Research article

Research article

Total Alkalinity Calculations under International Thermodynamic Equation of Seawater changes

Yaci Gallo Alvarez1*, and Carlos Augusto Ramos e Silva1,2,3

1Programa de Pós-Graduação Dinâmica dos Oceanos e da Terra - Instituto de Geociências - Universidade Federal Fluminense - Av. Gen. Milton Tavares de Souza s/n – Gragoatá, Campus da Praia Vermelha, Brazil.

2Departamento de Biologia Marinha - Instituto de Biologia - Universidade Federal Fluminense - Bloco M - Rua Prof. Marcos Waldemar de Freitas Reis s/n - São Domingos, Brazil..

3Núcleo de Estudos em Biomassa e Gerenciamento de Água – NAB - Rua Edmundo March s/n - Campus da Praia Vermelha, Brazil

Yaci Gallo Alvarez, Programa de Pós-Graduação Dinâmica dos Oceanos e da Terra - Instituto de Geociências - Universidade Federal Fluminense - Av. Gen. Milton Tavares de Souza s/n – Gragoatá, Campus da Praia Vermelha, Brazil

Received Date:June 05, 2025; Published Date:June 11, 2025

Abstract

Since several physical processes in the oceans are driven by seawater properties, such as salinity and temperature, the thermodynamic approach provided by the new Thermodynamic Equation of Seawater (TEOS-10) is expected to lead to a better and more realistic representation of the ocean, when compared to the previous equation (EOS-80). Here we investigate how two distinct representations of salinity can affect the carbonate system investigation, in particular Total Alkalinity. In May 2014, 34 CTD casts were performed at four transects through the platform and continental slope of the Sergipe–Alagoas sedimentary basin. Bottle samples were collected in vertical profiles measuring from surface to 2000 meters depth to provide a comprehensive view of the main water masses distribution. Total alkalinity (μmol kg-1) was obtained mathematically in AQM program and the results revealed that the adoption of Absolute Salinity (g kg-1) provided a difference of 0.33% when compared to Practical Salinity (psu). The choice of the methodology leads to an associated error in calcite and aragonite saturation state findings, commonly used to track ocean acidification.

Keywords: Atlantic ocean; total alkalinity; salinity; sea water; water mass

Introduction

The western tropical South Atlantic Ocean is a crossroad of an important meridional transfer of water masses and an ideal place to observe and monitor properties transport changes in the upper and lower branches of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation - AMOC [1–5]. The transport of physical and chemical properties by ocean currents is strongly influenced by the global hydrological cycle and may accompany the oceanic freshwater transport, such as dissolved inorganic carbon and total alkalinity [6,7].

Total alkalinity (TA) is one of the four fundamental parameters to characterize the marine carbonate system [8] and, in natural waters, can be defined as the number of moles of protons equivalent to the excess of proton acceptors over proton donors in one kilogram of solution [9]. When expressed in moles or charge equivalents per kilogram of solution, TA is not affected by variations in temperature or pressure. As a result, TA is a carbonate system parameter that mixes conservatively and is linearly correlated with salinity in marine waters [8,10-13].

Due to its stable and conservative nature, TA can be combined with total dissolved inorganic carbon, pH, or the partial pressure of CO2 (pCO2) to estimate unmeasured carbonate system parameters and characterize complex biogeochemical processes [8]. Thus, identify the mechanisms that modify the TA of seawater is becoming increasingly important to understand the effects of ocean acidification resulting from the addition of anthropogenic CO2 to surface water [12,14,15]. However, the choice of the methodology to investigate this parameter can lead to significant changes in the interpretation of the results obtained and in the monitoring of ocean acidification. In this work, we performed a statistical comparison to evidence (a) TA variability applying EOS-80 and TEOS-10 equations of state and (b) how different interpretations of TA values can then propagate through carbonate system calculations, consequently distorting biogeochemical interpretations of calculated parameters.

Materials and Methods

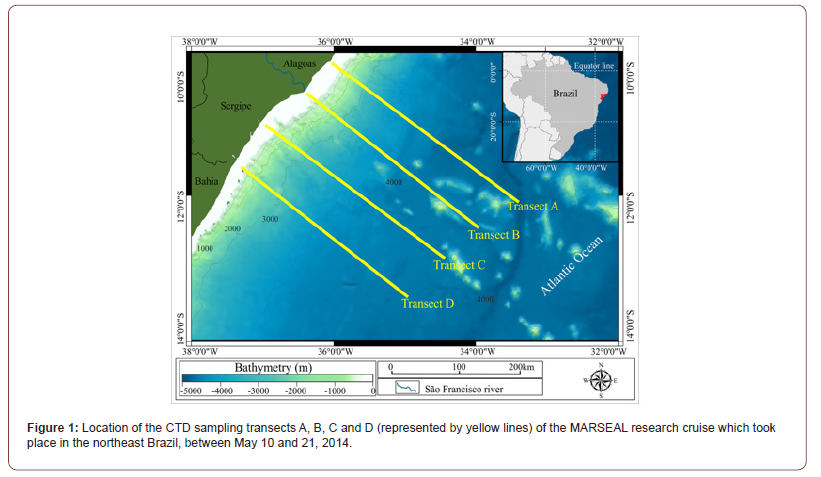

The hydrographic survey was carried out in four perpendicular transects in the northeast coast of Brazil between May 10 and 21, 2014 in the beginning of the rainy season (127 mm3/month) (INMET CDP, 2014). The sampling effort took place onboard the R/V Seward Johnson during a cruise through the Sergipe- Alagoas Basin (SEAL basin), which was made possible by financial resources and logistical support provided by the MARSEAL Project (PETROBRAS/CENPES). The transects were carried out along the cruise track, from 10.165°S 36.024°W near the coast to 13.394°S at 34.954°W offshore (Figure 1). The survey included 34 Conductivity–Temperature–Depth (CTD) casts with 143 sampling depths, from 5 to 1650 m. The CTD work was carried out with a SBE9 plus coupled in a General Oceanics rosette with capacity for 24 oceanographic Niskin and Go-Flo type bottles. Water samples were collected at different depths to provide physicochemical parameters of the water masses present in each profile and the calibration of conductivity.

The total pH of the water samples analyzed was

where Eo is the standard electrode potential, which was determined by titrating a 0.7 m NaCl solution with 0.179 M HCl [16]. The pHT (total scale) values were measured immediately after each collection at a constant temperature of 25°C in a thermostatic cell connected to a microprocessed thermostatic bath with external circulation (Qimis) to avoid temperature bias [17]. The determinations were made by the Thermo Scientific Orion Star potentiometer coupled to the Orion glass reference electrode with a 0.7 m NaCl outer chamber filling solution, model 8102BNUWP. The analytical slope for the electrode was within ± 0.13 mV (teoretical Nersnt value at 25°C). The electrode was calibrated with a “Tris” buffer (0.04 m) prepared in the laboratory [18], where pH values were assigned by spectrophotometry (m-cresol method) [18- 21]. The “Tris” buffer allows accuracy of 0.001 pH units [18,22]. Subsequently, using the AQM program, the pH results were corrected for the temperature recorded at the sampling moment

For the determination of TA(a), water samples were filtered in a Nalgene filtration system through GF/F filters before being transferred to BOD type flasks (300 mL, from the Kimble brand) and immediately analyzed [20]. The potentiometric determination was conducted with duplicate samples in an open thermostated glass cell, where 3 mL (to obtain v1) and 10 mL (to obtain v2) of HCl 0.1 M were added to each 100 mL sample. The method consists in determining the slope of the line by obtaining two points for the function of Gran (F): F (1) defined by v1 and F (2) defined by v2 [24]. A Thermo Scientific Orion Star potentiometer coupled to the Orion glass reference electrode cell, model 8102BNUWP was used for potentiometric determinations. The pH electrode was calibrated daily with “Tris” buffer (0.04 m) for sample readings (maximum 15 samples per day). The electrode’s percent efficiency ranged between 99.49% and 99.54% concerning the theoretical Nernst value (59 mV). The analytical precision and accuracy can be seen in [12], as well as the results of the other parameters of carbonate system.

Gibbs Seawater (GSW) Oceanographic Toolbox [25] were used to calculate the hydrographic parameters according to the Thermodynamic Equation of Seawater 2010 (TEOS-10): Absolute Salinity (g kg-1) (SA) from Practical Salinity (PSU) (SP), and Conservative Temperature (°C) (Θ) of seawater from insitu temperature (°C). The new standard is thermodynamically consistent, valid over a wider range of temperature and salinity, and includes a mechanism to account for composition variations in seawater [26].

TA was calculated with the AQM program [12,21,27,28] for SP (EOS-80) and SA (TEOS-10) through the equation proposed by [29] for waters of the Atlantic and Pacific oceans by the GEOSECS Program: TA(μmol) = 660+47.6 S, where S represents salinity. A variation in the salinity values, which is the basis of the TA calculation in AQM program, is expected to lead changes in TA values found. The carbonate saturation of calcite and aragonite (ΩCalc and ΩArag ) were calculated using the carbonate system dissociation constant K as described in [12].

Temperature, salinity and pressure data were used to compose the mean hydrographic section at 11°S and to derive the neutral density surfaces (γn) [30]. Neutral densities are the continuous analogue of discretely defined and locally referenced potential density surfaces and have a better accuracy in finding the best practice isopycnal surface in the global ocean [30]. The Neutral Density code is available as a package of MATLAB and/or FORTRAN routines which enable the user to fit neutral density surfaces to arbitrary hydrographic data. The selection of γn to distinguish the water masses boundaries follows the values proposed by [1] and applied by [3] for this latitude: γn = 24.5kg m−3 to distinguish surface waters from South Atlantic Central Water (SACW), γn = 26.8kg m−3 for the lower limit of waters supplying the Equatorial Undercurrent, γn = 27.7kg m−3 for the boundary between Antarctic Intermediate Water (AAIW) and the North Atlantic Deep Water (NADW). NADW layer were subdivided into upper, middle, and lower NADW using γn = 28.025kg m−3 and γn = 28.085kg m−3 .

Data normality was verified using the Shapiro-Wilks test, and based on this result, the non-parametric Kruskal Wallis test was chosen for comparisons between groups. All statistical tests were performed using the Statistica 7.0 software (TIBCO) with a significance level set at p<0.05.

Results

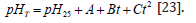

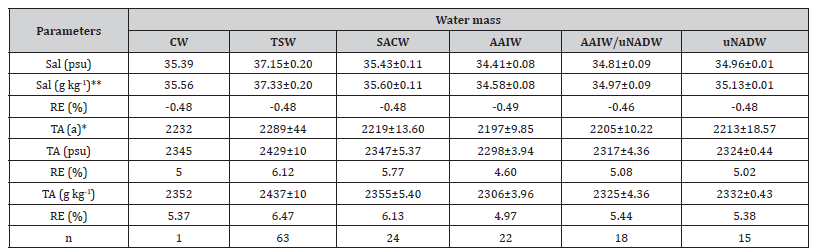

The Absolute Salinity - Conservative Temperature Diagram (SA – Θ Diagram) shows the five water masses identified up to 2000 m depth at 11°S section: Coastal Water (CW), Tropical Surface Water (TSW), SACW, AAIW and uNADW (Figure 2). Applying neutral density surfaces in the analysis of oceanographic data, we identified 1 sample in CW, 63 samples in TSW, 24 samples in SACW, 22 samples in AAIW, 18 samples in the boundary between AAIW and upper NADW (uNADW) and 15 samples in uNADW. At the surface, TA concentrations are high with mean values of 2436 μmol kg-1 (SA 37.33 g kg−1 −Θ 27.71°C) under TEOS- 10 and 2428 μmol kg-1 (SP 37.15 − θ 27.80°C) under EOS- 80, reflecting the signature of the warm and high-salinity TSW. The exception is CW, characterized by high temperatures and lower salinities values due to river inflow and mixing with TSW (SA 35.56 g kg−1 − 27.89°Cand SP 35.39 − θ 27.91°C) . This water mass presented TA 2352 μmol kg-1 (TEOS-10) and 2344 μmol kg-1 (EOS-80).

Along the pycnocline, SACW is recognized by its linear SA – Θ relationships, although the samples were centered around 250m depth. The mean TA concentrations observed were 2354 μmol kg-1 under TEOS-10 (SA 35.60 g kg−1 − Θ 14.44°C) and 2346 μmol kg-1 under EOS-80 (SP 35.43 – θ 14.47°C) . In the intermediate layer (500–1200 m), AAIW can be identified by the salinity minimum in the South Atlantic Ocean (SA 34.58 g kg−1 − Θ 4.67°Cand SP 34.41 − θ 4.67°C) and lower mean TA values (TEOS-10 = 2305 μmol kg-1 and EOS-80 = 2297 μmol kg-1). At the transition layer between AAIW and uNADW, a saltier water mass, we observe an increase of salinity (SA 34.97 g kg−1 – Θ 4.20°C, SP 34.81 − θ 4.21°C) and TA (TEOS- 10 = 2324 μmol kg-1 and EOS-80 = 2316 μmol kg-1). Below 1500 m, lays the uNADW with TA 2332 μmol kg-1 under TEOS-10 (SA 35.13 g kg−1 − Θ 3.88°C) and 2324 μmol kg-1 under EOS-80 (SP 34.96 − θ 3.89°C).

The difference between TEOS-10 and EOS-80 for TA calculations is expected since Practical Salinity (SP) is numerically smaller than the mass fraction of dissolved matter when this mass fraction is expressed as grams of solute per kilogram of seawater, represented by SA (TEOS-10). The percentage Relative Error (RE%) in salinity is 0.47% in CW, TSW and SACW, and 0.48% in AAIW, in the transition layer between AAIW and NADW, and uNADW. The absolute errors are 0.17 and 0.18, respectively. Consequently, this variation in the salinity values, which is the basis of the TA calculation in AQM, is expected to change TA calculated values. Therefore, on average, TA TEOS-10 is 0.34% higher than TA EOS-80 across all water masses. In CW we observed an absolute error of 7.95 μmol kg-1 between TA TEOS-10 and TA EOS-80, while TSW presented the highest absolute error of 8.35 μmol kg-1, followed by SACW with 7.99 μmol kg-1, AAIW with 7.89 μmol kg-1, the transition layer between AAIW and uNADW presented 7.97 μmol kg-1 and uNADW 7.96 μmol kg-1.

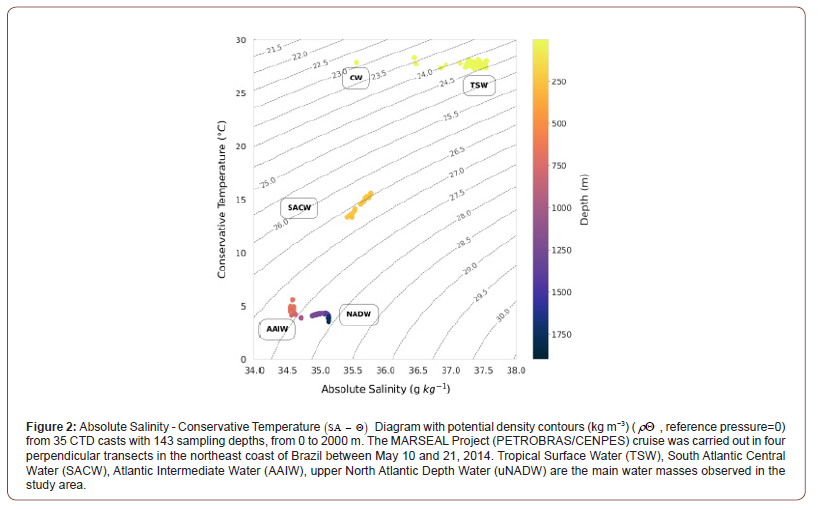

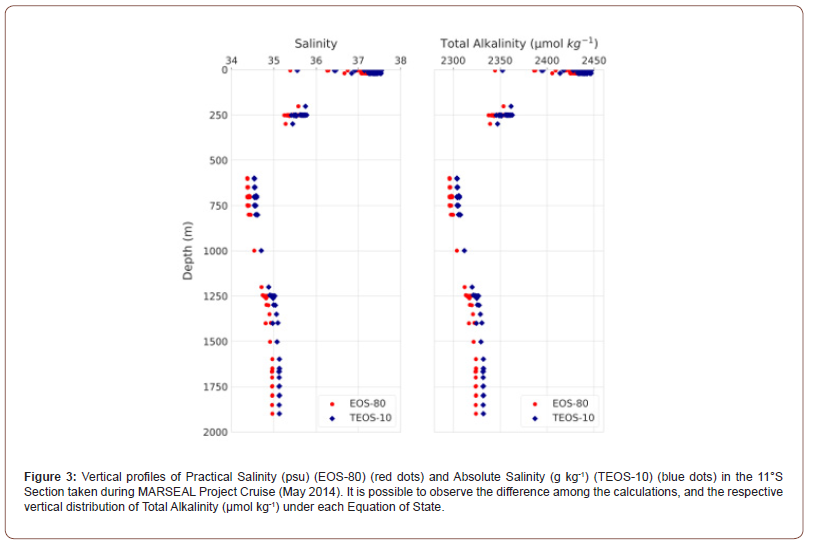

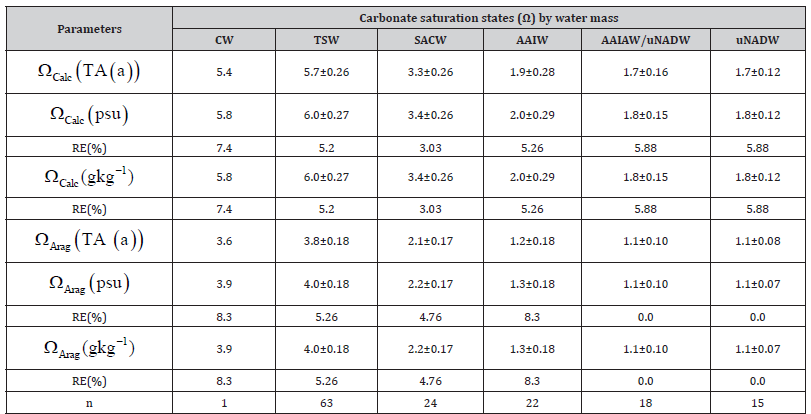

The distribution of TA EOS-80 and TA TEOS-10 throughout the water column correlates strongly with SP and SA distributions, respectively, and follow the water masses distribution pattern. The linear correlation between TA EOS-80 and SP and and TA TEOS-10 and SA is both: T_ALK=47.6S+660 μmol kg-1 (n = 143, R2 = 0.99987 (Figure 3). Furthermore, the calculation of calcite and aragonite saturation states (Ω) for EOS-80 and TEOS-10 reveals that the water masses at 11°S section are supersaturated (Ω >1) with respect to both minerals throughout the water column and vary within water masses (Figure 4). The mean values of the calcite saturation state (ΩCalc) range between 1.7 to 5.7, with the highest values observed in TSW ( 5.7) ΩCalc= and SACW ( 3.3) ΩCalc = . The lowest mean values (1.7>ΩCalc>1.9) were recorded for AAIW, AAIW/uNADW and uNADW. The saturation state obtained by the EOS-80 and TEOS-10 did not differ significantly (Relative Error (RE) = 0.73% to 0.86%) although the saturation obtained by EOS- 80 and TEOS-10 for all water bodies varied between 0.3 and 1.3. The opposite scenario was found for aragonite saturation state (Ωarag) , with the highest mean values observed in TSW ( 3.8) Ωarag = and SACW ( 2.1) arag Ω = and the lowest values recorded for AAIW, AAIW/uNADW and uNADW (1.1> Ωarag>1.2) ontrasting with calcite saturation, the relative error was quite significant (above 1%) in the average obtained by the EOS-80 and TEOS-10, in the SACW it reached 15.6% and in the AAIW 5.4%.

Discussion

Salinity variations are primarily driven at the surface and at coastal boundaries by processes as evaporation, precipitation, brine rejection, ice melt and river runoff and satisfies an advectiondiffusion equation away from these boundaries [31]. The SP has long been used to determine the salinity of seawater and other physical properties, but while this provides a good representation of the salinity, it has been recognized that there are limitations at the conductivity method [32-42]. The variations in composition, due to the addition of nutrients or inorganic carbon [32,43] can lead to implications for neutral density surfaces and ocean circulation. Studies to address the limitations of the EOS-80 [44] have demonstrated that variations in seawater composition can increase the salinity of seawater by up to 0.026 g kg-1 and the density by 0.020 kg m-3. The new equation of state (TEOS-10) accounts for variations in the composition of seawater through the introduction of SA, which includes the sum of all dissolved components in seawater [45]. At the 11°S section, the percentage variance between SP and SA is 0.4%. Consequently, according to the analyzed equations, TA is 0.33% to 0.34% higher under TEOS-10 when calculated from SA. However, it maintains the same percentage distribution as TA calculated from SP. According to [11] TA varies from 2.180 to 2.450 μmol kg-1 in the Atlantic Ocean and the data presented in this work are within these values. The distribution of TA is similar to the salinity distributions that follow the water masses throughout the water column [46].

The next largest uncertainty in our ability to predict the properties of seawater arises from spatial and temporal variations in the composition of seawater. These give rise to salinity variations of up to 0.03 g kg−1 in the open ocean and may exceed 0.1 g kg−1 in coastal waters or estuaries due to different biogeochemical processes that may affect the results. Use of these corrections does not appear to significantly degrade the prediction of thermodynamic properties and in some cases improves them [31]. Recently, [12] compared total alkalinity concentrations obtained through analytical methods with those estimated by empirical models across the five water masses defined in the same study area. The empirical models used to calculate total alkalinity did not account for the effects of the different salinity parameters discussed here, nor their influence on carbonate saturation values.

We observed a relative error of 4.5% to 6.5% between the analyzed and calculated TA (Table 1). The RE (%) is 0.3% higher under TEOS-10 than under EOS-80. The relationship between TA and salinity is well established, and several researchers have proposed empirical equations [11,29,47]. The differences between the predicted values (Absolute Salinity, g kg-1) and the measured values (Practical Salinity, psu) are somewhat larger than those reported by [48], which may be due to the applied equation and the relatively small sample size analyzed here for each water mass (n < 65), as previously noted by [12]. The relative errors of the salinity parameters are low (<0.5%) and do not appear to significantly affect the TA values (psu or g kg-1); rather, TA seems to be influenced more by the equation applied (Table 1). On the other hand, the values of the saturation state of calcite and aragonite obtained by the AQM program using TA (psu) and TA (g kg-1) showed no significant discrepancy compared to the reference values Ω_ Calc (TA(a)) andΩ_ Arag (TA(a)). The difference in Ω values calculated from TA (psu) and TA (g kg-1) was negligible (0.0). However, carbonate saturation varied significantly among the different water masses (p < 0.05), as expected. The differences between the analyzed and calculated saturation states of calcite and aragonite were greater at the surface than in the deeper water masses (Table 2).

Table 1:Variations in TA (μmol kg-1) were obtained analytically (TA (a)) and calculated under EOS-80 with Practical Salinity (TA (psu)) and TEOS-10 with Absolute Salinity (TA (g kg-1)) utilizing the AQM program (Ramos e Silva et al., 2010, Ramos e Silva et al., 2017a, Ramos e Silva et al., 2017b, Ramos e Silva et al., 2017c, Ramos e Silva et al., 2022). The results are summarized by the main water masses found: Coastal Water (CW), Tropical Surface Water (TSW), South Atlantic Central Water (SACW), Antarctic Intermediate Water (AAIW), Antarctic Intermediate Water - North Atlantic Deep Water (AAIW/uNADW), upper North Atlantic Deep Water (uNADW). The percent Relative Error (RE%) for each calculation is also presented, where TA (a)* was used as the reference value for TA and Absolute Salinity ** was used as a reference value for salinity. And n is the sample size.

Table 2:Effects of the practical salinity (psu) and absolute salinity (g kg-1) on the carbonate saturation states with respect to calcite (Ωcalc) and to aragonite (Ωarag) . The values were obtained by total alkalinity calculated under EOS-80 (TA (psu)) and TEOS-10 (TA (g kg-1)) with the AQM program (Ramos e Silva et al., 2017a, Ramos e Silva et al., 2010, Ramos e Silva et al., 1017b, Ramos e Silva et al., 1017c). The pH (total scale, k) and temperature values used were according to (Ramos e Silva et al., 2022). The values are presented by the main water masses found in the region: Coastal Water (CW), Tropical Surface Water (TSW), South Atlantic Central Water (SACW), Antarctic Intermediate Water (AAIW), Antarctic Intermediate Water - North Atlantic Deep Water (AAIW/uNADW), upper North Atlantic Deep Water (uNADW). The percent Relative Error (RE%) for each calculation is also presented, where the parameters obtained analytically (TA(a)) are the expected values. And n represents the sample size.

A question that deserves to be raised is whether a difference of less than 8.3% between the analyzed and calculated values of carbonate saturation state should be considered significant. In the context of a carbonate system monitoring program for water masses in the western tropical Atlantic—an important observational corridor for the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC), where data are still scarce—the correct answer may well be yes. Increasing oceanographic research efforts in this region would be essential for expanding available data, deepening scientific understanding, and improving empirical models for the Atlantic Ocean.

Conclusion

The methodology selected for calculating carbonate system variables must be chosen carefully, as variations cannot be neglected when accounting for spatial and temporal variability. Long-term time series analyses, combined with high-precision data, are essential to advance our understanding of the ocean carbon cycle and marine biogeochemistry. Empirical models may eventually replace laboratory determinations of total alkalinity (TA), calcium, and boron, since the carbonate system tends to exhibit only slight differences between calculated and measured values. This would streamline the entire process and reduce operational costs.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by grants from the MARSEAL Project (PETROBRAS/CENPES) and Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Schott FA, Dengler M, Zantopp R, Stramma L, Fischer J, et al. (2005) The Shallow and Deep Western Boundary Circulation of the South Atlantic at 5°–11°S. Journal of Physical Oceanography 35(11): 2031-2053.

- Zhang D, Msadek R, Mcphaden MJ, Delworth T (2011) Multidecadal variability of the North Brazil Current and its connection to the Atlantic meridional overturning circulation. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans 116(C4): C04012.

- Hummels R, Brandt P, Dengler M, Fischer J, Araujo M, et al. (2015) Interannual to decadal changes in the western boundary circulation in the Atlantic at 11°S. Geophysical Research Letters 42(18): 7615-7622.

- Rühs S, Getzlaff K, Durgadoo JV, Biastoch A, Böning CW (2015) On the suitability of North Brazil Current transport estimates for monitoring basin-scale AMOC changes. Geophysical Research Letters 42(19): 8072-8080.

- Herrford J, Brandt P, Kanzow T, Hummels R, Araujo M, et al. (2021) Seasonal variability of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation at 11°S inferred from bottom pressure measurements. Ocean Science 17(1): 265-284.

- Stoll Mhc, Aken HM, Barr HJW, Boer CJ (1996) Meridional carbon dioxide transport in the northern North Atlantic. Marine Chemistry 55(3-4): 205-216.

- Robbins Paul E (2001) Oceanic carbon transport carried by freshwater divergence: Are salinity normalizations useful? Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans 106(C12): 30939-30946.

- Sharp JD, Byrne RH (2020) Interpreting measurements of total alkalinity in marine and estuarine waters in the presence of proton-binding organic matter. Deep Sea Research Part I: Oceanographic Research Papers 165(17): 103338.

- Dickson AG (1981) An exact definition of total alkalinity and a procedure for the estimation of alkalinity and total inorganic carbon from titration data. Deep Sea Research Part A. Oceanographic Research Papers 28(6): 609-623.

- Broecker WS, Peng TH (1982) Tracers in the Sea. Lamont-Doherty Geological Observatory, Columbia University, Palisades, NY.

- Millero FJ, Lee K, Roche M (1998) Distribution of alkalinity in the surface waters of the major oceans. Marine Chemistry, 60(1-2): 111-130.

- Ramos E Silva CA, Monteiro NSC, Cavalcante LC, Junior WT, Carneiro MER, et al. (2022) Inventory of water masses and carbonate system from Brazilian’s northeast coast: monitoring ocean acidification. PLoS One 17(7): e0271875.

- Ramos E Silva CA, Rocha AA, Ribeiro CH, Villac MC, Silva MP, et al. (2023) The role of Cabo Frio upwelling in the control of marine carbonate chemistry and ecosystem functioning. Scientific Reports 13: 11438.

- Feely RA, Sabine CL, Lee K, Berelson W, Kleypas J, et al. (2004) Impact of Anthropogenic CO2 on the CaCO3 System in the Oceans. Science 305(5682): 362-366.

- Ramos E Silva CA (2022) Who is responsible for climate change: Celestial phenomena or human activity? International Journal of Environment and Climate Change 12(11): 3462-3470.

- Ramos E Silva CA, Liu X, Millero FJ (2002) Solubility of siderite (FeCO3) in NaCl solutions. Journal of Solution Chemistry 31: 97-108.

- Perez FF, Fraga F (1987) The pH measurements in seawater on the NBS scale. Marine Chemistry 21(4): 315-327.

- Millero FJ, Zhang JZ, Fiol S, Sotolongo S, Roy RN, et al. (1993) The use of buffers to measure the pH of seawater. Marine Chemistry 44(2-4): 143-152.

- Clayton TD, Byrne RH (1993) Spectrophotometric seawater pH measurements: total hydrogen ion concentration scale calibration of m-cresol purple and at-sea results. Deep Sea Research Part I: Oceanographic Research Papers 40(10): 2115-2129.

- Dickson AG, Goyet C (1994) DOE. Handbook of methods for the analysis of the various parameters of the carbon dioxide system in sea water. Version 2. ORNL/CDIAC-74. National Lab, TN, USA.

- Ramos E Silva CA, Sternberg LSL, Davalos PB, Souza FES (2017b) The impact of organic and intensive farming on the tropical estuary. Ocean & Coastal Management 141: 55-64.

- Millero FJ (1986) The pH of estuarine waters. Limnology and Oceanography 31(4): 839-847.

- Millero FJ (1995) Thermodynamics of the carbon dioxide system in the oceans. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 59(4): 661-677.

- Van Den Berg CMG, Rogers H (1987) Determination of alkalinities of estuarine waters by a two-point potentiometric titration. Marine Chemistry 20(3): 219-226.

- Mcdougall TJ, Barker PM (2011) Getting started with TEOS-10 and the Gibbs Seawater (GSW) Oceanographic Toolbox. PP. 28.

- Pawlowicz R, Mcdougall T, Feistel R, Tailleux R (2012) An historical perspective on the development of the Thermodynamic Equation of Seawater – 2010. Ocean Science 8(2): 161-174.

- Ramos E Silva CA, Miranda LB, Dávalos PB, Silva MP (2010) Hydrochemistry in tropical hyper-saline and positive estuaries. Pan-American Journal of Aquatic Sciences 5(3): 432-443.

- Ramos E Silva CA, Davalos PB, Silva MP, Miranda LB, Calado L (2017a) Variability and Transport of Inorganic Carbon Dioxide in a Tropical Estuary. Journal of Oceanography and Marine Research 5(1): 1000155.

- Hunter KA (1998) The temperature dependence of pH in surface seawater. Deep-Sea Research Part I 45(11): 1919-1930.

- Jackett DR, Mcdougall TJ (1997) A Neutral Density Variable for the World’s Oceans. Journal of Physical Oceanography 27(2): 237-263.

- Wright DG, Pawlowicz R, Mcdougall TJ, Feistel R, Marion GM (2011) Absolute Salinity, “Density Salinity” and the Reference-Composition Salinity Scale: present and future use in the seawater standard TEOS-10. Ocean Science 7(1): 1-26.

- Brewer PG, Bradshaw A (1975) The effect of non-ideal composition of seawater on salinity and density. Journal of Marine Research 33: 157-175.

- Millero FJ (2000) Effect of changes in the composition of seawater on the density-salinity relationship. Deep Sea Research Part I: Oceanographic Research Papers 47(8): 1583-1590.

- Millero FJ, Kremling K (1976) The densities of Baltic Sea waters. Deep Sea Research and Oceanographic Abstracts 23(12): 1129-1138.

- Millero FJ, Gonzalez A, Ward GK (1976a) The density of seawater solutions at one atmosphere as a function of temperature and salinity. Journal of Marine Research 34: 61-93.

- Millero FJ, Gonzalez A, Brewer PG, Bradshaw A (1976b) The density of North Atlantic and North Pacific deep waters. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 32(2): 468-472.

- Millero FJ, Lawson D, Gonzalez A (1976c) The density of artificial river and estuarine waters. Journal of Geophysical Research 81(6): 1177-1179.

- Millero FJ, Chetirkin PV, Culkin F (1976d) The relative conductivity and density of standard seawaters. Deep-Sea Research 24: 315-321.

- Millero FJ, Forsht, D, Means, D, Gieskes J, Kenyon K (1978a) The density of North Pacific Ocean waters. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans 83(C5): 2359-2364.

- Millero FJ, Means D, Miller CM (1978b) The densities of Mediterranean Sea waters. Deep-Sea Research 25(6): 563-569.

- Poisson A, Lebel J, Brunet C (1980) Influence of local variations in the ionic ratios on the density of seawater in the St. Lawrence area. Deep Sea Research Part A. Oceanographic Research Papers 27(10): 763-781.

- Poisson A, Lebel J, Brunet C (1981) The densities of western Indian Ocean, Red Sea and eastern Mediterranean surface waters. Deep Sea Research Part A. Oceanographic Research Papers 28(10): 1161-1172.

- Connors DN, Weyl PK (1968) The partial equivalent conductance of salt in seawater and the density-conductance relationship. Limnology and Oceanography 13(1): 39-50.

- Millero FJ, Poisson A (1981) International one-atmosphere equation of state of seawater. Deep Sea Research Part A. Oceanographic Research Papers 28(6): 625-629.

- Millero FJ, Feistel R, Wright DG, Mcdougall TJ (2008) The composition of standard seawater and the definition of the reference-composition salinity scale. Deep Sea Research Part I: Oceanographic Research Papers 55(1): 50-72.

- Millero FJ (2007) The marine Inorganic Carbon Cycle. Chemical Reviews 107(2): 308-341.

- Egleston ES, Sabine CL, Morel FMM (2010) Revelle revisited: Buffer factors that quantify the response of ocean chemistry to changes in DIC and alkalinity. Global Biogeochemical Cycles 24(1): GB1002.

- Jiang ZP, Tyrrell T, Hydes DJ, Dai M, Hartman SE (2014) Variability of alkalinity and the alkalinity-salinity relationship in the tropical and subtropical surface ocean. Global Biogeochemical Cycles 28(7): 729-742.

-

Yaci Gallo Alvarez*, and Carlos Augusto Ramos e Silva. Total Alkalinity Calculations under International Thermodynamic Equation of Seawater changes. Ad Oceanogr & Marine Biol. 4(4): 2025. AOMB.MS.ID.000591.

-

Atlantic ocean; total alkalinity; salinity; sea water; water mass; iris publishers; iris publisher’s group

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.