Research Article

Research Article

Common Neuropsychiatric Drug Interactions in Egypt That Require Clinical Interventions: A Retrospective Study in Delta Region

Mohamed Y Abdelgaied1, Khloud Shendy2, Omar Abdelmagged2, Naira Galal2, Mai Tarek2, Abdalla Essa2, Amr Zakaria3, Noran El-tabakh2, Hind Bakloul2, Khaled Abdelkawy4 and Michael G Zaki5*

1Faculty of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences, University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB, T6G 2E1, Canada

2BSc of Pharmacy, Faculty of Pharmacy, Kafrelsheikh University, Kafrelsheikh, Egypt

3MSC of clinical pharmacy, Department of Clinical Pharmacy, faculty of pharmacy, Horus University, Gamasa, Egypt

3Assistant professor of clinical pharmacy, Department of Clinical Pharmacy, Faculty of Pharmacy, Kafrelsheikh University, Kafrelsheikh, Egypt

3Assistant professor of Pharmaceutical Sciences, School of Pharmacy and Health Sciences, Fairleigh Dickinson University, 230 Park Avenue, Florham Park, New Jersey, 07932, USA

Michael G Zaki, School of Pharmacy and Health Sciences, Fairleigh Dickinson University, 230 Park Avenue, Florham Park, New Jersey, USA.

Received Date:February 02, 2024; Published Date:March 15, 2024

Abstract

Background: Drug-drug interactions (DDIs) are a major concern in patients with complex therapeutic regimens. The increasing incidence

of neuropsychiatric disorders gives more attention to neuropsychiatric drug interactions in clinical practice. However, limited reports of

neuropsychiatric DDIs are available. This study aimed to identify neuropsychiatric DDIs that require clinical intervention in Egyptian outpatients’

prescriptions.

Methods and Materials: An observational retrospective study was performed on Egyptian outpatients with different neuropsychiatric disorders

in Delta region of Egypt. Prescriptions were analyzed for potential drug-drug using the Lexicomp® DDI database. Potential DDIs included both

“D” and “X” risk ratings. Data were analyzed for incidence, Mechanism of action, major interacting therapeutic classes and outcomes. Descriptive

statistics were used to calculate the incidence of a potential drug interaction.

Results: A total of 4341 outpatients’ prescriptions were analyzed. Among them, 623 prescriptions were identified with at least one potentially

interacting drug combination. The overall incidence rate of potential drug interactions was 14%. It was found that 86 prescriptions contained

neuropsychiatric potential drug- drug interactions.

Conclusion: This increased incidence of neuropsychiatric DDIs shows that Egyptian outpatients are at a high risk of medication errors that can

be prevented. This emphasizes the need for checking DDI during prescription writing and dispensing. In addition, providing DDI related information

to the prescribers can play a vital role in minimizing the incidence rate of DDI.

Keywords:Neuropsychiatric; Drug Interaction; Lexicomp

Abbreviations:DDIs: Drug-drug interactions; ADRs: adverse drug reactions; COMT inhibitors: catechol-O-methyltransferase inhibitors; TCAs: Tricyclic Antidepressants; SSRIs: Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors; SNRIs: Serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors; CYP450: Cytochrome P450

Introduction

With the increasing burden of patients with multiple disease states and drug combinations, pharmacotherapy has become more complex [1]. The polytherapeutic regimens increase the risk of drug-drug interaction (DDI) to a great extent. DDIs occur when the effect of one drug is altered by the concurrent administration of another medication. Drug interactions are not only attributed to interactions to other drugs but also natural supplements and food. Drug interactions can occur either by pharmacokinetic or pharmacodynamics mechanisms [2]. Pharmacokinetic drug interactions occur when the concurrently administered drug has a potential to alter one of the pharmacokinetic parameters; absorption, distribution, metabolism and excretion of the other drug [3]. On the other hand, pharmacodynamic drug interactions occur if concurrently administered drugs have agonist or antagonist effects for either therapeutic efficacy or adverse effects [3]. Outcomes from DDIs can lead to severe adverse drug reactions (ADRs) resulting in hospitalizations and life-threatening conditions. About 6-30% of all ADRs are attributed to DDIs [4]. Furthermore, ADR caused by DDIs accounts for about 2.8% of hospital admission every year in USA [5]. In addition, DDIs may result in diminished or increased therapeutic effect or adverse effects of one or both medications.

Recent treatment guidelines of neuropsychiatric disorders usually involve many therapeutic regimens [6]. The therapeutic classes for neurological disorders include dopamine agonists, catechol-o-methyltransferase “COMT” inhibitors and anticholinergic drugs for Parkinson’s Disease and benzodiazepines and carbamazepine for epilepsy. In addition, the study involved some of the most common anti-depressants such as tricyclic anti-depressants (TCAs), selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) and antipsychotics for bipolar disorders [6,7]. It is noteworthy that multiple drug administration increases the potential for significant drug interactions in clinical practice affecting both therapeutic efficacy and adverse drug events of medications [7,8]. However, there are no previous reports about the incidence of potential drug interactions with patients treated with medications for neuropsychiatric disorders in Egypt. Incidence and pattern of these DDIs in Egypt are not well-documented and little information is available. For this reason, this study aimed to identify the potential drug interactions with neuropsychiatric drugs for outpatients in Egypt giving insights about incidence, mechanisms, outcomes and major interacting therapeutic classes.

Methods

An observational retrospective study was performed on Egyptian outpatients who got their medications dispensed from Egyptian community pharmacies in Delta region of Egypt. The Delta region includes five Governorates “Kafrelsheikh, Menoufia, Gharbia, Damnhour, Dakahlia”. Patients aged 18 years or older were included in the study. The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Kafrelsheikh University according to Helsinki declaration. All participants gave their consent forms. Prescriptions were collected over a 12 months-period from January 1, 2020, till January 1, 2021, to ensure that drugs commonly prescribed in all environmental seasons are included. Neuropsychiatric and neurological disorders that were included in this study were epilepsy, Parkinson’s Disease, Alzheimer’s Disease, depression. Pharmacological classes for neurologic disorders included Anti-parkinsonian medications (dopamine agonist, catechol-o-methyltransferase “COMT” inhibitors and anticholinergic) and antiepileptic drugs (benzodiazepines, valproic acid, phenytoin, carbamazepine, gabapentin, pregabalin and piracetam). Pharmacological classes for psychiatric disorders that were included in the study include TCAs (amitriptyline, clomipramine), SSRI (citalopram, dapoxetine, escitalopram, fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, paroxetine, sertraline), SNRIs (duloxetine) and hypericum perforatum for depression and anti-psychotic drugs (olanzapine, clozapine, quetiapine, chlorpromazine, and sulpiride).

Lexicomp Analysis: All prescriptions contained neuropsychiatric drugs were analyzed for potential drug-drug interactions using lexicomp® (Lexicomp, Inc., Ohio, USA) DDI database. In Lexicomp, a potential DDI can take a five-risk rating category from A, B, C, D and X which reflects both the level of urgency and the actions necessary to overcome the interaction. While category A has no reported drug interactions, category B and C are where there is a potential less serious DDI that does not require any action or to monitor therapy; respectively. Potential DDIs included in this report are either “D” and “X”-risk ratings since they include serious DDI that require modification of drug therapy or avoiding drug combinations; respectively. Data were analyzed for incidence, major interacting therapeutic classes, outcomes and mechanisms of actions.

Statistical analysis: Descriptive statistics were used to calculate the incidence of a potential dug interaction. All the statistical analysis was carried out with Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS, IBM corporation version 16.0) considering P < 0.01 as statistically significant.

Result

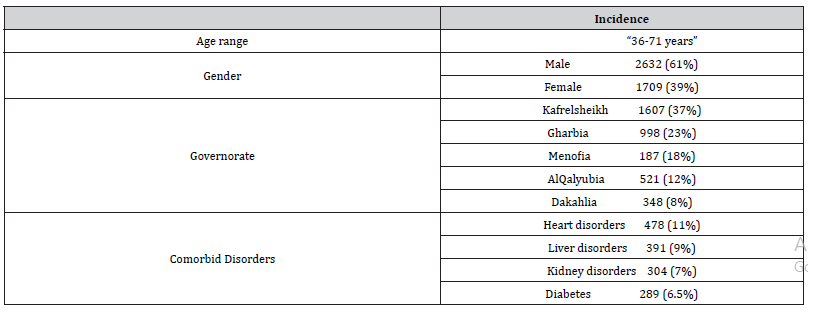

Exactly 4341 prescriptions were included in the study and analyzed. Participants demographics were presented in the (Table 1).

Table 1:Basic Patients Demographic data.

As revealed from (Figure 1), 623 potential drug interactions were identified. The overall incidence for potential drugdrug interactions was 14%. Only 86 potential interactions with neuropsychiatric drugs were reported (2% of the overall prescription). About 16 interactions for every one thousand prescriptions showed category D interactions. On the other hand, about 4 interactions for every one thousand prescriptions showed category X interactions.

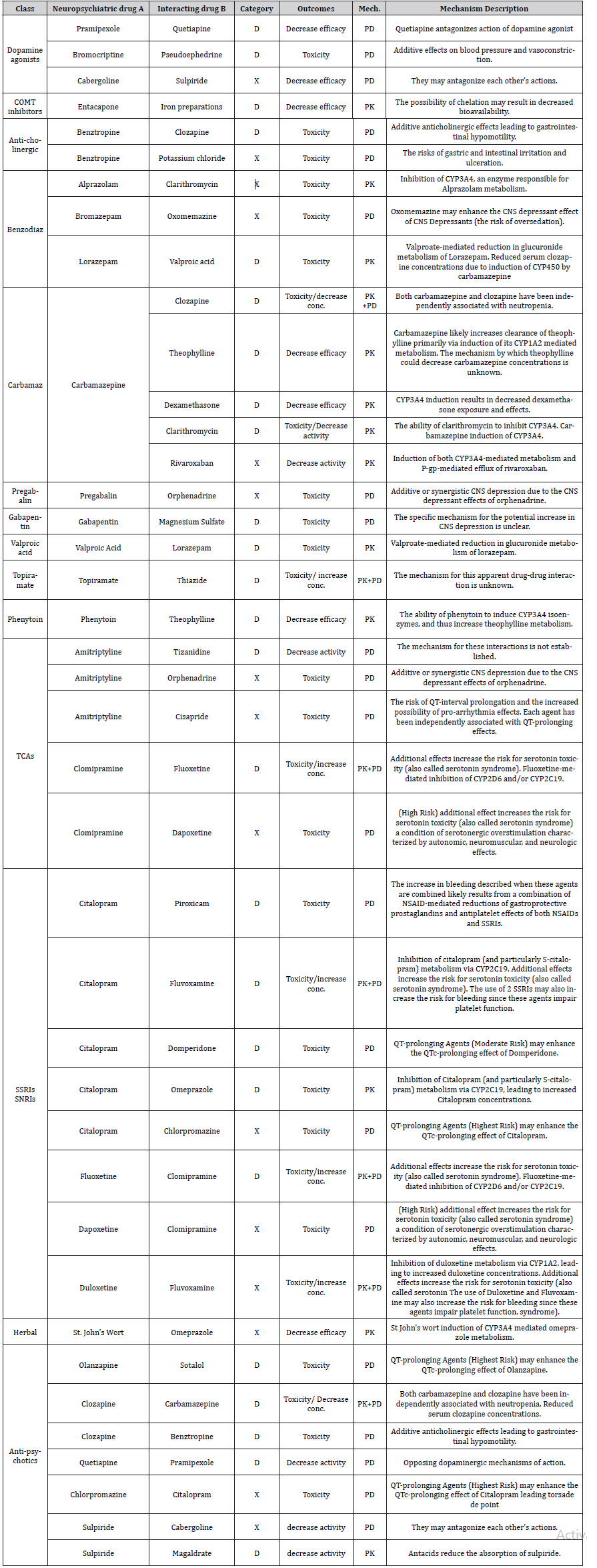

(Table 2) shows the list of potential DDI with neuropsychiatric drugs “risk rating D or X”. As shown from the table, the outcomes and mechanisms of drug interactions varied according to the nature of the drug.

Table 2:List of potential drug interactions with neuropsychiatric drugs.

Pk: Pharmacokinetics, PD: Pharmacodynamics, COMT: Catechol-o-methyl-transferase, CYP: Cytochrome, TCA: Tricyclic antidepressants, SSRI: selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, SNRI: serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors Benzodiaz: Benzodiazepine, Carbamaz: Carbamazepine, NSAIDs: Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

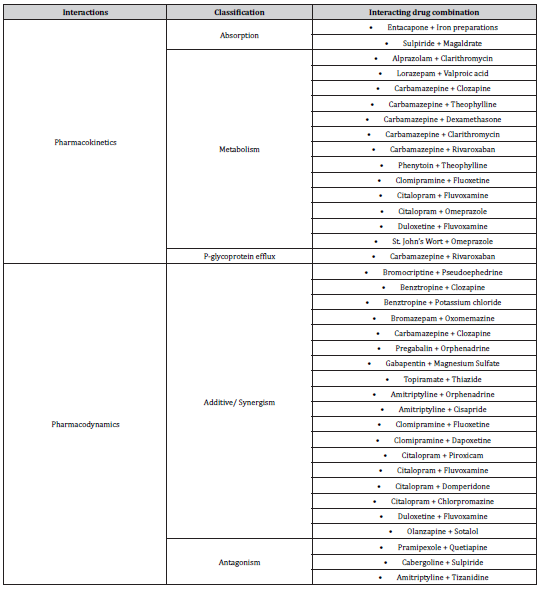

In addition, (Table 3) revealed the different mechanisms of neuropsychiatric drug interactions. Additive pharmacodynamic effects were the main mechanisms for interactions with antipsychotics and antidepressants. While metabolic inhibitions or induction of CYP450 were the main mechanisms for interactions with antiepileptic drugs.

Table 3:Mechanisms of neuropsychiatric drug interactions.

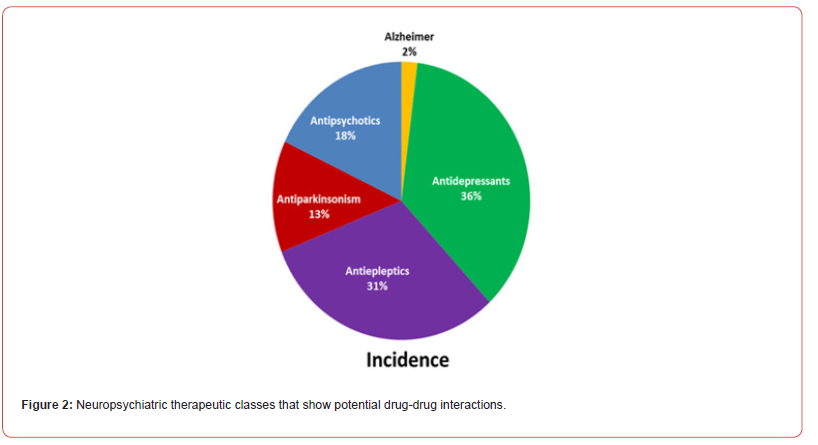

The incidence of drug interactions with neuropsychiatric according to pharmacological classes was shown in (Figure 2). The three major therapeutic classes representing 85% of potential interaction were antidepressants, antiepileptic, and antipsychotic drugs 36%, 31%, and 18%, respectively [7-9]. Similarly, the three major pharmacological classes representing 50% of potential interactions were SSRI, antipsychotics, and carbamazepine 20%, 18% and 12%, respectively [8,10-12].

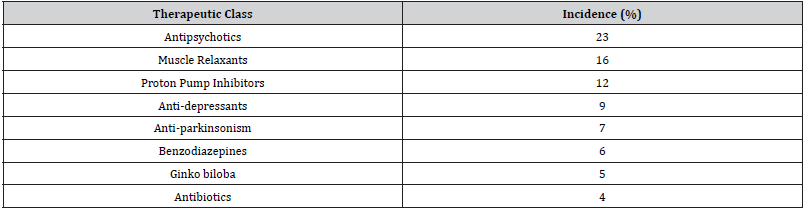

(Tables 4) showed major therapeutic classes of drugs that interact with neuropsychiatric drug. The three major therapeutic classes “represent 51% of potential interaction” were antipsychotics, muscle relaxants, and proton pump inhibitors 23%, 16%, and 12%, respectively. Consequently, these classes required more attention when prescribed with neuropsychiatric drugs to avoid any probable drug interactions.

Table 4:Major therapeutic classes that interact with neuropsychiatric drug.

Pearson correlation coefficient revealed that there was no significant correlation between reported risk factors “liver disorders, renal disorders, heart disorders, diabetes” and incidence and/or severity of drug interactions with neuropsychiatric diseases.

Discussion

Most neuropsychiatric patients take many drugs meaning many drugs per prescription in recent guidelines. This polypharmacy increases the likelihood of DDIs [7,13]. To our knowledge, this study was the first one that evaluates neuropsychiatric DDIs in Egyptian outpatients´ prescriptions. This study showed that that Incidence of potential neuropsychiatric DDIs in Egypt was 14% of neuropsychiatric DDIs. This study explored the importance of the preventive program to avoid potential medication errors in clinical practice and to avoid any hazardous effects of these interactions on Egyptian patients.

The major interacting classes were antidepressants, antiepileptic, and antipsychotic drugs. This shows the importance of giving more attention to these therapeutic classes in clinical practice. These classes require drug interaction evaluation with other concurrent drugs before dispensing their prescriptions. In pharmacy practice, the significant role of the pharmacist in checking prescription for any possible interaction with these therapeutic classes should be emphasized to prevent possible medication errors and avoiding any expected harmful outcomes [14].

As reported from this study, awareness of mechanisms of DDIs is very crucial to expect possible similar interactions with similar drugs in the therapeutic classes and whether the interactions are drug specific or class specific. In addition, being alert full of potential DDIs help suggest the possible alternative to avoid these interactions. This study showed that pharmacodynamic effects on dopamine and serotonin receptors were the main mechanisms for interactions with antipsychotics and antidepressants. While metabolic alterations of CYP450 mainly CYP3A4 were the main mechanisms for interactions with antiepileptic drugs.

Previous studies found similar results considering the association between patient characteristics and the prediction DDI. Abolhassani et al. studied 17,742 adult patients discharged between 2009 and 2015 from a department of internal medicine at Swiss hospital [15]. They found that age, number of comorbidities and a higher Charlson Comorbidity Index independently associated with polypharmacy. Similarly, Pérez et al. studied 38,299 patients in Ireland between 2012 and 2015 and found that age and multimorbidity were associated with a higher risk of DDI [15]. Furthermore, they found that hospital admissions themselves were independently associated with a higher risk of DDIs.

Limitations of this study include that these studies did not investigate psychiatric inpatients. To the best of our knowledge, there is currently no evidence comparable in scale and scope investigating the prediction of polypharmacy and the risk of DDI in hospital psychiatric units. Predicting other outcomes in hospitalized patients has often been found to be more complex in psychiatry than in other medical disciplines [16-18]. There are many reasons contributing to the difficulty of studying DDIs in psychiatric inpatients including less distinct diagnostic concepts, less standardization of care and a broader spectrum of acceptable therapeutic regimes [19-24]. Further studies are required to evaluate the DDIs in neuropsychiatric inpatients. In addition, prescription for pediatrics and more regions from different governorates of Egypt should be included in further studies. Also, natural supplements and herbal products including beverages and juices like green tea and grapefruit juices should be considered in further drug interactions evaluations [25-26].

Conclusion

Egyptian outpatients taking neuropsychiatric drugs are at a high risk of hazardous DDIs as revealed from the reported incidence from prescription. This emphasizes the need for the evaluation of potential DDIs during prescription writing to protect patients from harmful outcomes of drug interactions. In addition, providing DDIrelated information to the prescribers and using drug interaction software programs to the dispensing pharmacist can play a vital role in minimizing the incidence rate of DDIs. The preventive program monitoring for interactions outcome and increasing awareness of potential drug interaction are recommended in clinical practice in Egypt.

Author contributions

Khaled Abdelkawy conceived of the research and study design and revised the manuscript. All authors contributed to data collection and statistical analysis. Mohamed Abdelgaied wrote the first draft of the manuscript. Michael G Zaki and Khaled Abdelkawy revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgement

None.

Conflict of Interest

No Conflict of Interest.

References

- Roger Walker, Clive Edwards (2010) Clinical Pharmacy and Therapeutics (3rd Edition) London: Churchill Livingstone, 2003. Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology 55(12): 1709-1709.

- Niu J, RM Straubinger, DE Mager (2019) Pharmacodynamic Drug-Drug Interactions. Clin Pharmacol Ther 105(6): 1395-1406.

- Aparasu R, R Baer, A Aparasu (2007) Clinically important potential drug-drug interactions in outpatient settings. Res Social Adm Pharm 3(4): 426-437.

- Munir Pirmohamed, Sally James, Shaun Meakin, Chris Green, Andrew K Scott, et al. (2004) Adverse drug reactions as cause of admission to hospital: prospective analysis of 18 820 patients. Bmj 329(7456): 15-19.

- Matthijs L Becker, Marjon Kallewaard, Peter W J Caspers, Loes E Visser, Hubert G M Leufkens, et al. (2007) Hospitalisations and emergency department visits due to drug-drug interactions: a literature review. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 16(6): 641-651.

- Shobhana A (2019) Drug Interactions of Chronic Neuropsychiatric Drugs in Neuro-critical Care. Indian J Crit Care Med 23(Suppl 2): S157-S161.

- Smithburger PL, SL Kane-Gill, AL Seybert (2010) Drug-drug interactions in the medical intensive care unit: an assessment of frequency, severity and the medications involved. Int J Pharm Pract 20(6): 402-408.

- Kratz T, A Diefenbacher (2019) Psychopharmacological Treatment in Older People: Avoiding Drug Interactions and Polypharmacy. Dtsch Arztebl Int 116(29-30): 508-518.

- Unger M (2013) Pharmacokinetic drug interactions involving Ginkgo biloba. Drug Metab Rev 45(3): 353-385.

- Boyer EW, M Shannon (2005) The Serotonin Syndrome. New England Journal of Medicine 352(11): 1112-1120.

- de Leon J, E Spina (2018) Possible Pharmacodynamic and Pharmacokinetic Drug-Drug Interactions That Are Likely to Be Clinically Relevant and/or Frequent in Bipolar Disorder. Curr Psychiatry Rep 20(3): 17.

- Shafiekhani M, M Mirjalili, A Vazin (2018) Psychotropic drug therapy in patients in the intensive care unit - usage, adverse effects, and drug interactions: a review. Ther Clin Risk Manag 14: 1799-1812.

- Devlin JW, S Mallow-Corbett, RR Riker (2010) Adverse drug events associated with the use of analgesics, sedatives, and antipsychotics in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med 38(6 Suppl): S231-243.

- Cristiano S Moura, Nília M Prado, Najara O Belo, Francisco A Acurcio (2012) Evaluation of drug-drug interaction screening software combined with pharmacist intervention. Int J Clin Pharm 34(4): 547-552.

- Jan Wolff, Gudrun Hefner, Claus Normann, Klaus Kaier, Harald Binder, et al. (2021) Predicting the risk of drug-drug interactions in psychiatric hospitals: a retrospective longitudinal pharmacovigilance study. BMJ Open 11(4): e045276.

- J Wolff, P McCrone, L Koeser, C Normann, A Patel, et al. (2015) Cost drivers of inpatient mental health care: a systematic review. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci 24(1): 78-89.

- Colleen L Barry, Jonathan P Weiner, Klaus Lemke, Susan H Busch (2012) Risk adjustment in health insurance exchanges for individuals with mental illness. Am J Psychiatry 169(7): 704-709.

- Ellen Montz, Tim Layton, Alisa B Busch, Randall P Ellis, Sherri Rose, et al. (2016) Risk-Adjustment Simulation: Plans May Have Incentives to Distort Mental Health and Substance Use Coverage. Health Aff (Millwood) 35(6): 1022-1028.

- Wakefield JC (2007) The concept of mental disorder: diagnostic implications of harmful dysfunction analysis. World Psychiatry 6(3): 149-56.

- Ahmed Aboraya, Eric Rankin, Cheryl France, Ahmed El-Missiry, Collin John, et al. (2006) The Reliability of Psychiatric Diagnosis Revisited: The Clinician's Guide to Improve the Reliability of Psychiatric Diagnosis. Psychiatry (Edgmont) 3(1): 41-50.

- Jablensky A (2016) Psychiatric classifications: validity and utility. World Psychiatry 15(1): 26-31.

- Sara E Evans-Lacko, Manuela Jarrett, Paul McCrone, Graham Thornicroft (2018) Clinical pathways in psychiatry. The British Journal of Psychiatry 193(1): 4-5.

- Barbui C, M Tansella (2012) Guideline implementation in mental health: current status and future goals. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci 21(3): 227-229.

- Abdlekawy KS, AM Donia, F Elbarbry (2017) Effects of Grapefruit and Pomegranate Juices on the Pharmacokinetic Properties of Dapoxetine and Midazolam in Healthy Subjects. Eur J Drug Metab Pharmacokinet 42(3): 397-405.

- Khaled S Abdelkawy, Reham M Abdelaziz, Ahmed M Abdelmageed, Ahmed M Donia, Noha M El-Khodary, et al. (2020) Effects of Green Tea Extract on Atorvastatin Pharmacokinetics in Healthy Volunteers. European Journal of Drug Metabolism and Pharmacokinetics 45(3): 351-360.

- Khaled Sobhy Abdelkawy, Ahmed M Donia, Mahmoud S Abdallah (2015) Pharmacokinetics interaction of dapoxetine with different doses of green tea extract in male healthy volunteers using midazolam as CYP3A4 enzyme probe 5(12): 1-7.

-

Mohamed Y Abdelgaied, Khloud Shendy, Omar Abdelmagged, Naira Galal, Mai Tarek, Abdalla Essa, Amr Zakaria, Noran Eltabakh, Hind Bakloul, Khaled Abdelkawy and Michael G Zaki*. Common Neuropsychiatric Drug Interactions in Egypt That Require Clinical Interventions: A Retrospective Study in Delta Region. Arch Phar & Pharmacol Res. 4(2): 2024. APPR.MS.ID.000583.

-

Neuropsychiatric, Drug Interactions, Clinical Interventions, Delta Region, Lexicomp, Pharmacokinetic, Parkinson’s Disease

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.