Research Article

Research Article

Academic Governance Networks in the COVID-19 Era

Javier Carreón Guillén1, Cruz Garcia Lirios2*, Francisco Espinoza Morales3 and Gilberto Bermudez Ruíz4

1Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México

2Universidad Autónoma del Estado de México

3Universidad de Sonora

4Universidad Anahuac del Sur

Cruz Garcia Lirios, Universidad Autónoma del Estado de México.

Received Date: March 21, 2023; Published Date: March 31, 2023

Annotation

As of January 2023, the pandemic has claimed the lives of more than four million. In Mexico, confirmed cases of around a million victims accumulate. In this scenario, the Mexican State has escalated into a conflict with Higher Education Institutions regarding the return to classes. While educational policies revolve around lack of refinement and return to classes, even when young people do not have the basic immunization scheme, public universities lead the practice of the virtual classroom. The objective of this work is to analyze and discuss the differences between the public administration of education and the autonomy of the universities regarding the return to the traditional classroom. A literature review was carried out considering the link between policies to mitigate and contain the pandemic in relation to the protocols for returning to face-to-face classes followed by public universities. Axes, trajectories and relationships between risk prevention, self-care and co-responsibility stand out. In relation to the state of the art, the asymmetries between political and educational actors are discussed.

Keywords: Covid-19; Governance; Social Representations; Educational Policy; Pandemic; Agenda

Introduction

Until January 2023, the pandemic has killed more than four million people in the world [1]. In Mexico, it has claimed the existence of about a million [2]. Both contexts reflect the mitigation and containment policies that governments have implemented in the face of the health crisis [3]. In this way, the mitigation and containment policies for the SARS CoV-2 coronavirus and the Covid-19 disease have focused their attention on the distancing and confinement of people. In this sense, the public administration of educational services guided the transition from the traditional classroom to the electronic blackboard. This educational policy changed once immunizations increased, even though young people have not been vaccinated against Covid-19. In response to this policy, the most important public universities in Mexico have decided to remain in a distance system. Both conflicting positions have been exacerbated by the complaint by the federal prosecutor’s office to prosecute academic researchers for administrative violations of their collective contract. This is how the asymmetries between the State and public universities have escalated to reach legal instances to resolve their differences [4]. This section presents the theoretical axes and conceptual matrices for the analysis of the return to the face-to-face classroom, considering a review of empirical studies, as well as deconfinement policies [5]. It is proposed to address the differences between the parties from international guidelines and standards applied in other latitudes and that can be imported to the case of Mexico. The scope and limits of these deconfinement policies are pointed out, considering the perspective of social representations as a reducing panorama of asymmetries between the parties and as an orientation of dispute resolution mechanisms.

The transition to governance lies in the identification of the conflict and the recognition of this situation between the parties [6]. Once the scenario of asymmetric relations has been established, conflict management can be oriented towards the establishment of negotiations, recognition of the common problem, as well as possible alliances to overcome shared adversity. Then, the rounds of negotiations with or without follow-up between the parties can be reoriented towards a consensus. If the parties involved consider that the common problem depends on their resources, they will reach an agreement. Now, when one of the parties assumes that the resources are inferior to the common demands or problems, then dissent emerges. Dissent does not mean the exhaustion of negotiations between the parties, although it is directed towards the relativization of common problems and towards the exercise of power by the State as a reflection of its stewardship [7]. It is a social representation of conflict, agreement and co-responsibility that depends on the input, processing, and communication of information to reach agreements.

Special mention for the governance of the commons and corporate governance which, unlike governance, are disseminated as emblematic cases of pandemic management [8]. The government of the commons differs from governance in that it poses an extremely fatalistic scenario where the only resolution of differences lies in the adoption of common resource management. In the government of common goods, problems can be assumed as irreversible. Furthermore, management is a transitory instrument of risk appetite. Consequently, the parties involved know that in one way or another they will end up merged in the face of a shared problem. This co-management model is positioned as a permanent resolution without the possibility of transition to governance or corporate governance. This is so because the government of the commons is committed to collaboration between the parties. Such an assignment suggests a system of expected resource scarcity and consequent optimization (Spinoza, 2021).

Corporate governance, unlike commons governance, aspires to spread its influence on other systems [9]. In this way, corporate governance focuses its interest on reconciling the growing and expansive interests of the parties in conflict. As the political and academic actors configure a corporation, they reduce their differences until they reach an isomorphism. These are protocols that institutions follow as the central matrix develops. The governments of the commons were questioned by the theory of social representations by proposing a tragedy of the commons [10]. In a scenario of risk events, resources tend to decrease as the problem unites the parties involved. In the end, the theory states that one of the parties will choose to eliminate the other to guarantee their stay. Faced with this criticism, the government of the commons has shown that the more the problem intensifies, the more risk-prone it generates, and collaboration replaces unilateralism. Cooperation is exalted before competition, guaranteeing the survival of the parties involved.

In a government of common goods, the academy could not do without the State in that it supplies the resources [11]. In the same way, the public administration cannot do without the academy because it legitimizes its spending of resources and encourages contributions. Rather, the government of the commons supposes a null autonomy of the universities. Even the collaboration suggests optimization schemes that the academy cannot guarantee due to variable research spending. Therefore, corporate governance as State influence in universities is a more viable alternative than the governance of the commons [12]. It is a decision scheme dictated from the regime, form of state or political system. The academy is an intermediary of state decisions, as well as the optimization of resources determined from the public administration. University autonomy persists, but social policy has a direct influence on the evaluation, accreditation, and certification of HEIs. In this way, corporate governance is an effective state management instrument to legitimize the results of managing the pandemic in terms of infected, sick, and dead (Carreon (2021).

A talent training system for its conversion into intangible assets of knowledge-creating organizations [13]. This is the definition of corporate governance in which state policies are legitimized through knowledge. It is a system of co-management of demands and resources. State and academia converge in the formation of human capital with emphasis on their intellectuality and creativity. In the face of the pandemic, the parties involved are interested in reducing risks, but immunization is exhausting. Therefore, the State is committed to a cultural and creative city policy to reactivate its economy. The return to the face-to-face classroom is just one indicator of the post-Covid-19 city project. In this process, corporate governance assumes the establishment of guidelines for attracting talent, human and intellectual capital that very soon should be intangible assets of universities and organizations. In this project, the return is an imperative determined by the policy of reactivating tourism in the cultural city and its entertainment industry.

Both governance of the commons and corporate governance are limited by the symbiosis between the State and academia [14]. This is where governance, understood as the synthesis of a diversity of participation of sectors and actors involved, reaches its relevance. It is about the co-management of demands and resources as the differences between the parties intensify. In other words, greater asymmetries will correspond to management systems, producers, and translators of knowledge. This is so because governance is a flexible system of abilities, capacities, resources, and knowledge oriented towards the coexistence of the parties (Heron (2021). Governance explains the differences between universities and the State [15]. Based on participatory mechanisms, the contribution of actors and sectors distinguishes them from other forms of government. In the case of the pandemic, governance proposes and facilitates discussion on an open agenda. The axes and topics of debate are concentrated in an agenda where the actors and sectors influence each other. It is possible to notice that governance reaches the interdependence between the parties. Unlike governance of the commons and corporate governance that focus on conflict between parties, governance assumes that differences are transitory. In fact, the asymmetries between the parties are the preamble to their participation. There are different conglomerates of participation that imply open or bounded governance [16]. In this way, the pandemic is a situation that activates resources from different sectors. This is the case of the academy as a central actor in the management, production, and transfer of knowledge. It is not fortuitous that public universities bet on the virtual classroom when the State determined the return to face-to-face classrooms. The knowledge that universities accumulate is enough to legitimize their confinement decisions. In contrast, the public administration tries to legitimize its decisions from community and civil participation. Faced with the militants, sympathizers and adherents of the government who adopt the policies of lack of confidence and return to the face-to-face classroom, the academy simply activates its citizen participation from the training of talents.

It is true that corporate governance can become governance as long as the dependency between the State and academia is possible, but governance suggests that such a scheme coexists with other participatory models [17]. Unlike corporate governance that activates management protocols such as biosafety, governance simply opens participatory channels. While corporate governance tries to justify its structure in the face of a contingency, governance suggests that such a threat is necessary for discussion. Other differences between corporate governance and governance can be seen in conflict resolution [18]. Corporate governance requires the unanimous or majority agreement of the actors. Governance is only possible when the parties involved recognize themselves as different. Therefore, corporate governance avoids conciliation or mediation to adopt arbitration. Governance, on the other hand, suggests that none of these management instruments is necessary.

From the government of the commons, it is essential that the vaccines be disseminated among the parties to guarantee the conservation of resources in the face of future contingencies [19]. In contrast, governance only keeps communication channels open to guarantee a discussion that will inevitably generate an agreement based on differences and similarities. It means then that participation is a diversity of criteria and opinions that distinguish the actors and sectors. From this distinction, governance is constructed as a management alternative to the government of common goods. Regarding conflict resolutions, the government of the commons is only sustained from shared objectives, tasks, and goals [20]. Governance is a series of divergent and convergent proposals that regulate themselves. A contribution turns out to be more significant if the previous one is insufficient. A contribution will be more relevant if its predecessor is abandoned by one of the parties. Governance is then expected to be the management system that stakeholders need to settle their differences, consolidate their projects, and develop their capacities.

Governance, by summoning and receiving feedback from existing forms of participation, reaches a status of co-management [21]. This means that it is not built from duality. It is not a unilateral and unidirectional system where one of the parties is hegemonic until the other is emancipated. It is a scenario where participations converge through surrounding information in the media and electronic networks. It is a public agenda open to the discussion of its contents. A global critique of its themes and a systematic review of its elements. In the face of the pandemic, governance is a structure of data and decisions oriented from the proximity of risk events and their aversions as well as their propensities. In its conciliatory mode, governance highlights disagreements to establish common ground soon [22]. In this way, the pandemic is a common problem between the parties. Each one establishes its management criteria, but the extension of the crisis forces the discordant parties to converge in an alliance to reduce the cases. This management principle begins with a truce between state and academia. It continues with a review of the opportunities, challenges, and challenges. Immediately, the concordant parties assume that their common problem intensifies along with their coincidences. Very soon management proposals emerge that overlap with each other. At the end of the process, only those forms of inclusive participation that contributed to the reduction of Covid-19 cases remain.

This is the case of the universities that adopted the policies of distancing and confinement reduced to the virtual classroom [23]. Once immunizations increased, the agreements between the discordant parties also increased until the conflict agenda was reversed into a retributive collaboration. The parties in conflict had never assimilated that their differences would lead to co-management. While their asymmetries diminished, their agreements intensified, not only because of a common problem. A sense of community also emerged that has reduced infections, illnesses and deaths associated with the SARS CoV-2 coronavirus. The key to this resolution lies in the participation from different places and positions. Precisely, governance has been questioned for its degree of openness to the different participants [24]. From this inclusion it is assumed that the actors can only collaborate in the face of an imminent deterioration of their well-being, but the parties would not be opposed without different interests. In fact, it is assumed that governance should be made up of win-oriented participation from all parties. It is true that a crisis activates the sense of community, attachment to place and belonging to a group. The parties to the conflict would not be in that situation without first seeing themselves as exclusive.

From the government of the common goods, it is noted that the interested parties are means of disseminating the differences between those who assume that the goods should be public or private [25]. From corporate governance it is evident that unilateralism allows for consensus. Governance, by betting on the competition of the best ideas, assumes the well-being of those who debate collective action. The parties involved seek their wellbeing from the minor impact of a crisis on themselves and their adversaries. This basic principle of a common enemy makes the parties allies, but it does not guarantee a redistribution of resources based on the vulnerability of the parties.

Therefore, lines of analysis and discussion on the asymmetries between the parties will open the debate on the type of participation that governance requires in the face of a common problem [26]. In the case of the health crisis caused by the Covid-19 disease, the type of participation that would reduce the number of infected, sick, and dead remains to be discussed. The co-management derived from the participation of the actors and sectors will make it possible to anticipate scenarios of imminent risk. The model includes peripheral nodes of social representation that allude to the objectification and anchoring of conflict and resolution [27]. These are instances in which the parties involved generate conflicts, debates, consensus, and dissent to build a management of risk events such as the pandemic. Around this health crisis management node, deconfinement policies are distinguished by calling for the return and normalization of essential activities; productive and cultural. Faced with this federal regulation, Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) are committed to immunizing the community, although the State only considers the vaccination of teachers and administrators to be relevant in a first phase and of students in a second phase.

In the objectification process, the categorization of the parties involved with respect to the resources in the face of the common problem is a relevant phase [28]. This is so because the expectations that the parties have about the conflict and its resolution depend on a comparative management of resources. As one of the parties considers that an abundance of resources prevails, it manages a common problem that can be resolved in the short term. In contrast, a perception of limited resources conditions a position of conflict, negotiation and agreements based on the costs of the problem. From a perspective of social representations as the figurative core of the pandemic, the parties involved assume that the surrounding information determines the demands [29]. If either party assumes that the pandemic has a minimal impact on their resources, then they will support a divided resolution of a conflict. In the case of the academic community, it may see itself as a victim of lockdown policies. By executing a posture of adversity, the academic community builds a figurative core of state power. Then, it relativizes the solutions based on the immunization promoted by the State. In this way, the return to the face-to-face classroom will depend on the history of the relationship between the State and the university (Garcia, 2021).

The interrelation between the figurative core and the periphery of symbolization allows the scope of the conflict between the State and universities [30]. At this point of conflict, the academy posits an asymmetrical relationship with the State, but recognizes resolution passages where the conciliation of interests continued with the non-hostility pact. Both actors, politicians, and academics, can choose to follow the anti-Covid-19 policy, but also to move towards the coupling of resources to reduce the effects of the pandemic on the return to the face-to-face classroom. The cessation of information would indicate a dissent, but the flow of data supposes a possible agreement between academia and the State [31]. In fact, the objectification of the conflict and its categorization as a viable option to consensus or dissent warns of exporting asymmetries to other actors. Once both parties recognize common interests, mediation can be a conflict reduction option. There is a close relationship between the social representation of symbolic categories of power such as selective immunization. It is a categorization of information concerning the vaccination deadlines of academics, students, and administrators. It is true that this site proposes agreements to return to the face-to-face classroom, but there are underlying negotiations around the critical route for lack of confidence.

In the negotiation process between the parties, academia and the state can be overwhelmed by their common problem, which lies in an exponential growth in the number of infected, sick and dead [32]. If this is the case, then the interested parties move towards a renegotiation of their demands, but also towards a readjustment of their resources. Consequently, conciliation and mediation are no longer viable options. Arbitration emerges as the final instance in the renegotiation of the management of the health crisis. In other words, academia and public administration are reorienting the management of the pandemic towards a pragmatic sphere. In this way, the objectification, categorization and anchoring of the conflict are symbolized as opportunities and management barriers between the parties involved [33]. Academia and State assume themselves as managers of a crisis if they symbolize their differences as transitory in the face of an event of permanent risk. In the case of Covid-19, since it is assumed to be a common and transitory problem, it can be represented as a common risk between the parties. Consequently, the urgency of its prevention prevails before any state regulation of lack of confinement or return to the face-to-face classroom.

It is possible to see that a prolonged pandemic, the exponential increase in victims and limited resources make up a fatalistic scenario of risk propensity [34]. According to the theory of social representations, the parties involved will assume the costs of a return to the face-to-face classroom, even when the vaccination scheme is partial, and the victims increase. On the contrary, the most optimistic scenario supposes the concurrence of the parties in the establishment of assertive discourses [35]. Stable communication channels that delimit problems and guide decisions and actions towards co-responsibility. There is a propensity for risk as a hallmark of the asymmetries between the parties and as a consensus between them. To guarantee the continuity of the negotiations, the academy and the State are moving towards a return to the faceto- face classroom. They establish points of agreement that allow clarifying their responsibilities in specific cases of contagion, illness, and death. In fact, they delegate biosecurity to people. In other words, risk prevention is in the hands of individual self-care protocols.

The objective of this paper is to analyze the conflict from the social representations of the actors to discuss the possible ways of mediation, conciliation and arbitration in the resolution of the problem. To be able to contribute to the discussion of political and academic positions, the theory of social representations offers a perspective on which it is possible to reach agreements and coresponsibilities that lead the interested parties towards public health governance in public health spaces. teaching learning such as the traditional and face-to-face classroom. The question that guides the present work is: Can the mitigation and containment policies of the pandemic be oriented towards a distancing and confinement of people that supposes a staggered and safe return for the academic community in the terms that the State demands without disrupting university autonomy?

The premises that guide this study suggest that the differences between the parties reflect their positions in the face of a common problem such as the pandemic [36]. In addition, the conflicts between the actors affect an escalation of negotiation, agreements, and co-responsibilities as a prelude to governance. In this process of management and handling of the pandemic in academic spaces, the parties involved express their positions, as well as their asymmetries. Immediately, the institutional mechanisms of mediation, conciliation and arbitration are activated to reduce the conflict. Mediation as the central axis of a discussion supposes the facilitation of the positions, as well as an orientation towards the reduction of differences based on the knowledge of the demands and the resources between the parties. Conciliation follows the path of mediation. It begins with the recognition of the positions and continues with the contrast of these before a common problem. In this sense, conciliation is a management tool that guides opposing positions from a negotiation of common needs. Therefore, when mediation and conciliation are exhausted, arbitration emerges as a regulated instance of conflict resolution. Based on established protocols, the State and the university community can reach an agreement.

In this way, the contribution of this work includes: 1) a discussion of the conflict between the parties and their resolution mechanisms; 2) a genealogical approximation of the differences and alternatives of co-responsibility between the parties from the social representations; 3) a discussion about the scope and limits of the theoretical perspective in the framework of a governance construction of the return to the face-to-face classroom.

Method

Given that university governance networks are managers of knowledge that is neither established nor consolidated, a documentary, cross-sectional and exploratory study was carried out with a sample of sources identified in national repositories such as Clase, Conacyt, Latindex, Redalyc and Scielo. The observation considered the period from 2019, the year of the emergence of the pandemic until 2023, the year in which the use of face masks is withdrawn. The Delphi Inventory was used, which includes the measurement of five dimensions of governance: conflict (dispositions towards risk prevention), negotiation (attitudes towards risk prevention), agreements (risk prevention), selfregulation (exposure to risks) and co-responsibility (preventive risk systematization). The valid reliability of the instrument was previously established with a sample of students, professors, and administrators. The consistency of the instrument reached values higher than the minimum required of .70 both in the general evaluation and in the evaluations of the subscales.

The keyword search was carried out: “governance” and “COVID-19” in the national repositories, considering the period from 2019 to 2023, as well as the inclusion of findings related to the dimensions of governance in the summary. The Delphi engine was used for the analysis of information. The summaries were coded according to a scale ranging from 0 = “not at all in agreement” to 5 = “quite in agreement”. The data was captured in excel and processed in JASP version 14. The coefficients of normality, reliability, adequacy, sphericity, linearity, and homoscedasticity were estimated. In relation to the structural network, the parameters of centrality and grouping were set.

Results

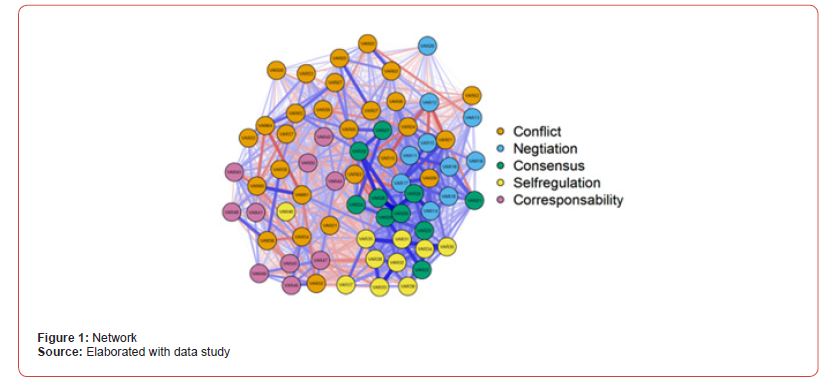

Figure 1 shows the structure of relations between the nodes. It is appreciated that they are limited to the five dimensions of governance reported in the literature. It then means that the selected literature is configured around a process of co-responsibility between the interested parties and that it is implemented in the institution as a reflection of governance (Figure 1).

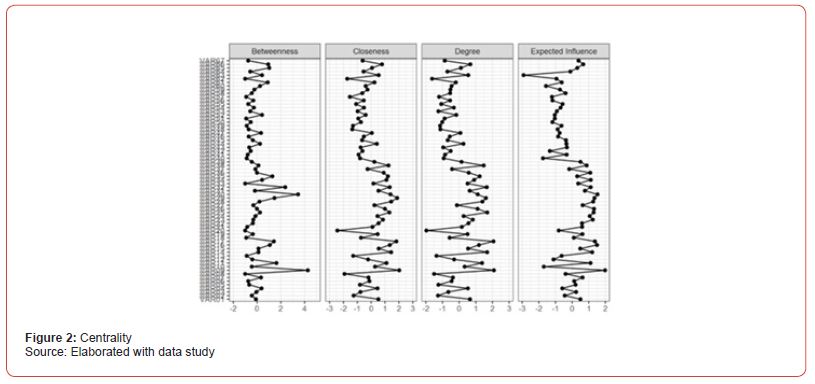

Figure 2 shows the centrality parameters that indicate the possible trajectories between the nodes to configure their elation structure. In other words, governance and its dimensions go through learning paths that allow them to develop governance as a result of their differences in risk prevention (Figure 2).

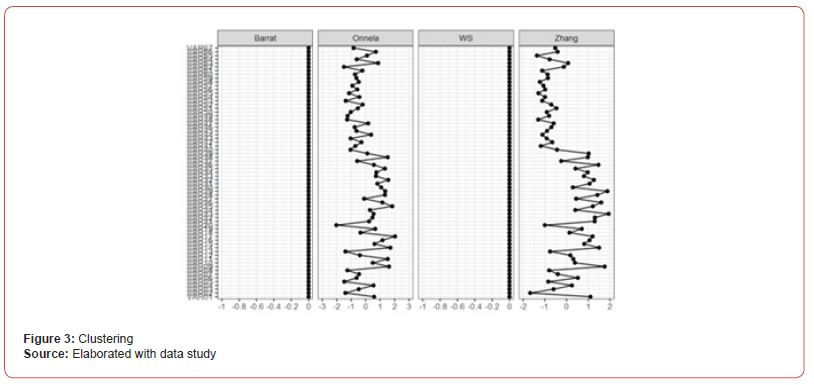

Figure 3 shows that the centrality of the nodes is also oriented towards a main structure that encompasses the findings around a governance that goes from divergences to convergences. That is, the nodal model reflects learning from the asymmetries between the parts. Administrative staff, teachers and students may or may not agree with risk prevention, but in the governance process they learn to tolerate their differences (Figure 3).

The neural network coefficients suggest a governance reflected in the learning of five phases: conflict, negotiation, agreements, self-regulation, and co-responsibility. Consensus is generated from the asymmetries between the parties. In other words, anti- COVID-19 policies generate differences and agreements around risk prevention.

Discussion

The contribution of this work to the state of the question lies in the establishment of a risk prevention learning network in a sample of findings reported in the literature during the period from 2019 to 2023. The results corroborate the null hypothesis regarding the significant differences between the theoretical structure with respect to the observations made. The learning structure suggests knowledge networks. That is, the coding of information in the selected literature is oriented towards a network of nodes where conflicts prevail at the beginning and negotiation and consensus at the end. Unlike systematic reviews and metanalyses where the homogeneous random effects of the preponderant findings in the literature are established, neonatal networks seek to establish the learning of a process of knowledge management, production, and transfer. In this sense, risk prevention is a phenomenon that reflects a latent governance between the parties involved. It is true that the resulting nodes do not allude to self-regulation or co-responsibility, but they do note negotiation and consensus as part of the process. In other words, the review of this study suggests that the selected literature is oriented towards a university governance that consists of risk self-management. Research lines concerning the review of studies that reflect university governance will allow anticipating scenarios of conflicts and agreements. The divergence of opinions as the first condition of governance supposes the prediction of consensus and shared responsibilities.

Conclusions

The contribution of this study to the consulted literature lies in the analysis of a conflict between universities and public administration of higher education. The discussion offered suggests that the parties in conflict can reach consensus and coresponsibility from different management mechanisms such as conciliation, mediation, and arbitration. Underlying this bouquet of offers is governance because of participation in different items and instruments. From the sense of community, participation suggests a management system in which common goods define decisions and actions. Starting from a political ideology, the corresponding participation assumes that the parties will maintain their differences, but in the end the alliances will prevail in the face of a global problem. Considering the appropriation of spaces, citizen participation makes it clear that governance must follow the guidelines of coexistence and equity in the face of the pandemic. Each type of participation suggests to the academic community forms of organization, decision-making and action oriented from biosafety. The prevention of illnesses and accidents prevails over any feature of participation, defining governance by its self-care. In this way, the conflict between universities and public administration advances towards a multilateral and inclusive agreement. This feature of governance that begins with the internal dialogue of the parties to the extent of the agreements between rival actors distinguishes it from other proposals. Before the government of common goods and corporate government, governance stands out as an open agenda for change, repository of proposals and regulator of differences. In the face of a global crisis such as the pandemic, governance is seen as a turning point for humanity. Unlike democracies where the inclusion of all is assumed by a principle of diversity and equity, governance is for those who participate until they reach the status of contributors to a global problem. It is not about a participation embodied by followers, militants and adherents to a political ideology, charismatic leader or interpretation of the basic needs and expectations of the agents. It is a contribution between the parties that have the potential to discuss the issues on the public agenda. Governance is a construction of those who manifest themselves both in the streets and in the media. Dissidents of a regime that presumes to be democratic. Critics of an apparently inclusive and democratic system. Talent Development Contributors. Facilitators of intangible assets in knowledge-creating organizations.

Acknowledgment

None.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest.

References

- World Health Organization (2022) Statistic for coronavirus SARS CoV-2 and COVID-19 disease in the world. Gynevra: WHO.

- Panamerican Health Organizaton (2022) Statistic for coronavurus SARS CoV-2 and COVID-19 diseasein the Amerias. New York: PAHO.

- Organization for Economic and Cooperativ Development (2022) Statistic for coronavirus SARS CoV-2 and OVID-19 disease in countrie. Gynevra: OECD.

- Bishop MG (2007) A picture of dentistry at charing cross in the 1730s given by Hogarths painting and print of night. Professional governance identity and possible mercury intoxication as an occupational hazard for his barber tooth drawer. British dental Journal 203(5): 265-269.

- Schleicher J, Peres C, Amano T, Llactayo W, Williams N (2017) Conservation performance of different conservation governance regimes in the periurban Amazon. Scientific Reports 7: 11318.

- Vasconcelos V, Hannan PM, Levin SA, Pacheco JM (2020) Coalition structure governance improves cooperation to provide public goods. Scientific Reports 10: 9194.

- Wang H, Li B (2021) Environmental regulations, capacity utilization and high-quality development in manufacturing: An analysis based on Chinese provincial panel data. Scientific Report 11: 19566.

- Azhar M, Aulia H (2020) Government strategy in implementing the good governance during covid-19 pandemic in Indonesia. Administrative Law & Governance Journal 3(2): 240-254.

- Jowitt SM, Mudd GM, Thompson JF (2020) Future availability of nonrenewable metal resources and the influence of environmental, social and governance conflicts of metal production. Health & Environmental Communications 1: 13.

- Unger C, Mar KA, Gurtier K (2020) A club's contribution to global climate governance: the case of the climate and clean air coalition. 6: 99.

- Oancea A (2019) Research governance and the futures(s) of research assessment. Palgrave Communications 5: 27.

- Rajan D, Koch K, Rohrer K, Bajnozki C, Socha A, et al. (2020) Governance of the Covid-19 response: A call for more inclusive and transparent decision making. Global Health 5: e002655.

- Cordova E (2020) Governance and life project rethinking post-pandemic society. Latin American Utopia and Praxis 25(8): 14-29.

- Gille F, Veyena E, Blasimme A (2020) Future proofing bio banks governance. European Journal of Genetics 28: 989-996.

- Plagiarism E (2021) The Swedish initiative and the 1972 Stockholm conference: The decisive role of science diplomacy in the emergence of global environmental governance. Humanities & Social Science Communications, 82.

- Beaton A, Hudson M, Milne M, Viola R, Russell K, et al. (2017) Engaging Maori in biobanking and genomic research: A model for biobanks to guide culturally informed governance, operational and community engagement activities. Genetics in Medicine 19(3): 345-351.

- Angelov M, Kaschel T (2017) Toward quantifying soft power: The impact of the proliferation of information technology on governance in the middle east. Palgrave Communications.

- Langlois A (2017) The global governance of human cloning: The case of UNESCO. Palgrave Communications 3: 17019.

- May C (2015) Who's in charge? Corporations and institutions of global governance. Palgrave Communications 10: 1057.

- Shaw TM (2015) From post BRICS decade to post 2015: Insight for global governance and comparative regionalism. Palgrave Communications 10: 1057.

- Haward M (2018) Plastic pollution of the world’s seas and ocean as a contemporary challenge in ocean governance. Nature Communication 9: 667.

- Shah N, Coathup V, Teare H, Forgie I, Giordano JN, et al. (2019) Sharing data for future research engaging participants in views about data governance beyond the original project: A direct study. Genetics in Medicine 21(5): 1131-1138.

- Conejero E, Segura MC (2020) Global governance and the objectives of sustainable development in Spain. Research and Critical Thinking 149-169.

- Harris R, Burnside G, Ashcroft A, Grievenson E (2009) Job satisfaction of dental practitioners before and after change in incentives and governance: A longitudinal study. British Dental Journal 207: E4.

- Holden LC, Moore RS (2004) The development of a model and implementation process for clinical governance in primary dental care. British Dental Journal 196(1): 21-25.

- McCormick RJ, Langford JW (2016) Attitudes and opinions of NHS general dental practitioners towards clinical governance. British Dental Journal 200: 214-217.

- Sleigh J, Wayena E (2021) Public engagement with health data governance: The role of visuality. Humanities & Social Science Communications 8: 149.

- Nabin MH, Tarequi M, Battacharday S (2021) It matters to be in good hands: The relationships between good governance and pandemic spread inferred from cross country Covid-19 data. Humanities and Social Science Communications 8: 113.

- Lubell M, Morrison TH (2021) Institutional navigation for polycentric sustainability governance. Nature Sustainability 4: 664-671.

- Fan PF, Yang L, Li, Y, Ming T (2020) Build of conservation research capacity in China for biodiversity governance. Nature Ecology & Evolution 4: 1162-1167.

- Ullah A, Pinglu S, Ullah S, Abbas H, Khan S (2020) The role of e-Governance in combating Covid-19 and promoting sustainable development. A comparative study in China and Pakistan. Chinese Political Science Review 6: 1-33.

- Milano S, Mittelstadt B, Wacher S, Russell C (2021) Epistemic fragmentation poses a threat to the governance of online targeting. Nature Machine Intelligence 3: 466-472.

- Hassan I, Mukaiwagara M, King L, Fernandez G, Sridhar D (2021) Hindsight is 2020? Lessons in global health governance one year into the pandemic. Nature Medicine 27: 396-400.

- Brodie T, Rukeishaus M, Swilling M, Allison EH, Osterblom H, et al. (2020) A transition to sustainable ocean governance. Nature Communication 11: 36000.

- Luisetti T, Ferrini S, Grilli G, Jickkells TD, Kennedy H, et al. (2020) Climate actions require new accounting guidance and governance frameworks to manage carbon in shelf seas. Nature Communication 11: 4599.

- Liu Y, Zhou Y, Lu J (2020) Exploring the relationship between air pollution and meteorological conditions in China under environmental governance. Scientific Reports 10: 14518.

-

Javier Carreón Guillén, Cruz Garcia Lirios*, Francisco Espinoza Morales and Gilberto Bermudez Ruíz. Academic Governance Networks in the COVID-19 Era. Arch of Repr Med.. Med. 1(3): 2023. ARM.MS.ID.000512.

-

Covid-19, Governance, Social representations, Educational policy, Pandemic, Agenda, Sick

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.