, Spain, and Italy. However, when we think in numbers of certified organic producers to a domain in India’s Certification Ranking with 650,000 producers. In America, Mexico stands out with 169,703 producers. Europe is strongly represented by Italy with 45,969 producers, Uganda with 189,610 producers, Tanzania 148,610 producers and Ethiopia 134,626 producers are the representatives of Africa that has been standing out in certified organic production [4]. Another important data highlighted by the Ipea survey (2019) is the significant growth in the number of producers, which was around 253 thousand worldwide, already in 2000, reached almost 2.9 million in 2017. occurred mainly in Asia, Africa, and Latin America. These data indicate that the market grows every year.

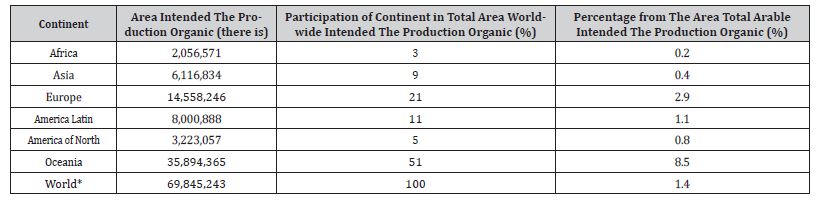

The sale of organic products in these countries totaled 55.1 billion US$ in 2019, an increase of 5% compared to the previous year [6]. The main countries that consume organic products in the world are: United States, Germany, France, China, Canada, United Kingdom, Italy, Switzerland, Spain, and Japan. (Forbes, 2015). China is Asia’s biggest organic food market, totally dominating the region’s market. In 2018, the total sales of organic food (including beverages) in China were 63.5-billion-yuan, accounting for 0.8% of the total food consumption expenditure of 7.86 trillion yuan [7]. Below are the percentages of the continents in the world area devoted to organic production in 2017 (Table 1).

Table 1: Area intended the production organic, participation of continent at area total worldwide intended the production organic It is percentage from the area total arable intended for production organic us continents (2017).

It can be seen in this table that from 2000 to 2017, the arable area worldwide that was destined to organic crops increased significantly by 365%, almost 10% to the year (aa). In this way, it is noticed that the agriculture organic took a leap from 15 million hectares of land to 69.8 million hectares in the same period. Another continent that advanced was Oceania, with a total of 51% of the agricultural area destined for organic production located in Oceania, then for the Europe (21%), America Latin (11%), Asia (9%), America of North (5%) and Africa (3%). Even though there was a significant increase, the percentage in relationship to the total from the extension of lands agricultural available in the regions, is still small: in 2017, only 1.4% of the world’s arable land was destined to organic crops worldwide (Table 2).

Table 2: Evolution of areas destined the production organic, in between 2007 It is 2017, of the twenty countries with to the bigger extensions in area in 2017.

It is possible to verify in this table, that there was a considerable and significant evolution of the world organic production, in agricultural land destined to this specific production. This perspective presents a situation that offers a differentiated picture, due to Australia, Argentina, and China, being the first ones highlighted, since they have only 8.8%, 2.3% and 0.6% of their agricultural land specifically destined to organic production, respectively. However, some countries were able to surpass the percentage of 10% of their agricultural area in this type of production (Table 3).

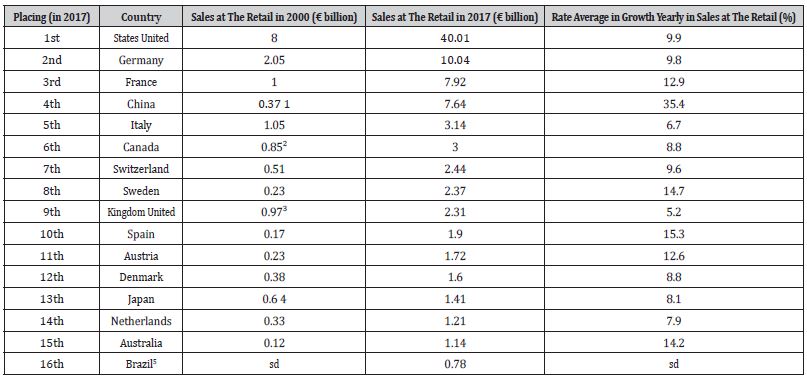

Table 3: Countries with to the bigger sales in organic at the retail of world (2017).

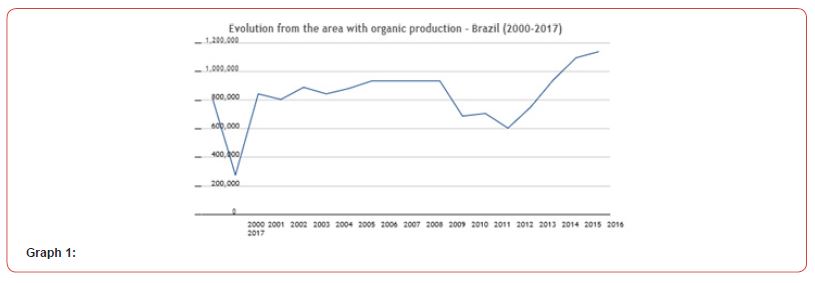

Although the year 2000 sales data in Table 3 is available only for your countries Europeans, The Australia It is you States United States, research in this area characterized the production It is from the demand per products highlighted in this period, emphasizing that the big potential in sales on the Asian continent, there was significant growth in the Indian and Chinese markets. In between 2000 and 2017, there was a significant growth of 15.3% in Spain, 14.7% in Sweden and 14.2% in Australia. Since this trend also he can be seen in the growth of per capita consumption of organic products (Graph 1).

Willer and Lernoud (2019) point out that the area agricultural Brazilian with production organic in the Brazilian context was around 1,209,773 acres, in 2011, with areas considered organic areas intended specifically for beekeeping and extractivism, emphasizing that the production and collection of chestnuts.

Discussion

The quality of organic foods in the Brazilian context makes it possible to group essential aspects in choosing those most suitable for the health of humanity, and aspects related to nutritional, sanitary and environmental quality. Due to this aspect, quality food should be consumed, and it should be a habit that is increasingly incorporated worldwide. It is possible to state that the certifications make it possible to use an instrument whose application is beneficial to the consumer, not only in terms of the quality of the agri-food product, but essentially in the production processes that generated it from the choice and perspective of respect and protection of the environment, animal welfare, fair trade, etc. Regarding organic products, whose qualities are not initially noticeable, this standardization requires an external entity that attests, that is, a certification that respects the established criteria of the legislation [8]. The last three decades have significantly increased organic or ecological production worldwide, both from the point of view of cultivated surface and the adhesion of the number of farmers identified with this way of producing ecologically.

Organic products are accredited according to the International Federation of Organic Agriculture Movements (IFOAM), which is the international federation that establishes the various movements related to organic agriculture. Remembering that when referring to standardization, it is important to emphasize that each country must adhere to the internal legislation and regimes of each country. Example: In the United States, there is a new certification model called ROC - Regenerative Organic Certified (ROC) - it uses the organic certification of the United States Department of Agriculture as a base and then adds other criteria for health and well-being. being of the soil, of the animals and also, of the worker. Some international certifiers that operate in Brazil are: BCS Oeko Garantie (Germany); Ecocert Brazil (France); International Agricultural Organization (Argentina); Ecological Market Institute (Switzerland); FVO Brazil (United States); Imaflora (United States); Skal Brazil (Holland) and AB (France). The Brazilian experience represents an indisputable reference at the international level, particularly after being enshrined in law as a type of certification recognized as equivalent to certification by a third party in terms of effects and application. The theme arouses great interest, providing a great academic production [9].

According to Souza’s understanding (1998), one of the ways to guarantee the consumer the quality of a product and the producers to preserve themselves from disloyal competitors is through an organic certification seal. That is, the seals certify the origin of the organic product and help the consumer when making a purchase decision, reducing information costs for society, and increasing the efficiency of the organic food market [10-20]. According to the procedures by which a certifier, accredited by the Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Supply (MAPA) and accredited by the National Institute of Metrology, Standardization, and Industrial Quality (Inmetro), must ensure in writing that a given product complies with Brazilian legislation and organic production practices. Such laws must comply with the current technical regulations specific to the Brazilian context, that is, the products included in the Brazilian Organic Conformity Assessment System must also comply with the determinations for labeling organic products and bear the seal of this System. Thus, the certification is presented in the form of a stamp affixed or printed on the label or packaging of the product [21-35].

In short, it appears that organic production in the Brazilian context has been growing, but still at a slow pace ( TERRAZZAN; VALARINI, 2009 ). Although Law n. 10,831 essentially seeks to support the producers of these products, providing support to the growing demand for organic products, according to data from the Institute for the Promotion of Development – IPD Organic (2011) [36-40].

FootNotes2 There is wide controversy about the terminology used: organic products and ecological products. It is a terrain of disputes both on the academic and political-ideological levels. As is known, the adjective organic was enshrined in the new Brazilian legislation and it is for this reason that we chose to use it, even though we are aware of its limitations. Objectively, products derived from petroleum can be considered organic in nature (hydrocarbons), despite being diametrically opposed to the fundamentals of production on an ecological basis. It is not our purpose to enter into the terrain of this debate. In Europe, the term ecological is predominant, so we chose to use it in order to be faithful to the sources of information on which this study is based, whether they are of a primary or secondary nature.

3We refer to Law n. 10,831 of 12/23/2003 regulated by Decree n. 6,323 of 12/27/2007. This legislation is structured around the creation of the so-called “Brazilian Organic Conformity Assessment System” (SisOrg), managed by the Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Food Supply (Mapa), made up of bodies and entities of the federal public administration and assessment bodies of compliance, providing for two major certification modalities, namely: audit certification and Participatory Guarantee Systems, in addition to social control bodies (OCSs) that correspond to the case of direct sales of groups of family farmers duly registered with this ministry.

Conclusion

It is concluded that the Organic Certification Processes in Brazil seek to focus on the issue of organic food is gradually growing nationally and also worldwide, however, to guarantee the quality and origin of these products, we have some specific laws that establish different processes of certification, which is the procedure by which a certifier, duly accredited by the Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Supply (MAPA) and “accredited” (accredited) by the National Institute of Metrology, Standardization and Industrial Quality (Inmetro), ensures in writing that a given product , process or service complies with the norms and practices of organic production. In this way, food produced by the organic system cannot have artificial inputs such as pesticides, hormones, antibiotics, chemical fertilizers, veterinary drugs, and genetically modified organisms, but must enable broad actions that seek to conserve natural resources, taking into account the ethical aspects present in this place, such as the internal social relations of the property and also the treatment of animals [41-60].

Acknowledgment

None.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest.

References

- Bracale R, Vaccaro CM, (2020) Changes in Food Choice Following Restrictive Measures Due to Covid-19. Nutrition, Metabolism and Cardiovascular Diseases 30(9): 1423-1426.

- Brazilian Association of Organic Livestock (ABPO) (2012) Interview with President Leonardo Leite de Barros. Period from 03 to 10 May 2012. Campo Grande–MS.

- Lima et alii, Sandra Kitakawa, (2020) TD 2538 - Production and Consumption of Organic Products in the World and in Brazil.

- IPEA (2020) Growing demand encourages organic production in Brazil and worldwide.

- Organis (2018) Global Organic Food and Beverage Market to Triple By 2024.

- Willer H, Lernoud J (Eds.) Lozano Cabedo C (2009) The attributes of organic foods: distinction, quality, and safety. In: Simon X, Copena D. (Coords.), Building an agroecological rural, Vigo, University of Vigo, Servizio de Publications, pp. 317-334.

- The world of organic agriculture. Statistics and emerging USDA–United States Department of Agriculture.

- IFOAM – Organics International (2020) The World of Organic Agriculture Statistics and Emerging Trends 2020. Edited by Helga Willer, Bernhard Schlatter, Jan Trávnícek, Laura Kemper and Julia Lernoud.

- Buainain AM, Batalha MO (2007) Productive Chain of Organic Products. Brasilia: Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Supply (MAPA); Agricultural Policy Secretariat (SPA); Inter-American Institute for Cooperation on Agriculture (IICA). Agribusiness Series, 5.

- ABPA (2018) Annual Report.

- Organic sector grows 30% in Brazil in 2020.

- Allaire G, Sylvande B (1997) Qualité specifique et systèmes d' innovation territoriale. In: Cahiers d' Economie et Sociologie Rurales 44: 29-59.

- Almeida VES, Carneiro FF, Vilela NJ (2009) Pesticides in vegetables: food safety, socio-environmental risks, and public policies for health promotion. Tempus: Actas in Collective Health, Brasília, DF 4(4): 84-99.

- Altieri, Miguel (2012) Scientific bases for sustainable agriculture. São Paulo. Popular expression.

- Annualpec (2017) Yearbook of Brazilian livestock. Sao Paulo: FNP Institute.

- Appleby MC, Mench JA, Olsson IAS, Hughes BO (2011) Animal Welfare, 2nd, Wallingford: Cabi.

- Assis RL (2003) Globalization, sustainable development, and local action: the case of organic agriculture. Cadernos de Ciência & Tecnologia, Brasilia 20(1): 79-96.

- Azevedo E (2006) Organic food: expanding concepts of human, social and environmental health. Shark: Unisul.

- Azevedo E, Rigon SA (2010) Food system based on the concept of sustainability. In: Taddei JA, Lang RMF, LongoSilva G, Toloni MHA, eds. Public health nutrition. São Paulo: Rubio, pp. 543-60.

- Barros JDS, Silva MFP, (2010) Sustainable Agricultural Practices as Alternatives to the Hegemonic Production Model. Society and Rural Development on line 4(2).

- Baudry J, Julia Baudry, Karen E Assmann, Mathilde Touvier, Benjamin Allès, Louise Secondaet al. (2018) Association of frequency of organic food consumption with cancer risk findings from the NutriNet-Santé prospective cohort study. JAMA International Medicine, Chicago 178 (12): 1597-1606.

- Borguini RG, Torres (2006) EAFS Organic food: nutritional quality and food safety. Food and nutrition security. Campinas.

- Borguini RG, Tomato (Lycopersicum esculentum Mill) organic: nutritional content and consumer opinion. Piracicaba, 2002. Master's Degree (Agronomic Engineering) ESALQ/USP.

- Bourn D, Prescott J (2002) A comparison of the nutritional value, sensory qualities, and food safety of organically and conventionally produced foods. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 42(1): 1-34.

- Brazil (2021) Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Supply (MAPA).

- Brazil (2007) Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Supply. Technical information. Brasília, DF.

- Buainain AM, Batalha MO (2007) (Coord). Productive Chain of Organic Products. Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Food Supply MAPA, Agricultural Policy Secretariat SPA, Inter-American Institute for Cooperation on Agriculture IICA, Brasilia: IICA, 5. (Agribusiness Series).

- Caldas ED, Souza LC (2000) Chronic risk assessment of pesticide residue ingestion in the Brazilian diet. Rev. Public Health 34(5): 529-537

- Caleman, Silvia Morales de Queiroz (2010) Coordination Failures in Complex Agro-industrial Systems: an application in the beef agroindustry. Thesis (Doctorate)-University of São Paulo-USP, São Paulo, São Paulo.

- Embrapa (2003) Broiler Chicken Production. pp. 1.

- (1985) EPA (Environmental Protection Agency). Pesticide safety for farmworkers. Washington DC: United Sates Environmental Agency, Office of Pesticide Programs.

- (2003) FAO - Food and Agriculture Organization of The United Nations; WHO - World Health Organization. Safety assessment of foods derived from genetically modified animals, including fish. Rome. (Food and Nutrition Paper, 79).

- (2010) FAO – Food and Agricultural Organization. The second report on the state of the world’s plant genetic resources for food and agriculture. Roma: Commission on Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture.

- Ghini R, Bettiol W, Hamada E (2011) Diseases in tropical and plantation crops as affected by climate changes: current knowledge and perspectives. Plant pathology 60: 122-132.

- Howard SA (2012) A testament agricultural. 2 ed. São Paulo, SP: Expressão Popular pp. 360.

- IFOAM – Organics International (2018) The World of Organic Agriculture Statistics and Emerging Trends 2018. Edited by Helga Willer and Julia Lernoud.

- IDEC – Brazilian Institute of Consumer Defense (2010) How much do you want to pay? Idec Magazine, São Paulo 142: 16-20.

- IFOAM - International Federation of Organic Agriculture Movements (2005) The principles of organic agriculture. Bonn.

- IPCC – Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (2007) Fourth assessment report.

- Jensen TK, Giwercman A, Carlsen E, Scheike T, Skakkebaek NE (1996) Semen quality among members of organic food associations in Zealand, Denmark. Lancet 347(9018): 1844.

- Kazioski GV, Ciocca MLS (2000) Energy and Sustainability in Agroecosystems. Rural Science, Santa Maria 30(4): 737–745

- Lages AMG, Barbosa LCBG (2008) The commercialization of organic products in the agroecological fair of Maceió/AL: an evaluation under the logic of the theory of transaction costs. In: 46th Congress of the Brazilian Society of Economics, Administration and Rural Sociology. Rio Branco - AC, 2008. Anais... Rio Branco: SOBER.

- Lairon D (2009) Nutritional quality and safety of organic food. The review. Agron Sustain Dev 30(1): 33-41.

- Linder NS, Uhl G, Fliessbach K, Trautner P, Elger CE, et al. (2010) Organic labeling influences food valuation and choice. Neuroimage 53: 215-220.

- MAP (2021) Organic product certification manual.

- Mazzoleni EM, Nogueira JM (2006) Organic agriculture: basic characteristics of its producer. Journal of Rural Economics and Sociology. Rio de Janeiro 44(2): 263-293.

- Mazzuco H (2008) Sustainable actions in egg production. Brazilian Journal of Zootechnics. Viçosa, 37.

- Meireles LR, Rupp LCD. Ecological Agriculture-Basic Principles. 205.

- Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Supply.

- Neves MF, Zylbersztajn D, Machado Filho CP, Bombig RT (2002) Collective Actions in Networks: The Case of Beef in Brazil. In. Trienekens, JH & Omta, SWF (ed.). Paradoxes in Food Chais and Networks. Wageningen academic Publishers, pp. 742–750.

- Oliveira, LHS de, (2003) Market for Organic Products in Europe: An Exploratory Study of Investment Alternatives for Brazilian Sustainable Agribusiness. 2003. 136 f. Completion of course work (Master's) – Federal University of Pernambuco, Recife.

- Pan American Health Organization (1997) Manual for health surveillance of populations exposed to pesticides, pp. 1-72.

- OIA Brazil (2021) International Agricultural Organization.

- Penteado Silvio Roberto (2011) Rural producer series: Organic agriculture. 2 ed. USP: Esalq, pp. 1-40.

- Penteado SR (2012) Implementation of organic cultivation: planning and planting. 2nd ed. Campinas: Via Orgâ

- Schmitt CJ (2011) Shortening the path between food production and consumption. Agriculture Magazine. Rio de Janeiro 8(3).

- Soares JPG, Aroeira LJM, Fonseca AHF, Fagundes GM, Silva JB (2011) Organic milk production: challenges and perspectives. In: Marcondes, MI et al. (Org.). Anais do III National Symposium on Dairy Cattle and I International Symposium on Dairy Cattle. 1 ed. VIÇOSA: Suprema Grafica e Editora 1: 13-43.

- Souza MCM (1998) Organic cotton: the role of organizations in coordinating and differentiating the agro-industrial cotton system. SP: FEAC, 1998. Originally presented as a master's thesis, University of São Paulo - Faculty of Economics, Administration and Accounting.

- Sperb P (2017) How the MST became the largest producer of organic rice in Latin America. BBC Brazil.

- State (1994) Journal of nutrition Education. 26(1): 26-33.

-

VLV Woiciekowski*. Market For Organic Products of Animal Origin in Brazil. Arch of Repr Med.. Med. 1(2): 2023. ARM. MS.ID.000510.

-

Organic market, Organic meat, Organic products, Food safety, Organic products, Organisms, Organic foods, Agriculture, Herbal medicines, Animal origin, Organic agriculture

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.