Research Article

Research Article

Epidemiology of Visceral Leishmaniasis in Yemen: A Retrospective Study

Sami Ahmed Al Haidari1,2*, Othman S Bahashwan3, Nasreen Bin Azzon3, Rasheed Tawfik Alshami4, Magdi Aldaari3, Abdul Rahman Al-Hadi5 and Hassan A Al-Shamahy6

1NTDs Program, Ministry of Public Health and Population, Yemen

2Department of Community Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Sana’a University, Sana’a, Yemen

3Field Epidemiology Training Program, Ministry of Public Health and Population, Sana’a, Yemen

4Focal point for leishmaniosis control program-Yemen

5Pediatrician, Kuwait University Hospital - Sanaa, Yemen

6Medical Microbiology and Clinical Immunology Department, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Sana’a University

Sami Ahmed Al-Haidari, NTDs Program, Ministry of Public Health and Population, Yemen.

Received Date:October 01, 2024; Published Date:October 09, 2024

Abstract

Background: Visceral Leishmaniasis (VL) is a deadly disease caused by the parasite Leishmania and spread through vectors. It is a neglected tropical disease linked to poverty. Due to the situation in Yemen, there is a lack of recent data on VL. This study aims to provide current information on the prevalence and incidence of VL in each endemic district in Yemen to aid in mapping and implementing effective interventions in these areas.

Methods: A review of data from the National Leishmaniasis Control program in Yemen for the period of January-December 2023 was conducted

for a retrospective descriptive study. All reported cases of VL were diagnosed using the immunochromatographic assay with K39 recombinant

antigen. The study utilized national case definitions and classifications from the WHO. Prevalence and incidence rates were presented for each

district and governorate. Chai square analysis was used to identify associated factors among patients, with a significance level of 0.05.

Results: Out of the 5600 cases suspected of VL reported in 2023 and tested with the rK39 test, 240 (4.4%) were confirmed positive cases

in 71 districts out of a total of 333 districts, all located in 14 out of 22 governorates in Yemen. Among the 240 cases, 152 (63.67%) were males,

with 129 (53.8%) in the age group of 0-59 months and 70 (29.1%) in the age group of 5-14 years. The northern governorates of Yemen showed

significant endemicity, with a country annual incidence rate of 0.7/100,000 and an average annual incidence rate of 2.5/100,000 in the 14 endemic

governorates. The highest incident rates were in Amran, Hajjah, Albayda, and Almahwit governorates (8, 4.7, 3, and 2.7 respectively). Amran, Hajjah,

and Ibb governorates reached epidemic intensity, while Dhamar governorate had high intensity, and other provinces had low intensity or were free

of VL. In terms of districts, the highest incidence rates were in Qaflet Adhar, Al-Shahil, Sawir Bani Qais Altawr, and Hajjah district with rates of 32.58, 23.09, 20.10, and 17.89 respectively. The remaining districts had incidence rates of less than 10. There was a significantly higher rate of VL infection in males compared to females (χ2= 32; p-value < 0.001), with children under 5 years being the most affected age group, accounting for 129 out of 240 cases (53.8%).

Conclusion: Visceral leishmaniasis (VL) continues to primarily affect children in Yemen, particularly males, and is highly prevalent in the

northern governorates. Timely monitoring and response during outbreaks and high mortality rates during treatment are crucial for effective disease

surveillance. Community mobilization and education, along with tailored behavioral interventions, are essential and should be customized to local

needs. Collaboration with stakeholders and other programs targeting vector-borne diseases is vital for successful control of VL in Yemen.

Keywords:Visceral Leishmaniasis; intensity; neglected diseases; Yemen

Abbreviations: IR: Incidence Rate; MoPHP: Ministry of Public Health and Population; NLCP: National Leishmaniasis Control program; RDT: Rapid Diagnostic Test; SPSS: Statistical Package for Social Sciences; VL: Visceral Leishmaniasis; WHO: World Health Organization

Introduction

The Leishmania donovani complex is responsible for the lifethreatening disease of human visceral leishmaniasis (VL) [1], one of the most neglected tropical diseases which has a strong and complex association with poverty [2]. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates 700,000 to 1 million new cases of leishmaniasis annually worldwide, and 26,000–65,000 deaths [3]. Only 25-45% of new cases of visceral leishmaniasis are reported to the WHO each year [4]. There are approximately 350 million people at risk for leishmaniasis, with an annual incidence of about 0.5 million cases of visceral leishmaniasis, which is responsible for 59,000 deaths annually and losses of 2,357,000 disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) [5]. In the Eastern Mediterranean Region (EMRO) of the WHO, L. donovani is a probable cause of anthroponotic VL in Somalia, Sudan, Sudaia Arabian and Yemen.[6] In several countries of the EMR, including Yemen, L. infantum causes zoonotic VL [7].

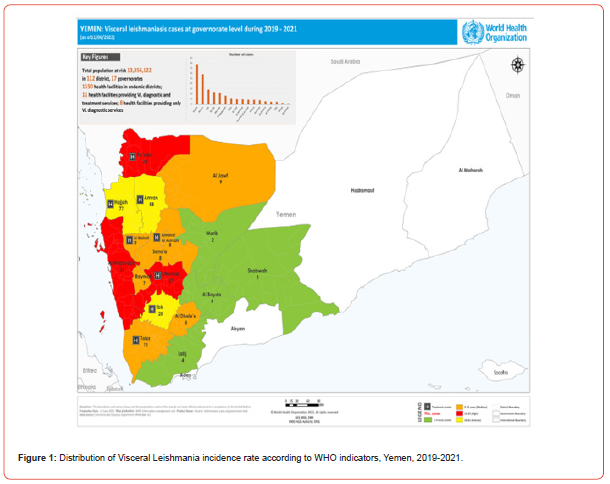

60% of DALYs lost due to tropical diseases in Yemen are caused by leishmaniasis, a major public health problem with nationwide distribution.[8] In Yemen, there have not been continuously published reports from health facilities or districts about endemic areas. There are a variety of methods used to diagnose VL based on aspiration or biopsy samples of tissue (e.g. spleen, liver, bone marrow). [9] L. donovani and a few cases of L. infantum are the most common causes of VL in Yemen according to the governments during the period of 2019-2021. [10] The most severe cases occur in Hajjah, Amran, and Ibb, followed by Sada’ah and Dhamer, then Hodaidah, Jawf, Mahweet, Baidha, Amana, Rayma, and Taiz. The final cases are from Marab, Shabwah, Lahj and Al-Dhalea’a. More than 300 cases were reported each year, with children under 14 years being the most common age group on the map (Figure 1). There are two options in the management of VL in Yemen: Liposomal Amphotericin, Meglumine Antimoniate or Sodium Stibogluconate.

Therefore, the present retrospective study presented updated information on the incidence and trend status of VL at each district for designing effective intervention methods in and around the study areas. (Figure 1)

Methods

Study design setting, and population

This study was conducted at the National Leishmaniasis Control program (NLCP), Yemen, through a retrospective analysis of data from all governorates in Yemen. An area of 527,970 km2 is occupied by Yemen, an arid Middle Eastern country. It shares its borders with Saudi Arabia, Oman, and its 1,900km coastline that runs along the Gulf of Aden and the Red Sea. [11]

Sample size and sampling considerations

Data of all confirmed samples were obtained to determine incidence of VL confirmed by immune chromatographic assay using K39 recombinant antigen (RDT).

Study variables and data collection

The epidemiological surveillance database of NLCP in Yemen was our primary data source. This database is the result of passive surveillance and monitoring based on notifications registered by the epidemiological services of all health sectors in Yemen (health facilities, public hospitals). All data on the official VL-suspected cases case of VL in Yemen during period (January-December 2023) were compiled. This surveillance database contains anonymous patient data including sex, age, residence, time of hospitalization of VL patients and rK39 test. Data regarding positive K39 recombinant antigen cases were obtained in separate excel for analysis.

Laboratory diagnosis

serum samples were collected from all subjects for detection of anti-VL antibodies in human by immunochromatographic assay using K39 recombinant antigen. Immune chromatographic assays using K39 recombinant antigen are easy to perform, they therefore used for early diagnosis of visceral Leishmaniasis at both peripheral and central levels. Specific antibodies are detected against the kinesin related antigen present in L. donovani [12].

According to the manufacturer’s protocol, the rK-39 strip assay was performed. One drop of serum samples was applied to the base of nitro-cellulose ribbons impregnated with rK-39 antigen. The strip was held upright after being dried in the air, and three drops of the test solution (phosphate-buffered saline and bovine serum albumin) were added. A lower red band (control) indicates proper performance of the test, whereas a top red band indicates the presence of anti-rK-39 IgG, indicative of a positive test. The test bands were observed 10 minutes later on the strip.

Data management and statistical analysis

The data was entered into an Excel sheet and transferred to the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS)™ version 23. To allow comparisons between governorates taking the national average, we calculated standardized incidence ratios. The chi-square test was used to determine the association between demographic variables and VL. The significance of p >0.05 was used as statistically significant.

Ethical consideration

Ethical approval of data analysis obtained from MoPHP (NTDs program).

Results

Demographic characteristics of study participants

of the 5600 VL-suspected cases reported during year 2023 who were tested with the rK39 test, 240 (4.4%) were confirmed (positive) cases reported in 71 districts out of a total of 333 districts, all in 14 governorates out of a total of 22 governorates of Yemen. Of all 240 cases, 152 (63.67%) were males, 129 (53.8%) were in agegroup (0-59 months), 70 (29.1%) from age group (5-14 years).

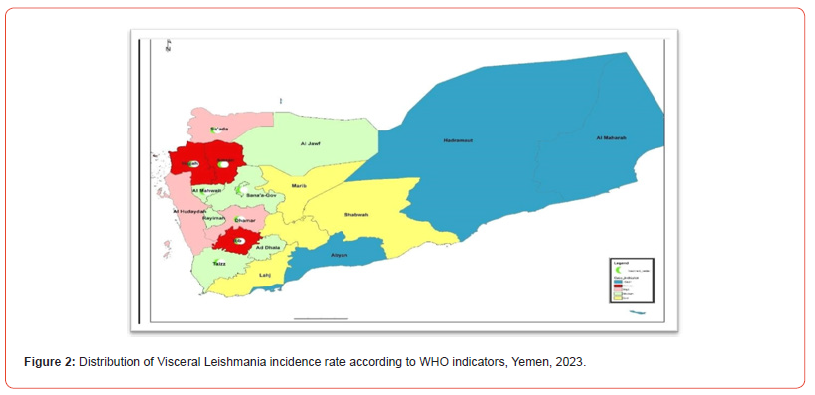

Descriptive statistics

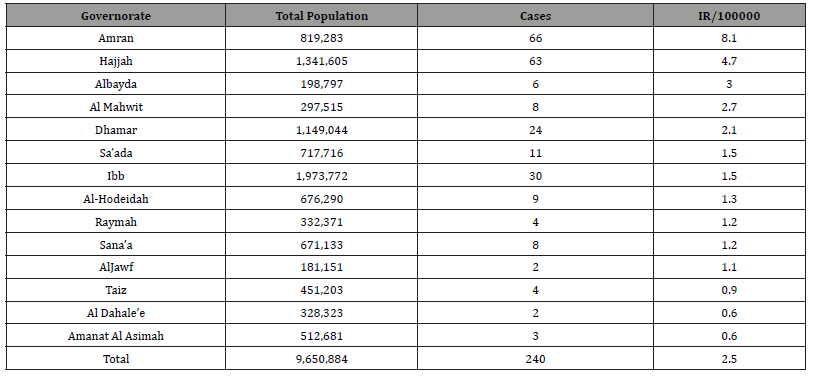

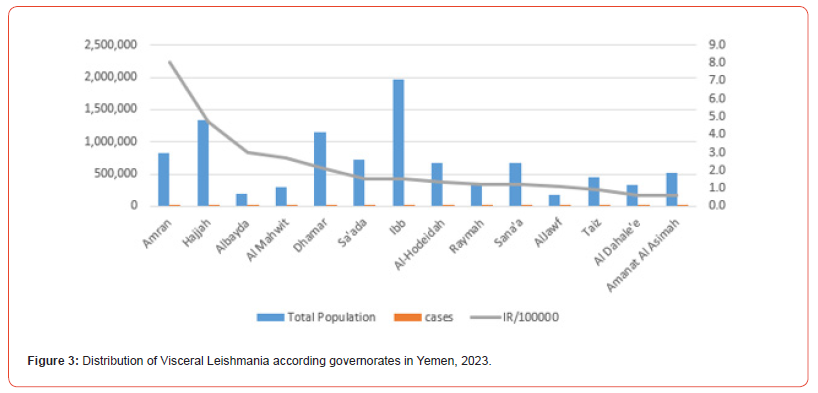

Of the 5600 VL-suspected cases reported during year 2023 who were tested with the rK39 test, 240 (4.4%) were confirmed (positive) cases. According to the national classification (adopted from WHO), the governorates of Amran, Hajjah, and Ibb reached epidemic intense areas, while the governorates of Dhamar were high intense areas, others provinces were low and free on the map below (Figures 2,3). There is significant endemicity in most governorates north of Yemen, the average annual incidence rate was (2.5), at the level of the Republic of Yemen. Thus, incident rates from governorates ware Amran, Hajjah,Albayda and Almahwit governorates (8, 4.7,3 and 2.7 respectively as the (Table 1).(Figure 2)

Table 1:Reported cases and estimated incidence of VL among governorates in Yemen, 2023.

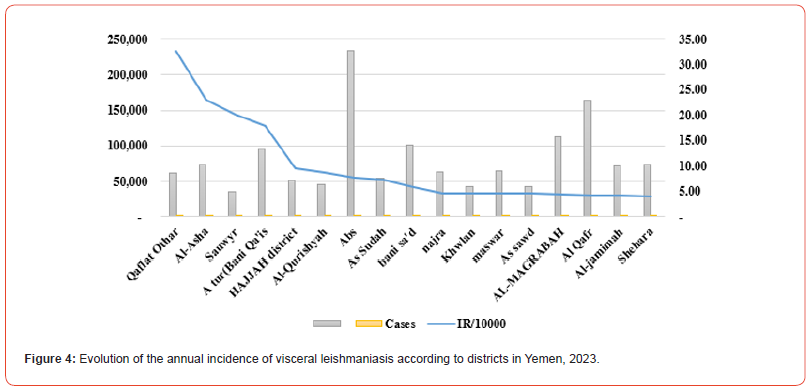

The present study found 240 confirmed cases of VL in 14 governorates out of a total of 22 governorates, with annual incidence rate (IR/100000) in Yemen was (0.7) and the average annual IR in the 14 endemic governorates was (2.5) (Table 1). All the cases were present in 71 districts out of a total of 333 districts, and the IR in the districts of Qaflet Adhar, Al-Shahil, Sawir Bani Qais Altawr and Hajjah district was 32.58 ,23.09 ,20.10 and 17.89 respectively. While the remining districts had an IR of less than 10 as shown in (Figure 3,4).

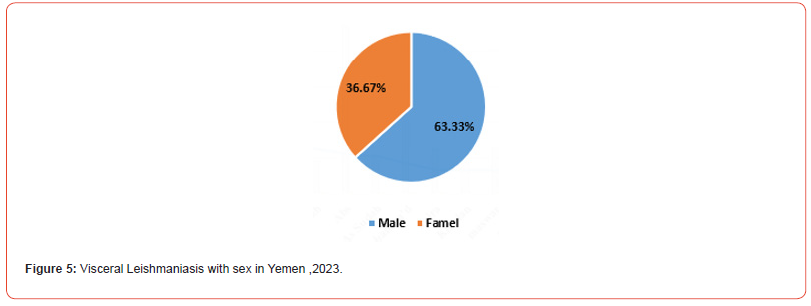

In this study, the majority of 152 (63.67%) of the VL-confirmed (positive) cases were male and there was a significant difference between male and female for VL (χ2= 32; p-value< 0.001) (Figure 5).

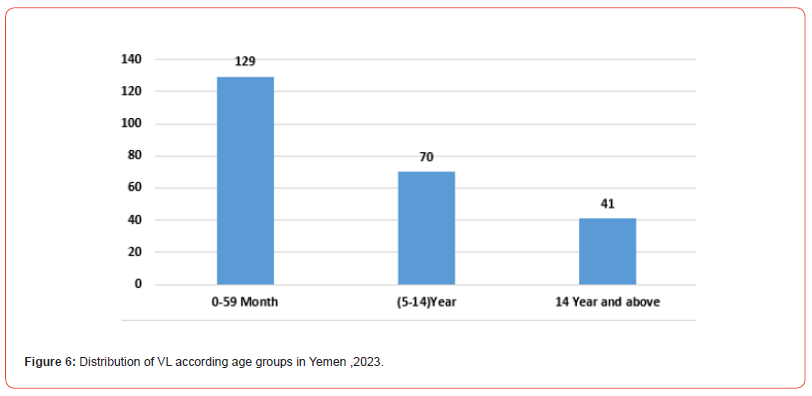

This study revealed that 129/240 (53.8%) of the VL-confirmed cases were in age-groups) 0-59 (months, 70/240 (29.1%) from age group 5-14 and 41/240 (17.1%) from age group 14 years and above (Figure 6).

Discussion

This study analyzed cases of VL in 240 patients diagnosed and treated at the centers of MoPHP (Neglected Tropical Diseases Program in Yemen) in capital city Sana’a and governorates as endemic areas. During year 2023, the reported annual incidence rate of VL in Yemen was 2.5 per 100,000 inhabitants. This annual incidence is comparable to what is observed in EMRO countries endemic for VL. This rate is lower than reported in Sudan and Somalia and higher than remaining countries in EMRO [13]. The prevalence of VL in Yemen was 4.4 %, lower than reported by Abu-Hurub AS study in Yemen in 2022 [9] among adults in the areas endemic with infantile VL in the governorates. Noteworthy, a relatively higher number of VL cases was observed in Amran, Hajjah, and Ibb reached epidemic intensity, while the governorates of Dhamar were high intensity in 2023 (Figure 1), probably because of the political situation during the previous years until now that did not allow the implementation of vector control programs ,shortage in medicine ,shortage in fund , absent training of specialist according local guideline for VL under supervisor of WHO and local expert, and the weak infrastructure in governorates and districts.

One patient from the governorate of Ibb relapse took between four and 12 months. According to analyses, age, time from symptom onset to diagnosis, clinical and laboratory findings on admission (e.g. haemoglobin level, red blood cell count, lymphoma, spleen size) were associated with VL relapse. Both profound anaemia on admission and delays in diagnosis and treatment were strongly associated with delays, which is similar to previous reported studies [14-17]. Unified logistic regression analysis of demographic and clinical variables related to deaths from VL showed that the most significant non-adjusted variables associated with death were weakness, edema, bleeding, other associated infections, jaundice, Leishmania-HIV co-infection, and Leishmania-tuberculosis coinfection, drugs for sex, age range 30-39 years and ≥60 years and being from Alhodaidah, Alamana, Amran and Dhamar, similar to studies reported by [8, 18-20]. The emergence of visceral Leishmania infection in the governorates underlines the need for health and therapeutic achievements for the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of this disease. Furthermore, it is essential to raise the level of consciousness and alertness among healthcare professionals, particularly in vulnerable rural areas.

We found that visceral Leishmania infection is prevalent in rural areas of Yemen, and that the health policy of these areas should more precisely control and treatment of VL cases similar to that of the present study [21, 22]. In Yemen, VL cases are observed throughout the year. All cases were reported between March and July can be explained because of the seasonal transmission of Leishmania infantum from May to October. Similar seasonal trends were reported by other studies [23-25]. The climate exhibits numerous subtropical characteristics, with the average annual temperature ranging from 20 to 30 C and showing little seasonal variation. There is a wide range of relative humidity in the Western Yemen, with high rainfall in the summer and a sub-humid, warmtemperature climate with a distinct dry period in the winter. The annual rainfall ranges from approximately 800–1200 mm, and the majority of this falls from April to October. The middle heights are well watered by perennial streams (Wadies) and small irrigation channels. Small irrigation channels, temporary streams and pools are plentiful during the rainy seasons [23, 24]. The disease was widely spread in Yemen, according to the available information. The incidence rates of VL associated with the transmission of L. infantum by sand flies have been increasing in many foci where living standards have not improved, especially with malnutrition, in the various districts as the (Figure 6).

The sex ratio was statistically significant association between male gender and contracting VL with P.V was 0.01. This is lower than that reported by. [25] and higher than reported by. [9] We would point out that the issue of higher rates of prevalence among males has not yet been completely understood. It has been suggested that there may be a hormonal factor linked to gender or exposure [26]. It is however difficult to comment on this difference, given the small sample size of the latter study and the possibility that it is not representative of the national population. The majority of VL cases were diagnosed in children <5 years of age (53.8%) .VL remains mainly a pediatric disease in Yemen as in other countries such as Algeria, Asia and in Eastern Africa. [25, 27]

Conclusion

In Yemen, VL continues to primarily affect children, with higher rates of occurrence in boys and a high prevalence in the northern governorates. It is crucial to promptly monitor and respond to outbreaks and high mortality rates during treatment for effective disease surveillance. It is also important to educate and mobilize the community with tailored behavioral change interventions. Collaboration with different stakeholders and vector-borne disease control programs is essential for effective control of the disease.

Declarations

The authors declare no conflict.

Consent for publication

The authors received official consent to publish.

Availability of data and materials

Data are available by permission from NLP at the MoPHP.

Competing interests

None.

Funding and disclaimer

The study received no funding.

Authors’ contributions

SA conceived, conducted data collection, run the analysis, and drafted the study; YG supervised and assisted in the analysis and drafting of the study; OB, MGB, AMB facilitated, collaborated, and support the data collection and review the draft.

Acknowledgments

The study wants to Acknowledge the great cooperation of NTDS program staff and those facilitated the conduction of the study.

References

- Kumar A, Pandey SC, Samant M (2020) A spotlight on the diagnostic methods of a fatal disease Visceral Leishmaniasis. 42(10): e12727.

- Thakur L, Singh KK, Shanker V, Negi A, Jain A, etal. (2018) Atypical leishmaniasis: A global perspective with emphasis on the Indian subcontinent. 12(9): e0006659.

- (2022) Organization WH. WHO guideline for the treatment of visceral leishmaniasis in HIV co-infected patients in East Africa and South-East Asia: web annex A: a systematic review on the treatment of visceral leishmaniasis in HIV-Leishmania co-infected persons in East Africa and South-East Asia.

- Farooq I, Singh R, Selvapandiyan A, Ganguly NK (2024) The Burden of Visceral Leishmaniasis: Need of Review, Innovations, and Solutions. Challenges and Solutions Against Visceral Leishmaniasis: Springer pp. 1-17.

- Mahdy MA, Al-Mekhlafi AM, Abdul-Ghani R, Saif-Ali R, Al-Mekhlafi HM, etal. (2016) First molecular characterization of Leishmania species causing visceral leishmaniasis among children in Yemen. 11(3): e0151265.

- Postigo JAR (2010) Leishmaniasis in the world health organization eastern mediterranean region. 36: S62-S65.

- Özbilgin A, Gencoglan G, Tunali V, Çavuş İ, Yıldırım A, etal. (2020) Refugees at the crossroads of continents: a molecular approach for cutaneous leishmaniasis among refugees in Turkey. 65(1): 136-143.

- Wamai RG, Kahn J, McGloin J, Ziaggi GJJoGHS (2020) Visceral leishmaniasis: a global overview. 2(1): e3

- Abu-Hurub AS, Okbah AA, Al-Dweelah HMA, Al-Moyed KA, Al-Kholani AIM, etal. (2022) Prevalence of visceral leishmaniasis among adults in Sana'a City, Yemen. 7(2): 21-26.

- Knight CA, Harris DR, Alshammari SO, Gugssa A, Young T, (2023) Leishmaniasis: Recent epidemiological studies in the Middle East. 13:1052478.

- Noaman A, Binshbrag F, Noaman A, Hadeira M, Al Kebsi A, etal. (2009) Yemen Country Report. ETC Foundation Lesuden. Netherlands; pp.325-40.

- Kühne VEA (2020) Alternative antigens for a point of care test for serodiagnosis of visceral leishmaniasis in East Africa: University of Antwerp.

- Warusavithana S, Atta H, Osman M, Hutin Y (2022) Review of the neglected tropical diseases programme implementation during 2012-2019 in the WHO-Eastern Mediterranean Region.16(9): e0010665.

- Mondal D, Kumar A, Sharma A, Ahmed MM, Hasnain MG, etal. (2019) Relationship between treatment regimens for visceral leishmaniasis and development of post-kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis and visceral leishmaniasis relapse: A cohort study from Bangladesh. 13(8): e0007653.

- Abongomera C, Diro E, Vogt F, Tsoumanis A, Mekonnen Z, etal. (2017) The risk and predictors of visceral leishmaniasis relapse in human immunodeficiency virus-coinfected patients in Ethiopia: a retrospective cohort study. 65(10): 1703-1710.

- Naylor-Leyland G, Collin SM, Gatluak F, den Boer M, Alves F, et al. (2022) The increasing incidence of visceral leishmaniasis relapse in South Sudan: a retrospective analysis of field patient data from 2001-2018. 16(8): e0010696.

- Simão JC, Victória C, Fortaleza CMCB (2020) Predictors of relapse of visceral leishmaniasis in inner São Paulo State, Brazil. 95: 44-9.

- Druzian AF, Souza ASd, Campos DNd, Croda J, Higa MG, etal. (2015) Risk factors for death from visceral leishmaniasis in an urban area of Brazil. 9(8): e0003982.

- Costa CH, Chang KP, Costa DL, Cunha FVM (2023) From infection to death: An overview of the pathogenesis of visceral leishmaniasis. 12(7): 969.

- Maia-Elkhoury ANS, Sierra Romero GA, OB Valadas SY, L Sousa-Gomes M, Lauletta Lindoso JA, etal. (2019) Premature deaths by visceral leishmaniasis in Brazil investigated through a cohort study: A challenging opportunity?. 13(12): e0007841.

- Furtado RR, Alves AC, Lima LV, Vasconcelos dos Santos T, Campos MB, etal. (2022) Visceral Leishmaniasis Urbanization in the Brazilian Amazon Is Supported by Significantly Higher Infection Transmission Rates Than in Rural Area. 10(11): 2188.

- Cruz CdSS, Cardoso DT, Ferreira CL, Barbosa DS, Carneiro M. (2022) Spatial and spatiotemporal patterns of human visceral leishmaniasis in an endemic southeastern area in countryside Brazil. 55: e07022021.

- Asmaa Q, Al-Shamerii S, Al-Tag M, Al-Shamerii A, Li Y, etal. (2017) Parasitological and biochemical studies on cutaneous leishmaniasis in Shara’b District, Taiz, Yemen. 16(1): 47.

- Tabbabi A (2019) Review of leishmaniasis in the Middle East and North Africa. 19(1): 1329-1337.

- Adel A, Boughoufalah A, Saegerman C, De Deken R, Bouchene Z, et al. (2014) Epidemiology of visceral leishmaniasis in Algeria: an update. 9(6): e99207.

- Lockard RD, Wilson ME, Rodríguez NE (2019) Sex-related differences in immune response and symptomatic manifestations to infection with Leishmania species. 2019: 4103819.

- Scarpini S, Dondi A, Totaro C, Biagi C, Melchionda F, etal. (2022) Visceral leishmaniasis: epidemiology, diagnosis, and treatment regimens in different geographical areas with a focus on pediatrics. 10(10): 1887.

-

Sami Ahmed Al Haidari*, Othman S Bahashwan, Nasreen Bin Azzon, Rasheed Tawfik Alshami, Magdi Aldaari, Abdul Rahman Al-Hadi and Hassan A Al-Shamahy. Epidemiology of Visceral Leishmaniasis in Yemen: A Retrospective Study. Annal of Pub Health & Epidemiol. 2(4): 2024. APHE.MS.ID.000545.

-

Visceral Leishmaniasis; intensity; neglected diseases; Yemen

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.