Case Report

Case Report

A Case of Dermatomyositis presenting with Fulminant

Rhabdomyolysis without Myoglobinuric Acute Kidney

Injury-A Rare Clinical Manifestation

Richmond Ronald Gomes*1 and Saiful Bahar Khan2

1Department of medicine, Ad-din Women’s Medical College Hospital, Dhaka, Bangladesh

2Department of Nephrology, Ad-din Women’s Medical College Hospital, Dhaka, Bangladesh

Richmond Ronald Gomes*1 and Saiful Bahar Khan2

1Department of medicine, Ad-din Women’s Medical College Hospital, Dhaka, Bangladesh

2Department of Nephrology, Ad-din Women’s Medical College Hospital, Dhaka, Bangladesh

Richmond Ronald Gomes, Associate Professor, Department of Medicine, Ad-Din Women’s Medical College Hospital, Bangladesh.

Received Date: August 11, 2020; Published Date: August 26, 2020

Abstract

Rhabdomyolysis and myoglobinuria are a rare complication of dermatomyositis. Rhabdomyolysis has a wide range of presentations, from asymptomatic to life-threatening. The most dramatic presentation can result in acute renal failure, electrolyte imbalances, and/or disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC). Recognition of this fact has important therapeutic implications as patients require immunotherapy in addition to the symptomatic treatment for renal failure. Here we present a 30 year old male banker presented with progressive muscle pain and weakness for 10 days and high colored urine for 3 days. Laboratory findings suggested rhabdomyolysis. A diagnosis of dermatomyositis was based upon the proximal muscle weakness on both upper and lower limbs, skin lesion over face and upper trunk, elevated muscle enzyme levels, muscle biopsy and skin biopsy findings. The patient was managed with high dose prednisolone and steroid sparing agent. His muscle power did improve slightly. In our view, this is an interesting case in that dermatomyositis cause fulminant rhabdomyolysis without causing myoglobinuric acute kidney injury (AKI) due to direct toxic effect of myoglobulin on renal tubule.

Keywords: Dermatomyositis; Myoglobinuria; Rhabdomyolysis; Acute kidney injury

Introduction

Dermatomyositis (DM) and polymyositis (PM) are autoimmune idiopathic inflammatory myopathy characterized by chronic inflammation of skeletal muscle with infiltration of lymphocytes cutaneous findings with cutaneous involvement in dermatomyositis [1]. Although controversy still remains concerning the relationship between malignancy and myositis, most authorities agree that there is an increased incidence of malignancy in myositis patients, especially in the case of dermatomyositis (DM). For PM, however, the evidences which favor the association with malignancy is not sufficient than DM [2]. Myoglobinuria results from extensive muscle fiber necrosis and may be caused by traumatic causes or nontraumatic causes such as infection, drugs, or metabolic myopathies. Both polymyositis and dermatomyositis are rare causes of rhabdomyolysis, which occurs because of ongoing muscle fiber destruction. Recognition of this fact has important therapeutic implications as patients can land up in myoglobinuric acute renal failure due to acute tubular necrosis. There have been a few reported cases of PM with rhabdomyolysis leading to AKI requiring hemodialysis [3-6]. We report here an interesting case of dermatomyositis presenting with fulminant rhabdomyolysis but surprisingly without renal failure.

Case Presentation

A 30-year-old male banker, not known to have diabetes, hypertension, coronary artery disease or bronchial asthma presented with history of subacute onset of quadriparesis (lower limbs> upper limbs) of 10 days duration, generalized body ache and high colored urine of 3 days duration. His complaints started in the form of throbbing pain in both calf region which spread to whole of both lower limbs in one day. This was not associated with fever, trauma to the leg or back or any recent strenuous exercise recently. The patient denied ethanol ingestion and recent use of myotoxic drugs. Simultaneously, patient also developed tingling sensation in both lower limbs. After 2 days of onset, he noticed proximal muscle weakness in both lower limbs. Over the next 3 days, weakness progressed to involve the whole lower limb. Along with the lower limb involvement, he also noticed pain and proximal weakness in both upper limbs which progressed over next 3 days to involve the whole upper limb. After 1 week of onset she developed complete weakness of both upper and lower limbs along with dysphagia to both solid and liquids. He also complained of feeling of shortness of breath on exertion. But there was no involvement of any extraocular or facial muscles. On the 8th day of illness, he developed high colored urine and edema over face and feet. But his urine output was not reduced.

General examination revealed normal temperature, pulse rate of 90/min and a blood pressure of 130/90 mmHg. Respiratory rate was 22/min, oxygen saturation was 94% in room air and single breath count was 18. Chest auscultation was normal. Patient had bilateral pitting pedal edema and facial puffiness. There was no lymphadenopathy, pallor, cyanosis, icterus, or clubbing. A blackish brown rash was noted over anterior aspect of chest wall and back and over face (Figure1). Gottron’s papules over the knuckles and heliotrope rash was absent.

Neurological examination revealed truncal muscle weakness, hypotonia in all four limbs and marked weakness in proximal (1/5) and distal (3/5) group of muscles in both upper and lower limb muscles. These muscles were tender. Bilateral palatal movement was sluggish. Sensory system examination was normal. Deep tendon reflexes were diminished and plantars were not elicitable.

On investigation Complete blood count revealed Hemoglobin 14.2gm%, TLC-9530/cu mm, DC:N -82.5%, L-11%, E-0.4%, M-3.9%, immature granulocyte 2.1%, ESR-43 mm in 1st hour, platelet count-533000/cu mm, PBF- mild neutrophilic leukocytosis with thrombocytosis, RBS 5.7 mmol/L(normal 4.2-7.8 mmol/L), reticulocyte count –1.8%, blood urea-283mg%, serum creatinine- 0.5mg%(normal 0.6-1.3 mg%), serum sodium-136.2 mmol/ L(normal 135-145 mmol/L), serum potassium-3.67 mmol/L(normal 3.5-5.5 mmol/L),corrected serum calcium-7.42mg%(normal 8.5- 10.5 mg%), serum phosphorus-7.6mg%(normal 2.5-4.3 mg%), serum total protein-5.2gm%, serum albumin-3.1gm%(normal 3.5-5.2gm%), serum creatine phosphokinase-49548 IU/L (Normal value-30-170 IU/L). Serum aldolase 62 U/L (upto 7.60 U/L) normal TSH was slightly raised (6.69 mIU/ml, normal 0.4-5.2 mIU/ml).

Urine was brown colored (Coca-Cola colored) (Figure2) and microscopic examination revealed protein±2, RBC 1-2/HPF, pus cell 2-3/HPF, granular casts 8-10/HPF; Urine was positive for myoglobin (750 ng/L). Urine culture is negative. UTP was 3.74 gram/day (normal 0.04-0.23 gm/day).

Immunological screening like antinuclear antibodies, rheumatoid factor and C-reactive protein were normal. Screening for hepatitis B surface antigen, anti-HCV were negative. Chest X-ray and abdominal ultrasound were normal. Immunological investigations revealed negative ANA (7.42 AU/ml, normal <40) and Anti ds DNA (22.10 IU/ml, normal<35), normal C3(118mg/L, normal 88-140mg/L). Extractable nuclear antigen (ENA) profile showed positive anti Mi-2 antibody suggestive of dermatomyositis.

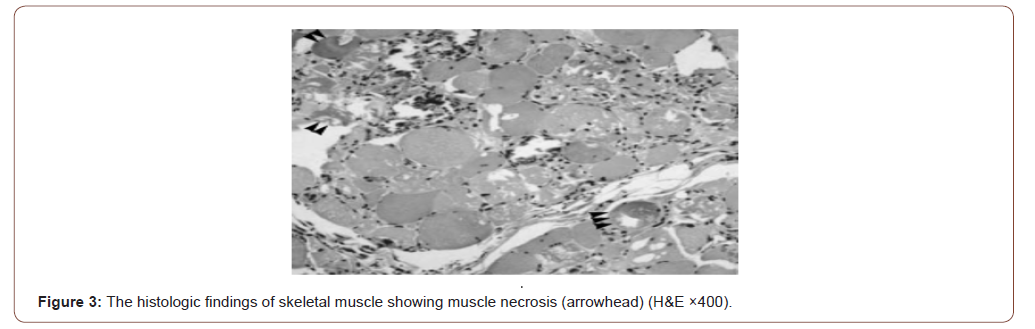

MRI of limb muscles could not be done due to financial constraints. Electrophysiological study and renal biopsy could not be done under corona circumstances. Muscle biopsy of proximal muscle (left vastus lateralis) showed spindle cells and round cells infiltrating skeletal muscles with perifascicular atrophy suggestive of proliferative inflammatory myositis with muscle necrosis (Figure 3).

Skin biopsy from forehead revealed hyperkeratosis and acanthosis of epidermis with regular elongation of rete ridges. The dermis showed increased collagen and perivascular infiltration of acute and chronic inflammatory cells.

Based on the characteristic rash with muscle weakness and biopsy features, a diagnosis of dermatomyositis with rhabdomyolysis with myoglobinuria was obtained. He was given high doses of methylprednisolone 1 gm/day for 3 days followed by oral prednisolone 1 mg/kg/day. Considering his skin involvement, weekly 10 mg methotrexate along with folic acid was also started as steroid sparing agent. ACE inhibitor perindopril was added as anti-protein uric agent along with calcium supplement and topical tacrolimus ointment. He had a dramatic clinical response with improvement in bulbar and respiratory symptoms noted within 3 days of starting treatment. But limb muscle power did improve slightly. During discharge, 10th day following admission his biochemical parameters improved with CPK reduced to 7450 IU/L. Repeat urine routine examination showed + protein with no RBC and no casts. UTP reduced to 2.12 gram/day. There is a plan for renal biopsy if urinary total protein show proteinuria persistently above 1gram/day on next follow up after 1 month. Also, there is a plan for rituximab or monthly pulse intravenous immunoglobulin therapy if limb muscle power show poor improvement.

Discussion: The prevalence of polymyositis and dermatomyositis is 5 to 22 per 100,000 patients, and the incidence is approximately 1.2 to 19 million persons at risk per year [7]. Dermatomyositis is an acquired muscle disease which results in chronic muscle inflammation and weakness. A classic skin rash may precede the muscle weakness. It is most commonly seen in adults between the ages 40 and 607. Most patients experience muscle aches and weakness of the more proximal muscles, which results in difficulty performing certain activities such as raising their arms over their head, climbing stairs, and swallowing. A reddish-purple heliotrope rash may develop over the eyelids and across the cheeks and bridge of the nose. Gottron papules can develop over the knuckles, elbows, knees, and other extensor regions; this appears as a scaling and red rash [8].Risk of developing dermatomyositis is higher in patients with other autoimmune disorders such as systemic lupus erythematous (SLE), rheumatoid arthritis, scleroderma, and Sjogren’s syndrome. Complications of dermatomyositis include difficulty swallowing and aspiration. Patients may experience dysfunctional breathing if chest muscles are affected, which may lead to shortness of breath and eventual respiratory failure [9]. On the matter about the association of malignancy and myositis, major excess risk was attributable to DM. PM is generally considered that there is much weaker relation with malignancy than DM.

Rhabdomyolysis is a syndrome where the body breaks down skeletal muscle fibers, which subsequently causes actin and myosin fibers to become necrotic. Eventually leakage of muscle contents into the circulation occurs. Approximately 26,000 cases of rhabdomyolysis are reported in America yearly, with 10% to 50% progressing to acute renal failure [10,11]. Mortality rates range from 7% to 80% and are higher in patients who develop multiorgan failure [12]. While the most common cause is direct muscle trauma, a wide range of processes precipitate, including autoimmune/ inflammatory myopathies [10,11].

Causes of rhabdomyolysis include:

1. Heat-related events, such as heatstroke and marathon running

2. Trauma, such as immobilization and crush injuries

3. Malignant hyperthermia, neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS), and other toxicological events

4. Endocrine problems, such as hypothyroidism, thyrotoxicosis, diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA)

5. Environmental events such as lightning strikes and thirddegree burns

6. Inflammatory processes such as polymyositis and dermatomyositis [13,14].

Features of rhabdomyolysis are often nonspecific10. Classically, rhabdomyolysis presents as a triad of symptoms that include:

1. Myalgia

2. Weakness

3. Myoglobinuria

However, only 10% of patients are seen to have the classic triad and about half of patients do not complain of muscle pain or weakness at all [13]. Instead, patients often present with discolored urine (tea or coca cola in color) as their chief complaint. Complications of rhabdomyolysis can be categorized into early and late. In the acute phase of rhabdomyolysis, hyperkalemia from severe muscle breakdown can cause cardiac arrhythmia and sudden cardiac arrest within the first 12 hours [10,15]. Approximately 15% of patients go on to experience the late complication of renal failure, which is secondary to the toxic effect of myoglobin on the renal tubules [13]. Acute kidney injury and diffuse intravascular coagulation are late complications that occur within 12-24 hours [13].

Myoglobinuria is usually the result of rhabdomyolysis or muscle destruction. Any process that interferes with the storage or use of energy by muscle cells can lead to myoglobinuria. The release of myoglobin from muscle cells is often associated with an increase in levels of creatine kinase (CK), aldolase, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), serum glutamic-oxaloacetic transaminase (SGOT) and serum glutamic-pyruvic transaminase (SGPT). When excreted into the urine, myoglobin, a monomer containing a heme molecule similar to hemoglobin can precipitate, causing tubular obstruction and acute renal insufficiency.

There have been case reports of dermatomyositis with myoglobinuria or renal failure with variable treatment outcomes both with and without malignancy [3,6,16-20]. Renal involvement in patients with polymyositis (PM)/dermatomyositis (DM) was previously thought to be uncommon, but two main types of renal lesion have been described [20]. First, acute tubular necrosis with renal failure related to myoglobulinemia and myoglobulinuria is a well-recognized feature of acute rhabdomyolysis. Second, chronic glomerulonephritis has been infrequently reported in a small group of patients with PM/DM. A retrospective study analyzed the records of 65 patients of polymyositis and dermatomyositis for investigating the incidence, severity, and prognosis of renal disease in PM/DM patients admitted to a single centre over a 10- year interval. Of the 65 patients, 14 were found to have suffered varying degree of renal involvement, and the incidence rate was 21.5%. All the 14 patients had varying degree of haematuria and proteinuria. Acute tubular necrosis with renal failure developed in four patients with PM and in five patients with DM. Renal biopsy in two DM patients with overt proteinuria revealed IgA nephropathy in one and membranous nephropathy in the other. The authors therefore concluded that renal involvement in PM/DM patients is not as uncommon as previously thought [21].

Testing should include a creatinine kinase and electrolyte and renal function panel to assess for acute renal dysfunction and elevated potassium. (CK levels help us identify rhabdomyolysis but do not indicate the prognosis [22]. Urinalysis will typically show blood on dipstick without red blood cells on microscopic evaluation. An EKG should be performed secondary to evaluation for cardiac toxicity of elevated potassium.

Inflammatory myopathies are diagnosed by characteristic historical and physical exam findings, such as proximal muscle weakness and evidence of effect on activities of daily living (e.g., asking the patient if they have difficulty with brushing their teeth or walking upstairs). Obtaining screening labs such as aldolase, ALT/AST, and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) can help in evaluating for underlying inflammatory myopathies. Although nonspecific, obtaining an erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) or C-reactive protein (CRP) can help evaluate for inflammation.

Antinuclear antibody (ANA) is another screening tool commonly used and obtaining specific antibodies such as Jo-1 antibodies and SSA/SSB can also aid in diagnosis. Further inpatient testing may include electromyography (EMG), which is able to evaluate for skeletal muscle activity during rest and activity. In inflammatory myopathies, this test will be abnormal. MRI can evaluate for inflammation in the muscle groups. The gold standard for diagnosis is with a muscle biopsy, which will show muscle degradation [8,23].

Treatment of rhabdomyolysis includes aggressive fluid administration to prevent renal injury. Most data indicate that acute kidney injury doesn’t increase until the CK level exceeds 5,000 units/L [11]. Intravenous hydration should be initiated immediately. Mannitol and bicarbonate are often used to supplement fluid resuscitation with normal saline. One study showed a protective effect with mannitol due to diuresis, which minimizes intratubular heme pigment deposition. Dialysis is another cornerstone of treatment modalities for rhabdomyolysis when renal failure and/ or refractory hyperkalemia occurs. Many patients with previously normal renal function and AKI due to rhabdomyolysis will recover intrinsic renal function, and not go on to permanent dialysis dependence [24]. Various forms of dialysis have been used for acute renal failure if it develops, but there is no evidence to support the use of a specific dialysis modality. It has been hypothesized that the use of dialysis functions to directly reduce circulating myoglobin [25,26].

Management of polymyositis and dermatomyositis includes corticosteroids as the initial therapy, especially in episodes of acute exacerbation of inflammation. Prednisone is dosed at 1 to 2 mg/ kg/day in most patients. In patients with severe weakness or extra muscular involvement, IV methylprednisolone 1 mg/day for 3 days can be used [26]. Patients should be monitored for steroidrelated adverse effects such as steroid induced myopathy, weight gain, hyperglycemia, hypertension, adrenal insufficiency, and osteoporosis. For prevention of acute episodes, patients may be started as outpatients on immunologic agents such as rituximab, which is an anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody. Tocilizumab (anti IL-6 antibody), anakinra (anti-IL 1 antibody), and alemtuzumab (anti CD52 antibody) are all options that may be started under the direct care of a rheumatologist [23,27].

Conclusion

Our patient developed fulminant rhabdomyolysis but without acute kidney injury and the development of the rash with muscle weakness and muscle biopsy features of inflammation with improvement in muscle weakness with steroids points to an underlying inflammatory muscle disease, dermatomyositis (DM). Recognition of this fact is important as this has therapeutic implication for starting immunotherapy in addition to the symptomatic dialysis, mannitol, alkalization, and hydration treatment for rhabdomyolysis. DM must be considered in the differential diagnosis of non-traumatic rhabdomyolysis and investigation for the associated malignancy, including HCC, should be included.

Acknowledgement

None.

Conflicts of Interest

No conflict of interest.

References

- Bohan A, Peter JB (1975) Polymyositis and dermatomyositis. N Engl J Med 292: 403-407.

- Yazici Y, Kagen LJ (2000) The association of malignancy with myositis. Curr Opin Rheumatol 12:498-500.

- Yum JH, Jung YK, Kim YH, Ahn BJ, Son JH, et al. (1999) A case of acute renal failure due to rhabdomyolysis associated with dermatomyositis in breast cancer. Korean J Nephrol 18: 334-338.

- Lewington AJ, D'Souza R, Carr S, O'Reilly K, Warwick GL (1996) Dermatomyositis: a cause of acute renal failure. Nephrol Dial Transplant 11: 699-701.

- Thakur V, De Salvo J, McGrath H, Weed S Garcia C (1996) Case report: Polymyositis-induced myoglobinuric acute renal failure. Am J Med Sci 312(2): 85-87.

- Caccamo DV, Keene CY, Durham J, Peven D (1993) Fulminant rhabdomyolysis in a patient with dermatomyositis. Neurology 43(4): 844-845.

- Cheeti A, Panginikkod S (2019) Dermatomyositis and polymyositis. StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing

- Marvi U, Chung L, Fiorentino DF (2012) Clinical presentation and evaluation of dermatomyositis. Indian J Dermatol 57(5): 375-381.

- Johns Hopkins (2020) Health Conditions and Diseases: Polymyositis.

- Sauret J, Marinides G, Wang G (2002) Rhabdomyolysis. Am Fam Physician 65(5): 907-913.

- Bosch X, Poch E, Grau JM (2009) Rhabdomyolysis and acute kidney injury. N Engl J Med 361(1): 62-72.

- Huerta Alardin AL, Varon J, Marik PE (2005) Bench-to-bedside review: rhabdomyolysis-an overview for clinicians. Crit Care 9(2): 158-169.

- Torres P, Helmstetter J, Kaye AM, Kaye AD (2015) Rhabdomyolysis: pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment. Oschsner J 15(1): 58-69.

- Vanholder R, Sever M, Erek E, Lameire N (2000) Rhabdomyolysis. J Am Soc Nephrol 11(8): 1553-1561.

- Khan FY (2009) Rhabdomyolysis: a review of the literature. Neth J Med 67(9): 272-283.

- Singhal PC, Narayanan Nampoory MR, Vishwesharan RK, Mehta RL, Gupta V, et al. (1985) Myoglobinuric renal failure associated with dermatomyositis. J Assoc Physicians India 33(10): 672-673.

- Park SK, Cho KH, Kang SK (1990) Acute renal failure associated with dermatomyositis and colon cancer. Nephron 55: 225-226.

- Kessler E, WeinbergerI, Rosenfeld JB (1972) Myoglobinuric acute renal renal failure in a case of dermatomyositis. Isr J Med Sci 8(7): 978-983.

- Chie A, Seji T, Hajime H, Kenji K, Takao KH (2001) A case of acute renal failure due to myoglobinuria with dermatomyositis. Kyushu J Rheumatol 20: 51-53.

- Rose MR, Kissel JT, Bickley LS, Griggs RC (1996) Sustained myoglobinuria: The presenting manifestation of dermatomyositis. Neurology 47(1): 119-123.

- Yen TH, Lai PC, Chen CC, Hsueh S, Huang JY Huang (2005) Renal involvement in patients with polymyositis and dermatomyositis. Int J Clin Pract 59(2): 188-193.

- Baeza Trinidad R, Brea Hernando A, Morera Rodriguez S, Brito Diaz Y, Sanchez Hernandez S, et al. (2015) Creatinine as predictor value of mortality and acute kidney injury in rhabdomyolysis 45(11): 1173-1178.

- Hunter K, Lyon MG (2012) Evaluation and management of polymyositis. Indian J Dermatol 57(5): 371-374.

- Sauret J, Marinides G, Wang G (2002) Rhabdomyolysis. Am Fam Physician 65(5): 907-913.

- Keltz E, Khan F, Mann G (2013) Rhabdomyolysis: the role of diagnostic and prognostic factors. Muscles Ligaments Tendons J 3(4): 303-312.

- Chatzizisis Y, Misirli G, Hatzitolios A, Giannoglou G (2008) The syndrome of rhabdomyolysis: Complications and treatment. Eur J Intern Med 19(8): 568-574.

- Greenberg SA (2008) Inflammatory myopathies: evaluation and management. Semin Neurol 28(2): 241-249.

-

Richmond Ronald Gomes. A Case of Dermatomyositis presenting with Fulminant Rhabdomyolysis without Myoglobinuric Acute Kidney Injury-A Rare Clinical Manifestation. Arch Rheum & Arthritis Res. 1(3): 2020. ARAR.MS.ID.000512.

-

Dermatomyositis, Myoglobinuria, Rhabdomyolysis, Acute kidney injury, Polymyositis, Rhabdomyolysis, Clinical manifestation, Acute renal failure

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.