Case Report

Case Report

Psychomotor Retardation, Brain Calcifications and West’s Syndrome in an Infant

Kombate D1*, Diatewa JE2, Agbotsou K2, Apetse K2, Assogba K2, Bélo M2 and Balogou AAK2

1Department of Neurology, University of Kara, Togo

2Department of Neurology, University of Lomé, Togo

Kombate D, University of Kara, Pobox: 404 Kara, Togo.

Received Date: June 18, 2020; Published Date: July 02, 2020

Abstract

Introduction: West’s syndrome is a severe epileptic syndrome. It may be secondary to brain damage or of unknown aetiology. We report one case of West’s syndrome in an infant and underlined the difficulties in aetiological research with poor technical platform.

Observation: A 2-year-4-month-old infant was admitted in neurology on September 7, 2012 for spasms seizures and chewing for one year. At 1 year of age, the infant had had several episodes of convulsions in the context of fever. He had no particular neonatal history, he was born at term. He is the second child of a sibling of two children. At the physical examination there was no staturo-ponderal delay but a psychomotor delay. Standing and walking were impossible. There was axial hypotonia. Oral language was mutic with a few poorly articulated syllables. Eye movement and swallowing were normal. Sphincter control did not exist. Brain CT scan showed multiple calcifications involving the gray nuclei and brain atrophy. Anti-epileptic treatment with vigabatrin and corticosteroid therapy in addition to functional rehabilitation did not improve the outcome.

Discussion: West syndrome has several aetiologies. Psychomotor retardation is always present in this syndrome. It is described as the infantile spasms that occur in infants under 1 year of age. There are two major groups in this syndrome, namely the structural forms, which are the consequences of severe antenatal or perinatal brain damage, and the forms of unknown aetiology. The structural forms are the most pejorative; they are marked by psychomotor development delay and the existence of a brain lesion that precedes the onset of the disease. The electroencephalographic (EEG) displayed a disorganization recording with irregular slow waves. This pattern is described as hypsarhythmic.

Conclusion: The management of West syndrome is difficult. The prognosis remains severe especially in the structural form.

Keywords: West’s syndrome; Cerebral calcifications; Hypsarhythmia

Introduction

West’s syndrome is a severe epileptic syndrome. It occurs in infants under one year old. It may be symptomatic or of unknown aetiology. Today classified among the epileptic syndromes of the infant [1], West’s syndrome has a bad outcome for epileptic seizures as well as for the psychomotor development of the victims. Even in its structural form, aetiological diagnosis remains difficult, especially in a context of poor technical plateform [2].

Objective

We report one case of West’s syndrome in an infant and underlined the difficulties in etiological research.

Observation

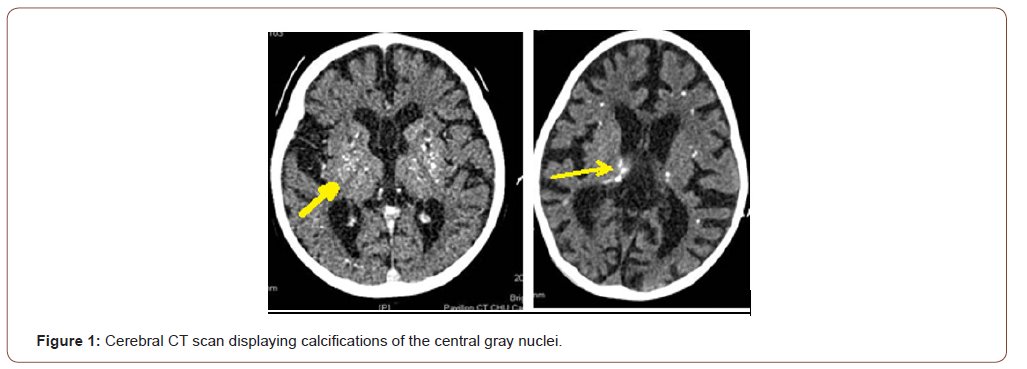

A 2-year, 4-month-old male infant was admitted in neurology on September 7, 2012 for generalized seizures with spasm in flexion and chewing for one year. Psychomotor development was normal up to 1 year of age, at which time the infant would have had several episodes of convulsions in the context of fever, treated with aspirin and valproic acid. A regression of psychomotor acquisitions occurred in a context of repeated spasm. He had no particular neonatal history; he was born at term. He is the second child of a sibling group of two children. His 4-year-old brother was doing well. The examination noticed: a weight of 16 kg, the height was 90 cm. Consciousness was normal on the paediatric Glasgow scale. There was no staturo-ponderal delay but a severe psychomotor retardation on the Bayley III scale [3] with a psychomotor age corresponding to 4 months. Execution of the instructions was impossible. Oral language was mutic with a few poorly articulated syllables. Standing and walking were impossible. There was no autonomy in the sitting position. There was an axial and neck hypotonia with a motor deficit of the four limbs at 3/5 on the muscle testing scale. There was no obvious sensory deficit. The osteotendinous and plantar skin reflexes were weak in the four limbs with a bilateral Babinski sign. Ocular motricity, eye fundus exam and swallowing were normal. The sphincter control did not exist (urinary and anal). The cerebral computed tomography (CT) scan had shown multiple calcifications predominating in the central gray nuclei and significant brain atrophy (Figure 1).

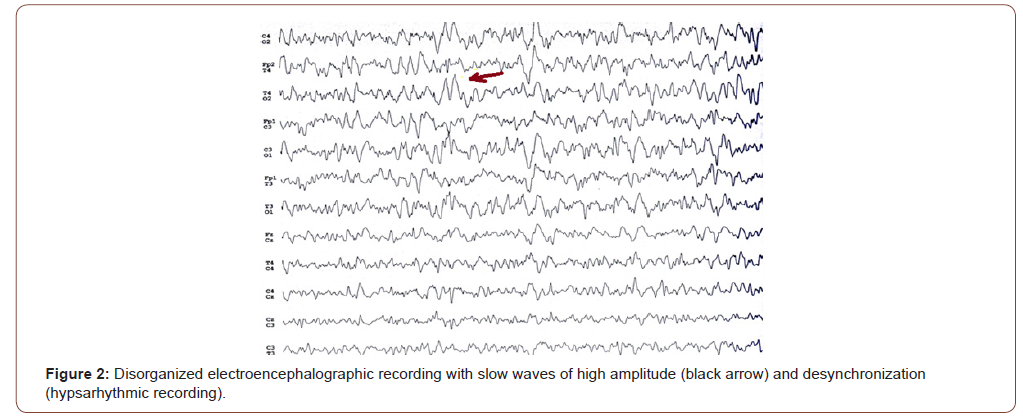

The EEG recording was disorganized with no baseline rhythm, with hight amplitude slow waves and desynchronization (Figure 2). This pattern was characteristic of West’s syndrome, described as a hypsarhythmic pattern. The biologic test displayed a normal blood formula count (Hemoglobin 14g/dl), sedimentation rate 20mm in the first hour, transaminases and gammaglutamyl transferases, blood glucose, creatinine and cerebrospinal fluid were normal. Toxoplasmic serology (Immunoglobulin Gamma and Mu) was negative. Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) and cytomegalovirus (CMV) serology was negative. Thyroid stimulating hormone was normal. However, the diagnosis of Cytomegalovirus infection was based on the appearance of cerebral calcifications. She was treated with intravenous adrenocorticotrophic hormone (ACTH) at 1.6mg/day and then with vigabatrin at 1500 milligrams twice daily, combined with functional readaptation. However, the effectiveness of the treatment after two years was not remarkable The spasms persisted as well as the psychomotor retardation.

Discussion

West’s syndrome is a severe epileptic syndrome. Psychomotor retardation is always present in this syndrome. These are infantile spasms that occur in infants before 1 year. There are two major groups in this syndrome including structural forms, which are the consequences of severe antenatal or perinatal brain damage. The second form is of unknown aetiology [2]. Our case report was a structural form, due to encephalitis. The structural forms are the most pejorative; they are marked by psychomotor development delay and cerebral lesion that precedes the onset of the disease. A wide range of aetiologies can be associated [4]. Infantile spasms in flexion or extension are associated with psychomotor development delay and regression of acquisitions. This was typically a flexion spasm in this child with a significant delay in psychomotor development. Our patient did not have staturo-ponderal retardation. In the structural forms, the clinic and EEG findings suggest the existence of a brain lesion. West syndrome of unknown aetiologies should have a better outcome [5]. The pathophysiology is poorly understood. Infantile spasm is thought to be the consequence of a desynchronization of the temporal lobe with two or more developmental processes of the central nervous system and a specific disturbance of brain function [6]. Treatment is based on corticosteroids and vigabatrin, but also on valproic acid, prednisolone and tetracosactide [7]. The EEG pattern is disorganized with slow waves of high amplitude associated with low amplitude waves. This EEG is hypsarhythmic. The spasms are in bursts of 10 to 20 spasms, over a period of 10 to 20 minutes, frequently occurring in wakefulness fluctuation. The spasms are associated with high amplitudes slow waves followed by depression. The treatment is most often disappointing for epileptic seizures and the psychomotor retardation does not improve. This case report highlights the difficulties of aetiological diagnosis of cerebral calcifications especially in a context of poor technical platform. The brain CT scan remains important to diagnose the cerebral calcifications and the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is very useful to find the germ. Several diseases can lead to cerebral calcifications such as CMV infection and zika virus infection, parasitic diseases such as cerebral toxoplasmosis, cysticercosis, embryofoetopathies, hyperparathyroidism, perinatal anoxia and genetic diseases such as Aicari syndrome [8].

Conclusion

The diagnosis of West’s syndrome is relatively easy with the presence of spasms and a hypsarhythmic EEG recording. But the aetiological research is most often difficult. The management is difficult with a pejorative outcome. It is imperative to prevent maternal-foetal and neonatal infections in order to reduce the occurrence of this syndrome. In some cases even if the aetiology is known, the consequences of the infection may be irreversible.

Acknowledgement

None.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest.

References

- Robert S Fisher, J Helen Cross, Jacqueline A French, Norimichi Higurashi, Edouard Hirsch, et al. (2017) Operational classification of seizure types by the International League Against Epilepsy: Position Paper of the ILAE Commission for Classification and Terminology. Epilepsia 58(4): 522-530.

- Gulati S, Jain P, Kannan L, Sehgal R, Chakrabarty B (2015) The Clinical Characteristics and Treatment Response in Children with West Syndrome in a Developing Country: A Retrospective Case Record Analysis. J Child Neurol 30(11): 1440-1447.

- Jackson BJ, Needelman H, Roberts H, Willet S, McMorris C (2012) Bayley Scales of Infant Development Screening Test-Gross Motor Subtest: efficacy in determining need for services. Pediatr Phys Ther 24(1): 58-62.

- Lux AL, Osborne JP (2011) A proposal for case definitions and outcome measures in studies of infantile spasms and west syndrome: consensus statement of the west Delphi group. Epilepsia 45: 1416-1428.

- Paciorkowski AR, Thio LL, Dobyns WB (2011) Genetic and biologic classification of infantile spasms. Pediatr Neurol 45: 355-367.

- Osborne JP, Lux AL, Edwards SW, Hancock E, Johnson AL, et al. (2010) The underlying etiology of infantile spasms (West syndrome): information from the United Kingdom Infantile Spasms Study (UKISS) on contemporary causes and their classification. Epilepsia 51: 2168-2174.

- Frost JD, Hrachovy RA (2005) Pathogenesis of infantile spasms: a model based on developpemental desynchronisation. J Clin Neurophysiol 1: 25-36.

- Stafstrom CE, Arnason BG, Baram TZ, Catania A, Cortez MA, et al. (2011) Treatment of infantile spasms: emerging insights from clinical and basic science perspectives. J Child Neurol 26: 1411-1421.

-

Kombate D, Diatewa JE, Agbotsou K, Apetse K. Psychomotor Retardation, Brain Calcifications and West’s Syndrome in an Infant. Arch Neurol & Neurosci. 8(2): 2020. ANN.MS.ID.000681.

-

Psychomotor, Brain, Syndrome, Aetiology, Cerebral calcifications, Hypsarhythmia

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.