Research Article

Research Article

Evaluating Physical Activity And Quality of Life For Older Adults Through Walk With Ease

Kimberly A Shaffer1*, Heather Hensman Kettrey2, Sarah B King1

1Department of Sport & Exercise Sciences, Clemson University Youth Learning Institute SNAP-Ed, Clemson University, USA

2Department of Sociology, Anthropology and Criminal Justice, Clemson University, USA

Kimberly A Shaffer, Department of Sport & Exercise Sciences, Clemson University Youth Learning Institute SNAP-Ed, Clemson University, USA.

Received Date: September 22, 2021; Published Date: October 01, 2021

Abstract

Background: Prolonged sedentary behavior may have adverse effects on an individual’s physical and psychological well-being, especially among older adult populations. Programs such as Walk With Ease (WWE) have been developed to encourage more physical activity among targeted audiences. However, little research has been done to evaluate the program’s impact on participants’ quality of life in addition to physical activity behavior.

Aims: This study evaluated physical activity and quality of life outcomes among older adults in the WWE program, determined participants with the greatest overall change in behavior, and identified elements within course content that had a significant impact on outcomes.

Methods: Pre- and post-survey assessments (n=86) were administered to participants before and after the six-week program. The assessment included questions from validated tools such as the Physical Activity Scale for the Elderly (PASE) and Brief Inventory of Thriving (BIT) scale. Participant surveys were later matched to provide individual behavior change.

Results: Participants engaged in significantly more walking after completing WWE than they did before beginning the program (g = 0.63; 95% CI [0.33, 0.94]). Attending Session 1 was associated with significant pre-posttest decreases in sitting (b = -2.40, p < .05) and attending Session 3 was associated with significant increases in muscle strength/endurance activities (b = 1.65, p < .01).

Conclusion: WWE provides desirable pre-posttest changes in physical activity and quality of life among a general sample of older adults. A hybrid program in which some activity sessions are provided independently may be a valuable option for future courses.

Keywords: Physical activity, walking, quality of life, Older adults, Health behavior change

Introduction

When public health experts first identified the obesity epidemic in 1999, they issued a call for health professionals to make the development of weight management strategies/programs a public health priority [1]. Despite such efforts to control this epidemic, data from the 2017-2018 wave of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) indicate that the obesity epidemic is growing, with the age-adjusted prevalence of obesity (BMI > 30) among American adults reaching 42% [2].

Although obesity threatens the health of Americans consistently across the life course, prevention efforts often overlook the unique needs of older adults. For example, recommendations from the CDC’s Measures Project tend to target children (e.g., policy recommendations for schools and daycares) or adults as a whole (e.g., policy recommendations for access to healthy foods and safe space for exercise) without much attention to differing needs of younger and older adults. This is a noteworthy oversight, as older adults’ perceived barriers to exercise are often unique from those of younger adults, with one of the most consistent barriers being poor health and/or mobility [3].

Poor health and mobility can lead to sedentary behavior, defined as waking behavior characterized by minimal-energy expenditure while in a resting or reclining position [4]. A systematic review of longitudinal studies indicated that longer durations of sedentary behavior can lead to increased risk of obesity, diabetes, site-specific cancers (e.g., ovarian, colon, endometrial), cardiovascular disease, and mortality [5]. Additionally, a recent meta-analysis indicated that sedentary behavior is inversely related to health-related quality of life, defined as self-perception of quality of life [6]. These patterns have serious implications for older adults, as data from the NHANES indicate older Americans spend approximately 60% of their waking hours engaged in sedentary behavior [7].

Thus, programs that encourage older adults to engage in lowimpact physical activities, such as those that can be performed by individuals with health/mobility concerns, have great potential to prevent the adverse health outcomes of sedentary behavior and promote quality of life. One such program that has shown some empirical evidence of health benefits among older Americans is Walk With Ease (WWE).

Walk With Ease

Walking is a low-impact activity that is inexpensive, safe, convenient, and acceptable for adults with limited mobility. Thus, to promote walking as an accessible form of physical activity, the Arthritis Foundation developed WWE, a 6-week community-based program for adults with low mobility. The overarching goals of WWE are to educate arthritis patients about physical activity/ arthritis management and to provide ongoing opportunities to engage in physical activity [8]. The program follows a 6-chapter manual, with participants completing one chapter during each weekly session [9] (Arthritis Foundation, 2010).

Session 1 introduces participants to the health benefits of walking. Session 2 provides participants with facts about arthritis and exercise, defines moderate activity, provides “dos” and don’ts” of exercise, and discusses exercise safety. During Session 3 participants learn to select the right shoes and socks for walking, develop an exercise plan, select an exercise location, and complete a walking diary. Session 4 addresses barriers to exercise (e.g., pain, discomfort) that participants may experience while implementing their exercise plan. Session 5 provides tips for comfortable walking and teaches participants to measure exercise intensity and personal fitness level. Finally, in Session 6 participants receive resources on how to maintain physical activity.

WWE has accumulated a growing body of research evaluating its health benefits. These studies show promising results, but they tend to be limited in scope in a couple of important ways. First, existing studies largely focus on pain, fatigue, flexibility, and mobility outcomes among older adults living with arthritis [10-13]. To date, there are no studies examining the effects of WWE among general populations of older adults and only one study as evaluated quality of life outcomes. Specifically, Bruno et al. (2006) examined pre- and posttest changes in depression among older adults with arthritis who participated in WWE, but they found no effect on this outcome.

Second, the existing research has either (1) compared the selfguided WWE format to the community-based WWE, (2) compared WWE to another active treatment condition, or (3) compared preand posttest measures among a single group of WWE participants without attention to variation in participant characteristics or in treatment exposure. As a result, there is little evidence to indicate which participants benefit most from WWE and which specific WWE components/sessions are effective at promoting health and quality of life among older adults.

The present study attempts to fill some of these voids in the empirical evidence base for WWE. Its specific purpose is to (1) evaluate physical activity and quality of life outcomes of WWE when implemented with a general sample of older adults and (2) determine which participants benefit most from WWE as well as identify the WWE sessions that have a significant effect on outcomes. The study specifically addresses the following research questions:

• RQ1: Do WWE participants demonstrate changes in quality of life after completing a community-based WWE program?

• RQ2: Are there any differences in changes in physical activity and quality of life among WWE participants based on age, sex, and race?

• RQ3: Which of the six WWE sessions are associated with significant changes in physical activity and quality of life after participating in a community-based WWE program?

Method

The present study is a single-group pre-posttest evaluation of WWE. It uses data from12 senior centers, community centers, and faith-based organizations that implemented WWE throughout Upstate South Carolina in 2019. This program evaluation relies on a pre-existing de-identified dataset of survey measures that were collected by these agencies for routine administrative purposes. Since the study authors could not identify participants in the pre-existing dataset, our institutional review board deemed the research to be exempt from review.

Participants

The funding mechanism that supported implementation of WWE in the 12 centers providing data for the study necessitates that at least half of participants in each WWE class are eligible to receive Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) benefits. However, there are no other criteria for participation in WWE. Participants who attended Session 1 of WWE were asked to complete a pretest survey prior to any discussion of the curriculum, using a unique identifier so that pre- and posttest surveys could be linked. Participants were asked to complete a posttest immediately after completion of the 6-week program. Of the 159 WWE participants who completed the pretest, 95 also completed the posttest, yielding a response rate of 59.75%. In order to draw conclusions about experiences of older adults, we limited the analytic sample to those participants who were 60 years of age or older. This provided an analytic sample of 86 WWE participants. The mean age of the analytic sample was 74.48 (SD = 7.50), with the majority (77.91%) of participants identifying as female, 20.93% identifying as male, and 1.16% not indicating their sex. The analytic sample was 53.49% White, 41.86% African American, 1.16% Native American, 0% Hispanic, and 3.49% (n = 3) race/ethnicity not reported.

Program Implementation

All WWE classes were conducted by trained facilitators who adhered to the WWE manual. Facilitators directed participants in creating exercise goals, discussed the significance of staying physically active, and demonstrated additional stretching exercises to warm-up and cool-down after each group walking exercise. Each of the six sessions typically lasted two hours and began with a review of the previous week’s session. Participants then logged the number of days they walked since the last session and record their thoughts regarding their physical activity experiences thus far. The facilitator then demonstrated 3-5 chair exercises to engage participants and get them moving prior to walking.

Session 1 included a five-minute walk. However, in order to make progress toward the final goal of a thirty-minute walk, each subsequent session entailed participants walking the duration of the previous week’s walk plus an additional five minutes. Facilitators understood that some participants faced more physical limitations than others and, thus, did not force participants. Rather, they encouraged them to do the best that they felt they could do until the time was completed. Chairs, benches, or alternative seating was provided around each walking track for rest, if needed. Facilitators walked and talked with participants while monitoring time. Once the weekly walking exercise was completed, facilitators instructed participants to return to their seats and perform 3-5 cool-down stretches, led a conversation about the session’s activities, and dismissed participants for the week.

Measures

Participants completed pre- and posttest surveys measuring self-reported physical activity and quality of life. Pre- and posttests were identical except that the pretest included demographic items that were not included on the posttest. Physical activity was assessed using the Physical Activity Scale for the Elderly (PASE) and quality of life was measured using the Brief Inventory of Thriving (BIT) scale.

The PASE asks participants to report how often they engaged in specific physical activities over the past 7 days. Physical activities include sitting behaviors (e.g., reading, watching tv, doing handicrafts), walking (e.g., for fun/exercise, walking the dog, walking to work), light sport/recreational activities (e.g., bowling, golf with a cart, shuffleboard, fishing from a boat/pier), moderate sport/recreational activities (e.g., tennis, ballroom dancing, hunting, ice skating, golf without a cart, softball), strenuous sport activities (e.g., jogging, swimming, cycling, aerobic dance, skiing), and exercise to increase muscle strength/endurance (e.g., lifting weights, pushups). Responses are recorded on a 4-point Likert scale (i.e., Never, Seldom/1-2 days, Sometimes/3-4 days, and Often/5-7 days).

The PASE has shown good reliability and validity in measuring physical activity among older adults, as scale items are highly correlated with each other when administered in written format (r = 0.84) and scores correlate with measures of health status and physiologic measures [14,15]. In the present study, we do not calculate PASE scores for analysis. Rather, in order to evaluate pre-posttest changes in specific physical activities, we recoded each of the use each of the aforementioned items onto a numeric scale (1 to 4, with higher values representing greater frequency of the behavior) and examined pre-posttest differences in each as a discrete outcome.

The BIT asks participants to indicate their level of agreement with ten statements that measure quality of life and psychological wellbeing. Examples include “My life has a clear sense of purpose,” “I feel good most of the time,” “What I do in life is valuable and worthwhile,” and “I feel a sense of belonging in my community.” Responses are recorded on a 5-point Likert scale (i.e., Strongly disagree, Disagree, Neither agree nor disagree, Agree, Strongly agree). The BIT has shown good reliability and validity, as scale items are highly correlated with each other (alpha coefficients are over .90 across samples) and scores correlate with other existing measures of wellbeing [16]. In the present study, we calculated BIT scores by recoding the items onto a numeric scale (1 to 5, with higher values representing greater agreement with the item), summing all items, and dividing the total by 10. We examined preposttest score differences as the outcome of interest. The alpha for the BIT in present study was .93 for both the pretest and posttest.

Data Analysis

We conducted all data analysis in R 3.5.0 [17]. Rates of missing data for the analytic sample were low, ranging from 0% to 6.98% for each variable. Thus, we did not impute missing values and, instead, used pairwise deletion. As a result, the observed sample sizes vary between analyses.

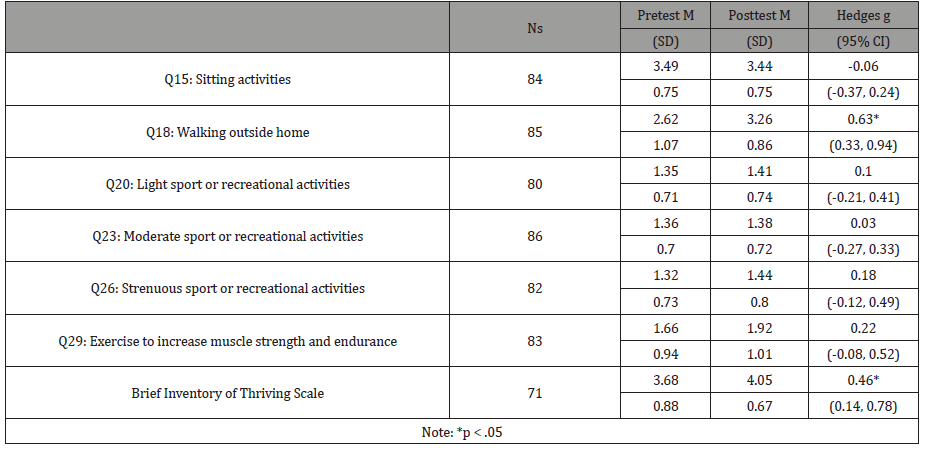

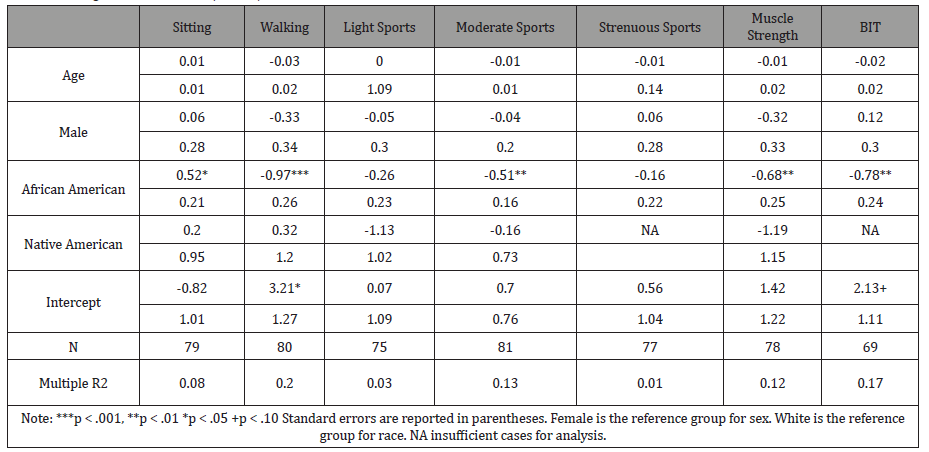

To determine the magnitude and significance of pre-posttest changes in physical activity and quality of life, we calculated standardized mean difference scores with a small sample correction (Hedges g). We report these with their 95% confidence intervals. Then, to determine whether these pre-posttest changes varied significantly based on age, sex, and race/ethnicity of participants, we ran a series of multivariate OLS regression models in which we regressed these demographic variables, net of each other, on preposttest changes in each of the main outcomes. Finally, to evaluate the significance of each WWE session on pre-posttest changes in physical activity and quality of life, we ran a series of multivariate OLS regression models in which we regressed attendance for each of the six sessions (0 = No; 1 = Yes), net of each other, on preposttest changes in the main outcomes. This specific analysis was limited to data provided by the three sites that reported attendance for participants (n = 38).

Results

RQ1: Research Question 1 asked whether WWE participants exhibit pre-posttest changes in measures quality of life. Findings pertinent to these to questions are reported in Table 1, which summarizes Hedges g statistics and corresponding 95% confidence intervals for pre-posttest differences in each of the physical activity outcomes and BIT scores. Results indicate participants’ BIT scores were approximately half a standard deviation higher at posttest than they were at pretest (g = 0.46, 95% CI [0.14, 0.78]). Pre-posttest effects were non-significant for sitting and engaging in light sport/recreational activities, moderate sport/recreational activities, strenuous sport/recreational activities, and exercise to increase muscle strength/endurance.

Table 1:Pre-Posttest Effect Sizes for Physical Activity and Brief Inventory of Thriving Outcomes (N = 86).

RQ2: Research Question 2 asked whether there are any differences in changes in physical activity and quality of life among WWE participants based on age, sex, and race. Table 2 summarizes results from multivariate OLS regression models predicting preposttest changes in physical activity outcomes and BIT from these demographic variables. Findings indicate that the only significant demographic predictor of pre-posttest outcomes was whether or not a participant identified as African American. Compared to White participants, African American participants exhibited larger pre-posttest increases in sitting activities and smaller increases in walking, moderate sport/recreation, and muscle strengthening/ endurance activities. Additionally, compared to White participants, African American participants exhibited significantly smaller increases in BIT scores. Age, sex, and identifying as Native American were not significant predictors of pre-posttest physical activity and BIT outcomes.

Table 2:Unstandardized coefficients from OLS Models Predicting Pre-Posttest Differences in Physical Activity and Brief Inventory of Thriving Outcomes from Age, Sex, and Race (N = 86).

RQ3: Research Question 4 asked which of the six WWE sessions are associated with significant changes in physical activity and quality of life after participating in a community-based WWE program. This specific analysis was limited to data obtained from the three WWE sites that reported attendance data (n = 38). Table 3 summarizes results from multivariate OLS regression models predicting pre-posttest changes in physical activity outcomes and BIT scores from attendance of Sessions 1 through 5. There was no variation in attendance of Session 6 (all participants attended this session); thus, it was dropped from the analysis. Findings indicate that attending Session 1 was associated with significant pre-posttest decreases in sitting (b = -2.40, p < .05) and attending Session 3 was associated with significant increases in muscle strength/endurance activities (b = 1.65, p < .01). Attending Sessions 2, 4, and 5 was not significantly associated with pre-posttest changes in any of the outcomes.

Table 3:Unstandardized coefficients from OLS Models Predicting Pre-Posttest Differences in Physical Activity and Brief Inventory of Thriving Outcomes from WWE Session Attendance (N = 38).

Conclusion

In the present study we sought to evaluate pre-posttest changes in quality of life among a sample of older adults participating in WWE. We also sought to identify any differences in pre-posttest changes based on age, sex, and race of participants as well as determine which program sessions are significant predictors of outcome changes. Findings indicate that older adults who participate in WWE demonstrate increases in quality of life (measured with the Brief Inventor of Thriving) relative to measures reported before participating in the program.

Perhaps one of the most important findings of this study is that African American participants experienced significantly fewer preposttest improvements compared to White participants. This has practical implications, considering that African American adults are at greater risk of obesity than White adults [18]. Thus, the program has fewer benefits for those who may need it most. Future research should seek to determine the source of this disparity by evaluating the influence of racial composition of WWE groups, racial match between facilitators and participants, and culturally-specific program content in predicting disparities in program effects among participants.

In terms of identifying program sessions with the greatest influence on pre-posttest changes in outcomes, our findings indicate that, net of the influence of all sessions as a whole, attending Session 1 is associated with greater pre-posttest decreases in sedentary behavior (i.e., sitting) and attending Session 3 is associated with greater pre-posttest increases in muscle strength/endurance activities. Session 1 serves as an introduction to WWE and emphasizes the benefits of walking; thus, it is intuitive that attending this session may encourage participants to become active and engage in fewer sedentary behaviors. Interestingly, past studies have sought to determine whether community-based or selfdirected versions of WWE have the most benefits [11]. However, the fact that we only found attendance of two program sessions to be significant predictors of outcomes suggest a hybrid version in which participants attend Session 1 and then complete some or all of the remaining sessions independently, may be sufficient for fostering desirable change. Future research should examine this possibility under better controlled conditions, by randomizing participants to a hybrid or full community-based version of WWE. Allowing participants to complete parts of the program independently seems consistent with the logic that walking is an easily accessible physical activity (e.g., no need for special equipment or access to fitness spaces).

Overall, this study makes a couple important contributions to the empirical evidence base for WWE. First, it demonstrates desirable pre-posttest changes in quality of life among a general sample of older adults. Past research has tended to focus on pain, fatigue, flexibility, and mobility outcomes among older adults living with arthritis. A notable dearth of studies has focused on psychosocial wellbeing outcomes and/or more general samples of older adults. Second, this study adds to the extant literature by identifying racial disparities in program outcomes that should be addressed in order for all participants to receive optimal benefit from participating in WWE.

Despite these contributions, findings of this study must be interpreted within the confines of a couple important limitations. First, this study relied on a pre-existing dataset of pre-posttest measures collected from adults who participated in WWE. Thus, there was no control or comparison group. Additionally, the study sample exhibited a high level of attrition, as approximately 40% of participants failed to complete the posttest, potentially introducing bias into the results. These issues mostly result from the fact that this study was an analysis of pre-existing data that were not collected for research purposes.

Conflict of Interest

None.

Acknowledgements

None.

References

- Mokdad AH, Serdula MK, Dietz WH, Bowman BA, Marks JS, et al. (1999) The spread of the obesity epidemic in the United States, 1991-1998. Journal of the American Medical Association. 282(16): 1519-1522.

- Hales CM, Carroll MD, Fryar CD, Ogden CL (2020) Prevalence of obesity among adults: United States, 2017-2018. NCHS Data Brief 360: 1-7.

- Schutzer KA, Graves BS (2004) Barriers and motivations to exercise in older adults. Preventive Medicine 39(5): 1056-1061.

- Tremblay MS, Aubert S, Barnes JD, Saunders TJ, Carson V, et al. (2017) Sedentary behavior research network (SBRN): Terminology Consensus Project process and outcome. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity 14: 75.

- Thorp AA, Owen N, Neuhaus M, Dunstan DW (2011) Sedentary behaviors and subsequent health outcomes in adults: A systematic review of longitudinal studies, 1996-2011. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 41(2): 207-215.

- Boberska M, Szczuka Z, Kruk M, Knoll N, Keller J, et al. (2018) Sedentary behaviours and health-related quality of life: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Health Psychology Review 12(2): 195-210.

- Matthews CE, Chen KY, Freedson PS, Buchowski MS, Beech BM, et al. (2008) Amount of time spent in sedentary behaviors in the United States, 2003-2004. American Journal of Epidemiology 167(7): 875-881.

- Rizzo TH (1999) Walk With Ease: The Arthritis Foundation walking program leader’s guide. Arthritis Foundation.

- Arthritis Foundation (2010) Walk With Ease: Your guide to walking for better health, improved fitness, and less pain. (3rd ed.). Arthritis Foundation.

- Bruno M, Cummins S, Gaudiano L, Stoos J, Blanpied P (2016) Effectiveness of two Arthritis Foundation programs: Walk With Ease and, YOU Can Break the Pain Cycle. Clinical Interventions in Aging 1(3): 295-306.

- Callahan LF, Shreffler JH, Altpeter M, Schoster B, Hootman J, et al. (2011) Evaluation of group and self-directed formats of the Arthritis Foundation’s Walk With Ease program. Arthritis Care & Research 63(8): 1098-1107.

- Conte K, Odden MC, Linton NM, Harvey SM (2016) Effectiveness of a scaled-up arthritis self-management program in Oregon: Walk With Ease. American Journal of Public Health 106(12): 2227-230.

- Nyrop KA, Charnock BL, Martin KR, Lias J, Altpeter M, et al. (2011) Effects of a six-week walking program on workplace activity limitations among adults with arthritis. Arthritis Care & Research 63(12): 1773-1776.

- Washburn RA, McAuley E, Katula J, Mihalko SL, Boileau RA (1999) The physical activity scale for the elderly (PASE): Evidence for validity. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 52(7): 643-651.

- Washburn RA, Smith KW, Jette AM, Janney CA (1993) The physical activity scale for the elderly: Development and evaluation. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 46(2): 153-162.

- Su R, Tay L, Diener E (2014) The development and validation of the Comprehensive Inventory of Thriving (CIT) and the Brief Inventory of Thriving (BIT). Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being 6(3): 251-279.

- R Core Team (2018) R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing.

- Petersen R, Pan L, Blanck HM (2019) Racial and ethnic disparities in adult obesity in the United States: CDC’s tracking to inform state and local action. Preventing Chronic Disease 16: E46.

-

Kimberly A Shaffer, Heather Hensman Kettrey, Sarah B King. Evaluating Physical Activity And Quality of Life For Older Adults Through Walk With Ease. Arch Rheum & Arthritis Res. 1(5): 2021. ARAR.MS.ID.000525.

-

Physical Activity, Arthritis, Sport, Obesity, Exercise

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.