Research Article

Research Article

Folk Medicine in Bangladesh: Healing with Plants by a Practitioner in Kushtia District

Jakera Shakera1, Rony Mandal1, Tanjina Akter2, Nusratun Nahar2 and Mohammed Rahmatullah1*

11Department of Biotechnology & Genetic Engineering, University of Development Alternative, Bangladesh

22Department of Pharmacy, University of Development Alternative, Bangladesh

Mohammed Rahmatullah Dean, Faculty of Life Sciences, University of Development Alternative, Lalmatia, Dhaka-1207, Bangladesh.

Received Date:July 22, 2019; Published Date: July 25, 2019

Abstract

Folk medicine or treatment by individuals without any formal training, supervision or registration is a common form of medicinal practice in Bangladesh and is generally done with whole plants or plant parts. Folk medicinal practitioners (FMPs) are a common feature in rural Bangladesh with practically every village having one or more FMPs. The unique feature of the FMPs is their remarkable diversity in the selection of plants for treatment. Since folk medicinal practice has been going on in Bangladesh for centuries, it follows that this system of practice has to be found beneficial by the patients or otherwise it would have disappeared a long time ago. As such, the various plants used by FMPs need to be documented for they can serve as important sources of novel drug discoveries. The objective of this study was to document the plant-based remedies of a rural FMP in Kushtia district, Bangladesh. The FMP was found to use a total of 12 plants in his treatment. The plants were distributed in twelve families and were used for the treatment of rheumatic fever, pain, piles, hormone disorders in male, skin disorders, leprosy, hernia, and antidote to poisoning. The advantage with herbal medicine lies in the availability and affordability of medicinal plants. If the FMP’s formulations prove to be scientifically sound, the plants can prove to be possibly a less expensive alternative to allopathic treatments. At the same time, these would create awareness and spur conservation of the plants, quite a few of which are rapidly becoming endangered in the wild.

Keywords:Folk medicine; Medicinal plants; Phytotherapy; Kushtia; Bangladesh

Introduction

The connection between humans and plants definitely exist since the dawn of human beings. Not only humans (Homo sapiens) possibly evolved into a world teeming with plants in the African late middle Pleistocene period [1], they also from the very start had to use the plants as sources of daily diet and nutrition, and quite possibly for therapeutic purposes. That plants may have served to cure diseases in early humans is borne out by various types of fossil records [2]. There are manifold ways how ancient humans learnt the therapeutic values of plants, like trial and error, through watching the behavior of the great apes and other animal species, who instinctively partake of some plants for medicinal purposes [3], and also possibly on the basis or organoleptic properties [4]. Plants produce secondary metabolites having pharmacological activities, which can prove useful in treatment of diseases. Considering the possibly more than 250,000 species of plant that exist in the world at present, this represents a huge number of different secondary metabolites with a huge potential for curing existing and emerging diseases.

Phytotherapy exists even in the present era in different forms and names in different parts of the world. In the Indian sub-continent countries some systems have become quite ritualized with their own definitive philosophy on causes, diagnosis and treatment of diseases. Modern or allopathic medicine has also benefitted from these traditional phytotherapeutic systems, and plants still play a major role in the discovery of new drugs. For instance, it has been reported that of the 877 new drug applications between 1981 and 2002, 49% were associated with plants [5]. Folk medicine, otherwise recognized as medicinal practice by non-registered and non-formally trained practitioners, is one of the ancient medicinal systems practiced throughout the world. In Bangladesh, folk medicinal practitioners (FMPs) possibly form the largest group of traditional medicinal practitioners. They mainly use plants for treatment (phytotherapy), although the extremely diverse sort of practice by the FMPs may occasionally include zootherapy and use of amulets and incantations. Till fairly recent periods, most FMPs if not all, were decried by allopathic practitioners as frauds or quacks. However, in recent times, the focus has shifted on FMPs and their capabilities to form the first tier of treatment givers, more so in underdeveloped countries lacking adequate doctors, medical facilities, transport systems, and a literate population. Our previous studies have shown that FMPs can possess a remarkable and diverse knowledge of medicinal plants [6-27]. To gain more knowledge about folk medicinal practice, the objective of the present study was to document the medicinal plants used by a FMP in a village of Kushtia district, Bangladesh. Such studies, although gaining more attention, are still inadequate considering the quite large numbers of practicing FMPs within the country.

Methods

The FMP was named Abdul Jalil, male, with age not disclosed. He practiced in the villages of Taragonia and Mothurapur in Daulatpur Upazila (sub-district) in Kushtia district, Bangladesh. The sub-district had a total number of 246 villages with an area of 468.76 square kilometer and a population density of 946 per square kilometer. Kushtia district is located in between 23°42’ and 24°12’ north latitudes and in between 88°42’ and 89°22’ east longitudes with an area of 1621.15 sq km. Prior informed consent was initially obtained from the FMP. The FMP was informed the reason for our visit and consent obtained to disseminate any information provided including his name both nationally and internationally. Actual interviews were conducted in the Bengali language, which was spoken fluently by the FMP as well as the interviewers, the language being the mother tongueof both FMP, villagers and the interviewers. The interviews were conducted with the help of a semi-structured questionnaire and the guided fieldwalk method of Martin [28] and Maundu [29]. In this method the FMP took the interviewers to areas, where he collected medicinal plants for therapeutic purposes. The FMP showed the interviewers a number of plants and described their therapeutic uses. All plant specimens shown by him were collected on the spot, pressed, dried and brought back to Dhaka for identification by a competent botanist. Voucher specimens were deposited with the Medicinal Plant Collection Wing of the University of Development Alternative.

Results and Discussion

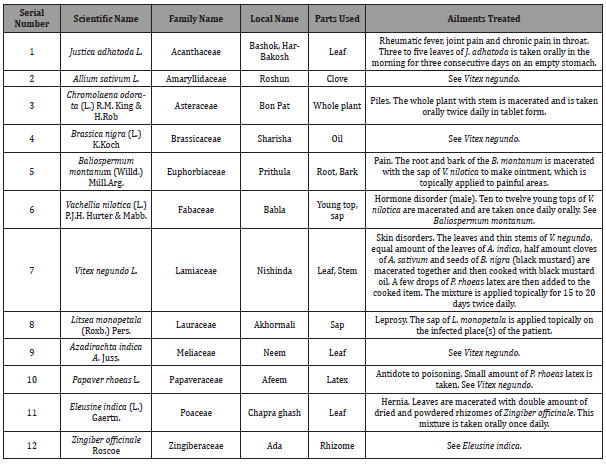

The FMP was observed to use a total of 12 plants distributed into 12 families for treatment of various diseases. The plants were used for the treatment of rheumatic fever, pain, piles, and hormonal disorders in male, skin disorders, leprosy, hernia, and antidote to poisoning. The results are shown in (Table 1).

Table 1:

Justicia adhatoda is normally used in Bangladesh for respiratory disorders in folk medicinal systems [30]. Leaves are taken as tea or taken whole. So the use of leaves of this plant for treatment of rheumatic fever, joint pain and chronic pain in throat is not a common usage. A recent review on the pharmacological activities of the plant also do not mention about any analgesic properties of any part of the plant [31]. As such, the use of this plant by the FMP to treat pain opens up new possibilities of both acute and chronic pain treatment. This is important, because over the counter drugs for pain treatment like aspirin or paracetamol on prolonged taking or over-dosage leads to gastric ulceration and hepatotoxicity, respectively. The FMP used whole plant of Chromolaena odorata for treatment of piles. Treatment of piles by leaf extract has been reported from Nigeria [32]. Increased fiver intake is considered by doctors as an indirect treatment for piles (hemorrhoids) as such intake can soften stools [33]. The plant can be a source for fiber; however, ethanol extract of the plant has been shown to cause hepatotoxicity in Wistar rats [34]. The roots of Baliospermum montanum and sap of Vachellia nilotica were used by the FMP to alleviate pain. Analgesic activity of the roots of B. montanum has been reported [35]. The use of V. nilotica, on the other hand, seems to be the first report of its kind.

The leaves of Vitex negundo were used by the FMP for treating skin disorders. This use is supported by the Ayurvedic and Unani Pharmacopoeia of India [36]. The FMP furthermore used leaves of Azadirachta indica, half amount cloves of Allium sativum and seeds of Brassica nigra with V. negundo. A. indica and A. sativum are scientifically proven plants against various skin disorders [37]. The oil from B. nigra may have an enhancing effect on the absorption of phytochemicals in the skin. The Garo tribals use the plant Litsea monopetala for treatment of diabetes, diarrhea, dysentery, and arthritis [38]. The present FMP used the plant to treat leprosy. In Parsa district, Nepal, the plant is also used to treat diarrhea and dysentery [39]. Treatment of leprosy with this plant appears to be a new therapeutic way to use this plant. People affected by leprosy are looked down in Bangladesh and if the FMP’s treatment can be scientifically validated, it may offer an easy method for curing this disease. The same applies to Papaver rhoeas and Eleusine indica, respectively used by the FMP as an antidote to poison and for treatment of hernia. Both treatment appears to be novel and described for the first time to our knowledge. P. rhoeas is used in North Khorasan Province of Iran as a sedative [40]. In Central Uganda various medicinal plants are used to treat hernia. The frequently used plants include Cyphostemma adenocaule, Shirakiopsis elliptica, Citrullus colocynthis, and Ocimum americanum[41].

Conclusion

Overall, our findings suggest that the phytotherapeutic methods of the present FMP were quite novel. These distinctive therapeutic uses of plants by various FMPs make this profession interesting and offer scientists the opportunity to conduct research on new plant species in human being’s perpetual quest for new and more effective drugs.

Acknowledgement

The authors are grateful to the FMP for providing information on his phytotherapeutic practices.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Stringer CB (2016) The origin and evolution of Homo sapiens. Phil Trans Royal Soc B Biol Sci 371: 20150237.

- Mamedov NA, Craker LE (2012) Man and medicinal plants: a short review. Acta Hort 964.

- Newton P (1991) The use of medicinal plants by primates: A missing link? Trends Ecol Evol 6(9): 297-299.

- Leonti M, Sticher O, Heinrich M (2002) Medicinal plants of the Populace, Mexico: Organoleptic properties as indigenous selection criteria. J Ethnopharmacol 81(3): 307-315.

- Verpoorte R, Kim HK, Choi YH (2005) Plants as source of medicines. In: RJ Bogers, LE Craker, D Lange (Eds.), Medicinal and Aromatic Plants: Agricultural, Commercial, Ecological, Legal, Pharmacological and Social Aspects. Springer, Heidelberg, Germany, pp. 261-273.

- Rahmatullah M, Ferdausi D, Mollik MAH, Jahan R, Chowdhury MH, et al. (2010) A Survey of Medicinal Plants used by Kavirajes of Chalna area, Khulna District, Bangladesh. Afr J Tradit Complement Alternat Med 7(2): 91-97.

- Rahmatullah M, Khatun MA, Morshed N, Neogi PK, Khan SUA, et al. (2010) A randomized survey of medicinal plants used by folk medicinal healers of Sylhet Division, Bangladesh. Adv Nat Appl Sci 4(1): 52-62.

- Rahmatullah M, Kabir AABT, Rahman MM, Hossan MS, Khatun Z, et al. 2010 Ethnomedicinal practices among a minority group of Christians residing in Mirzapur village of Dinajpur District, Bangladesh. Adv Nat Appl Sci 4(1): 45-51.

- Rahmatullah M, Momen MA, Rahman MM, Nasrin D, Hossain MS, et al. (2010) A randomized survey of medicinal plants used by folk medicinal practitioners in Daudkandi sub-district of Comilla district, Bangladesh. Adv Nat Appl Sci 4(2): 99-104.

- Rahmatullah M, Mollik MAH, Ahmed MN, Bhuiyan MZA, Hossain MM, et al. (2010) A survey of medicinal plants used by folk medicinal practitioners in two villages of Tangail district, Bangladesh. Am-Eur J Sustain Agric 4(3): 357-362.

- Rahmatullah M, Mollik MAH, Islam MK, Islam MR, Jahan FI, et al. (2010) A survey of medicinal and functional food plants used by the folk medicinal practitioners of three villages in Sreepur Upazilla, Magura district, Bangladesh. Am-Eur J Sustain Agric 4(3): 363-373.

- Rahmatullah M, Jahan R, Khatun MA, Jahan FI, Azad AK, et al. (2010) A pharmacological evaluation of medicinal plants used by folk medicinal practitioners of Station Purbo Para Village of Jamalpur Sadar Upazila in Jamalpur district, Bangladesh. Am-Eur J Sustain Agric 4(2): 170-195.

- Rahmatullah M, Ishika T, Rahman M, Swarna A, Khan T, et al. (2011) Plants prescribed for both preventive and therapeutic purposes by the traditional healers of the Bede community residing by the Turag River, Dhaka district. Am-Eur J Sustain Agric 5(3): 325-331.

- Rahmatullah M, Azam MNK, Rahman MM, Seraj S, Mahal MJ, et al. (2011) A survey of medicinal plants used by Garo and non-Garo traditional medicinal practitioners in two villages of Tangail district, Bangladesh. Am-Eur J Sustain Agric 5(3): 350-357.

- Rahmatullah M, Biswas KR (2012) Traditional medicinal practices of a Sardar healer of the Sardar (Dhangor) community of Bangladesh. J Altern Complement Med 18(1): 10-19.

- Rahmatullah M, Hasan A, Parvin W, Moniruzzaman M, Khatun A, et al. (2012) Medicinal plants and formulations used by the Soren clan of the Santal tribe in Rajshahi district, Bangladesh for treatment of various ailments. Afr J Tradit Complement Alternat Med 9(3): 350-359.

- Rahmatullah M, Khatun Z, Hasan A, Parvin W, Moniruzzaman M, et al. (2012) Survey and scientific evaluation of medicinal plants used by the Pahan and Teli tribal communities of Natore district, Bangladesh. Afr J Tradit Complement Alternat Med 9(3): 366-373.

- Rahmatullah M, Azam MNK, Khatun Z, Seraj S, Islam F, et al. (2012) Medicinal plants used for treatment of diabetes by the Marakh sect of the Garo tribe living in Mymensingh district, Bangladesh. Afr J Tradit Complement Alternat Med 9(3): 380-385.

- Rahmatullah M, Khatun Z, Barua D, Alam MU, Jahan S, et al. (2013) Medicinal plants used by traditional practitioners of the Kole and Rai tribes of Bangladesh. J Altern Complement Med 19(6): 483-491.

- Rahmatullah M, Pk SR, Al-Imran M, Jahan R (2013) The Khasia tribe of Sylhet district, Bangladesh, and their fast-disappearing knowledge of medicinal plants. J Altern Complement Med 19(7): 599-606.

- Akter S, Nipu AH, Chyti HN, Das PR, Islam MT, et al. (2014) Ethnomedicinal plants of the Shing tribe of Moulvibazar district, Bangladesh. World J Pharm Pharmaceut Sci 3(10): 1529-1537.

- Azad AK, Mahmud MR, Parvin A, Chakrabortty A, Akter F, et al. (2014) Medicinal plants of a Santal tribal healer in Dinajpur district, Bangladesh. World J Pharm Pharmaceut Sci 3(10): 1597-1606.

- Azad AK, Mahmud MR, Parvin A, Chakrabortty A, Akter F, et al. (2014) Ethnomedicinal surveys in two Mouzas of Kurigram district, Bangladesh. World J Pharm Pharmaceut Sci 3(10): 1607-1620.

- Kamal Z, Bairage JJ, Moniruzzaman, Das PR, Islam MT, et al. (2014) Ethnomedicinal practices of a folk medicinal practitioner in Pabna district, Bangladesh. World J Pharm Pharmaceut Sci 3(12): 73-85.

- Anzumi H, Rahman S, Islam MA, Rahmatullah M (2014) Uncommon medicinal plant formulations used by a folk medicinal practitioner in Naogaon district, Bangladesh. World J Pharm Pharmaceut Sci 3(12): 176-188.

- Esha RT, Chowdhury MR, Adhikary S, Haque KMA, Acharjee M, et al. (2012) Medicinal plants used by tribal medicinal practitioners of three clans of the Chakma tribe residing in Rangamati district, Bangladesh. Am.-Eur J Sustain Agric 6(2): 74-84.

- Malek I, Miah MR, Khan MF, Awal RBF, Nahar N, et al. (2014) Medicinal plants of two practitioners in two Marma tribal communities of Khagrachhari district, Bangladesh. Am.-Eur J Sustain Agric 8(5): 78-85.

- Martin GJ (1995) In: Ethnobotany: a ‘People and Plants’ Conservation Manual, Chapman and Hall, London, England, p. 268.

- Maundu P (1995) Methodology for collecting and sharing indigenous knowledge: a case study. Indigenous Knowledge and Development Monitor 3(2): 3-5.

- Karim MS, Rahman MM, Shahid SB, Malek I, Rahman MA, et al. (2011) Medicinal plants used by the folk medicinal practitioners of Bangladesh: a randomized survey in a village of Narayanganj district. Am.-Eur J Sustain Agric 5(4): 405-414.

- Khan I, Ahmad B, Azam S, Hassan F, Nazish, Aziz A, et al. (2018) Pharmacological activities of Justicia adhatoda. Pak J Pharm Sci 31(2): 371-377.

- Kigigha LT, Zige DV (2013) Activity of Chromolaena odorata on enteric and superficial etiologic bacterial agents. Am J Res Commun 1(11): 266-276.

- Sun Z, Migaly J (2016) Review of hemorrhoid disease: Presentation and management. Clin Colon Rectal Surg 29(1): 22-29.

- Anyanwu S, Eno EO, Inyang IJ, Asemota EA, Okpokam DC, et al. (2018) Evaluation of hepatotoxicity associated with ethanolic extract of Chromolaena odorata in Wistar rat model. IOSR J Dent Med Sci 17(7): 1-8.

- Nayak S, Sahai A, Singhai AK (2003) Analgesic activity of the roots of Baliospermum montanum Linn. Anc Sci Life 23(2): 108-113.

- Bano U, Jabeen A, Ahmed A, Siddiqui MA (2015) Therapeutic uses of Vitex negundo. World J Pharm Res 4(12): 589-606.

- Tabassum N, Hamdani M (2014) Plants used to treat skin diseases. Pharmacogn Rev 8(15): 52-60.

- Yeasmin M, Karmaker S, Hossain MS, Ahmed S, Tabassum A, et al. (2015) A case study of an urban Garo tribal medicinal practitioner in Mymensingh district, Bangladesh. World J Pharm Pharm Sci 4(12): 70-78.

- Singh S (2017) Ethnobotanical study of wild plants of Parsa district, Nepal. ECOPRINT 24: 1-12.

- Nadaf M, Joharchi MR, Amiri MS (2019) Ethnomedicinal uses of plants for the treatment of nervous disorders at the herbal markets of Bojnord, North Khorasan Province, Iran. Avicenna J Phytomed 9(2): 153-163.

- Kibuuka MS, Anywar G (2015) Medicinal plant species used in the management of hernia by traditional medicine practitioners in Central Uganda. Ethnobot Res Appl 14: 289-298.

-

Jakera Shakera, Rony Mandal, Tanjina Akter, Nusratun Nahar, Mohammed Rahmatullah. Folk Medicine in Bangladesh: Healing with Plants by a Practitioner in Kushtia District. Arch Phar & Pharmacol Res. 1(5): 2019. APPR.MS.ID.000525.

-

Folk medicine, medicinal plants, phytotherapy, Kushtia, Bangladesh, Homo sapiens, pharmacological activities, secondary metabolites, allopathic, folk medicinal practitioners, internationally, semi-structured questionnaire, field-walk method and Chromolaena odorata

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.