Research Article

Research Article

Sleep Quality and its Lifestyle Associated Factors among Secondary School Students in an Egyptian City

Dalia G Mahran1*, Dalia M Ismail1, Ali H Zarzour1 and Ghaydaa Shehata2

1Department of Public Health and Community Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Assiut University, Egypt

2Department of Neurology and Psychiatry, Faculty of Medicine, Assiut University Hospital, Egypt

Dalia G Mahran, Professor, Department of Public Health and Community Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Assiut University, Egypt.

Received Date: October 21, 2021; Published Date: November 12, 2021

Abstract

Introduction: sleep is critically important to human being as it can properly maintain mental and physical health.

Study objectives: to determine the predictors of poor sleep quality among secondary school students in Egyptian city.

Material and Methods: a cross sectional study was conducted among secondary school students in Assiut. students were selected randomly by multistage stratified random sampling technique Data was collected using a self-administered questionnaire that included demographic data, Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), lifestyle factors associated with poor sleep quality.

Results: The prevalence of poor sleep among participants was 72.5%. poor sleep quality was more prevalent among females, public school students, urban residents and male students who use illicit drugs. Significant Correlates of poor sleep quality by multivariate analysis were urban residence, using illicit drugs, using internet and mobile phones, irregular breakfast and dinner taking, regular eating carbohydrate and snacks, drinking caffeinated drinks and daytime napping.

Conclusions: poor sleep quality was critically important problem among secondary school student with many lifestyle factors as using illicit drugs, using internet and mobile phones for long time, irregular breakfast and. Dinner time, caffeinated drinks after 6pm and day time napping. Increasing the awareness about healthy sleep is an essential priority especially by focusing programs on adolescents with lifestyle risk factors.

Keywords: Sleep quality; Lifestyle correlates; Secondary schools

Abbreviations: PSQI: Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index

Introduction

Sleep is a critically important to human being as it can properly

maintain mental and physical health. Good quality of sleep helps

in cognitive restitution, learning, decision making, memory

consolidation and processing of an individual [1,2]. Previous

studies have found that poor sleep has associated with weight gain,

obesity, daytime sleepiness, exhaustion, impaired glucose tolerance

and diabetes, depression and anxiety, impaired memory, and higher

risk of motor vehicle accidents [3-8].

Adolescents’ aged between 10-19 years old suffering poor

sleep quality is a major worldwide concern [9]. The recommended

sleep duration for adolescents is between eight to ten hours of

sleep per night in order they could to function well [10]. The

transition from childhood to adolescents mostly happens during

their schooling environment. During this transition period several

biological, physical and psychological aspects of changes will

occur to the adolescent. During this period the adolescents suffer

from increasing pressures from family, school, social and even

the environmental that indirectly contribute towards the delay in

sleep timing together with a biological sleep phase delay causing

poor sleep quality [11]. Adolescents experience rigid early school

start times, elevated social and academic demands, and increased exposure to electronic media, all of which contribute to poor sleep

quality [12]. Reduction in sleep quality and sleep duration across

populations was found to be linked to increased social and work

demands, changes in lifestyle, smoking, alcohol, increasing use

of technology, current sexual activity, dietary factors, caffeine

intake and level of physical activity [13-20]. This study aimed to

determine the predictors of poor sleep quality among secondary

school students in Assuit, Egypt. The findings from this study

will add new knowledge in the respective field and will provide

useful information for the government or policymakers in terms

of planning an intervention or a campaign targeting the secondary

school students by focusing on the significant predictors of poor

sleep quality of this study. Hence, it will give a wake-up call for

better health and wellbeing for the future generation.

Materials And Methods

A cross sectional study was conducted among 829 secondary school students selected in their second year.

Sample size

Sample size was calculated using Epi- Info, version 7 for descriptive study design. according to the student affairs administration in education high authority, the total number of registered students in the second year of secondary school was. 7,686 students. Based on the least prevalence of poor sleep quality in adolescents from other studies. The calculated number was 375 students. In this study, a multistage stratified random sampling technique was used to select the study sample to correct for the difference in design the sample size was multiplied by the design effect (2); the result equaled 750. An increase in the sample by 10% is used to account for incomplete questionnaires and non responders; the final calculated sample was 825 students.

Sample design

The target students were selected randomly by multistage stratified random sampling technique. Firstly, the schools were stratified into public, private, and technical secondary schools, with further stratification into boys’ and girls’ schools. From every stratum one school was randomly selected, thereby giving a total of four boys’ schools and four girls’ schools. Out of public schools’ strata two schools were selected to include different city regions. Secondly, according to the number of students in the second year in every secondary school, the total sample size was divided proportionately. Lastly, by using simple random sampling the classes were selected. In every class, all students All students were included. Those students who refused to participate were few in number.

Data collection tool and technique

A self-administered questionnaire was used in data collection. The data included the following: (a) demographic data of the students; (b) sleep quality, using the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI); (c) lifestyle factors associated with poor sleep quality.

The demographic variables were categorized as follows: sex (male and female), residence (rural and urban), type of education (public, private, and technical), smoking (nonsmoker, currently smoker, and ex-smoker) and addiction (using illicit drugs and no). The PSQI is a questionnaire that is used to evaluate sleep quality over the last month; it is a validated questionnaire that has been used to evaluate sleep quality of adolescents and young adults. It consists of 19 self-rated questions that are grouped into seven component scores, all of which have equal weight on a 0–3 scale. These components are sleep latency, sleep duration, subjective sleep quality, habitual sleep efficiency, daytime dysfunction, sleep disturbances and use of sleep medication. The seven component scores are summed to give a global PSQI score from 0 to 21; a higher score indicates worse sleep quality. A score more than 5 differentiates between good and bad sleep quality, with a sensitivity of 89.6% and specificity of 86.5%.The internal consistency of the index (Cronbach’s α = 0.83). The index needs 5 to 10 min to complete [21]. Suleiman et al. (2010) [22] translated the questionnaire into Arabic.

Lifestyle factors associated with poor sleep quality were categorized as follows: watching TV and using internet (not regularly, less than one hour per day, one hour per day, two hours per day, 3-4 hours per day and 5 hours or more per day), using mobile phones (calls/text messages) (zero, less than one hour per day, one to > 2 hours per day and ≥2 hours per day), sleeping with lights on, daytime napping and using bed for activities other than sleep (always, usually, sometimes and never), eating breakfast, lunch, dinner, snacks, vegetables and fruits, milk, carbohydrates and caffeinated drinks after 6 pm (regular and irregular). Data collection was done away from the exam times at the middle of the first semester of academic year. The questionnaire was filled in by the students during class. It was explained page by page. In every class, the class teacher and two well-trained data collectors assisted in watching the students and keeping understanding and completeness of data during questionnaire filling in.

Data management and statistical analysis

The study hypothesis was “poor sleep quality would be

associated with many demographic, lifestyle factors and special

habits that could be risk factors for poor sleep quality”.

Descriptive statistics were used in the form of frequencies,

means, and standard deviations [SDs] also tests of significance such

as the chi-square test and Fisher’s Exact test for qualitative variables

and Student’s t test for quantitative variables. For prediction of

factors that could be associated with poor sleep quality binary

logistic regression analysis was used. All significant factors that

were found to be likely associated with poor sleep quality by using

bivariate analysis were used to construct regression models. Only

significant variables included in the final equation. P-value was

considered significant when it was equal to or less than 0.05.

Ethical considerations

Before starting data collection, the proposal was approved by the Faculty Ethical Review Committee in Assiut university. Also, an approval was received from the Central Agency of Public Mobilization and Statistics and administration of secondary education and directors of every school. After explanation of the aim and methods of the study, an informed consent was taken from every student. As the questionnaire items did not include sensitive issues, parents’ consent was not sought, and it was not requested from the higher authorities. It was explained at the class that the collected data will be used for scientific research only and are confidential.

Results

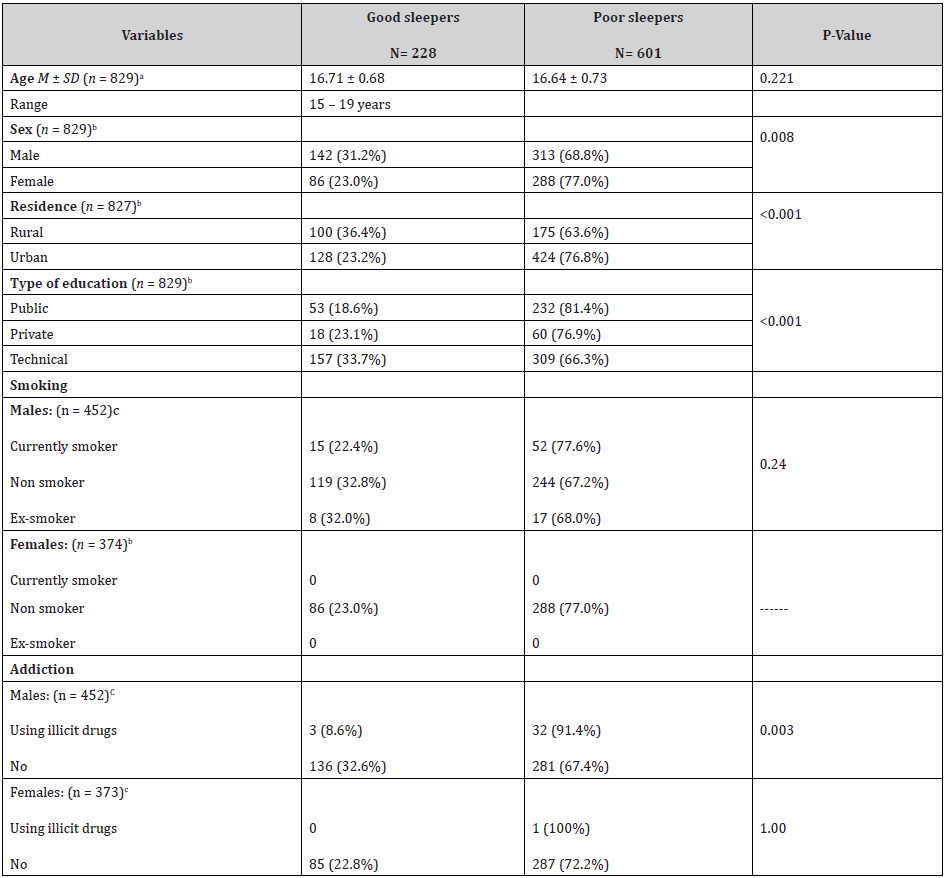

The mean age of the students was 16.66 ± 0.72 SD. About one half (54.9%) were boys, 56.2% attended technical schools, 66.7% were from urban areas, 14.7% of males were currently smokers, 7.7% of males reported using illicit drugs as hashish or bango. The prevalence of poor sleep among participants was 72.5%, using the cut off of PSQI >5. The mean PSQI score was 7.35 (SD = 2.94). Poor sleepers were statistically significantly higher among females (77.0%) than males (68.8%). Urban residents (76.8%) evidenced poorer sleep compared to rural residents (63.6%). The percent of poor sleepers was higher among public school students (81.4%) than private school students (76.9%). The percent of poor sleepers was statistically significantly higher among male students who use illicit drugs (91.4%) than non-users (67.4%) of illicit drugs (Table 1).

Table 1: Relationship between demographic factors & special habits and sleep quality among secondary school students in Assiut city, 2015.

aStudent’s t test was used. bChi-square test was used. c Fisher’s Exact test was used.

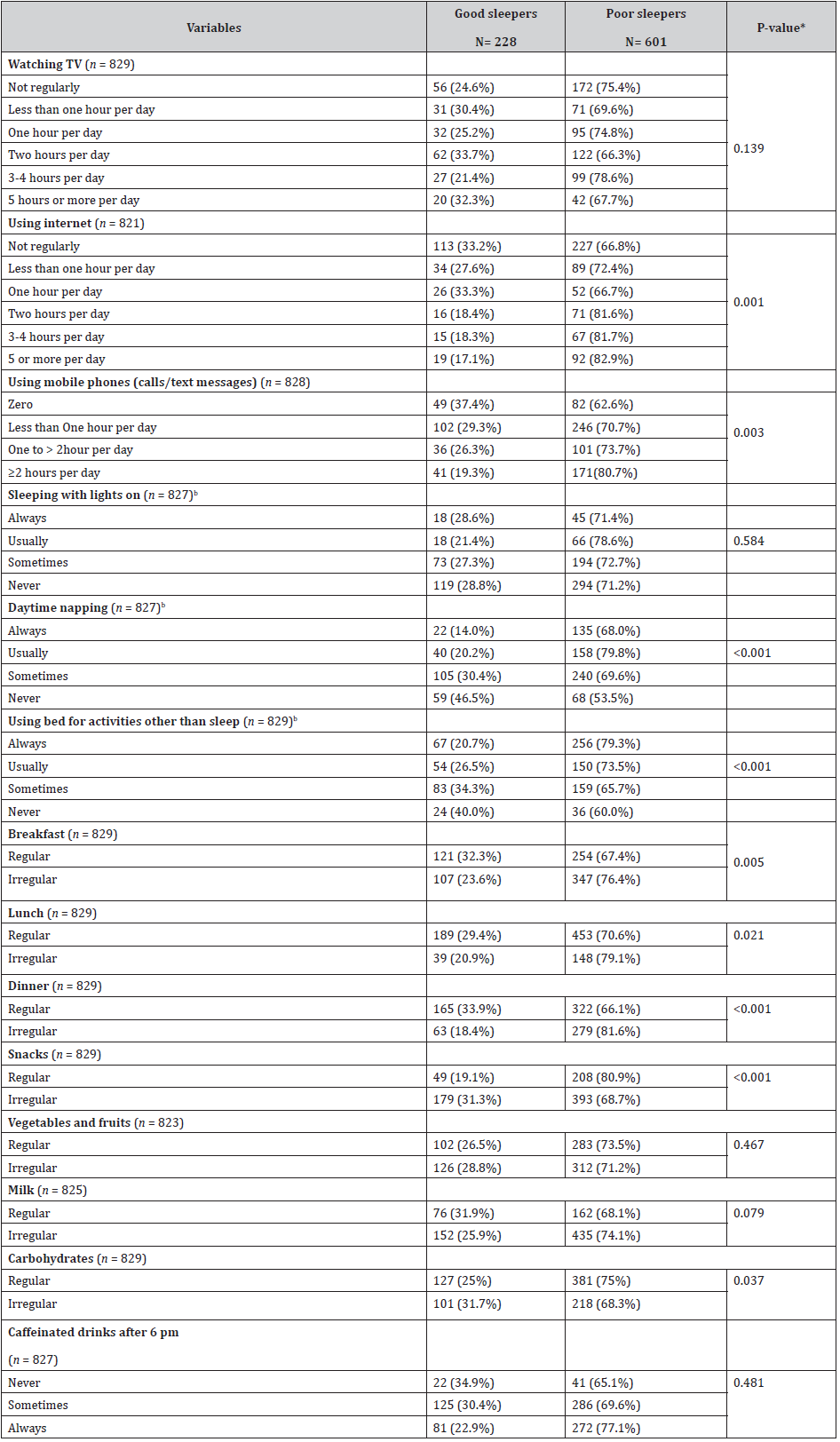

The percent of poor sleepers was the highest among students who were usually taking sleep naps (79.8%), and the lowest among students who were never taking sleep naps (53.5%). In addition, the percent of poor sleepers was highest among students who were always using bed for activities other than sleep (79.3%), and the lowest among students who were never using bed for activities other than sleep (60.0%). The percent of poor sleepers was the highest among students who reported using internet 5 hours or more per day (82.9%), and the lowest among students who reported using internet one hour per day (66.7%), the association was statistically significant (p=0.001). Also, the percent of poor sleepers was the highest among students who reported using mobile phones 2 hours or more per day (80.7%), and the lowest among students who reported no using mobile phones (62.6%), the association was statistically significant (p=0.003). On the other hand, there was no statistical significant association between sleep quality and watching TV, using computer or video games.

Regarding the percent of poor sleepers was higher among students who eat breakfast, lunch and dinner irregularly (less than 5 days per week) 76.4%, 79.1% and 81.6% respectively compared to 67.4%, 70.6% and 66.1% among students who eat breakfast, lunch and dinner regularly, the associations were significant (p<0.05). Also, the percent of poor sleepers was higher among students who eat snacks and carbohydrates regularly (less than once every day) 80.9% and 75.0% respectively compared to 68.7% and 68.3% among students who eat snacks and carbohydrates irregularly, the associations were significant (p<0.05). The percent of poor sleepers was higher among students who reported always drinking caffeinated drinks after 6 pm (77.1%) compared to (65.1%) among students who reported never drinking caffeine containing drinks after 6 pm (p < 0.05; Table 2)

Table 2: Relationship between lifestyle factors and sleep quality among secondary school students in Assiut city, 2015.

*Chi-square test was used

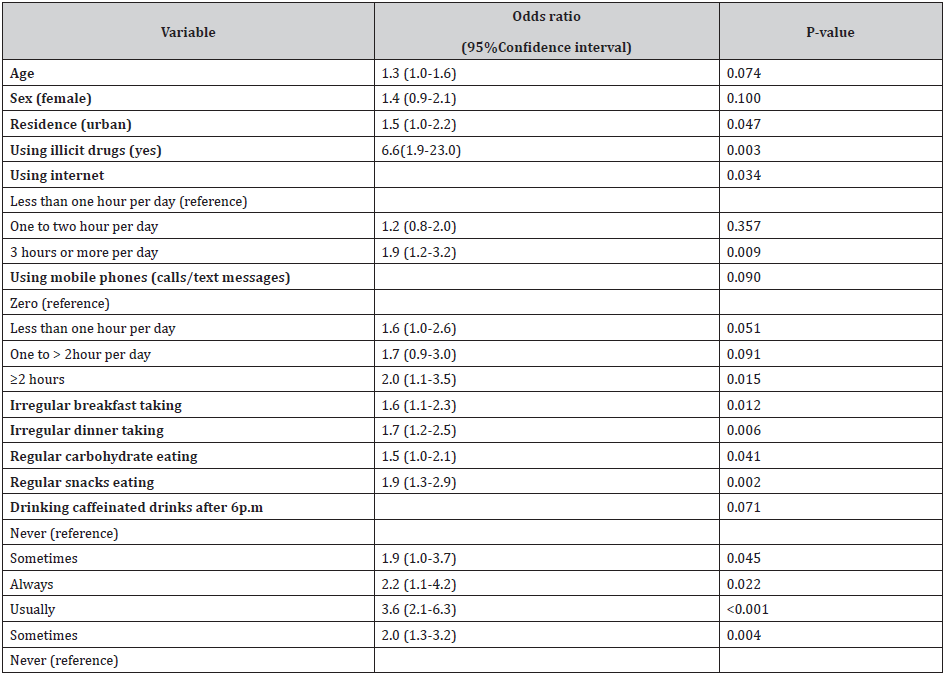

Table (3) presents multivariate logistic regression, the significant predictors of poor sleep were: the chance of poor sleep increased 1.5 times among urban residents compared to rural residence [odds ratio (OR) 1.5, 95% confidence interval (CI) (1.0 - 2.2) P=0.047]. Using illicit drugs regular or sometimes has shown significant increase in the chance of poor sleep quality 6.6 times compared to not using it [OR 6.6, CI (1.9-23.0) p=0.003]. The chance of poor sleep increased 1.9 times with using internet three hours or more per day compared to using internet less than one hour per day [OR 1.9, CI (1.2-3.2) p=0.009]. Also, using mobile phones two hours or more per day has shown significantly increasing the chance of poor sleep quality two times compared to not using mobile phones [OR 2.0, CI (1.1-3.5) p=0.015]. Also, irregular breakfast taking (less than five days per week) has shown significantly increasing the chance of poor sleep quality 1.6 times compared to regular breakfast taking [OR 1.6, CI (1.1-2.3) p=0.012]. Also, irregular dinner taking (less than five days per week) has shown significant increase in the chance of poor sleep quality 1.7 times compared to regular dinner taking [OR 1.7, CI (1.2-2.5) p=0.006]. Also, regular eating carbohydrate (once or more per day) has shown significant increase in the chance of poor sleep quality 1.5 times compared to irregular eating carbohydrate with [OR 1.5, CI (1.0-2.1) p=0.041]. Also, regular eating snacks (once or more per day) has shown significant increase in the chance of poor sleep quality 1.9 times compared to irregular eating snacks with [OR 1.9, CI (1.3-2.9) p=0.002]. Also, always drinking caffeinated drinks after 6p.m has shown significant increase in the chance of poor sleep quality 1.9 times compared to never drinking caffeine containing drinks after 6p.m [OR 1.9, CI (1.0-3.7) p=0.045]. Also, always daytime napping has shown significant increase in the chance of poor sleep quality 4.8 times compared to never daytime napping [OR 4.8, CI (2.6-9.0) p>0.0001].

Table 3: Predictors of Poor Sleep Quality Among Secondary School Students in Assiut, 2015 Identified by Multivariate Logistic Regression Analysis

N = 808. Nagelkerke R Square = 0.21. Odds ratio is adjusted for all variables in the table.

Discussion

This study was a cross-sectional study. It was conducted to identify the associated factors which may lead to poor sleep quality. In the current study, age was significant predictor of poor sleep quality [OR 1.4, p=0.014]. This is consistent with the results of meta-analysis of 41 surveys worldwide conducted by Gradisar et al. [23]. Age is important factor affecting sleep pattern in adolescents as it leads to delay of sleep time and restrict school night sleep [23]. The effect of age (especially adolescence) on sleep is attributed to developmental changes in the circadian alerting system, so the preferred times for falling asleep and waking are typically delayed in adolescents [24]. The delayed sleep time during adolescence, early school start time and increased academic and social demands lead to poor sleep.

In the current study, poor sleep quality was associated with female gender. The prevalence of poor sleep quality was higher among females than males with statistical significant difference (p=0.008). This difference may be attributed to that females are more subjected to anxiety, depression and long periods of thinking [25]. This is consistent with the results of many studies. Merdad et al., 2014 in the Saudi study in Jeddah among 947 high school students aged 14–23 years found that females has significantly higher PSQI than males [12]. Similar results were found among 1,629 Hong Kong Chinese adolescents aged 12 to 19 years [9]. In Japanese study among 94,777 adolescents, it was also reported that female adolescents had more short sleep duration than males and more female adolescents rated their sleep quality as poor or very poor [26].

In the current study, the prevalence of poor sleep quality was higher among residents of urban area with statistical significant difference (p>0.0001). Using logistic regression, the chance of poor sleep increased two times among urban residents compared to rural residence [OR 2.0, p=0.002]. This finding may be due to calm green environment, early closure of services in rural areas and more access of the adolescents to internet and new technology in urban areas that allows better sleep quality. This result is comparable with the results of study made by Liu et al., 2008 among 1056 high school students in China who found that urban students go to bed later than rural students [27]. This is also consistent with the findings of Haseli-Mashhadi et al., 2009 that rural residents were more likely to report good levels of sleep quality compared to urban residents in middle-aged and elderly Chinese [28].

In the current study, we found that technical school students

were less liable to poor sleep than public and private school

students with a highly statistical significant difference (p>0.0001).

In multiple analysis, the chance of poor sleep increased 1.8 times

among public education students compared to technical education

students [OR 1.8, p=0.023]. This finding may be related to the lower

socioeconomic level of technical school students, less access to new

technology, more physical activity and less napping due to more

afternoon jobs. All these factors lead to better night sleep. This

finding could be explained also by the fact that majority of technical

schools students are residents of rural areas.

This study found that the percent of poor sleepers was higher

among smoker males than non-smoker males (77.6% versus 67.2%

respectively), but the association was not statistically significant.

The previous studies showed different results about association

between sleep and smoking. Cheng et al., 2012 found no statistical

significant difference between good and poor sleepers (PSQI

score≥6) as regarding smoking among 4,318 incoming university

students in Taiwan [29]. The same results were found among 1,515

African Americans, aged 30-65 years, [30] and 2,803middle aged

Chinese [31]. On the other hand, a study among 12,154 high school

students in USA [16] and other study among 2,432 Norwegian

adolescents, aged 15-17 years [32], revealed that being a current

smoker increased the odds of sleeping < 8hours. Additionally

smoking was found as a risk factor for sleep problems in Japanese

[33] and Hong Kong studies [9]. Although the results of the studies

differs between significant and non-significant association between

different sleep measures and smoking but being a current smoker a

bad habit was related to poor sleep measures in most studies. The

effect of smoking on sleep is attributed to nicotine stimulation of

nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in the brain that results in release

of a variety of neuro-transmitters in the brain, most importantly

dopamine. Based on these effects nicotine could interact with sleep

regulating mechanisms and may affect sleep quality or Rapid Eye

Movement sleep [34].

This study found that the percent of poor sleepers was higher

among male students who used illicit drugs regularly or sometimes

compared to non-users of illicit drugs with statistical significant

difference (p=0.003). By using logistic regression, using illicit

drugs regular or sometimes has shown significant increase in the

chance of poor sleep quality 6.6 times compared to non users [OR

6.6, p=0.003]. Despite the presence of such significant relation, this

point could not be analyzed as only 35 students reported using

illicit drugs and many students who use illicit drugs would deny

addiction, so this relation would be studied with other study means

as e-mail or phone. This result is consistent with other studies in

USA (16) and Norway [32].

In this study, it was found that using internet was a significant

risky behavior associated with poor sleep quality (p=0.001), by

using multiple regression, using internet three hours or more per

day was a significant predictor of poor sleep [OR 1.9, p=0.009].

This relation is mostly due to increase the alertness and level of

activity of the nervous system. Also exposure to the bright light

of the viewing screen before sleep may affect the sleep/wake

cycle through suppression of the nocturnal salivary secretion

of melatonin. In addition, the content of television programs

and computer game playing may be excessively violent and/or

stimulating, which may inhibit relaxation and result in anxiety and

difficulty in falling asleep [19, 35]. This finding is in agreement

with many studies, as that was conducted among 1,956 Turkish

high school students aged between 14 and 18 years which found

that the students with internet addiction (using Internet Addiction

Test) were more likely to have difficulty in falling asleep and night

awakenings, problematic internet users and internet addicts were

found to sleep significantly less than average internet users [36].

Another Taiwanese study found that poor sleep quality (PSQI score

≥6) was significantly associated with a higher tendency toward

internet addition [29]. In a study, among 2,546 Belgium secondary

school children, adolescents who spent more time using the

internet went to bed significantly later during the week and during

the weekend, got up later on weekend days and spent less time in

bed during the week [18].

In the current study, there was significant inverse relation

between sleep quality and hours of using mobile phones (p=0.003).

By multiple analysis, using mobile phones two hours or more

per day was significant predictor of poor sleep quality [OR 2.0,

p=0.015]. This relation is consistent with a study; done in UK

among 738 adolescents aged 11–13 years, that found that frequent

use of mobile phones was associated with difficulty in falling asleep,

frequent early awakening and inversely associated with weekday

sleep duration [37]. Also the study, conducted by Yang et al., 2010

among 11,111 Taiwanese adolescents aged 12-18 years, found

that problematic cell phone use was associated with insomnia in

adolescents [38]. While the study, conducted by White et al., 2011

among 350 college students with average age 20 years in USA,

found that mobile phone use was related to sleep quality, but not

sleep length [39].

On the other hand, the current study found that there was

no statistical significant association between sleep quality and

frequency of watching TV or using computer or video games. These

findings are consistent with the study of Lund HG et al., 2010 who

found that daily hours of television and video game exposure were

not significant predictors of the PSQI score [40]. Also consistent

with Chen et al., 2006 study findings that hours of watching TV/

using computer during weekdays and were not significantly

correlated with adequate sleep [41]. But other studies in Saudi

Arabia, Spain, Norway and USA found that short sleep duration was

associated with more TV watching [16,32,42-44].

In this study, it was found that there was no statistical significant

association between sleep quality and sleeping with lights on. This

finding is consistent with the study of Gellis and Lichstein, 2009

among 220 middle aged adults (mean age 42±12.8 SD) in USA [45].

This study found that there was inverse relation between

daytime napping and sleep quality (p>0.0001). Also using logistic

regression, always daytime napping was significant predictor

of poor sleep quality [OR 4.8, p>0.0001]. This relation could be

attributed to that long and late naps interfere with night sleep. This

finding is consistent with the study of Gellis and Lichstein, 2009

in USA that found significant differences between good and poor

sleepers in relation to daytime napping that poor sleepers were

more likely to nap during the day (PSQI >5) [45]. The same result was obtained by Jefferson et al., 2005 among 516 individuals aged

18 to 65 years in a population based study [46].

In this study, we found association between poor sleep quality

and using bed for activities other than sleep (e.g. reading, watching

TV, mobile phone using or thinking about important matters), the

association was statistically significant (p>0.0001). Several factors

may lead to poor sleep in adolescents who used bed for activities

other than sleep, including that these activities may replace the

time for sleep and it may increase arousal due to the media or

book contents or due to alerting features of the screens including

brightness and the specific wave-length of the screens [35]. This

finding is consistent with the study of Gellis and Lichstein, 2009 in

USA that found that bed activities other than sleep especially more

likely to worry, plan, or think about important matters at bedtime

were greater among poor sleepers (PSQI >5) [45]. In another study

conducted by Lemola et al., 2015 among 362 adolescents aged 12–

17 years in northwestern Switzerland, found that electronic media

use in bed before sleep especially being online (Facebook, Chat

etc.) in bed and having the mobile phone switched on at night was

related to shorter sleep on weekday nights and only being online in

bed before sleep was related with sleep difficulties [35].

The significant association between sleep quality and regularity

of meals pattern (breakfast, lunch and dinner) (p= 0.005, 0.021,

>0.0001 respectively). Adequate sleep time could be attributed

to waking up early and having their breakfast before going to

school. Having regular meals pattern may reflect more stable

family structures with the parents and children having their meals

together, and help adequate sleep [43]. This finding is consistent

with the results of many studies as the study of Cheng et al., 2012

who found that students who skipped breakfast were more likely

to be poor sleepers (PSQI score ≥6) [29]. Also Al Hazzaa et al., 2014

found that having low intake of breakfast decreased the odd of

having adequate sleep duration [43]. On the other hand, irregular

breakfast taking (less than five times per week) [OR 1.6, p=0.012]

and irregular dinner taking (less than five times per week) [OR 1.7,

p=0.006] were significant predictors of poor sleep quality. Also,

Stea et al., 2014 found that having an irregular meal pattern were

associated with short sleep duration [32], the same result was

reported by Chen et al., 2006 that adopting healthy diet (eating

breakfast daily, eating three meals a day, drinking at least 1,500cc

of water daily, choosing foods with little oil, etc.) was negatively

associated with inadequate sleep [41].

Regular carbohydrate eating (once or more per day) and

regular snacks eating (once or more per day) were significant

predictor of poor sleep quality [OR 1.5, p=0.041] and [OR 1.9, CI

p=0.002] respectively. These findings are consistent with the

results of the study of Al-Disi et al., 2010 among 126 Saudi girls

aged 14-18 years, who found that subjects sleeping < five hours/

day showed a significantly higher percent of carbohydrate intake

from their total daily energy intake than those sleeping > seven

hours/day [47]. In other study, among eleven healthy volunteers

aged 34-49 years completed in random order two 14-day stays in

a sleep laboratory with access to palatable food and 5.5-h or 8.5-h

bedtimes. Nedeltcheva et al., 2009 found that sleep restriction was

accompanied by increased consumption of calories from snacks,

with higher carbohydrate content [48]. Proposed mechanisms by

which insufficient sleep may increase caloric consumption from

carbohydrates and snacks include: more time and opportunities for

eating, psychological distress, uninhibited eating (low leptin and

high ghrelin secretion), more energy needed to sustain extended

wakefulness, and changes in appetite hormones [49].

As found in the study results, there were no statistical significant

associations between sleep quality and having milk or its products

or eating vegetables and fruits. This is consistent with the results

of the study of Al-Hazzaa et al., 2014 among Saudi adolescents

who found that the frequency of consumption of vegetables, fruits

and milk/dairy products intake per week were not significantly

associated with sleep duration [43]. Although milk drinking is

thought to promote sleep, this relation was not found in the current

study may be due to the sleep promoting effect limited to drinking

milk at night. This is contradicted with the results of HELENA study

among European adolescents that found that the proportion of

adolescents who eat adequate amounts of fruits and vegetables

was lower in shorter sleepers than in adolescents who slept ≥ eight

hours per day [50]. This difference may be due to different cultural

and social habits of eating behaviors between Arab and European

adolescents.

The current study shows that there was statistical significant

association between drinking caffeinated drinks after 6 pm

and poor sleep quality [OR 1.9, p=0.045]. While there were no

statistical significant association between sleep quality and

regularity of drinking caffeinated drinks per week. These results

may be attributed to short term effect of caffeine on sleep and

those who drink caffeinated drinks early in the day cannot nap

so can have sleep with good quality at night, this is consistent

with Lund et al., 2010 who found that the number of caffeinated

drinks per day did not significantly differ between PSQI groups

[40]. The same result was found by Merdad et al., 2014 that there

was no statistical significant difference of PSQI scores between

different amounts of caffeine intake per day [12]. While Cheng et

al., 2012 found statistical significant association between higher

frequency of tea-drinking (≥3 times / week) and poor sleep quality,

and non-statistical significant association between frequency

of coffee-drinking and sleep quality [29]. While Mindell and his

colleges, in their study among 1473 parents/caregivers of children

ages newborn to 10 years in America, found that regular caffeine

consumption was associated with shorter total sleep time [51]. The

same association was detected by Drescher et al., 2011 among 319

American adolescents between 10-17 years [51].

The results of the current study could be generalized because

different schools from different regions in Assiut city were included.

The current study was limited by being a cross-sectional study;

we could not judge the causal relation between the outcome and

predictors, that the temporal sequence was not clear. to avoid more

elongation of the questionnaire, which could affect the accuracy

of data, the study did not include other factors related to sleep as

academic performance, sleep habits during exam times, weekends,

and holidays. These factors could be studied in other studies.

Conclusion

Poor quality of sleep should be considered a critically important medical problem, especially in adolescents. It’s associated with many life style factors as using illicit drugs, using internet and mobile phones for long time, irregular breakfast and. Dinner time, caffeinated drinks after 6pm and day time napping. A behavioral intervention program should be developed and implemented by the Ministry of Education in secondary schools. Parents should also monitor their sleep timing and behaviors. Mass media should conduct special programs to increase the awareness about sleep needs, healthy sleep patterns, risk factors and consequences of poor sleep to be avoided.

Acknowledgment

Great thanks to the competent research field assistants for helping in data collection.

Disclosure

The authors declare that there was no conflict of interest.

References

- Smaldone A, Honig JC, Byrne MW (2007) Sleepless in America: inadequate sleep and relationships to health and well-being of our nation's children. Pediatrics 119(Supplement 1): S29-S37.

- Sadeh A (2007) Consequences of sleep loss or sleep disruption in children. Sleep medicine clinics 2(3): 513-520.

- Altevogt BM, Colten HR (2006) Sleepdisorders and sleep deprivation: an unmet public health problem: National Academies Press.

- Lucassen EA, Zhao X, Rother KI, Mattingly MS, Courville AB, et al. (2013) Evening chronotype is associated with changes in eating behavior, more sleep apnea, and increased stress hormones in short sleeping obese individuals. PloS one 8(3): e56519.

- Chaput JP, Després JP, Bouchard C, Tremblay A (2007) Short sleep duration is associated with reduced leptin levels and increased adiposity: results from the Quebec family study. Obesity15(1): 253-261.

- Malhotra S, Kushida CA (2013) Primary hypersomnias of central origin. CONTINUUM: Lifelong Learning in Neurology 19(1, Sleep Disorders): 67-85.

- Moo-Estrella J, Pérez-Benítez H, Solís-Rodríguez F, Arankowsky-Sandoval G (2005) Evaluation of depressive symptoms and sleep alterations in college students. Archives of medical research 36(4): 393-398.

- Hounnaklang N, Lertmaharit S, Lohsoonthorn V, Rattananupong T (2016) Prevalence of poor sleep quality and its correlates among high school students in Bangkok, Thailand. Journal of Health Research 30(2): 91-98.

- Chung K-F, Cheung M-M (2008) Sleep-wake patterns and sleep disturbance among Hong Kong Chinese adolescents. Sleep 31(2): 185-194.

- Hirshkowitz M, Whiton K, Albert SM, Alessi C, Bruni O, et al. (2015) National Sleep Foundation’s updated sleep duration recommendations. Sleep Health 1(4): 233-243.

- Kesintha A, Rampal L, Sherina M, Kalaiselvam T (2018) Prevalence and predictors of poor sleep quality among secondary school students in Gombak District, Selangor. The Medical journal of Malaysia; 73(1): 31-40.

- Merdad RA, Merdad LA, Nassif RA, El-Derwi D, Wali SO (2014) Sleep habits in adolescents of Saudi Arabia; distinct patterns and extreme sleep schedules. Sleep medicine 15(11): 1370-1378.

- Al-Hazzaa HM, Musaiger AO, Abahussain NA, Al-Sobayel HI, Qahwaji DM (2012) Prevalence of short sleep duration and its association with obesity among adolescents 15-to 19-year olds: A cross-sectional study from three major cities in Saudi Arabia. Annals of thoracic medicine 7(3): 133-139.

- Calamaro CJ, Mason TB, Ratcliffe SJ (2009) Adolescents living the 24/7 lifestyle: effects of caffeine and technology on sleep duration and daytime functioning. Pediatrics 123(6): e1005-e10.

- Chokroverty S (2009) Sleep Disorders Medicine E-Book: Basic Science, Technical Considerations, and Clinical Aspects: Elsevier Health Sciences.

- McKnight-Eily LR, Eaton DK, Lowry R, Croft JB, Presley-Cantrell L, et al. (2011) Relationships between hours of sleep and health-risk behaviors in US adolescent students. Preventive medicine 53(4-5): 271-273.

- Van den Bulck J (2003) Text messaging as a cause of sleep interruption in adolescents, evidence from a cross‐sectional study. Journal of Sleep Researc 12(3): 263.

- Van den Bulck J (2004) Television viewing, computer game playing, and Internet use and self-reported time to bed and time out of bed in secondary-school children. Sleep 27(1): 101-104.

- Zhou HQ, Shi WB, Wang XF, Yao M, Cheng GY, et al. (2012) An epidemiological study of sleep quality in adolescents in South China: a school‐based study. Child: care, health and development 38(4): 581-587.

- Ismail DM, Mahran DG, Zarzour AH, Sheahata GA (2017) Sleep quality and its health correlates among Egyptian secondary school students. Journal of Social, Behavioral, and Health Sciences 11(1):5.2

- Buysse DJ, Reynolds III CF, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ (1989) The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry research 28(2): 193-213.

- Suleiman KH, Yates BC, Berger AM, Pozehl B, Meza J (2010) Translating the Pittsburgh sleep quality index into Arabic. Western Journal of Nursing Research 32(2): 250-68.

- Gradisar M, Gardner G, Dohnt H (2011) Recent worldwide sleep patterns and problems during adolescence: a review and meta-analysis of age, region, and sleep. Sleep medicine 12(2):110-8.

- Dijk DJ, Duffy JF, Czeisler CA (2000) Contribution of circadian physiology and sleep homeostasis to age-related changes in human sleep. Chronobiology international 17(3): 285-311.

- Voderholzer U, Al‐Shajlawi A, Weske G, Feige B, Riemann D (2003) Are there gender differences in objective and subjective sleep measures? A study of insomniacs and healthy controls. Depression and anxiety 17(3): 162-72.

- Munezawa T, Kaneita Y, Osaki Y, Kanda H, Minowa M, et al. (2011) The association between use of mobile phones after lights out and sleep disturbances among Japanese adolescents: a nationwide cross-sectional survey. Sleep 34(8): 1013-1020.

- Liu X, Zhao Z, Jia C, Buysse DJ (2008) Sleep patterns and problems among Chinese adolescents. Pediatrics 121(6): 1165-1173.

- Haseli-Mashhadi N, Dadd T, Pan A, Yu Z, Lin X, et al. (2009) Sleep quality in middle-aged and elderly Chinese: distribution, associated factors and associations with cardio-metabolic risk factors. BMC Public Health 9(1): 130.

- Cheng SH, Shih C-C, Lee IH, Hou Y-W, Chen KC, et al. (2012) A study on the sleep quality of incoming university students. Psychiatry research 197(3): 270-274.

- Bidulescu A, Din-Dzietham R, Coverson DL, Chen Z, Meng Y-X, et al. (2010) Interaction of sleep quality and psychosocial stress on obesity in African Americans: the Cardiovascular Health Epidemiology Study (CHES). BMC Public Health 10(1): 581.

- Hung HC, Yang YC, Ou HY, Wu JS, Lu FH, et al. (2013) The association between self‐reported sleep quality and overweight in a Chinese population. Obesity 21(3): 486-492.

- Stea T, Knutsen T, Torstveit M (2014) Association between short time in bed, health-risk behaviors and poor academic achievement among Norwegian adolescents. Sleep medicin 15(6): 666-671.

- Ohida T, Osaki Y, Doi Y, Tanihata T, Minowa M, et al. (2004) An epidemiologic study of self-reported sleep problems among Japanese adolescents. Sleep 27(5): 978-985.

- Jaehne A, Unbehaun T, Feige B, Lutz UC, Batra A, et al. (2012) How smoking affects sleep: a polysomnographical analysis. Sleep medicine 13(10): 1286-1292.

- Lemola S, Perkinson-Gloor N, Brand S, Dewald-Kaufmann JF, Grob A (2015) Adolescents’ electronic media use at night, sleep disturbance, and depressive symptoms in the smartphone age. Journal of youth and adolescence 44(2): 405-418.

- Canan F, Yildirim O, Sinani G, Ozturk O, Ustunel TY, et al. (2013) Internet addiction and sleep disturbance symptoms among Turkish high school students. Sleep and Biological Rhythms 11(3): 210-213.

- Arora T, Broglia E, Thomas GN, Taheri S (2014) Associations between specific technologies and adolescent sleep quantity, sleep quality, and parasomnias. Sleep medicine 15(2): 240-247.

- Yang YS, Yen JY, Ko CH, Cheng CP, Yen CF (2010) The association between problematic cellular phone use and risky behaviors and low self-esteem among Taiwanese adolescents. BMC Public Health 10(1): 217.

- White AG, Buboltz W, Igou F (2011) Mobile phone use and sleep quality and length in college students. International Journal of Humanities and Social Science 1(18): 51-58.

- Lund HG, Reider BD, Whiting AB, Prichard JR (2010) Sleep patterns and predictors of disturbed sleep in a large population of college students. Journal of adolescent health 46(2): 124-132.

- Chen MY, Wang EK, Jeng YJ (2006) Adequate sleep among adolescents is positively associated with health status and health-related behaviors. BMC Public Health 6(1): 59.

- Ortega FB, Chillón P, Ruiz JR, Delgado M, Albers U, et al. (2010) Sleep patterns in Spanish adolescents: associations with TV watching and leisure-time physical activity. European journal of applied physiology 110(3): 563-573.

- Al‐Hazzaa H, Musaiger A, Abahussain N, Al‐Sobayel H, Qahwaji D (2014) Lifestyle correlates of self‐reported sleep duration among Saudi adolescents: a multicentre school‐based cross‐sectional study. Child: care, health and development 40(4): 533-542.

- Foti KE, Eaton DK, Lowry R, McKnight-Ely LR (2011) Sufficient sleep, physical activity, and sedentary behaviors. American journal of preventive medicine 41(6): 596-602.

- Gellis LA, Lichstein KL (2009) Sleep hygiene practices of good and poor sleepers in the United States: an internet-based study. Behavior Therapy 40(1): 1-9.

- Jefferson CD, Drake CL, Scofield HM, Myers E, McClure T, et al. (2005) Sleep hygiene practices in a population-based sample of insomniacs. Sleep 28(5): 611-615.

- Al-Disi D, Al-Daghri N, Khanam L, Al-Othman A, Al-Saif M, et al. (2010) Subjective sleep duration and quality influence diet composition and circulating adipocytokines and ghrelin levels in teen-age girls. Endocrine journal 57(10): 915-923.

- Nedeltcheva AV, Kilkus JM, Imperial J, Kasza K, Schoeller DA, et al. (2008) Sleep curtailment is accompanied by increased intake of calories from snacks–. The American journal of clinical nutrition; 89(1): 126-33.

- Chaput JP (2014) Sleep patterns, diet quality and energy balance. Physiology & behavior 134: 86-91.

- Garaulet M, Ortega F, Ruiz J, Rey-Lopez J, Beghin L, et al. (2011) Short sleep duration is associated with increased obesity markers in European adolescents: effect of physical activity and dietary habits. The HELENA study. International journal of obesity 35(10): 1308-1317.

- Mindell JA, Meltzer LJ, Carskadon MA, Chervin RD (2009) Developmental aspects of sleep hygiene: findings from the 2004 National Sleep Foundation Sleep in America Poll. Sleep medicine 10(7): 771-779.

- Drescher AA, Goodwin JL, Silva GE, Quan SF (2011) Caffeine and screen time in adolescence: associations with short sleep and obesity. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine 7(04): 337-342.

-

Vladimir A Mikhaylov. Intravenous Laser Therapy in the Complex Treatment of Nervous System and Brain Diseases and the New Development Mechanism of the Diseases. Arch Neurol & Neurosci. 11(4): 2021. ANN.MS.ID.000768.

-

Sleep quality; Lifestyle correlates; Secondary schools, napping, cognitive restitution, learning, decision making, memory consolidation, weight gain, obesity, daytime sleepiness, exhaustion, impaired glucose tolerance and diabetes, depression and anxiety, impaired memory, and higher risk of motor vehicle accidents.

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.