Research Article

Research Article

Knowledge and Perception of Buruli Ulcer in Communities of Two Endemic Local Government Areas of Ogun State, Nigeria

Adeneye AK1*, Akinwale OP1, Ezeugwu SMC1, Olukosi YA1, Adewale B1, Sulyman MA1, Okwuzu J1, Mafe MA1, Gyang PV1, Soyinka FO2, Nwafor T1, Henry UE1, Musa BD1, Adelokiki AO2, Bisiriyu AH2 and Idowu FK2

1Nigerian Institute of Medical Resaerch, Yaba, Lagos, Nigeria

2Hansen Disease Centre and Ogun State Tuberculosis, Leprosy and Buruli Ulcer Control Programme, Abeokuta, Ogun State, Nigeria

Adeneye AK, Public Health and Epidemiology Department, Nigerian Institute of Medical Research, Lagos, Nigeria.

Received Date: August 12, 2022; Published Date: September 09, 2022

Abstract

Background: Buruli ulcer (BU) is a chronic debilitating disease caused by Mycobacterium ulcerans. It is one of the most neglected infectious diseases characterized by the development of painless open wounds. This study was conducted consequent to paucity of data on community knowledge and perception of BU in Nigeria.

Methods: This was a cross-sectional study of people’s knowledge and perception of Buruli ulcer in BU-endemic Yewa North and Yewa South local government areas (LGAs) of Ogun State, Nigeria using multi-stage sampling techniques. Data collection involved use of semi-structured questionnaire in a community survey alongside in-depth interviews and focus group discussions with community members. Secondary data were also collected through hospital records. There was also a laboratory component that involved collection of swabs from ulcers of individuals diagnosed of BU based on the clinical manifestations. The specimens collected were screened for the presence of acid fast bacilli (AFB) using standard methods. Confirmatory tests were done by applying the Ziehl-Neelsen Test and IS2404 polymerase chain reaction (PCR) methods. Quantitative and qualitative data collected were analysed using Textbase Beta and SPSS (version 20) softwares respectively.

Results: Epidemiological data on reported BU cases in study LGAs confirmed the existence of BU in the communities. All (100.0%) swab samples collected from the individuals clinically diagnosed of having BU were tested and confirmed to be active BU cases. In the community survey, a total of 236 consented respondents were interviewed with an average age of 33.1 years. Only 39.0% had a minimum of secondary education. A little over half (128; 54.2%) reported having knowledge of BU in their communities. However, only 35.6% adjudged BU a common disease in their communities while 56.0% perceived it as a serious health challenge. Few (14.0%) respondents had an average of one household member who had or have BU. Most (64.8%) did not know the cause of BU while 9.7% attributed it to witchcraft/Olobutu, bacteria (4.2%) and water contact (3.0%). 53.4% visit riverbanks for activities that were predominantly: washing (37.3%); swimming (35.7%); fetching water (19.8%); and agricultural activities (4.0%). Gender and age had no significant influence on respondents’ knowledge of the cause of BU (p>0.05).

Conclusion: Findings suggest the need for intensified public health education emphasising risk factors and actual cause of BU in the communities.

Keywords: Knowledge; Perception; Health seeking behaviour; Buruli ulcer; Nigeria

Introduction

Buruli ulcer (BU) is a chronic debilitating disease caused by infection with Mycobacterium ulcerans [1-3]. It is one of the most neglected but treatable tropical diseases [1,3]. The causative organism is from the family of bacteria which causes tuberculosis and leprosy but BU has received less attention than these diseases [4].

Infection leads to extensive destruction of skin and soft tissue with the formation of large ulcers usually on the legs or arms. Patients who are not treated early often suffer long-term functional disability such as restriction of joint movement as well as the obvious cosmetic problem. Early diagnosis and treatment are vital in preventing such disabilities [1,4,5]. Early diagnosis and treatment prevents 80% of such disabilities with 25% disability risk for late reporting [6].

Buruli ulcer frequently occurs near water bodies including slow flowing rivers, ponds, swamps, and lakes; cases have also occurred following flooding [4,7]. Activities that take place near water bodies, such as farming, and environmental factors such as deforestation and artificial topographic alterations are risk factors and wearing protective clothing reduce the risk of the disease. All ages and sexes are affected, but most patients are among age group of children under 15 years [1,4, 7-9]. In Africa, about 48% of those affected are children under 15 years, whereas in Australia, 10% are children under 15 years and in Japan, 19% are children under 15 years [1]. The disease can affect any part of the body, but in about 90% of cases the lesions are on the limbs, with nearly 60% of all lesions on the lower limbs [4]. The exact mode of transmission of BU remains unclear [2,4,10], but accruing data suggests that different modes of transmission occur in different geographic areas and epidemiological settings [10] with no evidence of it being transmitted from person to person [4]. The human-to-human transmission of BU was argued to be unlikely but negligible by Muleta AJ, et al. [2]. It mostly affects poor people in rural areas with limited access to health care Ayelo GA, et al. [9].

Buruli ulcer has been reported in over 33 countries with tropical, sub-tropical and temperate climates in Africa, South America and Western Pacific regions [1, 3, 5, 7] Of the 33 countries, only 14 regularly report data to the World Health Organisation (WHO) [3]. Estimated 5,000-6,000 cases are reported in actively reporting endemic countries worldwide [11]. The majority of cases are reported from West and Central Africa, including Benin, Cameroon, Côte d’Ivoire, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ghana and Togo [1, 12]. In recent years, Australia has been reporting a higher number of cases [1]. Increasing number of cases have been reported in Cameroon, Congo, Gabon, Sudan, Togo and Uganda [4]. The annual number of suspected BU cases reported globally was around 5000 cases up until 2010 when it started to decrease until 2016, reaching its minimum with 1,961 cases reported. Since then, the number of cases has started to rise again every year, up to 2,713 cases in 2018. In 2020, 1,258 BU cases were reported compared with 2,271 cases reported in 2019. The reduction in 2020 has been attributed to the impact of COVID-19 pandemic on active detection activities [3].

In Nigeria, after 30 years of no official report, an assessment carried out in south-eastern part of the country in November 2006 confirmed some BU cases [4]. Cases of BU have been reported across different parts of the country that include Adamawa, Benue, Cross River, Akwa Ibom, and Oyo States [8,13,14]. Most recently, the presence of Buruli ulcer in Nigeria was reported in Oyo, Anambra, Cross River, Enugu, Ebonyi and Ogun states where M. ulcerans strains were isolated from patients between year 2006 and 2012 [15, 16]. According to Marion, et al. [16], only 51 BU patients were described in 45 years, all found in Southern Nigeria. This was attributed to the lack of adequate public health structures dedicated to the diagnosis and treatment of BU and a control programme in the country until recently [9, 16]. In a report of a large cohort of 127 polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-confirmed Nigerian patients treated in neighbouring Republic of Benin, Marion, et al. [16] identified South Western Nigeria as an important endemic area for BU in the country.

Research gap identified in the determination of the exact prevalence and burden of the disease for reasons included: insufficient knowledge of the disease among both health workers and the general public, leading to significant under-reporting; people most affected by BU living in remote, rural areas with little contact with the health system; variability in the clinical presentation of the disease leading to BU being mistaken for other tropical skin diseases and ulcers; and BU not being a notifiable disease in many countries [4] including Nigeria [8].

Buruli ulcer is often diagnosed and treated based mainly on clinical findings by experienced health workers in endemic areas. Laboratory diagnoses are infrequently used to make decisions about treatment because of logistic and operational difficulties. However, laboratory diagnoses can be used to confirm the clinical diagnosis retrospectively on swabs and tissues taken during treatment, but this is seldom done. Four laboratory confirmatory methods commonly used are: direct smear examination; culture of M. ulcerans; polymerase chain reaction (PCR); and histopathology [1,4,5,17]. Bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccination appears to offer some short-term protection from the disease. Although the protection from BU is limited because there are currently no primary preventive measures that can be applied and there is no vaccine [1, 4].

Studies have shown that socio-cultural beliefs and practices strongly influence the health-seeking behaviours of people affected by BU. The first recourse is often traditional treatment [7]. In addition to the high cost of surgical treatment, fear of surgery and concerns about the resulting scars and possible amputations may also prevail. Due to the disfiguration, stigma is a problem that also prevents people from seeking treatment. Most patients consequently seek treatment too late, and both the direct and indirect costs are considerable. The impact of the disease on the few health facilities in the affected areas is enormous. The long hospital stay, often more than three months per patient, represents a huge loss in productivity for adult patients and family caregivers, and loss of educational opportunities for children [4]. The longterm care of those disabled, most of whom are children aged 15 years, places an additional costly burden on affected families [4, 7].

Buruli ulcer imposes a serious economic burden on affected households and on health systems that are involved in diagnosing the disease and treating patients. For example, in Ghana in 2001- 2003, the median annual total costs of treating BU to a household by stage of disease ranged from US$76.20 (16% of a work-year) per patient with a nodule to US$428 (89% of a work-year) per patient who had undergone amputation [4]. The average cost of treating a BU case was estimated to be US$780 per patient in 1994-1996, an amount which far exceeded per capita government spending on health. In Australia in 1997-1998, the average cost of diagnosing BU and treating a patient was AUS$14,608, an amount approximately seven times greater than the average national health expenditure per person (AUS$2,557). Early detection and treatment of BU are therefore economical and should be widely promoted [4].

In Nigeria, the systematic study of community knowledge and perception of BU vis-a-vis the modifiable risk factors for effective control of the disease have not been adequately conducted. It is consequent to paucity of data on community knowledge and perception of BU in Nigeria that this study was conducted to fill this knowledge gap.

Method

Study design

This was a cross-sectional study of the knowledge and perception of Buruli ulcer among people in the community.

Study locations

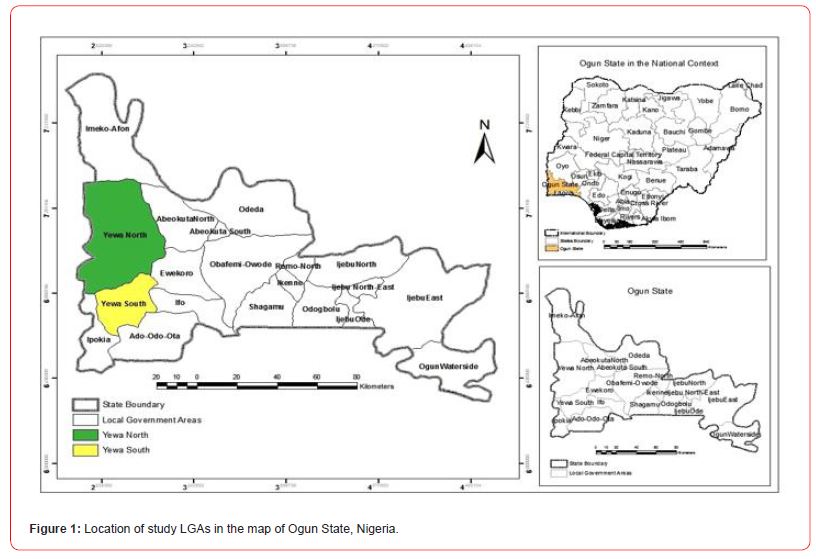

The study was carried out in two Buruli ulcer endemic local government areas (LGAs) in Ogun State, South West Nigeria. These LGAs included Yewa North and Yewa South (see Figure 1). Two communities were selected purposively in each of the two LGAs: Ebute Igbooro and Ijoun (Yewa North) and Idogo and Oke Odan (Yewa South).

Yewa North (formerly Egbado North) LGA in the west of Ogun State, Nigeria bordering the Republic of Benin has its headquarters in Aiyetoro and lies between latitude 7°09′N and longitude 2°55′E. It covers an area of 2,087 square km with a 2014 projected population of 241,420 people based on the 2006 National Population Census at 3.2% growth rate [18, 19]. Settlements in the Yewa North LGA include Aiyetoro, Oja-Odan, Ohunbe, Ikotun, Mosan, Ebute-Igbooro, Eggua, Ibese, Iboro, Sawonjo, Joga-Orile, Igan-Okoto, Igan Alade, Imasai, Igbogila, Idofio, Imeko and Obelle.

Yewa South (formerly Egbado South) LGA lies between latitude 6°48′N and longitude 2°57′E, and has its headquarters in Ilaro. Yewa South LGA has a 2014 projected population of 225,202 people based on the 2006 National Population Census at 3.2% growth rate [18, 19], and covers an area of 629 square kilometres. There are communities namely: Ilaro, Idogo, Iwoye, Oke Odan, Ijanna, Itoro, Owode, Erinja, Ajilete and Ilobi headed by Obas. The Yewa River with its immense tributaries is an important linkage that flows through the two LGAs to the Atlantic Ocean through Ado Odo LGA.

The people of the two LGAs in general and the study communities in particular have striking similarities in tradition, culture and economic activities. The inhabitants of the LGA are mainly Yoruba speaking with various dialects that include Yewa, Egun and Anago. The areas are noted for their agricultural products as most citizens are predominantly farmers and traders while others engage in artisanship. Most communities in both LGAs are rural and lack basic social amenities such as good roads, safe water supply, well equipped health centres as many of the inhabitants usually travel far to neighbouring communities such as the Centre de Diagnostic et de Traitement de l’Ulcere de Buruli in Pobe, Republic of Benin to seek medical attention because access to orthodox healthcare is minimal in the communities. Lack of basic amenities in many rural communities becomes serious social problem as inhabitants find it difficult to have access to good living. Nonetheless, there are public and private clinics, alternative health outlets as well as many patent medicine sellers (PMSs) abound in the two LGAs. Each community studied has a LGA health facility staffed primarily by Nursing Officers and Community Health Extension Workers. The LGAs have educational institutions ranging from primary to tertiary.

The two study communities, Ebute Igbooro and Ijoun with about 45,462 and 26,501 inhabitants respectively, in Yewa North LGA are located about 76km and 74km from Abeokuta, the State capital respectively while Idogo and Oke Odan with population of about 23,957 and 42,241 respectively in Yewa South LGA are located 49km and 72km from Abeokuta, the State capital respectively. The study communities are rural and riverine.

Study population

The target populations for this study were men and women in BU endemic communities of the selected LGAs.

Sampling procedure

The respondents were selected using a multi-stage sampling technique. This involved the combination of purposive, systematic, simple random and convenience sampling methods [20, 21]. The first stage of sampling involved a purposive selection of the State and thereafter (second stage) two LGAs from the list of 20 LGAs in the State were purposively selected given reported cases of BU [8]. The third stage of the sampling process involved the adoption of the simple random sampling method in selecting two communities in each of the selected LGAs. Subsequently, a systematic sampling of houses was carried out after which respondents were randomly selected from the selected houses.

Further, convenience sampling method was used in selecting some diagnosed BU patients based on clinical signs seen during visits to Primary Healthcare Centres. A few others were found and visited in their homes through case search using snowballing method with the guide of community contacts who knew people having the clinical manifestations similar to BU in the communities.

Data Collection

Community survey

Data collection for the study involved the use of both qualitative and quantitative procedures. The qualitative data collection involved in-depth interviews (IDIs) and focus group discussions (FGDs) with community members. The quantitative aspect of the data collection involved the use of semi-structured questionnaire in community survey among men and women in the communities. Prior to the main study, the data collection tools and procedures designed for data collection in the study were pre-tested for content validation in Eggua, a rural community in Yewa North LGA with similar socio-demographic characteristics with the communities where the study was actually conducted.

Information, Education and Communication (IEC) materials in pictorial form including flyers and posters depicting basic concepts and signs about BU obtained from the State Focal Person on BU Control Programme were used during the questionnaire administration, FGDs and IDIs in order to aid their understanding of the questions asked.

A total of 236 respondents were interviewed during the community survey in selected communities. A total of six FGD sessions (3 male groups vs. 3 female groups) were conducted in the study LGAs (three per LGA). Each FGD session was held in a comfortable neutral setting, and consisted of a moderator, a note taker and 9 to 10 participants of the same sex with similar social background. A total of 58 participants comprising of 30 males and 28 females participated in the discussions. The FGD sessions were recorded using digital audio recorder and moderated in the local language, Yoruba. Complementary to the FGD sessions were a total of 8 IDIs (four per LGA) conducted with two community leaders, six adults in the communities (three males and three females) respectively. The respondents in the community survey and IDIs were engaged in local and English languages as appropriate.

In addition to the community survey, there was a laboratory component that involved collection of swabs from ulcers of individuals diagnosed of BU based on the clinical manifestations (see Figure 2) for examination and confirmation in the laboratory. This was carried out on those who volunteered to participate in the study following obtaining their written informed consent. The laboratory investigation was carried out by Medical Laboratory Scientists trained on BU identification. The Ogun State Tuberculosis, Leprosy and BU Control Programme accredited laboratory at the State Hospital, Ilaro and Hansen Disease Centres, Abeokuta were collaborated with in this regard.

Case finding and laboratory confirmation

All the 7 individuals with a diagnosis of BU based on their clinical manifestation of the BU signs which most prominently is ulcer were considered for inclusion as cases. Two swab specimens were collected from the undermine edges of ulcers of the consented individuals while fine needle aspiration (FNA) specimens were collected from those having ulcer without undermine edges. The specimens were screened for the presence of acid-fast bacilli (AFB) using standard methods. Confirmatory diagnostic tests were done by applying the Ziehl-Neelsen Test [22] and IS2404 polymerase chain reaction (PCR) methods [23, 24] to the collected swab samples. The World Health Organisation [25, 26] recommends two laboratory tests to confirm a diagnosis of BU. However, in endemic settings, one may consider one positive test result from PCR or microscopy appropriate for the confirmation of clinical diagnosis because of the high positive predictive values for PCR (100%) and microscopy (97%) [25, 26]. While the Ziehl-Neelsen Test was carried out at the TB Laboratory of the Hansen Clinic, Abeokuta, the samples for PCR analysis were sent for confirmation at the Mycobacteriology Unit, Department of Microbiology, Institute of Tropical Medicine, Antwerp, Belgium.

Data analysis

Data from completed questionnaires from the community survey were coded and entered into the computer. Descriptive statistics were used to describe the quantitative data. The quantitative data were analysed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 20.0 software. The data were further analysed to generate frequency tables as well as cross-tabulation of the knowledge and perception of BU mentioned by LGA. Tabulations, descriptive statistics and non-parametric tests were the major data analytic procedures that were used. Pearson’s Chi square test was used for tests of significance of association between relevant dependent and independent variables and P value of <0.05 accepted as significant. A pooled data from the two communities in each LGA were used to examine the knowledge and perception of BU mentioned by the respondents.

The qualitative data from the FGDs and IDIs were analysed using the textual analysis programme, Textbase Beta, developed by Bo Summerlund and distributed by Qualitative Research Management of Desert Hot Springs, California, Textbase Beta software [27, 28].

Ethical issues

The study was conducted under universal ethical principles guiding research. The informed consent of the participants was obtained before enlisting them into the study for tissue collection and interview. In the case of children, consent was obtained from their parents. The participants were informed of possible benefits, discomforts/inconveniences, risks involved and assured of confidentiality of information divulged for the purpose of the study. Ethical approval for the research protocol for the study with assigned reference number IRB/14/279 was obtained from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the Nigerian Institute of Medical Research, Lagos. Approvals at the State and local government, and community levels were also obtained prior to the conduct of the study.

Results

Epidemiological data on reported BU cases in study LGAs

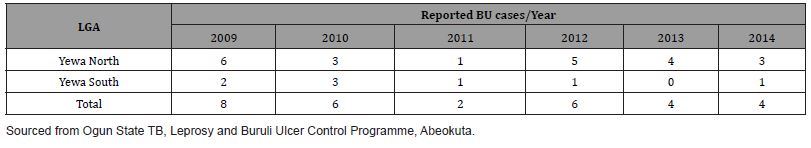

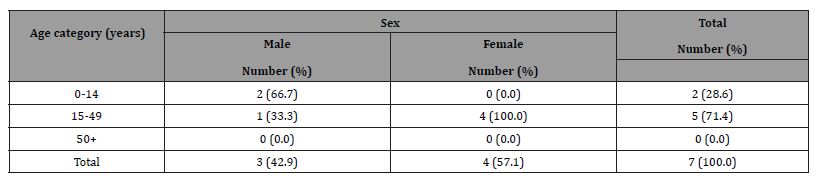

Secondary data from the study confirmed the existence of BU in the communities as illustrated in Table 1.

A total of 7 diagnosed BU cases based on clinical signs comprising of 5 cases (3 males vs. 2 females) seen during visits to Primary Healthcare Centres and two cases (2 females) aged between 7 and 40 years found through case search using snowballing method with the guide of community contacts who knew people having the clinical manifestations similar to BU in the communities. Table 2 shows the age distribution of observed BU cases.

Table 1: Reported cases of BU in communities of study LGAs 2009-2014.

Table 2: Age distribution of individuals observed Buruli ulcer cases.

Figures 3a-c show some observed suspected BU cases in the study communities as captured by the research team. All (7/7,100.0%) swab samples collected from the individuals clinically diagnosed of having BU were confirmed in the laboratory to be active BU cases.

Background characteristics of respondents

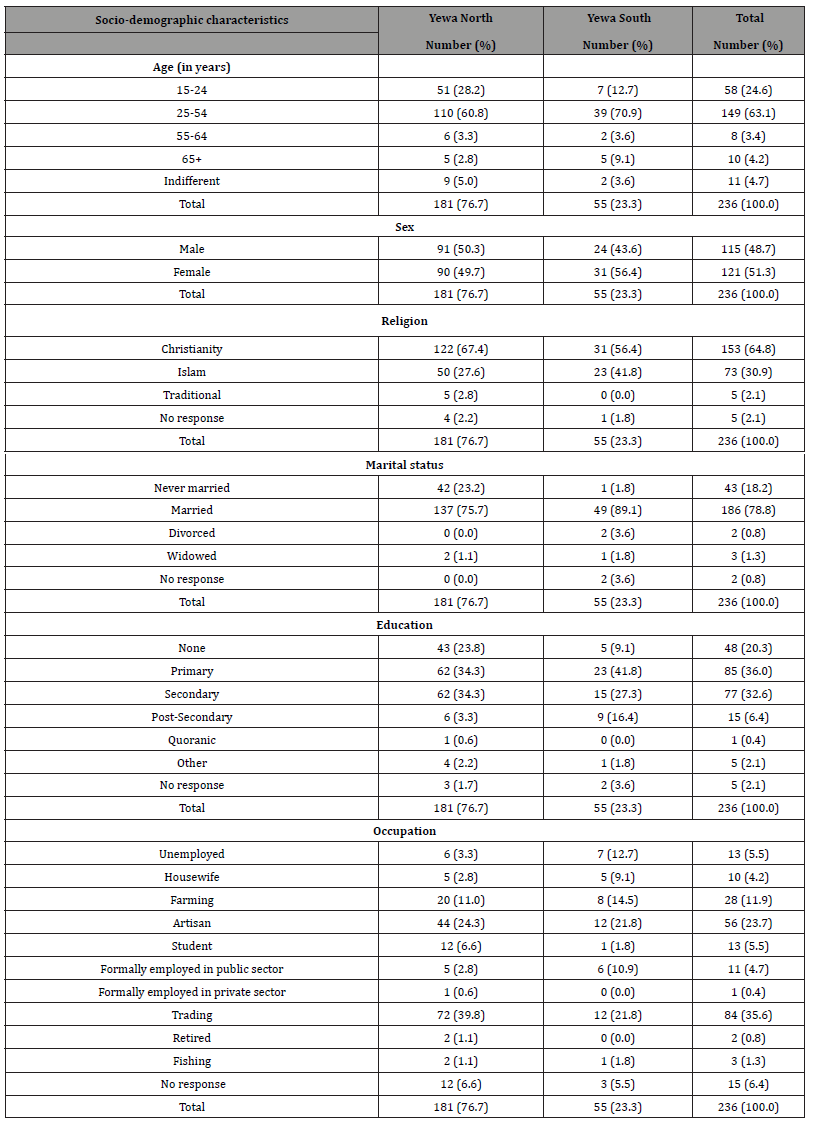

A total of 236 consented respondents were interviewed (Yewa North 76.7% vs. Yewa South 23.3%; males 48.7% vs. females 51.3%). Their ages ranged from 19 to 87 years with an average age of 33.1 years and median age of 30 years. Most (88.9%) were married. High level of literacy was reported among the respondents with 75.0% having minimum of primary education. Most respondents were artisans (36.1%) and traders (33.3%). The respondents’ incomes per month ranged from N1,000.00 (US$2.41) to N80,000.00 (US$192.68) with a mean monthly income of N15,866.85 (US$38.21) and a median monthly income of 10,000.00 (US$28.08). Table 3 shows the socio-demographic characteristics of the respondents. [Note: N451.20 = US$1.00]

Table 3: Socio-demographic characteristics of respondents.

Knowledge of Buruli ulcer among respondents

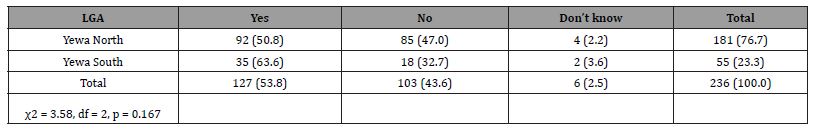

(Table 4 shows) that a little over half (53.8%) [Yewa North 50.8% vs. Yewa South 63.6%] of respondents admitted knowing that BU cases exist in their communities while others (43.6%) claimed there were no cases in their communities. There was no significant difference in the knowledge of BU cases among respondents in the communities by LGA (p>0.05).

Table 4: Knowledge of cases of BU in the communities among respondents.

On their knowledge of how common the incidence of BU cases is in their communities, only 35.6% adjudged BU as a common disease in their communities and 64.4% did not. Knowledge of the age categories of people mostly affected by BU among the respondents showed that a larger number (40.7%) affirmed that BU affects people of all ages regardless of gender. Others pointed out that BU mostly affects those aged: 30 year and above (14.4%); 11-19 years (6.8%); 20-29 years (5.1%); and less than or equal to 10 years (4.7%). On the contrary, virtually all (100%) of the FGD participants and those interviewed were of the view that BU affects people of all ages in their communities regardless of gender.

When asked if any member of their households or any other person in their community had any signs of BU at least two weeks to the survey, only 33 (14.0%) of 236 respondents were affirmative. The number of those known to have any signs of BU at least two weeks to the survey ranged from 1 to 4 with an a mean of 2±1. Those known to have BU by the respondents were their: siblings (30.3%); friends and neighbours (21.2%); other relations (18.2%); spouses (15.2%); children (9.1%); and parents (6.1%).

Cumulative responses on which part of the body mostly affected among those known to have had or is having BU were: arms only (10.2%); legs/thighs (43.2%); both arms and legs/thighs (25.0%); trunk (chest and back) (5.1%); and all parts of the body (17.4%).

Only a little above one-third (38.2%) of respondents correctly knew the manifestations of ulcers (19.1%), nodules (17.8%) and deformities of the arm and or leg (1.3%) as the signs of BU. Results showed that about half (50.4%) did not know the signs of BU while 11.4% did not respond. Chi Square test showed that respondents’ LGA of residence had significant correlation with their knowledge of signs of BU (34.3% Yewa North vs. 45.5% Yewa South) (χ2 = 25.1, df = 4, p = 0.000). On the contrary, there was no gender difference in the respondents’ knowledge of the signs of BU (χ2 = 5.75, df = 4, p = 0.219).

When the respondents were probed on the local name for BU in their communities, the local names mentioned were Olobutu (31.4%) and Egbo adaijina (25.8%). While some (35.6%) respondents claimed not to know the local name for BU, others (7.2%) were indifferent. Similarly, when the FGD participants and those interviewed were asked to mention the local name for BU in their communities, most participants and interviewees regardless of gender overwhelmingly stated that BU is called Olobutu in local language compared to a very few who mentioned Egbo adaijina. It was explained that Olobutu is a personified spirit believed to afflict people with BU which could be consequent to witchcraft or evil machination from ones enemies.

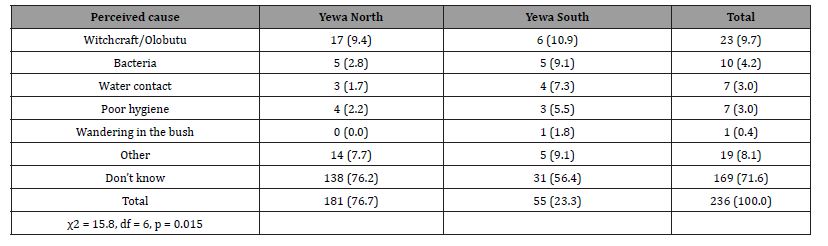

Most (71.6%) did not know the cause of BU while 9.7% attributed it to witchcraft/Olobutu, bacteria (4.2%), water contact (3.0%) and poor hygiene (3.0%). Table 5 presents the respondents’ knowledge on the cause of BU by LGA. Statistical test showed that respondents’ knowledge of the cause of BU was significantly related to their LGA (p<0.05). Gender (χ2 = 3.43, df = 8, p = 0.905) and age (χ2 = 28.88, df = 40, p = 0.904) had no significant influence on respondents’ knowledge of the cause of BU.

Table 5: Respondents’ knowledge of the cause of BU by LGA distribution.

Perception of Buruli ulcer among respondents

Perceived seriousness of BU in the communities showed that of the 236 respondents interviewed, a large number (55.9%) perceived it as a serious health challenge while 23.3% did not perceived the infection as serious and few (20.8%) were indifferent. The FGDs and IDIs among the men and women in the communities showed their consensus about the perceived seriousness of BU. Gender (χ2 = 1.96, df = 2, p = 0.376) and LGA of residence (χ2 = 1.98, df = 2, p = 0.172) had no significant influence on respondents’ perceived seriousness of BU.

A community leader interviewed in Ebute Igbooro in Yewa North LGA explained that, “…many years ago, people used to die as a result of the disease. We didn’t know it was caused by bacteria but many of us now know better. The disease was believed to be afflicted on people by their enemies through witchcraft.”

Different health care options available for Buruli ulcer treatment and health seeking behaviour of the people in the communities

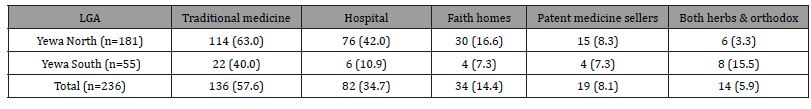

The most preferred treatment options usually sought for BU in the study communities as mentioned by the respondents included traditional medicine (57.6%), going to hospital (35.2%) while a few (5.9%) combined both. Table 6 illustrates the health-seeking behaviour on BU treatment in the communities.

Table 6: Preferred treatment options for BU in the communities according to LGA..

Those in Yewa North LGA are more likely to seek treatment at the hospital when infected with BU than those in Yewa South LGA (χ2 = 19.58, df = 1, p = 0.00). Further statistical analysis showed that those infected with BU are more likely to seek treatment from either traditional healers or hospitals or both in the two LGAs (χ2 = 3.43, df = 8, p = 0.905).

When asked what people usually do when they or their children have BU, a large number of the FGD participants reported that most individuals having BU usually travel far to a hospital in adjoining communities in neighbouring Republic of Benin for treatment. Other actions people were mentioned to usually take when infected with BU were: self-treatment at home, which varied from cooking and drinking herbal remedies prepared from leaves, roots and barks of some specified trees (agbo) freely obtained from the home environment or bought from herbalists in the market based on advice from relations; visiting a traditional healer to praying. A male FGD participant in Ebute Igbooro in Yewa North LGA revealed that, “…people travel to well-established hospitals in neighbouring Republic of Benin where patients can be admitted, treated free of charge and children placed on educational programme while on admission.” Another male FGD participant in Idogo, Yewa South LGA in contrast explained that, “…some people resort to seeking care for Olobutu (Buruli ulcer) from traditional healers rather than visiting the hospital because of the unaffordable cost of travelling to Republic of Benin to access free treatment, the long hospital stay, fear of surgery and concerns about possible amputations.”

Practices relating to water usage among respondents

Sources of water for different household uses mentioned by respondents surveyed included: well (53.0%); river (41.5); pipeborne water (32.4%); stream (12.3%); rain water (3.8%); spring (2,1%); and other such as pond (1.3%).

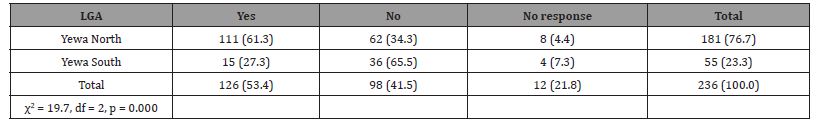

One hundred and twenty-six (53.4%) respondents reported going to ponds, riverbanks and other water bodies in their communities for activities that were predominantly: washing (37.3%) (see Figure 4); swimming (35.7%); fetching water (19.8%); and agricultural activities (4.0%). On the contrary, 41.5% claimed not going to any of the streams or rivers and 5.1% were indifferent. The statistical test results of a chi square contingency table showed that respondents’ probability of visiting riverbanks and other water bodies which are likely places where BU can be contracted had significant correlation with their LGA of residence as more of those in Yewa North LGA (61.3%) tend to visit such likely places where BU can be found than those from Yewa South LGA (27.3%) (Table 7).

Table 7: Response on visit to ponds, riverbanks, and other water bodies in the communities according to LGA.

Statistical test further showed no gender difference in the respondents’ propensity to go to the stream or river as more males than females are more likely to go to the stream or river (57.4% males vs. 49.6% females) (χ2 = 5.63, df = 2, p = 0.060).

Swimming and other activities among respondents during visits to the river banks and other water bodies which are likely places where BU can be found had no significant correlation with report of BU cases in their households (χ2 = 8.42, df = 4, p = 0.077).

Control measures being taken to reduce the burden of BU in the communities

Of the 236 respondents surveyed, only 21 (8.9%) knew control measure(s) being taken to reduce the burden of BU in their communities while most (42.4%) responded “don’t know”, 29.2% emphatically stated that “nothing” was being done in this regard and others (19.5%) did not respond. All (100.0%) of the few who responded knowing the control measures being taken to reduce the burden of BU in their communities mentioned continuous public health education in their communities. Statistical test showed gender difference in the respondents’ knowledge of BU control efforts in their community as more males than females are more likely to know such control measure(s) (45.2% males vs. 31.4% females) (χ2 = 9.18, df = 3, p = 0.027). Similarly, LGA of residence had significant correlation with respondents’ knowledge of BU control efforts in their community (χ2 = 30.7, df = 3, p = 0.000).

Discussion

This study shows that about one of every 10 respondents knew someone around their homes who had clinical signs of BU at the time of the survey. This confirms that BU exists in communities of the two LGAs studied and may be more prevalent than had been previously thought as buttressed by Ayelo, et al. [9] and Otuh, et al. [12]. This finding demonstrates that BU has not disappeared from Nigeria as emphasized by Chukwuekezie, et al. [10].

Our sample of cases mirrored the converse sex distribution from other studies. Other studies conducted in Ghana for example, have demonstrated a predominance of males among children aged less than 20 years of age with BU compared to more females reported among adult cases (>20 years of age) [29, 30]. However, the age distribution of those affected in this study in Table 2 contrasts the pattern reported by World Health Organisation [1] that about 48% of those affected in Africa are children under 15 years.

Pervasive knowledge of incidences of BU cases and high perceived seriousness of the disease in the study communities exist, with traces of denial and misconceptions of its cause. The manifestation of high knowledge of incidences of BU cases is encouraging. This encouraging scenario could be used as a platform to launch more community education programmes and case detection strategies in the communities studied. The fact that almost half of the population studied either had low perceived seriousness of BU as a serious health problem or were indifferent to it in the communities is of high concern. The people need to know the disease is serious and can be effectively prevented and is also treatable if detected and diagnosed early.

Denial of the existence of BU in the communities studied by many of the respondents in the community survey is probably attributable to social stigma attached to BU in the communities. Stigma attributable to the disfiguration caused by BU is a problem that also prevents people from seeking treatment. Consequently, most patients seek treatment too late as reported by World Health Organisation [4].

Recourse to traditional and faith-based treatment as preferred treatment options for BU in the communities as reported by most respondents in the study is perhaps attributable to socio-cultural beliefs about the cause of BU which could have influenced their health-seeking behaviours as evident in Table 5 and Figure 3a. It is evident from Table 5 that traditional treatment is often the first recourse as reported by World Health Organisation [4].

Incidentally, the study communities have a good complement of traditional practitioners who perpetuate different traditional or herbal practices which are most likely cheap and will compete with the orthodox medical practitioners. Given the proximity of people most affected by BU in remote rural areas such as the study communities with little or no contact with the health system, the people are left with no option but to patronise the traditional practitioners.

The difficulty of accessing prompt and appropriate healthcare services by many of the inhabitants due to proximity to health clinics in the study areas is a factor that probably encourages many to usually travel far to adjoining communities in neighbouring Republic of Benin to seek medical attention particularly for BU.

Only very few respondents were found to have had correct knowledge of BU as a bacterial infection that is related to environmental factors with many expressing numerous misconceptions about the cause of BU as illustrated in Table 5. Insufficient knowledge of BU demonstrated among the population studied increases the likelihood of significant under-reporting judging by results in Table 2.

Given the reported cases of BU in the LGAs between 2009 and 2014 in Table 1 corroborated by Otuh PI, et al. [12], the actual burden of the disease is difficult to establish perhaps due to underreporting of cases not captured due to high patronage of traditional practitioners who are not integral part of the formal health system through which notifiable diseases such as BU could be captured.

It is disappointing that only a few respondents in the study knew BU is related to environmental factors as evident in Table 5. This is critical knowing that epidemiological studies [13, 31-33] have established a connection of BU with water because use of a river or pond has consistently been identified as a risk factor particularly as some studies have found an increased risk of infection associated with wading in water [34, 35] and that the primary risk factor for M. ulcerans infection seems to be living in proximity to a body of water [36].

Given that the exact mode of transmission of BU remains unclear, but accruing data suggests that different modes of transmission occur in different geographic areas and epidemiological settings [10] and that protection against BU is limited because there are currently no primary preventive measures that can be applied and there is no vaccine as emphasized by World Health Organisation [1], considerable continuous awareness of the disease therefore needs to be created and strengthened to help improve public understanding of the disease with emphasis on the cause, clinical features, risk factors that could predispose people to the infection, and appropriate treatment available. This can be achieved through regular distribution of information, education and communication/ behaviour change and communication (IEC/BCC) materials such as posters, handbills and leaflets with messages and visual illustrations about BU as well as showing documentaries using audio-visual aids. Such health education package should target more of males aged 0-14 years and those aged 15-49 years as well as women aged 15-49 years.

In view of radio being reported by World Health Organisation [37] as an important medium for receiving health information and that radio programmes have the advantage of being accessible to all family members, it becomes imperative that this medium of communication is adequately used and through which the information relating to BU can be shared, referred to and discussed upon as a means of creating and increasing awareness among the teeming listening population in Ogun State in general and the study LGAs in particular. We therefore suggest the use of the radio channels in the State for the dissemination of the information promoting BU targeting the studied LGAs. Similarly, schools, markets and religious places could serve as complementary effective channels for public health education.

Knowing that early diagnosis and effective treatment is vital in preventing disabilities attributable to BU as reported by de Souza, et al. [5] and World Health Organisation [1,4] depend on early detection of cases at the community level as a cornerstone of the World Health Organisation Buruli ulcer control strategy emphasized by World Health Organisation WHO [1], active surveillance of the disease as part of control activities in the Tuberculosis and Leprosy Control Programme particularly at the LGA level as it is the case in Nigeria has to be enhanced and strengthened. The need for training and re-training of health personnel Kooli C and Al Muftah H [38] including village health workers particularly at the LGA level in Ogun State also becomes imperative in this regard. This is important because training practitioners to improve their knowledge and skills through various forms such as the dissemination of clinical guidelines, training sessions, small group meetings and oneto- one detailing is a commonly used strategy to improve case management behaviour [39]. Other strategic option of achieving early detection of cases in addition to training of health workers is the engagement of volunteers to be identified and recruited by the BU focal persons in collaboration with local communities who could be trained as BU community surveillance agents for detecting, reporting, responding to and monitoring cases just as “Role Model Mothers” were successfully used in the implementation of early and appropriate home management of malaria in the country [40, 41]. Training topics including the causes of BU, its clinical features, diagnosis, the importance of prompt treatment, significance and indications for referral, preventive advice and IEC/BCC materials, and strategies to disseminate information about BU within the community are suggested should be incorporated in the training modules of such training programme. It is believed that this will curb morbidity from BU in the communities. We also believe that capacity building for health workers particularly those operating in areas in which the disease is endemic will allow effective use of tools for capturing data on BU as a notifiable disease that feed into the country’s Integrated Disease Surveillance and Response (IDSR) database of the national surveillance system. At the same time, it is expected that this will contribute to increasing the case-detection rate of non-ulcerative forms as targeted in the report of the National Tuberculosis and Leprosy Control Programme [42].

It is disappointing that none of the health facilities visited during the study had any treatment guidelines document on BU as at the time of the study as it exists in control programmes for other diseases such as tuberculosis [43] and malaria [44, 45]. This perhaps confirms World Health Organisation [4] assertion that BU has received less attention than tuberculosis and leprosy despite the fact that the causative organism which causes these diseases is from the same family of bacteria. It is important that such prevention, diagnosis and treatment guidelines for BU need to be developed, printed and distributed as part of control activities in the Tuberculosis and Leprosy Control Programme to health facilities at all the levels of health care in the country particularly at the primary health care level.

It was intuitively plausible that most respondents reported that nothing is being done for BU control in the communities. This is not surprising considering its description as one of the most neglected but treatable tropical diseases [4]. Key stakeholders within these local communities thus need to be made to realize that it is imperative that they transform from passive recipients into active participants of health care programmes.

There are currently no primary preventive measures that can be applied against BU and there is no vaccine developed against the disease yet. Given that the BCG vaccination primarily given to children after birth to prevent TB as part of the national immunisation schedule for children in the country documented to offer some short-term protection from BU, ensuring complete coverage of BCG vaccination in all children after birth in affected rural areas could be useful in reducing the burden as emphasized by Walsh DS, et al. [7].

Results from the study highlight the importance of taking cognisance of the need to develop strategies of expanding access to adequate, affordable and quality treatment for people affected by BU in the studied LGAs. Health facilities in the LGAs need to be equipped with adequately trained personnel and equipment for appropriate diagnosis and effective treatment of BU particularly at the primary health care level most importantly now that rapid diagnosis of Buruli ulcer is now possible at district-level health facilities according to World Health Organisation [11,38,46].

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study shows that pervasive knowledge of BU cases and high perceived seriousness of the disease in the study communities exist, though with traces of denial of its existence and misconceptions of its actual cause. Nonetheless, there is need for more public health education designed and developed to emphasise and address common modifiable risk factors including people’s knowledge, perception, health seeking behaviour as well as practices that make them vulnerable to BU in the studied LGAs. Overall, the results provide insights for BU programme planning and operationalisation in the affected LGAs. This report supports the establishment of BU treatment centre(s) and the capacity building of health workers in the studied LGAs and other BU endemic areas in the country at large.

Acknowledgement

Funds for this study were provided by the Nigerian Institute of Medical Research. We gratefully acknowledge the support and cooperation of the Health Department of Yewa North and Yewa South LGA. We also appreciate the assistance of Mr. Joseph Ibitokun, Mrs Theresa Funke Popoola, Mrs Funmilayo Fagbemi, Abigael Oluwadamilola Afolabi, Rebecca A. Faleru, Mrs Comfort A.O. Adedokun, Ali Mohammed, Mr. Aileru Amisu ayinde, Mrs. A.K. Adetona, Mr. Olaleye Olawole, Rukayat Olaniyan, Yemisi Oladayo, Mr. Adebiyi Seun Aremu and Mr. Ladipo Ebenezer Adedayo in data collection. Profound gratitude of the team goes to Mr. Abiodun Olakiigbe (Monitoring and Evaluation Unit, NIMR) who helped with the data analysis and Mubarak Lasisi of the Department of Urban and Regional Planning, Faculty of Environmental De¬sign and Management, University of Ibadan, who assisted with the map.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest.

References

- World Health Organisation (2017) Buruli ulcer. Geneva: World Health Organisation.

- Muleta AJ, Lappan R, Stinear TP, Greening C (2021) Understanding the transmission of Mycobacterium ulcerans: A step towards controlling Buruli ulcer. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 15(8): e0009678.

- World Health Organisation (2021) Buruli ulcer (Mycobacterium ulcerans infection). Geneva: World Health Organisation.

- World Health Organisation (2007) Buruli ulcer disease (Mycobacterium ulcerans infection). Geneva: World Health Organisation, (Fact sheet Number 199).

- De Souza DK, Quaye C, Mosi L, Addo P, Boakye DA. (2012) A quick and cost effective method for the diagnosis of Mycobacterium ulcerans infection. BMC Infect Dis 12: 8.

- World Health Organisation (July 2, 2016) Buruli ulcer. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2015.

- Walsh DS, Portaels F, Meyers WM (2008) Buruli ulcer (Mycobacterium ulcerans infection). Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 102(10): 969-978.

- Johnson PDR, Stinear T, Small PLC, Pluschke G, Merritt RW, et al. (2005) Buruli ulcer (M. ulcerans infection): new insights, new hope for disease control. PLoS Med 2(4): e108.

- Ayelo GA, Anagonou E, Wadagni AC, Barogui YT, Dossou AD, et al. (2018) Report of a series of 82 cases of Buruli ulcer from Nigeria treated in Benin, from 2006 to 2016. PloS Negl Trop Dis 12(3): e0006358.

- Chukwuekezie O, Ampadu E, Sopoh G, Dossou A, Tiendrebeogo A, et al. (2007) Buruli ulcer in Nigeria. Emerg Infect Dis 13(5): 782-783.

- World Health Organisation. (2015) Rapid diagnosis of Buruli ulcer now possible at district-level health facilities. Geneva: World Health Organisation.

- Otuh PI, Soyinka FO, Ogunro BN, Akinseye V, Nwezza EE, et al. (2018) Perception and incidence of Buruli ulcer in Ogun State, South West Nigeria: intensive epidemiological survey and public health intervention recommended. Pan Afr Med J 29(166): 1-9.

- Oluwasanmi JO, Solanke TF, Olurin EO, Itayemi SO, Alabi GO, et al. (1976) Mycobacterium ulcerans (Buruli) skin ulceration in Nigeria. Am J Trop Med Hyg 25(1): 122-128.

- Janssens PG, Pattyn SR, Meyers WM, Portaels F (2005) Buruli ulcer: an historical overview with updating to 2005. Bulletin des Séances. Académie Royale des Sciences d'Outre-Mer 51: 165-199.

- Vandelannoote K, Jordaens K, Bomans P, Leirs H, Durnez L, et al. (2014) Insertion sequence element single nucleotide polymorphism typing provides insights into the population structure and evolution of Mycobacterium ulcerans across Africa Appl Environ Microbiol 80(3): 1197-1209.

- Marion E, Carolan K, Adeye A, Kempf M, Chauty A, et al. (2015) Buruli Ulcer in south western Nigeria: a retrospective cohort study of patients treated in Benin. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 9(1): e3443.

- Yeboah-Manu D, Asante-Poku A, Asan-Ampah K, Ampadu ED, Pluschke G (2011) Combining PCR with microscopy to reduce costs of laboratory diagnosis of Buruli ulcer. Am J Trop Med Hyg 85(5): 900-904.

- National Bureau of Statistics. Annual abstract of statistics 2009: Federal Republic of Nigeria. Abuja: National Bureau of Statistics, 2009.

- National Population Commission. 2006 population and housing census of the Federal Republic of Nigeria: Housing characteristics and amenities tables–priority tables (LGA). Abuja: National Population Commission, 2010. volume 2. NPC/CENSUS 2006/PT/VOLUME II

- Neuman WL (1994) Social research methods: qualitative and quantitative approaches. Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

- Moser CA, Kalton G (1997) Survey methods in social investigation. Aldershot: Dartmouth Publishing Company.

- Hayman JA (1993) Mycobacterium ulcerans infections-the Buruli or Bairnsdale ulcer. Tropical Medicine and Surgery 64: 358-360.

- Ross BC, Marino L, Oppedisano F, Edwards R, Robins-Browne RM, et al. (1997) Development of a PCR assay for rapid diagnosis of Mycobacterium ulcerans infection. J Clin Microbiol 35 (7): 1696-1700.

- Stienstra Y, van der Werf TS, Guarner J, Raghunathan PL, Spotts Whitney EA, et al. (2003) Analysis of an IS2404-based nested PCR for diagnosis of Buruli ulcer disease in regions of Ghana where the disease is endemic. J Clin Microbiol 41 (2): 794-797.

- World Health Organisation. (2008) Buruli ulcer: progress report 2004-2008. Geneva: World Health Organisation. Weekly Epidemiological Record 83(17): 145-154.

- World Health Organisation (2008) Meeting of the WHO Technical Advisory Group on Buruli ulcer. Geneva: World Health Organisation.

- Miles MB, Huberman AM (1994) Qualitative data analysis: an expanded sourcebook (2nd), London: Sage Publications.

- Fielding NG, Lee RM (1998) Computer analysis and qualitative research. London: Sage Publications.

- Amofah GK, Bonsu F, Tetteh C, Okrah J, Asamoa K, et al. (2002) Buruli ulcer in Ghana: results of a national case search. Emerg Infect Dis 8(2): 167-170.

- Aiga H, Amano T, Cairncross S, Domako JA, Nanas O, et al. (2004) Assessing water-related risk factors for Buruli ulcer: a case-control study in Ghana. Am J Trop Med Hyg 71(4): 387-392.

- The Uganda Buruli Group, Epidemiology of Mycobacterium ulcerans infection (Buruli ulcer) at Kinyara, Uganda. (1971) Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 65(6): 763-775.

- Barker DJP (1973) Epidemiology of Mycobacterium ulcerans infection. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 67(1): 43-47.

- Marston BJ, Diallo MO, Horsburgh Jr CR. Diomande I, Saki MZ, et al. (1995) Emergence of Buruli ulcer disease in the Daloa region of Côte d’Ivore. Am J Trop Med Hyg 52(3): 219-224.

- Raghunathan PL, Whitney EA, Asamoa K, Stienstra Y, Taylor Jr TH, et al. (2005) Risk factors for Buruli ulcer disease (Mycobacterium ulcerans infection): results from a case–control study in Ghana. Clin Infect Dis 40(10):1445-1453.

- Pouillot R, Matias G, Wondjie C, Portaels F, Valin N, et al. (2007) Risk factors for Buruli ulcer: a case control study in Cameroon. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 1(3): e101.

- Jacobsen KH, Padgett JJ (2010) Risk factors for Mycobacterium ulcerans infection. Int J Infect Dis 14(8): e677-e681.

- World Health Organization. (1995) Towards the healthy women counselling guide. Geneva: World Health Organisation. TDR/GEN/95.1

- Kooli C, Al Muftah H (2022) Artificial intelligence in healthcare: a comprehensive review of its ethical concerns. Technological Sustainability 1-11.

- World Health Organisation. (2006) Partnerships for malaria control: engaging the formal and informal private sectors. Geneva: World Health Organisation (TDR/GEN/06.1).

- Ajayi IO, Kale OO, Oladepo O, Bamgboye EA (2007) Using “mother trainers” for malaria control: the Nigerian experience. Int Q Community Health Educ 27(4): 351-369.

- Nwankwo LO, Nwaiwu O, Ezeora AC, Onnoghen N (2014) A role model mother/caregiver programme to expand home-based management of malaria with artemether-lumefantrine in Nigeria. Nigerian Medical Practitioner 65(5-6): 69-74.

- National Tuberculosis and Leprosy Control Programme [Federal Ministry of Health, Nigeria]. Annual report - 2008. 2009. Abuja: National Tuberculosis and Leprosy Control Programme, Department of Public Health, Federal Ministry of Health, Nigeria, June.

- Federal Ministry of Health (2008) The National Guidelines for TB Infection Control. Abuja: Federal Ministry of Health.

- Federal Ministry of Health (2005) Federal Republic of Nigeria: national antimalarial treatment guidelines. Abuja: Federal Ministry of Health.

- Federal Ministry of Health (2010) Federal Republic of Nigeria: national policy on malaria diagnosis and treatment. Abuja: Federal Ministry of Health, National Malaria and Vector Control Division.

- Kooli C (2021) COVID-19: public health issues and ethical dilemmas. Ethics Med Public Health 17(1-9): 100635.

-

Adeneye AK*, Akinwale OP, Ezeugwu SMC, Olukosi YA, Adewale B, Sulyman MA1, Okwuzu J, Mafe MA, Gyang PV, Soyinka FO, Nwafor T, Henry UE, Musa BD, Adelokiki AO, Bisiriyu AH and Idowu FK. Knowledge and Perception of Buruli Ulcer in Communities of Two Endemic Local Government Areas of Ogun State, Nigeria. Annal of Pub Health & Epidemiol. 2(1): 2022. APHE.MS.ID.000526.

-

Buruli ulcer, Bacille calmette-guérin, Sampling, Snowballing, Leprosy control, Olobutu, World health organisation, Causative organism, Public health, Swabs

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.