Review Article

Review Article

The Proper Treatment of Pain and Chronic Pain, Artemisia Californica

James David Adams, Professor Emeritus, Benicia, CA, USA.

Received Date: November 24, 2021; Published Date: December 07, 2021

Abstract

Pain and chronic pain can be safely and effectively treated by applying a liniment to the skin made from Artemisia californica. The liniment contains monoterpenoids, sesquiterpenes and other compounds that penetrate into the skin, relieve pain and evaporate from the skin. The active compounds stop pain by inhibiting transient receptor potential cation channels and cyclooxygenase-2 in the skin. Chronic pain is cured by inhibition of skin chemokine, IL-17 and leukotriene production. Many patients have been treated with this liniment over the years. Many patients have been cured of chronic pain and opioid addiction with the liniment. The liniment is more effective than a placebo. The safety and efficacy of the liniment are contrasted to acupuncture, gabapentin, duloxetine and diazepam for chronic pain.

Keywords: Pain; Chronic pain; Pain Chemokine Cyclep Monoterpenoidsp Linimentp Artemisia Californica

Introduction

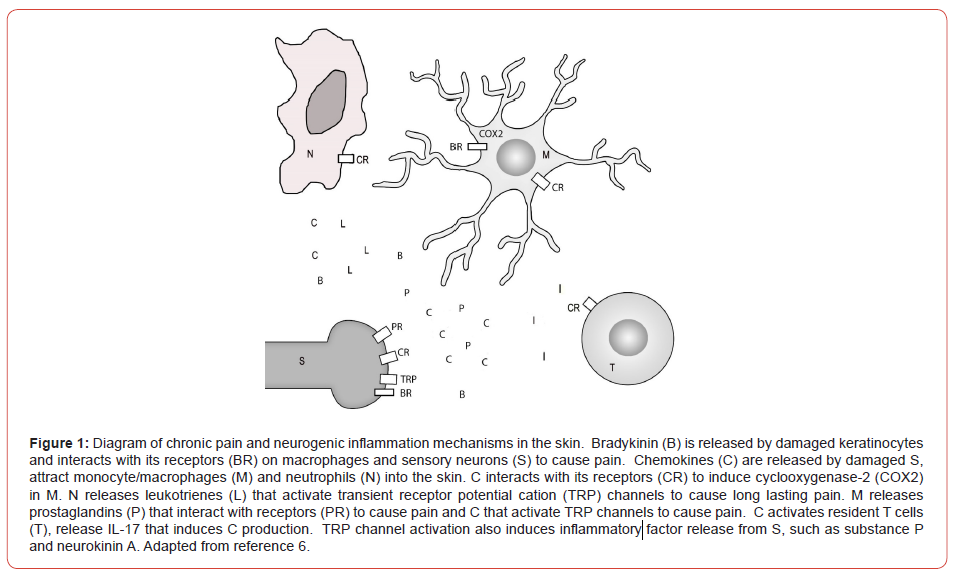

Pain is sensed in the skin by peripheral sensory neurons [1]. Even pain that results from problems deep in the body such as broken bones, heart attacks and cancer are sensed in the skin due to sensory neuron projections into the skin [2]. The major pain receptors in the body are transient receptor potential cation (TRP) channels found in the skin [1,3]. Therefore, the safest and most effective treatment of pain is by topical application of pain medicines to the skin [3]. Chronic pain is produced in the skin [4-6]. An initial painful insult causes sensory neurons to release chemokines that attract neutrophils and macrophages into the skin (Figure 1). Neutrophils secrete leukotrienes that activate TRP channels and cause long lasting pain. Macrophages express cyclooxygenase-2 (COX2), release prostaglandins that interact with prostaglandin receptors and activate TRP channels to cause pain. Macrophages also secrete chemokines that transactivate TRP channels. Chemokines cause the release of IL-17 from skin resident T cells. IL-17 stimulates the release of more chemokines and bradykinin [7]. The skin produces pain during chronic pain in a pain chemokine cycle. Neurogenic inflammation involves pain induced sensory neuron release of neurokinins, substance P and other inflammatory proteins that travel in the blood to induce inflammation. Bradykinin is released from epithelial cells, such as keratinocytes, after an initial insult and induces the release of neutrophil and monocyte chemotactic proteins [8]. Bradykinin receptors (B1 and B2) are expressed on monocytes, dendritic cells, sensory neurons and other cells [9]. Fibroblasts are activated by bradykinin and release inflammatory factors [10]. The activation of NFkB pathways by bradykinin results in chronic stimulation of inflammatory factor release [10], such as endothelin-1 [11]. Bradykinin initially causes the degranulation of mast cells, inflammation and edema [12]. This is followed by chronic release of inflammatory factors.

Prostaglandins increase the sensitivity of B2 receptors on sensory neurons to increase pain and inflammation [12]. Bradykinin increases the expression of chemokine receptors [13]. This enhances the pain chemokine cycle in chronic pain in the skin. Oral and injected pain medicines poison the body. The goal of oral therapy is to inhibit brain and brainstem opioid receptors and COX2. However, the brain and brainstem do not sense pain, but process pain. Drug penetration into the skin should be the real goal of pain therapy. Oral or injected drugs do not adequately penetrate into the skin to treat pain [3]. The use of opioids and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs results in the deaths of more than 100,000 patients yearly from seizures, respiratory depression, strokes, heart attacks and ulcers.

Many topical plant derived medicines are used around the world in the management of pain and chronic pain [3]. Some of these medicines, such as topical marijuana products, are becoming popular [14]. These plant medicines are not single purified agents but are a cocktail of pain medicines that work together to increase therapy.

Chumash Pain Therapy

The Chumash people of California were present when the Spanish first entered California in the 1760s. The Spanish were responsible for the deaths of many Chumash people due to child harvesting [15]. The Spanish would ride into a Chumash village, shoot and kill the men, rape the women and kidnap the children. This was called child harvesting. When the children were enslaved in the California missions, they were sometimes infected with gonorrhea by the priests. A teenage girl infected with gonorrhea may become infertile. Gonorrhea led to low birth rates in the missions. The Chumash people have for many years, made a liniment of a local plant, A. californica [16]. This liniment is used in the treatment of pain and chronic pain. Originally, the liniment was made from whale oil, which is no longer available. Fortunately, the Chumash people have shared the recipe for the liniment made in isopropanol [16].

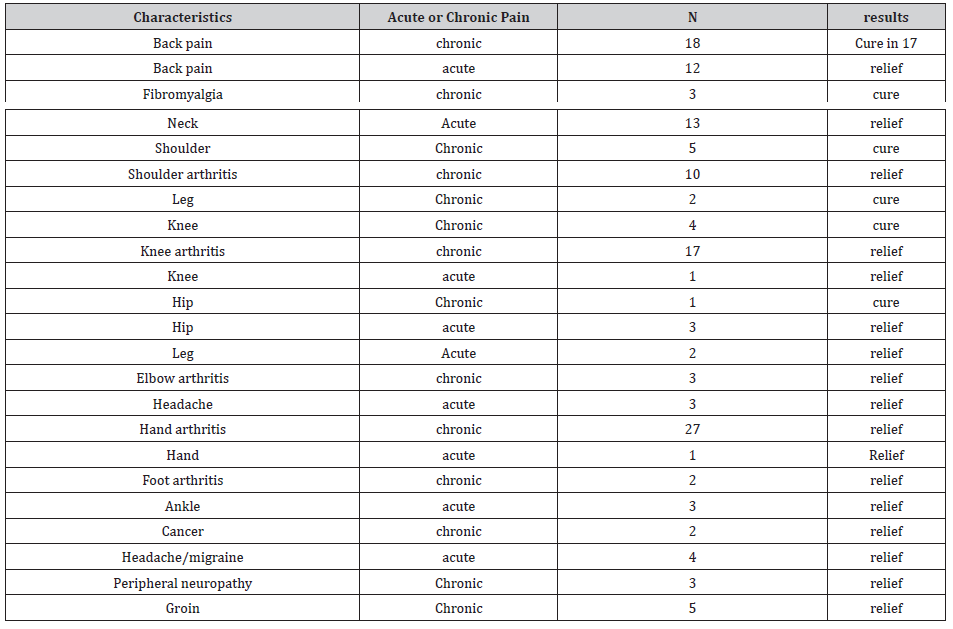

There are reports of many pain patients who were effectively and safely treated (Table 1) with A. californica liniment [17]. Several patients were cured of chronic pain such as fibromyalgia, whiplash and chronic back pain with the liniment [5]. This involves spraying the liniment onto painful areas every day for about 5 weeks. Several patients used the liniment to overcome opioid addiction [5]. This involves using the liniment daily to treat pain while decreasing opioid doses by half every week until the opioids are stopped. Many patients make the liniment themselves, for free, in order to treat their arthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, gout, peripheral neuropathy and other conditions. A. californica liniment is also anti-inflammatory by inhibition of neurogenic inflammation and other mechanisms [6,17-19].

Table 1: Patients treated with A. californica as reported in [5,17,20]. Chronic pain is pain of more than 1 month duration. Acute pain is from an injury or other acute event.

Chemistry and Pharmacology of A californica

Monoterpenoids are the major active ingredients in A. californica in terms of pain treatment [17, 18]. These compounds can penetrate into the skin, relieve pain and evaporate from the skin without having to penetrate into the blood to relieve pain. Camphene, menthadiene, β-pinene, eucalyptol, 4-isopropenyl- 1-methylcyclohexanol, 2,4,6-trimethyl- 1,6-heptadien-4-ol, isopropylmethyl bicyclohexanol, β-thujone, camphor, 3-thujanone, chrysanthenone, borneol, carene, menthenol and menthadienol were found in the plant. The major monoterpenoids present in the plant are eucalyptol (24%), camphor (18%), carene (14%) and menthadienol (9%). Camphene is used as a fragrance and food additive. It is a component of several essential oils form many different plants. Camphene is known to prenetrate into the skin [19], but its antinociceptive activity when applied to the skin has not been reported. It does have pain relieving activity when administered orally [17,18].

B-Pinene is the major smell from pine trees and is used as a food additive and fragrance. It has pain relieving activity when administered orally [17,18]. B-Pinene blocks TRP channels, including TRPM (possibly TRPM2/7) and TRPC (possibly TRPC6) channels [21] which relieves pain in the skin. It also appears to activate mu opioid receptors perhaps as a partial agonist [19,22]. Mu opioid receptors are found in the skin and elsewhere [1].

Eucalyptol also has pain relieving activity when administered orally and is present in many cough drops since it may soothe sore throats and decrease the urge to cough [17,18]. It inhibits TRPV3 and TRPM8 channels to relieve pain [17,18]. B-Thujone has a mint like smell and is present in absinthe. It has antinociceptive activity when administered orally and is an inhibitor of TRPV3 receptors [17,18]. Camphor is a food additive, fragrance, insect repellant, embalming fluid and is used in religious ceremonies. It is a common additive to pills, ointments and salves. It inhibits TRPV1, TRPV3 and TRPA1 receptors and is a pain reliever [17,18].

Menthadiene, 4-isopropenyl-1-methylcyclohexanol, 2,4,6-trimethyl- 1,6-heptadien-4-ol, isopropylmethyl bicyclohexanol, 3-thujanone, chrysanthenone, menthenol, menthadienol have not been investigated for pharmacological activity. It is not known if they relieve pain.

Sesquiterpenes are important in pain and chronic pain treatment [23-25]. A. californica contains several sesquiterenes [11], including leucodin, pestalodiopsolide A, echinolactone B, tanapartholide A and secogorgonolide. Leucodin decreases COX2 expression [23-25] which decreases pain and chronic pain. Anticancer activity has been reported for compounds similar to tanapartholide A. Many sesquiterpenes can penetrate into the skin after topical application and evaporate from the skin [23].

Flavonoids identified in A. californica are quercitin, quercitin glycoside, 6-methoxytricin and jaceosidin [17]. These compounds are anti-inflammatory. 6-Methoxytricin inhibits T cell activation [18] which may be important in IL-17 production in the skin. Jaceosidin penetrates into the skin after topical administration and inhibits the induction of nuclear factor kappa B to decrease inflammation [18]. Quercitin and quercitin glycoside inhibit tumor necrosis factor α and NO production to decrease inflammation [18]. They also activate serotonin (5HT-1A) receptors, which are found in the skin, to decrease pain [18]. Some flavonoids inhibit bradykinin receptors [26] to inhibit chronic pain and inflammation.

Liniment Efficacy and Safety

The approach of modern medicine to pain is by oral or injected medications. These medicines are dangerous poisons that must be abandoned. The topical treatment of pain can be more effective and much safer. The skin contains 28 different TRP channels that are the main pain sensors in the body [1]. Each of these channels responds differently to endocannabinoids, monoterpenoids and other agonist/antagonists. These channels are inhibited by tetrahydrocannabinol and cannabidiol when applied to the skin [1]. Monoterpenoids are much more potent than the cannabinoids at inhibiting TRP channels when applied to the skin [19]. There are many monoterpenoids in nature and many more synthetic monoterpenoids. These agents can be used to treat pain and cure chronic pain. It is important to use a cocktail of many monoterpenoids together. The single magic bullet approach does not work. Since each monoterpenoid may inhibit a different TRP channel, they synergize the pain-relieving qualities of each other. They have the quality of evaporating from the skin after providing pain relief. Penetration into the blood is not needed and avoids systemic toxicity.

Arthritis is an ongoing process of joint and bone degeneration. Inhibition of pain in sensory neurons provides anti-inflammatory therapy by inhibition of neurogenic inflammation [6] but does not cure arthritis. Patients who have used the liniment for their arthritis for several months usually report their inflammation is somewhat alleviated. Chronic pain is generated in the skin. The cure of chronic pain requires topical medicines that penetrate into the skin and inhibit the pain chemokine cycle. Opioids make chronic pain worse by inducing chemokine production [27]. This is especially true of fentanyl patches that can cause opioid induced hyperalgesia within one day [28,29].

Curing chronic pain can be done by inhibiting the production of IL-17 or chemokines in the skin [4-6]. Application of salicylates, which are monoterpenoids, to the skin inhibits cyclooxygenase-2 production of prostaglandins but does not cure chronic pain. A cocktail of monoterpenoids, diterpenoids and perhaps other compounds such as with the liniment reported here provides an effective way to treat acute pain and cure chronic pain [4-6].

Acupuncture for Chronic Pain

Acupuncture treats pain in the skin. This appears to involve inhibition of TRP channels on sensory neurons [1]. Safety of acupuncture is well known. The only safety issue is when acupuncture needles are permanently embedded into the skin. This can lead to infections and allergic reactions. A recent metaanalysis of acupuncture in 20,827 chronic pain patients, including osteoarthritis patients [30] found that acupuncture is superior to placebo. The effects of acupuncture in chronic pain treatment are consistent from treatment to treatment over time, with only a 15% decrease in efficacy over time. Initial pain was about 6 out of 10 and decreased to 3.5 with placebo acupuncture and 3 with acupuncture. Acupuncture does not cure chronic pain but is an effective, safe treatment.

Gabapentin For Chronic Pain

Gabapentin is a very popular medicine for chronic pain and is the 11th most widely prescribed medicine in the US [31]. The drug inhibits voltage gated calcium channels by binding to the α2δ subunit. Gabapentin penetrates into the skin and is used to treat pruritis. However, a clinical trial of post-operative chronic pain found that gabapentin did not decrease the duration of pain [31]. Neuropathy is effectively treated by oral gabapentin with response rates of 32-38% of patients reporting some pain relief compared to 17-23% for placebo [32]. Topical preparations of gabapentin are available and have been tested in a few patients [33, 34]. For neuralgia and vulvodynia, pain relief begins within 5 minutes and lasts about 3 h. There are no reports of toxicity from topical gabapentin.

Oral gabapentin is addictive, a substance of abuse, and is sold on the streets for abuse [35]. It causes euphoria and a mild experience described as similar to marijuana. It also causes death from respiratory depression, automobile accidents and perhaps suicide [36]. Pregabalin is similar to gabapentin in pharmacology and toxicity. It is used for fibromyalgia [37]. It relieves pain in many patients but does not cure fibromyalgia. Topical pregabalin has been found to provide pain relief in peripheral neuropathy but is not recommended in place of oral agents [38]. The safety of topical pregabalin compared to oral pregabalin should argue for the use of topical pregabalin.

Duloxetine for Chronic Pain

Duloxetine is used for chronic back pain and other chronic pain issues. It is a serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor with antidepressant activity. Its mechanism of action against chronic pain is not known. A study of chronic back pain found pain decreased at week 14 by 2.4 out of 10 with duloxetine compared to 2.0 for placebo [39]. A Cochrane analysis found that duloxetine decreases pain in diabetic neuropathy and fibromyalgia, without curing chronic pain [40]. Duloxetine is considered a safe medicine but can produce seizures and the serotonin syndrome in overdose.

Carbamazepine for Chronic Pain

Carbamazepine is a sodium channel blocker. It has been found to provide pain relief in trigeminal neuralgia, diabetic neuropathy and post stroke pain [41]. It decreases the production of red and white blood cells, increases suicide and is toxic to fetuses. It is occasionally used as a drug of abuse. Topical carbamazepine has not been tested against chronic pain.

Diazepam for Chronic Pain

Diazepam is a benzodiazepine, addictive, has a long duration of action and is used against anxiety, seizures and other problems [42]. It is a positive allosteric modulator of GABAA receptors. The use of diazepam in chronic pain makes patient outcomes worse in terms of pain, fear and disability [42]. In fact, diazepam was worse than morphine in terms of outcomes in chronic pain.

Conclusions

Topical preparations of monoterpenoid combinations provide excellent pain relief and can cure chronic pain other than arthritis. There should be clinical trials of these preparations. It is very possible these liniments could improve patient’s lives and decrease patient deaths from dangerous oral drugs.

Acknowledgement

None.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest.

References

- Adams J (2016) The effects of yin, yang and chi in the skin on pain. Medicines 3(1): 5.

- Zhang Y, Zhao S, Rodriguez E, Takatoh J, Han B, et al. (2015) Identifying local and descending inputs for primary sensory neurons. J Clin Invest 125(10): 3782-3794.

- Adams J, Wang X (2015) Control of pain with topical plant medicines. Asian Pac J Trop Biomed 5: 930-935.

- Adams J (2017) Chronic pain can it be cured? J Pharmaceut Drug Devl 4: 105-109.

- Adams J (2018) Chronic pain two cures. OBM Integ Comp Med: 3.

- Adams J (2019) Chronic pain in the skin, sexual differences and neurogenic inflammation. J Altern Complement Integr Med 5: 073-075.

- Mandy J McGeachy, Daniel J Cua, Sarah L Gaffen (2019) The IL-17 Family of Cytokines in Health and Disease. Immunit 50(4): 892-906.

- Koyama S, Sato E, Nomura H, Kubo K, Miura M, et al. (1998) Bradykinin Stimulates Type II Alveolar Cells to Release Neutrophil and Monocyte Chemotactic Activity and Inflammatory Cytokines. Am J Pathol, 153(6): 1885-1893.

- Marketou M, Kontaraki J, Zacharis E, Parthenakis F, Maragkoudakis S, et al. (2014) Differential gene expression of bradykinin receptors 1 and 2 in peripheral monocytes from patients with essential hypertension. J Human Hypertension 28: 450-455.

- Falsetta M, Foster D, Woeller C, Pollock S, Bonham A, et al. (2016) A Role for Bradykinin Signaling in Chronic Vulvar Pain. J Pain 17(11): 1183-1197.

- Yoshino O, Yamada-Nomoto K, Kobayashi M, Andoh T, Hongo M, et al. (2018) Bradykinin system is involved in endometriosis-related pain through endothelin-1 production. Eur J Pain 22(3): 501-510.

- Paterson K, Zambreanu L, Bennett D, McMahon S (2013) Characterisation and mechanisms of bradykinin-evoked pain in man using iontophoresis. Pain 154(6): 782-792.

- Eddleston J, Christiansen S, Jenkins G, Koziol J, Zuraw B (2003) Bradykinin increases the in vivo expression of the CXC chemokine receptors CXCR1 and CXCR2 in patients with allergic rhinitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 111(1): 106-112.

- Garg G, Adams J (2012) Treatment of neuropathic pain with plant medicines. Chin J Integr Med 18: 565-570.

- Adams, J, Phipps, T (2018) Los Angeles Indian labor practices after the Civil War. J West 57: 60-71.

- Adams J, Wong M, Villasenor E (2020) Healing with medicinal plants of the west – cultural and scientific basis for their use fourth edition. Abedus Press: La Crescenta, USA.

- Fontaine P, Wong V, Williams T, Garcia C, Adams J (2013) Chemical composition and antinociceptive activity of California sagebrush (Artemisia californica). J Pharmacog Phytother 5: 1-11.

- Adams J (2012) The use of California sagebrush (Artemisia californica) liniment to control pain. Pharmaceuticals 5: 1045-53.

- Perri F, Coricello A, Adams J (2020) Monoterpenoids: the next frontier in the treatment of chronic pain? J Multidisc Sci J 3: 195-214.

- Adams, J, Villasenor, E, Guhr, S (2020) Pain patients prefer Artemisia californica liniment to placebo in a community based trial. Int J Ther 37: 47-50.

- Schepetkin I, Kushnarenko S, Özek G, Kirpotina L, Sinharoy P, et al. (2016) Modulation of Human Neutrophil Responses by the Essential Oils from Ferula akitschkensis and their Constituents. J Agric Food Chem 64: 7156-70.

- Liapi C, Anifandis G, Chinou I, Kourounakis A, Theodosopoulos S, et al. (2007) Antinociceptive properties of 1,8-Cineole and beta-pinene, from the essential oil of Eucalyptus camaldulensis leaves, in rodents. Planta Med 73: 1247-1254.

- Coricello, A, Adams, J, Lien, E, Nguyen, C, Perri, F, et al. (2020) Walk in Nature. Sesquiterpene Lactones as Multi-Target Agents Involved in Inflammatory Pathways. Curr Med Chem 27: 1501-1514.

- Coricello A, El-Magboub A, Luna M, Ferrario A, Haworth I, et al. (2018) Rational drug design and synthesis of new a-Santonin derivatives as potential COX-2 inhibitors. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 28: 993-996.

- Perri F, Frattaruolo L, Haworth I, Brindisi M, El-magboub A, et al. (2019) Naturally occurring sesquiterpene lactones and their semi-synthetic derivatives modulate PGE2 levels by decreasing COX2 activity and expression. Heliyon 5: e01366.

- Yun-Choi H, Chung S, Kim Y (1993) Evaluation of some flavonoids as potential bradykinin antagonists. Arch Pharmacal Res 16: 283-288.

- Rogers T (2020) Bidirectional Regulation of Opioid and Chemokine Function. Front Immunol 11: 94.

- Mélik Parsadaniantz S, Rivat C, Rostène W, Réaux-Le Goazigo A (2015) Opioid and chemokine receptor crosstalk: a promising target for pain therapy? Nature Rev Neurosci 16: 69-78.

- Lyons P, Rivosecchi R, Nery J, Kane-Gill S (2015) Fentanyl-induced hyperalgesia in acute pain management. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother 29(2): 153-60.

- Vickers J, Vertosick E, Lewith G, MacPherson H, Foster N, et al. (2018) Acupuncture for chronic pain: update of an individual patient data meta-analysis. J Pain 19(5): 455-474.

- Hah J, Mackey S, Schmidt P, McCue R, Humphreys K, et al. (2018) Effect of Perioperative Gabapentin on Postoperative Pain Resolutionand Opioid Cessation in a Mixed Surgical Cohort a Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Surg 153(4): 303-311.

- Puljak L (2020) Can Gabapentin Alleviate Chronic Neuropathic Pain in Adults? A Cochrane Review Summary with Commentary. Am J Physical Med Rehab 99: 558-559.

- Brid T, Sacristán de Lama M, González M, Baamonde A (2017) Topical Gabapentin as Add-on Therapy for Trigeminal Neuralgia. A Case Report. Pain Med 18: 1824-1826.

- Boardman L, Cooper A, Blais L, Raker C (2008) Topical Gabapentin in the Treatment of Localized and Generalized Vulvodynia. Obstet Gynecol 112: 579-585.

- Smith R, Havens J, Walsh S (2016) Gabapentin misuse, abuse, and diversion: A systematic review. Addiction 111(7): 1160–1174.

- Tharp A, Hobron K, Wright T (2019) Gabapentin-related Deaths: Patterns of Abuse and Postmortem Levels. J Forensic Sci 64(4): 1105-1111.

- Attal N, Cruccu G, Baron R, Haanpää M, Hansson P, et al. (2010) EFNS guidelines on the pharmacological treatment of neuropathic pain: 2010 revision. Eur J Neurol 17: 1113–1123.

- Sommer C, Cruccu G (2017) Topical Treatment of Peripheral Neuropathic Pain: Applying the Evidence. J Pain Symptom Manage 53: 614-629.

- Konno S, Oda N, Ochiai T, Alev L (2016) Randomized, Double-blind, Placebo-controlled Phase III Trial of Duloxetine Monotherapy in Japanese Patients With Chronic Low Back Pain. Spine 41: 1709-1717.

- Lunn M, Hughes R, Wiffen P (2014) Duloxetine for treating painful neuropathy, chronic pain or fibromyalgia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (1): CD007115.

- Wiffen P, Derry S, Moore R, Kalso E (2014) Carbamazepine for chronic neuropathic pain and fibromyalgia in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 4: CD005451.

- Gauntlett-Gilbert J, Gavriloff D, Brook P (2016) Benzodiazepines May be Worse Than Opioids: Negative Medication Effects in Severe Chronic Pain. Clin J Pain 32(4): 285-91.

-

James David Adams. The Proper Treatment of Pain and Chronic Pain, Artemisia Californica. Arch Neurol & Neurosci. 12(1): 2021. ANN.MS.ID.000776. DOI: 10.33552/ANN.2021.12.000776

-

Pain; Chronic pain; Pain Chemokine Cyclep Monoterpenoidsp Linimentp Artemisia Californica

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Chumash Pain Therapy

- Chemistry and Pharmacology of A californica

- Liniment Efficacy and Safety

- Acupuncture for Chronic Pain

- Gabapentin For Chronic Pain

- Duloxetine for Chronic Pain

- Carbamazepine for Chronic Pain

- Diazepam for Chronic Pain

- Conclusions

- Acknowledgement

- Conflict of Interest

- References