Research Article

Research Article

Evaluating South Australian Marine Parks: is climate change adaptation covered?

Panditharatne CR*

School of Natural and Built Environment, University of South Australia

Panditharatne CR, School of Natural and Built Environment, University of South Australia, Australia.

Received Date: February 21, 2020; Published Date: March 04, 2020

Abstract

One of the key objectives for establishing Marine Parks in South Australia, as identified by the Marine Parks Act of 2007, is to assist in the adaptation to the impacts of climate change in the marine environments. The effectiveness of achieving this objective through the implementation of 19 Marine Park Management Plans will be evaluated in 2022, as required by the above act. To support this evaluation, the 5-year Status Report of Marine Parks South Australia provides comprehensive information on a number of important interventions, including monitoring activities conducted within the parks. The Monitoring, Evaluation and Reporting Plan (MER Plan) too provides guidance on conducting the statutory evaluation of Marine Parks Management Plans. This paper reviews the two documents mentioned above, in order to understand their ability to guide the evaluation process, with respect to implementing climate change adaptation. The review argues that it is necessary to use a more holistic framework that would allow the evaluation of not only drivers, pressures, state and impacts of climate change, but also responses for effective adaptation.

Keywords: Marine parks; Climate change adaptation; Evaluation; Marine park management plans; DPSIR framework

Abbrevations: KEQ: Key Evaluation Questions; DPSIR Framework: Driver-Pressure-State-Impact-Response Framework; MER Plan: Monitoring, Evaluation and Reporting Plan; SEQ: Specific Evaluation Questions

Introduction

Marine parks in South Australia were established under the Marine Parks Act of 2007, which allowed the government to establish 19 marine parks covering over 26,000km2. A key objective of the Marine Park Act (2007) is to assist in the adaptation to the impacts of climate change in the marine environments (see Part 2, Section 8, Clause (1) (b ii) of the Marine Parks Act 2007). In achieving the objectives of the Marine Park Act, different uses for the parks were designated: for instance, zones assigned for General Managed Use allow recreational activities including fishing. Parks assigned for Habitat Protection do not allow prawn trawling, in an effort to conserve the biological and physical value of the terrain. The Sanctuary zone prohibits destructive recreational activities as well as fishing. The final zone, the Restricted Access zone does not allow any activities to take place at the ground level, except research and traditional fishery for persons of Aboriginal origin [1]. The parks were established through a process of public consultations conducted from 2009, bringing in stakeholders such as local anglers and fishermen, local communities, businesses, mine corporations and international business such as the tourism sector. Reliance of local fishermen and recreational fishers on the coastal fishing grounds led to many controversies, especially regarding Sanctuary zones. The belief that restrictions inhibiting access to fishing grounds may diminish their catches was contested by environmental groups, who demanded more strict protection within significant zones [2]. Overall, the marine park intervention is considered an innovative tool for enabling multiple positive outcomes [3]. The Parks and Wilderness Council of South Australia is mandated to provide strategic leadership to the management of the marine park system, and it is important that communities and users of the marine parks are involved in the process [4]. In 2012, Marine Protected Area Management Plans with 15 strategies were authorized by the Government of South Australia. Since the 10-year statutory evaluations of the implementation of these 19 management plans are due in 2022, it is important to ensure that climate change adaptation responses are factored into the evaluation process. As communities determine the success and failure of marine parks according to their own values and interests [5], certain long-term impact such as those caused by climate change might not be easily visible to communities and other stakeholders in the short term. Therefore, it is necessary to ensure that there is an appropriate framework guiding the objective evaluation of the implementation of Management Plans, with respect to climate change adaptation.

Discussion

The 5-Year status report 2012-2017 provides a comprehensive analysis of the Marine Parks and their ongoing trends. While the objective of the status report is not evaluation of the effectiveness of the management plans in delivering the objects of the Marine Parks Act 2007, it attempts a ‘qualitative assessment of whether the management plan strategies are being adequately implemented and the immediate environmental and socio-economic outcomes are being realized’ [6]. Thus, it is clear that the 5-year status report sets out the direction for the statutory evaluation of marine parks. It introduces six Key Evaluation Questions (KEQ), and the KEQ3 is designed in order to understand the extent to which strategies of the Marine Parks Management plans have contributed to enabling marine environments to adapt to impacts of climate change. For this purpose, the specific evaluation questions (SEQs) have been developed. These SEQs identify the monitoring indicators and measures used for information collection; assist in prioritization of monitoring activities; and support evaluation and reporting of information [6]. Climate change impacts on marine ecosystems and adaptation to these impacts are expected to be evaluated through SEQs 16 – 20 stated below.

SEQ 16. What biodiversity and habitats are included within the marine parks network?

SEQ 17. Have sanctuary zones maintained or enhanced biodiversity and habitats?

SEQ 18. Have habitat protection zones maintained biodiversity and habitats?

SEQ 19. Have sanctuary zones maintained or enhanced ecological processes?

SEQ 20. Have sanctuary zones enhanced resilience?

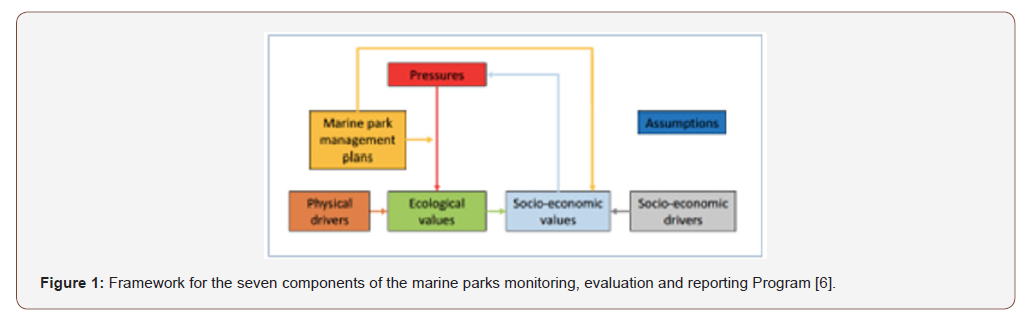

The report proposes to understand the above by measuring parameters such as community level, focal group and focal species level using various indicators, which attempt to ascertain the ecological aspects of the Marine Parks [6]. It is evident from the 5-year status report that numerous high-quality ecological monitoring programs are being undertaken within Marine Parks for this purpose. These monitoring and recording numbers, spatial distribution patterns and temporal changes of marine species are extremely important, but the numbers alone are insufficient when reporting on achieving objective b (ii) of the Marine Park Act – viz, how could Marine Parks assist in the adaptation to the impacts of climate change in the marine environment? The Monitoring, Evaluation and Reporting Framework for Marine Parks (MER Plan) is the key document that provides guidance on reviewing the implementation of Marine Park Management Plans [7]. It requires the evaluation process to examine seven components as indicated in Figure 1 below (Figure 1).

It is clear from Figure 1 that the MER Plan attempts to use a multiplicity of measures and indicators to evaluate the outcomes of the Marine Park Management interventions, as required for a holistic approach. However, attention paid by the MER Plan too, to the KEQ 3, which reflects on climate change adaptation is inadequate. For instance, its Appendix 2 guides addressing KEQ 3 with a single SEQ – ‘Have Sanctuary zones enhanced ecosystem resilience?’, and all indicators and measures designed for this SEQ advocate purely ecological monitoring of parameters such as total number of species, percentage of cover, mean weight, mean length etc. Therefore, it is important that the MER Plan incorporates guidance for assessing whether Management Plans have achieved one of their key objectives in the past ten years – namely, enabling climate change adaptation within marine parks. One of the tools that would allow objective evaluation of climate change impacts and appropriate adaptation measures, is the driver-pressure-stateimpact- response (DPSIR) framework [8]. The DPSIR framework can be used to understand climate change induced driving forces (D) such as ocean acidification and increasing ocean temperatures, which exert pressures on (P) on destructive species like Long Spined Sea Urchin to range-shift into marine parks, causing degradation of the state (S) of the macroalgal seabed’s therein. The impact (I) of such change would be long-term damages to ecologically important species, leading to barren ecosystems [9]. Once the drivers, pressures, changes of state and corresponding impacts are identified, it is necessary to determine the responses (R). Responses for negative climate change impacts could be three types – namely, preventive, adaptive and curative [8]. Each of these responses could target either the driver, pressure, state or even the impact, as deemed effective and efficient by stakeholders. In other words, the MER Plan should not merely advocate the reporting of the impact (for instance, the loss of ecologically important species as measured in numbers) but should also advise on monitoring and reporting about the drivers, pressures, changing states. More importantly, it should provide guidance on monitoring the success or failure of implemented responses. This could be achieved by formulating indicators and measures that would assess different responses implemented. Therefore, following the DPSIR framework in reporting could enable the adaptive management approach sought by the Marine Park Act of 2007, while achieving objective b (ii) of the Marine Park Act, 2007.

Conclusion

South Australia’s marine parks 5-year status report 2012-2017 provides a comprehensive analysis on a multiplicity of operational and management aspects in Marine Park. It is expected that statutory evaluation, which will be conducted in 2020 would provide answers for KEQ 3 – whether the 19 Marine Park Management Plans are effective in addressing climate change impacts. The review of the 5-year status report and the MER Plan indicate a massive effort in monitoring of ecological parameters such as the species abundance but still need more effort in driving a holistic approach in monitoring climate change adaptation responses. It is suggested that following the DPSIR framework can enable such an approach and would also be instrumental in facilitating adaptive management for effective climate change adaptation.

Conclusion

In This Study Different parameters confirmed that microbial contamination and turbidity of water is responsible for much human illness.

Acknowledgement

None.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest.

References

- DEWNR (2014) Zones. National parks and wildlife service, Department of Environment Water and Natural Resources, South Australia.

- Barr LM, Possingham HP (2013) Are outcomes matching policy commitments in Australian marine conservation planning? Marine Policy 42: pp 39-48.

- Swann M (2012) Marine parks: Everyone's a winner [online]. Nature New South Wales 56(3): pp 4-5.

- Department of Environment and Water (DEW) (2015) Activities and Uses in Marine Park Zones. National parks and wildlife service, South Australia.

- Yates KL, Clarke B, Turstan RH (2019) Purpose vs performance: What does marine protected area success look like? Environmental Science & Policy 92: 76-86.

- Bryars S, Page B, Waycott M, Brock D, Wright A (2017) South Australian Marine Parks Monitoring, Evaluation and Reporting Plan. Government of South Australia through Department of Environment Water and Natural Resources Adelaide, South Australia.

- Scholz G, von Baumgarten P, Wilson H, Wright A, Bryars S (2017) Monitoring, Evaluation and Reporting framework for Marine Parks Program DEWNR Technical note 2017/06. Government of South Australia through the Department of Environment Water and Natural Resources Adelaide, South Australia.

- Zhang X, Xue X (2013) Analysis of marine environmental problems in a rapidly urbanizing coastal area using the DPSIR framework: a case study in Xiamen, China. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management 56(5): 720–742.

- Marzloff MP, Melbourne‐Thomas J, Hamon KG, Hoshino E, Jennings S, et al. (2017) Modelling marine community responses to climate‐driven species redistribution to guide monitoring and adaptive ecosystem‐based management. Global Change Biology 23(3): 1360–1360.

- Carr ER, Wingard PM, Yorty SC, Thompson MC, Jensen NK, et al. (2007) Applying DPSIR to sustainable development. International Journal of Sustainable Development & World Ecology 14(6): 543–555.

- DEWNR (2017) South Australia’s marine parks 5-year status. Department of Environment Water and Natural Resources, South Australia.

- Nursey-Bray M, Magnusson A, Bicknell N, Magnusson M, Morison J, et al. (2018) Adapting to change: Prioritising management for the future of the Marine Scalefish Fishery. Marine Policy 95: 153–165.

-

Panditharatne CR. Evaluating South Australian Marine Parks: is climate change adaptation covered?. Ad Oceanogr & Marine Biol. 1(5): 2020. AOMB.MS.ID.000525.

-

Marine parks, Climate change adaptation, Evaluation, Marine park management plans, DPSIR framework, Monitoring evaluation reporting plan, Marine environments, Coastal fishing, Management plans, Community level

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.