Research Article

Research Article

Rheumatic Diseases in Aged Homeless in US

and Canada

Amy Hicks1*, Minor J1, Chetta M1, Kadio B1,2, Yaya S2, Basak A3, Coulibaly A4 and Nezi E5

1Center for Community and Global Health (CCGH), Bob Jones University, USA

2School of International Development and Globalization, University of Ottawa, Canada

3Center of Chronic Diseases, University of Ottawa, Canada

4Department of Public Health, Felix Houphouet Boigny University, Côte d’Ivoire

5National Institute of Public Health, Côte d’Ivoire

Amy Hicks1*, Minor J1, Chetta M1, Kadio B1,2, Yaya S2, Basak A3, Coulibaly A4 and Nezi E5

1Center for Community and Global Health (CCGH), Bob Jones University, USA

2School of International Development and Globalization, University of Ottawa, Canada

3Center of Chronic Diseases, University of Ottawa, Canada

4Department of Public Health, Felix Houphouet Boigny University, Côte d’Ivoire

5National Institute of Public Health, Côte d’Ivoire

Amy Hicks, School of Health Professions, Bob Jones University, USA.

Received Date: July 05, 2020; Published Date: July 30, 2020

Abstract

This exploratory paper provides an overview of rheumatic diseases (RD) in aged homeless populations in the US and Canada. We analyzed general data on the subject from articles retrieved online. Relatively few studies have focused on this question over the recent years. Our findings indicate that individuals facing housing instability age faster than the general North American population by a difference of 10 to 20 years. This premature aging leads to the occurrence of RDs at a significantly younger age. Arthritis was the most commonly reported condition. Although prevalence was similar as in in the general population, arthritic homeless individuals were 22 years younger in average and more often exhibited a polyarticular clinical presentation. Co-morbidity involving both communicable and non-communicable diseases was constant. Connective tissue disorders such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA) remain common with sometimes a florid symptomatology no more seen in the general population. Finally, the more compounding effects of RD associated with aged homelessness were severe chronic pain and ankylosis, which also resulted in a higher frequency of falls. We hypothesize that the close interactions between rheumatic diseases, chronic pain and falls created a singular pathway to premature death, even years after individuals exit from homelessness. Further multidisciplinary research is needed to explore the ways specific public health programs can be developed to address the needs of this particularly vulnerable population.

Introduction

diseases (RDs) in aged individuals facing housing instability has been generally overlooked [1]. Most homeless research in the recent years have mainly focused on substance abuse and mental health and the population of interest for public health interventions are generally directed towards the youths and the young adults [2]. However, available data suggest that individuals facing multiple social burdens, termed intersectional vulnerability, have worse health outcomes when compared to the at-risk population. We argue that a lack of more targeted studies on aged homeless might contribute to the invisibility surrounding this particular sub-population. Thus, the goal of this study is to generate knowledge and increase awareness on the health of individuals living at the intersection of aging and homelessness. More specifically, the research intents to explore demographic data, clinical patterns, and outcomes of rheumatic disorders in the North American homeless population. We also analyze what model could derive from the interaction to explain increased mortality in aged homeless in US and Canada. Findings for this work will shed a new light into the pathways to premature death and provide ground for a renewed interest in health disparities in line with the Healthy People 2020 Agenda [3].

Method

This work uses a secondary data analysis design. Relevant articles were retrieved from different online databases and were screened for both qualitative and quantitative data on age, homelessness, and rheumatic disorders

Search strategy

We used both an electronic and a manual search. A first line of search was conducted on PubMed using the Boolean operators « AND » and « OR » with the different MESHs: « Homeless person » and a series of different rheumatic diseases selected based on their prevalence in the general US and Canadian populations. Hence, the following MESHs were used: « arthritis »; « osteoarthritis »; « gout »; « lupus »; « spondylarthritis ». We also included « chronic pain » as a search term as most RD include pain in their clinical symptoms. A second line of search was conducted on the Web of Science database using the same method. Then a manual search followed using a snowballing technique earlier described by Claes. The technique consists in screening the references of articles retrieved electronically for relevant publications until a point of saturation is reached, where new articles are not found [4].

Inclusion criteria

Abstracts of the articles were screened for eligibility. To be included in the analysis, extracted data should satisfy a PICO framework Schardt C, et al. [5], where the study population (P) included at least older homeless individuals; the Intervention (I) was any type of clinical or public health program targeting rheumatologic disorders; the Comparison (C), was a pre or post intervention analysis within the aged homeless population or with other populations; finally, the Outcomes (O) should include the results of the intervention and their impact on homelessness. While our study population was the aged homeless in the United States and Canada, studies conducted elsewhere were included but for the discussion portion of the research. Articles were not tested for quality, and no publication date restriction was imposed.

Results

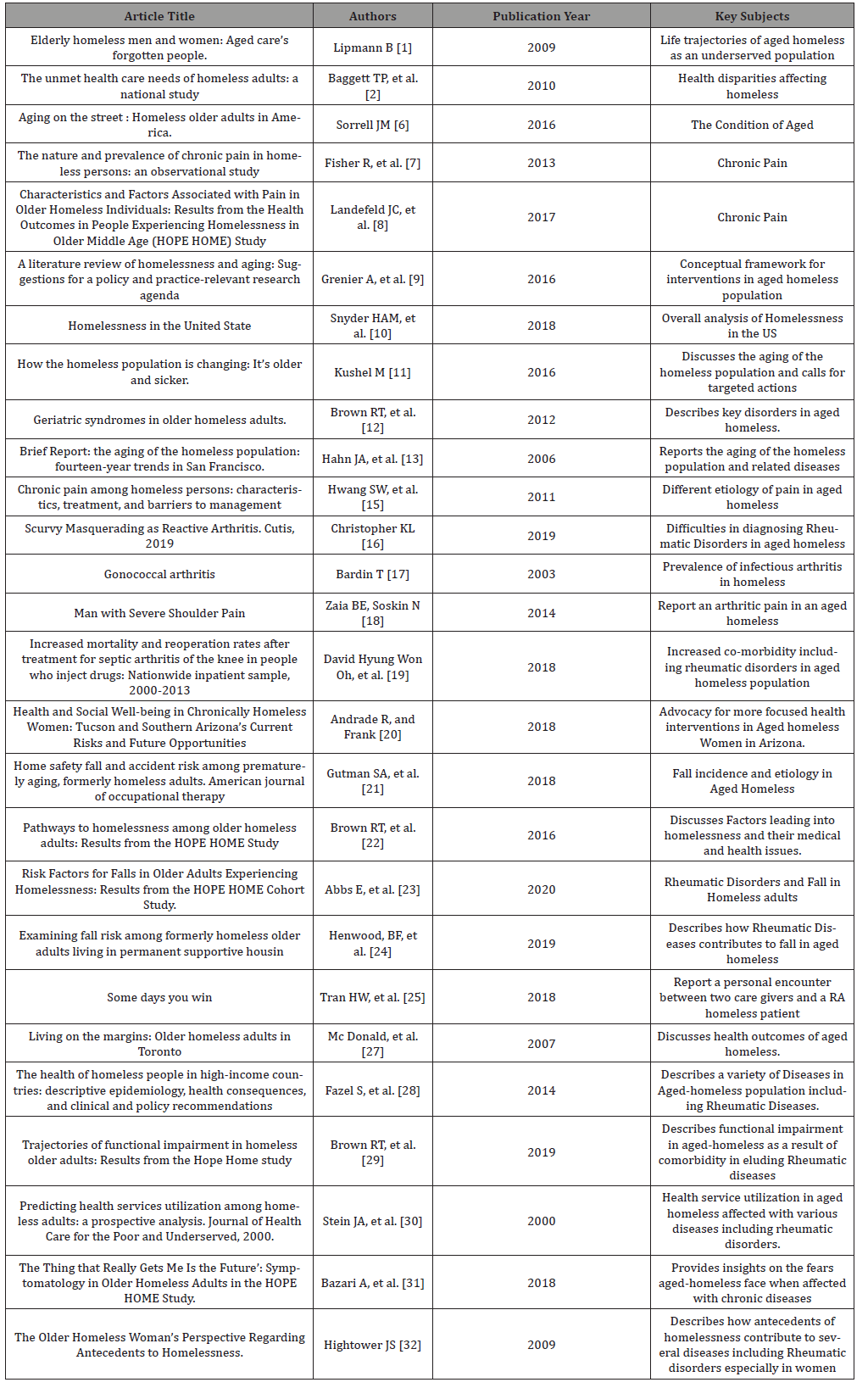

Table 1:Description of Articles included in this review.

Descriptive Data of the Aged Homeless in The US

Definition of aged homeless

If aged homelessness appears intuitively understandable, the practical definition of the concept is much more nuanced. A first complicating factor of the definition is the distinction that should be made on the trajectory of aged individuals onto homelessness. Two distinct trajectories are described: the first group includes individuals who have been without secure housing and have been living in shelters or on the streets for a significant time and are now at a certain age. The second group instead designs individuals who experience homelessness for the first time when they are at an advanced age [6]. That trajectorial distinction is important from an interventional standpoint since it represents a different social dynamic with similarly different health outcomes. Another element adding to a definitional complexity comes from the notion of age itself. Indeed, it is difficult to set the precise definition of advanced age when dealing with a population whose life expectancy is somewhere between 42 and 52 [7]. The homeless population experiences an earlier onset of age-related disorders, compared to the general population [8]. Thus, the age threshold varies according to authors: Grenier and colleagues establish it to be 50-rather than the standard 65-and see it as most appropriate marker of old age in a homeless population [9]. But there’s a general consensus among researchers that the physical age of the homeless to be about 10 to 20 years below their chronological age [6].

Demographics

According to the 2018 Annual Homeless Assessment Report (AHAR), the Point-In-Time (PIT) count in January, 2018 determined 552,830 people to be experiencing homelessness in the United States, making it the largest homeless population in Western countries with an estimated number of over 3 million in the course of the year [10]. At the national level, ethnoracial distribution of the aged homeless population reflects significant disparities in risk. In both sheltered and unsheltered homeless, Caucasian Americans represent 47%, followed by African Americans at 40%, as per a 2019 PIT Report from the HUD (https://files.hudexchange.info/ reports/published/CoC_PopSub_NatlTerrDC_2019.pdf). There was also a strong male predominance with 60% males versus 38% females, and less than 1% for transgenders. Additionally, US service Veterans compose approximately 6% of the homeless population. However, one factor that stood out from the different studies is the new age distribution in that group. Indeed, the aging of the homeless population follows the general trend of the of the US population, only at an accelerated pace. In the 1990s, only 11% of the homeless population was 50 years of age or older [11]. A decade, later, that proportion rose to 30% [12] and is now believed to be at 50% [13]. In Canada, the 2014 PIT Report was estimated at 35 000. It’s also estimated that between 13 to 33 000 people are affected by chronic homelessness [14]. If the increase in the homeless population is relatively slower when compared to the US trend, it is nonetheless concerning [14]. That rapid increase in the aged homeless population in both the US and Canada poses new challenges for health interventions and reflects a shift in their health needs.

Rheumatic Diseases in Aged Homeless

Arthritis

The American College of Rheumatology (ACR) defines arthritis as an inflammatory process affecting the osteoarticular system. It encompasses a broad category of diverse diseases from different etiological patterns which all affect the skeleto-muscular system, either primarily or secondarily, on a chronic, sub-chronic or acute basis. In 2011, a cross-sectional study was conducted in the Boston, MA area which aimed to establish the prevalence of geriatric syndromes in older homeless adults. The study included two hundred and forty-seven homeless adults aged 50–69 recruited from eight homeless shelters. The study compared the prevalence of geriatric syndromes in older homeless adults to findings of the prevalence of these syndromes in the general elderly adult population. Studies included data from the MOBILIZE Boston Study (MBS), the National Health And Nutrition Examination Study (NHANES) and the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS). The prevalence of arthritis in the homeless aged adults was found to be 44.9%. This prevalence was similar to that reported for the general population in MBS (48%, p value=0.31), but the mean age difference of those suffering from arthritis between the two populations was 22 years: (56 (±4.8) Vs (78.1(± 5.4), p value < 0.001). Also, the authors found that arthritis was more prevalent in the homeless population than in national averages: 44.9% vs 35%, p value <0.001 for NHANES, and 44.9% vs 38.6%, p value <0.04 for NHIS. The authors also reported that arthritis presented more often as part of a comorbid condition with asthma or COPD and depression in aged homeless more than in the reference populations of the study (p value <0.001). As a consequence, activities of daily living (ADL), instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) and mobility were significantly impaired in the study group when compared to the MBS (resp. 30 Vs 22 (p value = 0.004) [12]. Similar findings are reported by Gutman and coworkers in their exploratory research in New York [14]. The study consisted in home safety visits of formerly homeless adults, aged between 40–64 yr, who were, at the time of the study, residing in supportive housing. Arthritis was the second most common condition reported by the surveyed group (52%), second only to coronary artery disease (60%). The prevalence of arthritis was equal to that of diabetes (52%) and higher than high cholesterol (44%) and hypertension (44%). That, homelessness is an important contributing factor to arthritis development is also corroborated by Jutkowitz et al. in a study focusing on veterans admitted in a community nursing home with a prior history of homelessness [15]. The authors reported that former homeless veterans that were admitted in the facility were slightly more at risk of developing rheumatic diseases then their stable housed counterparts with an adjusted relative risk of 1.1 (CI: 98%) when compared to their stably housed counterparts.

Clinical presentations

Another aspect that has been investigated is the clinical presentation of arthritis in the aged homeless subpopulation. Chronic pain in general and in particular chronic articular pain are constant companions of aged homelessness. A Canadian study by Hwang and collaborators investigated chronic pain in the aged homeless using a cross-sectional design based on the Chronic Pain Grade questionnaire. It was established that the age at the onset of pain was as early as in the 30’s, but the pain localization involved almost all the articulation of the body with a significantly higher frequency for the knees (36.4%) and an equal frequency for the back and shoulders (18.2%). Grade IV pain was also common especially for the back (63%). It should be noted that injuries along with arthritis were the principal causes of that chronic pain [15]. Data from the UK provide further support to Hwang findings. Fisher et al. evaluated chronic pain in UK aged homeless half a decade ago. The lower limbs were the most common site of pain (51.4%), and polyarticular involvement was common (27.9%). In the US, a recent study (2017) in California by Landefeld et al. based on interviews of 350 homeless individuals aged 50 and older concluded that almost half of the study group (44.3%) experienced chronic pain from arthritis, varying from moderate to severe. Like the Canadian and UK findings, the author reported the prematurity of the symptoms as some participants reported pain dating back 10 years. In addition to the premature, polyarticular onset of pain typical to arthritis in aged homeless, another particularity resides in the misleading clinical form that arthritis takes in this vulnerable, comorbid population. Kristopher, Menachof and Fathi report a case of scurvy in an adult homeless mimicking a reactive arthritis [16]. Prevalent also in this debilitated population are secondary articular localizations of infectious diseases such as hepatitis C or TB. Gonococcal and other forms of septic arthritis are regularly reported in the homeless population in general [17-19].

Falls

With arthritis, falls form a vicious cycle in aged homeless. As reported by a study in aged homeless women, management of arthritic pain and access to quality treatment is very challenging. When individuals are unable to control when and where to rest, elevate affected limbs, apply heat/cold or access specialist treatment or physical therapy, control of the diagnosed condition is very difficult [20]. Thus, the poor management of arthritic pain exposes that subpopulation to an increased risk of falls when compared to their stable housed counterparts. This, in turn, significantly increases the risk of ankylosing spondylitis which further deepens the rheumatic symptomatology [21]. A very recent study by Abbs and coworkers as part of the Health Outcomes in People Experiencing Homelessness in Older Middle agE (HOPE HOME) project, investigated risk factors of falls in aged homeless. Study design consisted in a longitudinal multiethnic cohort of 350 aged homeless with participant interviews every 6 months for 3 years in Oakland, California [22, 23]. Adjusted odd ratios (AOR) was estimated for specific risk factors. It was demonstrated that falls were more frequent in aged homeless when compared to the general population with increasing risk with age and for women (AOR=1.45 (1.02-2.04, CI 95%)). Whites were at higher risk (AOR: 1.65 (1.12–2.43), CI 95%) than African Americans. Arthritis was also identified as a risk factor for falls along with pain, social and physical environment, and physical assault in the previous 6 months [23]. Another recent study investigated the adequacy of the Permanent Supportive Housing (PSH) system for aged homeless in regard to the increased risk of falls in that population. They also researched the risk factors of falls in aged adults with prior experience of homelessness. Interestingly, the authors found that although PSH has been credited with the decline in homelessness in the US since 2007, tenants have a high prevalence of falls and serious fall-related injuries. This risk was correlated with lifetime years of homelessness. Additional risk included functional impairment, frailty, and persistent pain [24].

Connective tissue disorders (CTDs)

The literature on CTDs in older homeless populations is scarce and hard to find. Reasons accounting for such a scarcity relate to the nature of CTDs as a complex and polymorphic group of diseases difficult to diagnose and even much more arduous to investigate in a public health setting and in the context of homelessness. Nonetheless, the white paper referenced earlier and focusing on aged homeless women acknowledges that CTDs such as lupus are not rare in that population [20]. Tran and Panush from Los Angeles County General Hospital/Medical Center reported on a case of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) in an African American aged homeless patient two years ago. The authors provided a description of the case, outlining the physical, mental, and social suffering of the patient sitting uncomfortably in a wheelchair, grimacing, with a floridly active RA. While it is well established that patients diagnosed and treated early respond well to treatment, for an aged homeless patient diagnosed at an average of 6 years younger and living in the street, the outcomes of RA or even CTDs in general are significantly different and the progression of disease can be irreversible as acknowledged by the authors [25].

Psycho-social Interactions With the Care Personnel

Management of rheumatic disorders more often requires a prolonged follow up of patients. This creates a relationship between the care provider and the patients or with his family. In their study on doctor-patient relationship with regards to rheumatic diseases, Haugly, Strand and Finset interviewed two groups of patients: one with a well-defined inflammatory condition (rheumatoid arthritis (RA) or ankylosing spondylitis) and one with non-inflammatory widespread chronic pain such as fibromyalgia. The investigators reported that both groups saw as of central importance “to be seen” and “to be believed” [26]. The authors explain the concept of visibility or “to be seen” as an expression of positive affirmation of the patient as a human being. The credibility concept, “to be believed”, relates to pain and suffering including all those subjective symptoms that the care provider cannot feel or evidence yet experienced by the patient. When the rheumatic patient is one that is at the intersection of old age, ethnicity, and homelessness, those two concepts of visibility and credibility resonate in a very particular manner. In the case reported by Tran and Panush discussed earlier, the authors share how they felt during the first encounter with that elderly African American homeless female patient suffering with RA. The psycho-social interaction between aged homeless affected with RD and their care providers is fraught with complications. These interactions come with the frustration of seeing a patient in great suffering and needing on-going care but knowing that he or she is at great risk of being lost to follow-up [25]. At the same time, the prevalence of co-morbidities in older homeless persons including mental health issues requires a tactful approach by the healthcare providers [27]. Stigma of homelessness and mental health problems can be a barrier to effective communication between patients and providers.

Management of Rheumatic Diseases in Aged Homeless

The management of RD in aged homeless patients often lacks coherent evidence-based practice and policies. Findings from multiple studies in high income countries reveal that although the homeless population has increased utilization of the ER, in general, there are no specific protocols for discharge and follow-up treatment. This lack of standardization in seen in community health interventions as well as in medical care for aged homeless affected with RD [28]. This is corroborated by the uncertainty raised by the authors of the RA case report as to the possibility of conducting an appropriate follow up of RA in a patient with no fixed domicile and living in unpredictable conditions [25]. Lack of specific programs or medical approach constitutes one of the key factors furthering the functional impairment in aged homeless individuals as reported by Brown and coworkers [29].

Discussion

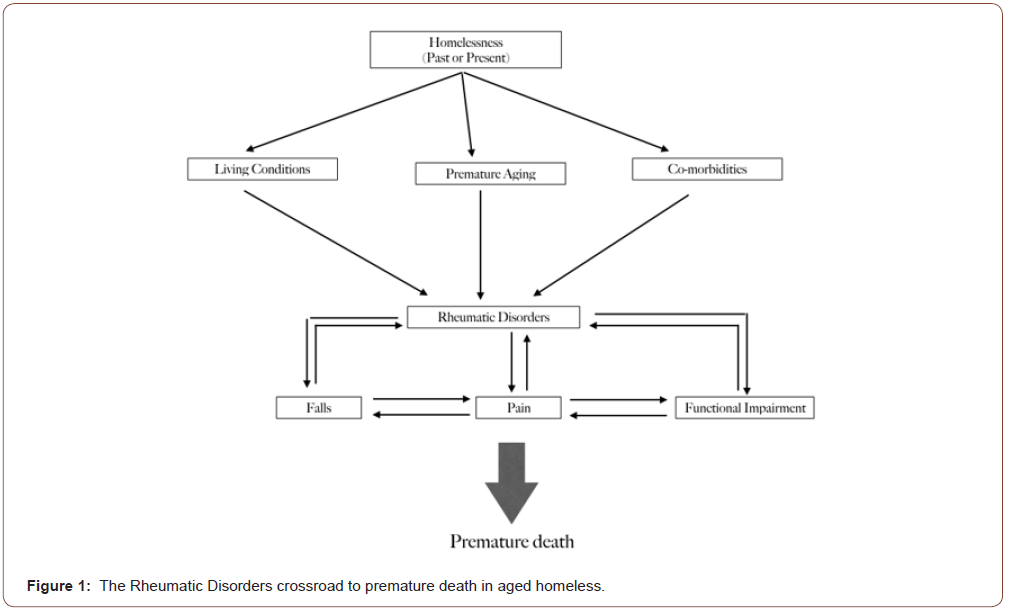

Most health interventions and programs in homeless over the recent decades could be classified into three major categories: mental health, substance abuse and addiction, and infectious diseases [30]. If such a triple-focus is amply justified, given their relative prevalence, it appears that there is an insidious condition that is being overlooked. The necessity of focusing on RD in the homeless population is generally unrecognized. In a context where co-morbidity is common, it is necessary from a policy standpoint to clearly identify interventional priorities to maximize health gains [9]. It appears that, given their multifactorial nature, RD greatly increase the suffering of homeless populations when they reach a certain age. One study conducted in the aged homeless population in California illustrated that becoming unable to perform ADL is a significant fear for this population [31]. Figure 1 depicts the vicious cycle that deepens and compromises the pathway out of homelessness. Patients remain at risk, even years after ending homelessness [24]. In other words, the cumulative long-term effects of homelessness in RD is a sequence that may be irreversible. That deterministic nature of homelessness on health in general has been described by former homeless women [32]. The implications for health policy in homeless populations are two-fold: primary prevention of homelessness is always the best avenue given its detrimental nature on health. The second policy option is secondary prevention, but with a focus on high impact diseases which should at least include RD. Some researchers recommend lowering the age of health benefits from 65 to 50 if individuals have a past or present experience of homelessness. Specific rheumatological programs combining access to medical care, falls prevention programs and physical rehabilitation should become standardized protocols for the care of RD in the aged homeless. Future research should focus on how to develop such policies and turn them into actual community health programs (Figure 1).

Conclusion

Exploratory studies have the ability to address emerging issues in a direct, concise, and timely manner [33, 34]. With the aging of the general population in the US and in Canada, new research fields are quickly emerging. The homeless population is also exhibiting a shift in age, manifesting changing health needs. Our analysis aimed at exploring prevalence, clinical presentation, management, and outcomes of RD in aged homeless individuals. It appears that this specific category of diseases, although highly prevalent in individual facing housing instability, is often neglected in health interventions. This quick overview of the body of evidence suggests that RD are part of a morbid cycle contributing to falls, pain and physical impairment and ultimately to premature death in aged homeless. More research should be done in individuals facing intersectional type of vulnerability, here age and homelessness to inform both population health action.

Acknowledgement

None.

Conflicts of Interest

No conflict of interest.

References

- Lipmann B (2009) Elderly homeless men and women: Aged care's forgotten people. Australian Social Work 62(2): 272-286.

- Baggett TP, James JO Connell, Daniel E Singer, Nancy A Rigotti (2010) The unmet health care needs of homeless adults: a national study. Am J Public Health 100(7): 1326-1333.

- Koh HK, Blakey CR, Roper AY (2014) Healthy People 2020: a report card on the health of the nation. JAMA 311(24): 2475-2476.

- Wohlin C (2014) Guidelines for snowballing in systematic literature studies and a replication in software engineering. EASE '14: Proceedings of the 18th International Conference on Evaluation and Assessment in Software Engineering (38): 1-10.

- Schardt C, Martha B Adams, Thomas Owens, Sheri Keitz, Paul Fontelo (2007) Utilization of the PICO framework to improve searching PubMed for clinical questions. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 7(1): 16.

- Sorrell JM (2016) Aging on the street: Homeless older adults in America. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv 54(9): 25-29.

- Fisher R, Judith Ewing, Alice Garrett, E Katherine Harrison, Kimberly Kt Lwin, et al. (2013) The nature and prevalence of chronic pain in homeless persons: an observational study. F1000Research 2: 164.

- Landefeld JC, Christine Miaskowski, Lina Tieu, Claudia Ponath, Christopher T Lee, et al. (2017) Characteristics and Factors Associated With Pain in Older Homeless Individuals: Results From the Health Outcomes in People Experiencing Homelessness in Older Middle Age (HOPE HOME) Study. J Pain 18(9): 1036-1045.

- Grenier A, Rachel Barken, Tamara Sussman, David Rothwell, Valérie Bourgeois Guérin, et al. (2016) A literature review of homelessness and aging: Suggestions for a policy and practice-relevant research agenda. Can J Aging 35(1): 28-41.

- Snyder HAM, Sheen AM Flynn BMRL Homelessness in the United States.

- Kushel M (2016) How the homeless population is changing: It’s older and sicker. The Conversation.

- Brown RT, Dan K Kiely, Monica Bharel, Susan L Mitchell (2012) Geriatric syndromes in older homeless adults. J Gen Intern Med 27(1): 16-22.

- Hahn JA, Margot B Kushel, David R Bangsberg, Elise Riley, Andrew R Moss (2006) BRIEF REPORT: the aging of the homeless population: fourteen-year trends in San Francisco. J Gen Intern Med 21(7): 775-778.

- Stephen Gaetz, Tanya Gulliver Garcia, Tim Richter T (2014) The state of homelessness in Canada 2014. Canadian Homelessness Research Network.

- Hwang SW, Emma Wilkins, Catharine Chambers, Eileen Estrabillo, Jon Berends, et al. (2011) Chronic pain among homeless persons: characteristics, treatment, and barriers to management. BMC Fam Pract 12(1): 73.

- Christopher KL, Menachof KK, Fathi R (2019) Scurvy Masquerading as Reactive Arthritis. Cutis 103(3): E21-E23.

- Bardin T (2003) Gonococcal arthritis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 17(2): 201-208.

- Zaia BE, Soskin N (2014) Man With Severe Shoulder Pain. Ann Emerg Med 63(5): 528, 571.

- David Hyung Won Oh, Alysse Gail Wurcel, David Joseph Tybor, Deirdre Burke, Mariano E Menendez, et al. (2018) Increased mortality and reoperation rates after treatment for septic arthritis of the knee in people who inject drugs: Nationwide inpatient sample, 2000-2013. Clinical orthopaedics and related research 476(8): 1557-1565.

- Andrade R, Frank F (2018) Health and Social Well-Being In Chronically Homeless Women: Tucson And Southern Arizona’s Current Risks And Future Opportunities.

- Gutman SA, Kevin Amarantos, Jan Berg, Melissa Aponte, Daniela Gordillo, et al. (2018) Home safety fall and accident risk among prematurely aging, formerly homeless adults. Am J Occup Ther 72(4): 7204195030p1-7204195030p9.

- Brown RT, Leah Goodman, David Guzman, Lina Tieu, Claudia Ponath, et al. (2016) Pathways to homelessness among older homeless adults: Results from the HOPE HOME Study. PLoS One 11(5): e0155065.

- Abbs E, Rebecca Brown, David Guzman, Lauren Kaplan, Margot Kushel (2020) Risk Factors for Falls in Older Adults Experiencing Homelessness: Results from the HOPE HOME Cohort Study. J Gen Intern Med 35(6):1813-1820.

- Henwood BF, Harmony Rhoades, John Lahey, Jon Pynoos, Deborah B Pitts, et al. (2019) Examining fall risk among formerly homeless older adults living in permanent supportive housing. Health Soc Care Community 28(3): 842-849.

- Tran HW, Panush RS (2018) Some days you win. Clin Rheumatol 37(9): 2585-2586.

- Liv Haugli, Elin Strand, Arnstein Finset (2004) How do patients with rheumatic disease experience their relationship with their doctors? A qualitative study of experiences of stress and support in the doctor–patient relationship. Patient Educ Couns 52(2): 169-174.

- Mc Donald LJ, Dergal, Cleghorn L (2007) Living on the margins: Older homeless adults in Toronto. J Gerontol Soc Work 49(1-2): 19-46.

- Fazel S, Geddes, Kushel (2014) The health of homeless people in high-income countries: descriptive epidemiology, health consequences, and clinical and policy recommendations. The Lancet 384(9953): 1529-1540.

- Brown RT, David Guzman, Lauren M Kaplan, Claudia Ponath, Christopher T Lee, et al. (2019) Trajectories of functional impairment in homeless older adults: Results from the HOPE HOME study. PLoS One 14(8): e0221020.

- Stein JA, Andersen RM, Koegel P, Gelberg L (2000) Predicting health services utilization among homeless adults: a prospective analysis. J Health Care Poor Underserved 11(2): 212-230.

- Bazari A, Maria Patanwala, Lauren M Kaplan, Colette L Auerswald, Margot B Kushel (2018) 'The Thing that Really Gets Me Is the Future': Symptomatology in Older Homeless Adults in the HOPE HOME Study. J Pain Symptom Manage 56(2): 195-204.

- Hightower JS (2009) The Older Homeless Woman's Perspective Regarding Antecedents to Homelessness.

- Belton RT (1982) Mini-Reviews. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences 4(1): 129-134.

- Donaldson MR, Aday DD, Cooke SJ (2011) A Call for Mini-Reviews: An Effective but Underutilized Method of Synthesizing Knowledge to Inform and Direct Fisheries Management, Policy, and Research. Fisheries 36(3): 123-129.

-

Amy Hicks, Minor J, Chetta M, Kadio B. Rheumatic Diseases in Aged Homeless in US and Canada. Arch Rheum & Arthritis Res. 1(2): 2020. ARAR.MS.ID.000510.

-

Rheumatic diseases, Population, Housing instability, Connective tissue disorders, Rheumatoid arthritis, Aged homelessness, Chronic pain, Premature death

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.