Short Communication

Short Communication

Rest-Activity Circadian Rhythm and Light Exposure Using Wrist Actigraphy in ICU Patients

Αnna Korompeli1*, Nadia Kavrochorianou2 and Pavlos Myrianthefs3

1Clinical and Laboratory Teaching Staff, Greece

3Professor of Critical Care and Pulmonary Medicine, Greece

1,2,3National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, School of Health Sciences, Faculty of Nursing, Greece

Anna Korompeli, RN, MSc, PhD, Clinical and Laboratory Teaching Staff, 12 Notou str, 15342, Ag. Paraskevi, Athens, Greece.

Received Date: March 23, 2022; Published Date: April 08, 2022

Introduction

Actigraphy (ACTG) is easy to use and has proved reliable in non-critical populations of patients. It has been used to track circadian rest-activity cycles and to identify states of wakefulness and sleep [1]. A more recent study has found that ACTG have a moderate level of agreement with PSG in distinguishing between sleep and wakeful states which is more profound in non-ventilated patients [2]. Moreover, ACTG provides an objective physiological assessment via non-invasive use of motion accelerometers to detect multiplanar gross motor activity [2], indicating purposeful or nonpurposeful movement of patients. Especially, non parametric values (IS: intradaily stability; IV: interdaily variability; L5: least active 5-hour period; M10: most active 10-hour period; and RA: relative amplitude) can quantify circadian rest- activity rhythm providing an indication of circadian rhythmicity. The non-parametric approaches measured in order to investigate 24 hour rest-activity circadian patterns are: M-10 which is the average activity level (counts) of the 10 most active hours indicating patients’ daily activity. Moreover, L-5 is the average activity level (counts) of the least active 5-h period, reflecting patients’ nocturnal activity [3]. The relative amplitude (RA) of the rhythm, is the difference between M-10 and L-5 in the average 24-h pattern, normalized by their sum, ranging between >0 and <14. Higher RAs indicate a more robust 24 hour rest-activity rhythm, reflecting both relatively lower activity during the night and higher activity when awake [2]. Finally, IS provides an estimate of how closely the 24 hour rest-activity rhythm follows the 24 hour light-dark cycle (range: >0 and <1). Higher IS indicates good synchronization to light and other environmental cues that regulate circadian rhythms [3,4,5].

Furthermore, ICU lighting is not typically controlled to cycle with bright light levels during the daytime and darkness at night, as the focus is on medical and nursing care and interventions. Research findings suggest that cycled lighting have positive effects on patient length of stay in the ICU recovery and well-being [6].

Aim

The aim of the study was to estimate the status of restactivity circadian rhythm and light exposure (lux) using wrist actigraphy in ICU patients before their discharge. Particularly, we examined actigraphy data including light exposure (lux) and four nonparametric variables of actigraphy: M10, L5, RA, IS.

Method

We investigated recently extubated non mechanically ventilated ICU patients eligible for early mobility interventions planned to be discharged the day after the end of the actigraphy measurement. One actigraphy was placed on the patients’ nondominant wrist. To ensure a high degree of homogeneity, patients were enrolled according to the following inclusion criteria, which had to be met at least 48h prior to study entry and maintained throughout the whole 24–72 h of the study period: 18–87 years of age, afebrile (Body Temperature <38.3°C), cessation of analog sedation and mechanical ventilation and/or other disturbance necessitating analog sedation [5].

This observational study was conducted in a small, single-ward University ICU at a Greek general hospital in Athens, as refereed to a previous study [7]. Generally, total admissions to this ICU are low because the study site is a training hospital without a highdependency unit (HDU), with HDU patients instead assigned to the ICU, resulting in a long mean length of stay. The windows in the ICU offered access to natural lighting. Artificial lighting, consisting of overhead panels containing bright white fluorescent lights, illuminated the ICU. The arrangement of beds in the ICU led to a distinction between an array of three fully equipped beds close to the windows on the ‘light’ side and six otherwise identical beds bounded by a corridor on the ‘dark’ side in the same large room. Patients were assigned to a bed on either side of the ICU depending on bed availability. Although not random, the assignment was not based on patients’ clinical condition. The same nursing staff attended both sets of patients. Notably, this study did not manipulate light exposure but took advantage of natural fluctuations of light within the existing ICU design.

‘Daytime’ was set from 8 a.m. to 8 p.m., and ‘nighttime’ was set from 8 p.m. to 8 a.m. Light exposure (lux) and rest–activity rhythm of the patients were monitored for 24–72 consecutive hours and analysed separately for daytime and nighttime using the MotionWatch 8© actigraphy system (MW8, CamNtech, Cambridge, UK). Activity and light data were recorded with a 1-minute epoch and tracked with MotionWare 1.1.20 software (CamNtech, Cambridge, UK). Data were recorded with a one-minute epoch, tracked with MotionWare 1.1.20 software and analysed using the MotionWatch 8© actigraphy system (MW8, CamNtech, Cambridge, UK).

Ethical and Research Approvals

The study was conducted in full accordance with ethical principles of the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki (version, 2002), and was independently reviewed and approved by the ethical committee of the hospital. Informed consent forms were signed by all patients, or when patients were unable to sign, consent was obtained from their legal representatives

Results

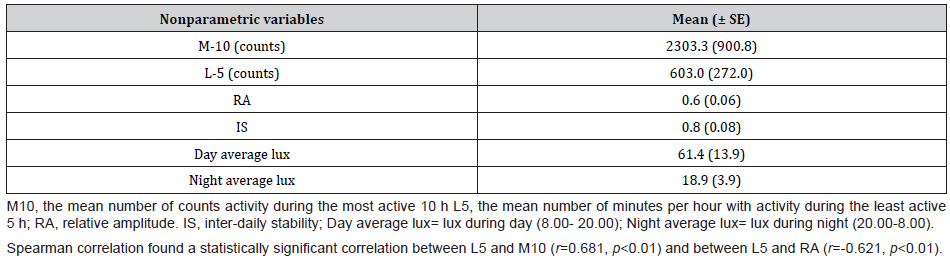

We included 13 ICU survivors (6 males) of mean age 65.9 ± 4.3 years admitted for medical (7 patients) reasons or for postoperative care (6 patients). Mean APACHE II and SOFA score were 19.5 ± 2.9 and 7.4 ± 0.7 respectively. Mean length of stay (LOS) was 23.6 ± =7.1 days. Mean actigraphy use was 46.2 ± 6.9 hours. Non parametric variables and light exposure determined by actigraphy are presented below (Table 1).

Table 1:Reported nonparametric variables and light exposure determined by actigraphy.

Discussion

We found that ACTG maybe useful to record and distinguish the rest-activity circadian rhythms in ICU patients. According to our preliminary data, our ICU light exposure (lux) during daytime and nighttime are within the normal range [7]. Also, M-10 and L-5 measurements in our population are higher, RA is lower and IS, is higher compared to healthy population [3,4]. M-10 and L-5 are higher indicating that our patients are more active during their 10 more active hours and more active during their 5 less active hours meaning a possible hyperkinetic state and a gross motor activity before ICU discharge. Our patients’ RA was 0.6, meaning that the 24 hour patients’ rest-activity rhythm is not really robust, reflecting both relatively higher activity during the night and lower activity when awake a possible indicator of loss of day-night orientation. On the other hand, IS was 0.8, indicating ‘’good’’ synchronization to light and other environmental cues. However, RA is suggested to be a better indicator of the strength of rest–activity patterns than IS [4].

To our knowledge, non-parametric variables of actigraphy have not been extensively investigated in ICU patients [8,9]. Our data suggest that actigraphy in addition to the investigation of sleep patterns may be useful to determine light exposure (lux) and in investigating light effect on patients’ daytime and nighttime activity [8,9]. ICU interventions based on rest activity pattern of patients may play a role in reducing physical and neuropsychological impairments in ICU survivors in both the short- and long-term, highlighting the importance of studying this population. More data are required to investigate patients’ activity as determined by wrist actigraphy in an ICU environment. It would be of great interest to plan interventions to improve 24 hour rest-activity circadian rhythm, like bed position oriented to light during the hours of the day with light, and improved communication techniques between nursing personnel and patients, providing better regulation of restactivity circadian rhythms.

Conclusion

Light intensity appears to have implications for circadian rest-activity pattern. This study points towards a need to better stimulate daily variability of light in the ICU settings regarding synchronization of ICU survivor patients with environmental cues. Measuring the circadian rest-activity pattern of ICU survivors before discharge it could be predictive for the evolution of their health level.

Limitations

The results of this study need to be considered in the context of several limitations. Clearly, the sample size was small. ICU survivor patients are clearly an unusual subject pool for circadian studies. They were partly chosen for this study to ensure that the differences in their responses as patients could be, to a significant degree, attributed to differences in bed positioning regarding light exposure.

Acknowledgement

None

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest.

References

- Grap MJ, Borchers CT, Munro CL, Elswick RK, Sessler CN (2005) Actigraphy in the critically ill: correlation with activity, agitation, and sedation. Am J Crit Care 14(1): 52-60.

- Delaney LJ, Litton E, Melehan KL, Huang HC, Lopez V, et al. (2021) The feasibility and reliability of actigraphy to monitor sleep in intensive care patients: an observational study. Crit Care 25(1): 42.

- Ferreira ABD, Schaedler T, Mendes JV, Anacleto TS, Louzada FM (2019) Circadian ontogeny through the lens of nonparametric variables of actigraphy. Chronobiol Int 36(9): 1184-1189.

- Mitchell JA, Quante M, Godbole S, James P, Hipp JA, et al. (2017) Variation in actigraphy-estimated rest-activity patterns by demographic factors. Chronobiol Int 34(8):1042-1056.

- Rensen N, Steur LMH, Wijnen N, Someren EJW Van, Kaspers GJL, et al. (2020) Actigraphic estimates of sleep and the sleep-wake rhythm, and 6-sulfatoxymelatonin levels in healthy Dutch children. Chronobiol Int 37(5): 660-672.

- Ritchie HK, Stothard ER, Wright KP (2015) Entrainment of the Human Circadian Clock to the Light-Dark Cycle and its Impact on Patients in the ICU and Nursing Home Settings. Curr Pharm Des 21(24): 3438-342.

- Korompeli A, Kavrochorianou N, Molcan L, Muurlink O, Boutzouka E, et al. (2019) Light affects heart rate's 24‐h rhythmicity in intensive care unit patients: an observational study. Nurs Crit Care 24: 320-325.

- Vinzio S, Ruellan A, Perrin AE, Schlienger JL, Goichot B (2003) Actigraphic assessment of the circadian rest–activity rhythm in elderly patients hospitalized in an acute care unit. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 57: 53-58.

- Mistraletti G, Taverna M, Sabbatini G, Carloni E, Bolgiaghi L, et al. (2009) Actigraphic monitoring in critically ill patients: preliminary results toward an "observation-guided sedation. J Crit Care 24(4): 563-567.

-

Αnna Korompeli, Nadia Kavrochorianou, Pavlos Myrianthefs. Rest-Activity Circadian Rhythm and Light Exposure Using Wrist Actigraphy in ICU Patients. Arch Neurol & Neurosci. 12(3): 2022. ANN.MS.ID.000787. DOI: 10.33552/ANN.2022.12.000787

-

: Wrist Actigraphy, Circadian Rhythmicity, Nonparametric, Homogeneity, ICU Survivor, Circadian Rhythms, Neuropsychological Impairments, Synchronization, Environmental.

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.