Research Article

Research Article

Patients with Dementia Assessing their Quality of Life

Aikaterini Frantzana, MSc, RN Operating Theatre Nurse, George Papanikolaou Hospital, Thessaloniki, Greece, European University of Cyprus, Nicosia, Cyprus.

Received Date: January 26,2020; Published Date: January 31, 2020

Abstract

Introduction: The term “Dementia” does not refer to a single disease, but to a set of chronic diseases that are the result of the atrophy of the Central Nervous System. Brain neurons are constantly degenerating, resulting in large areas of atrophic cerebral cortex; in the final stage, the brain may often weigh less than 1000g.

Purpose: The purpose of this review study is to investigate the quality of life characteristics of dementia patients, and trace ways how it may be improved.

Material and methods: The study material consisted of articles on the topic found in Greek and international databases such as: Google Scholar, Mednet, PubMed, Medline and the Hellenic Academic Libraries Association (HEAL-Link), using the keywords: quality of life, dementia and dementia patients. The exclusion criterion for the articles was the language, except for Greek and English. Mostly, only articles and studies accessible to authors were used.

Results: Dementia is known to have many organic symptoms and complications that health professionals are called upon to deal with and even prevent, thereby promoting the quality of life of these patients. The healing process should also be addressed to the caregivers. Nurses should be encouraged to educate caregivers and patients about the diagnosis, prognosis, pharmaceutical and non-pharmaceutical strategies that are likely to prove very useful, recognizing that caregivers have an important role to play in managing their problems.

Conclusion: Dementia is a major medical and social problem nowadays, and therefore, the planning of state actions should focus on prevention and management, with the support and expansion of support agencies. Advances in life sciences increase the likelihood of understanding the complex risk factors as regards dementia and suggest appropriate therapeutic interventions.

Introduction

In Greek, the term “dementia” equals to the word “anoia” which includes an alpha privative and the word mind [1]. According to Alzheimer Atlas of Disease: ‘‘Dementia is the term that describes the loss of cognitive abilities in a variety of areas of cognitive functioning, such as memory, reason, executive functions and visual-auditory skills. It is so severe that it interferes with one’s daily, professional and social activities’’ [2]. The term does not refer to a single disease, but to a set of chronic diseases that are the result of the atrophy of the Central Nervous System. Brain neurons are constantly degenerating, resulting in large areas of atrophic cerebral cortex; in the final stage, the brain may often weigh less than 1000g [3].

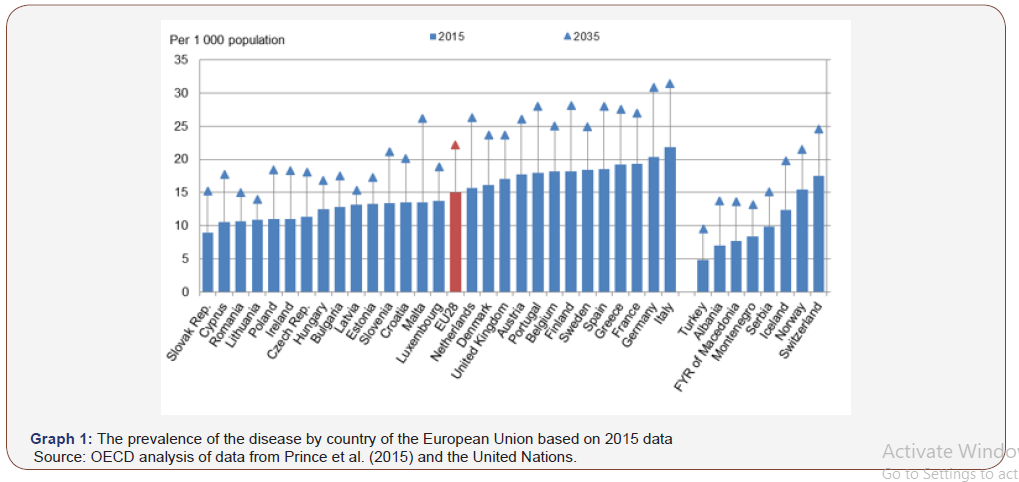

WHO estimated the global number of dementia patients in 2015 to be 47.5 million people, while projective studies raise that figure to 75.6 million patients by 2030 and 135 million by 2050 (WHO 2015) The global financial cost was estimated at $604 billion in 2010 with the prospect of an increase in life expectancy [4]. The number of patients with dementia was estimated at 9.5 million in 2015 at EU level; this number corresponds to one dementia patient in 50 healthy EU residents. However, the prevalence of the disease is not uniformly distributed across the different European countries. Graph 1 below shows the prevalence of the disease by country of the European Union based on 2015 data. (OECD, 2015) (Graph 1), Source: OECD analysis of data from Prince et al. (2015) and the United Nations (Graph 1).

HELIAD (Hellenic Longitudinal Investigation of Aging and Diet) study showed that the incidence of dementia in Greece is estimated at 4.6% for people over 65. It is a relatively lower rate than other

European populations rising to 6%. Additionally, the incidence of mild mental disorder is 11.8% in persons over 65 years of age [5]. In the last two decades, there has also been a strong interest in the issue of quality of life. Quality of life characterizes various aspects of a person’s life, such as home, work, environment, transportation, entertainment, health or even the products we consume [6]. Studies have shown that better health care (physical and mental) was more associated with higher quality of life. This finding is important in view of the fact that health is a potentially modifiable factor and can be of practical use in the need to label the health monitoring of patients with dementia [7]. The purpose of this review study is to investigate the quality of life characteristics of dementia patients, and trace ways how it may be improved.

Methodology

The study material consisted of articles on the topic found in Greek and international databases such as: Google Scholar, Mednet, Pubmed, Medline and the Hellenic Academic Libraries Association (HEAL-Link), using the keywords: quality of life, dementia and dementia patients. The exclusion criterion for the articles was the language, except for Greek and English. Mostly, only articles and studies accessible to authors were used.

Discussing Dementia

Dementia is a mental disorder that generally comes from organic or metabolic disorders affecting the brain. The dementia syndrome is usually progressive or chronic and there is a disorder of many upper cortical functions. These functions include memory, thinking, orientation, comprehension, performing arithmetic, learning ability, language and judgment [8]. Dementia could be the product of many different illnesses while impairments in mental ability can be reversible or irreversible depending on its reason. The most common forms of dementia are the following:

Alzheimer’s disease

Alzheimer’s disease

Alzheimer’s disease is a neurodegenerative disorder that results in the gradual disruption of one’s cognitive and functional abilities leading to social isolation and loss of social roles [9]). It is the most common form of dementia, as it accounts for over 50-70% of cases after the age of 65 [10].

The American Psychiatric Society based on the DSM-IV-TR Diagnostic Tool uses the following criteria to diagnose the disease [11]:

1) A Documentation of dementia through reliable scales (e.g. Mini Mental Test, Blessed Roth Dementia Scale) with concomitant neuropsychological evaluation.

2) There is at least one disorder of cognitive function, the socalled four A’s of the disease, which is translated into cognitive impairment related to cognition (ignorance), reason (aphasia), mobility (inactivity) and memory (amnesia).

3) Gradual memory decline.

4) Absence of changes in consciousness.

5) The onset of the disease occurs between the ages of 40 and 90 years of human life.

6) Absence of other diseases of the Central Nervous System, such as metabolic diseases (e.g. vitamin B12 deficiency, hypothyroidism), autoimmune diseases (e.g. lupus erythematosus) and diseases due to the use of toxic substances or HIV infection.

Vascular dementia

Vascular dementia accounts for 10-20% of cases of dementia and it is the second most frequent type of dementia. More often than not, it is due to strokes or diseases affecting arteries (e.g. diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, etc.). According to the ICD-10 classification, vascular dementia is the result of cerebral infarctions, which lead to progressive necrosis of the brain [12]. The onset of vascular dementia is sudden and is characterized by abrupt changes in function. The deterioration of the disease is gradual, while the treatment of hypertension and vascular disease may slow its progression [13].

Lewy body dementia

Lewy body dementia is estimated to be the second or third most common form of dementia affecting people over 65 after Alzheimer’s disease. Lewy bodies are located in the cerebral cortex. Amongst clinical findings are the presence of dementia and evidence of Parkinsonism. There is tremor, stiffness, flexion of the torso and extremities. Optical hallucinations are present, and patients may have a picture of varying confused states. Psychosis is also a common phenomenon [14].

Frontotemporal dementia and pick’s disease

Frontotemporal dementia is the fourth most common form of dementia, accounting for 5-10% of all cases. This type of dementia (including Pick’s disease) affects the anterior (frontal lobe) and lateral (temporal lobe) sections of the brain [15].

Cognitive decline has the following characteristics due to the affected areas relating to the patient’s personality-behavior and reason [16]:

1) In the type of disease that mainly affects behavior: limiting inhibitions (resulting in socially unacceptable behavior), apathy/inactivity, loss of understanding of others’ feelings, impulsive-stereotyped-repetitive behavior, and changes in diet

2) The type that mainly affects speech is difficulty in speaking, finding the right word and object name, grammatical errors, and problems with understanding the language.

When it comes to treating dementia, it is done with pharmaceuticals and non-pharmaceutical treatments. Existing pharmaceutical therapies are central cholinesterase inhibitors (AchEIs) and memantine. Specifically, AchEIs (Donepezil, Rivastigmine, Galantamine) have been widely used in daily clinical practice for years to treat Alzheimer’s disease and other forms of dementia [8].

According to researchers, these non-medicinal treatments are divided into two categories, compensatory strategies and restorative strategies. Compensatory strategies relate to the use of internal methods, such as mental imaging, diaries, data categorization, while the latter ones relate primarily to exercises of attention, memory, memory therapy, etc. [17]. According to the guidelines of the National Institute of Clinical Excellence (NIQE) of the United Kingdom, in addition to memory exercises, non-pharmaceutical interventions for people with dementia may include (Dementia: supporting people with dementia and their careers in health and social care | Guidance | NICE, 2006)

a. Aromatherapy

b. Multifocal excitation

c. Therapeutic use of music or dance

d. Animal-assisted therapy

e. Massage

Non-drug therapies also include cognitive functioning therapies, which include cognitive training, mental empowerment, mental rehabilitation, as well as speech therapy, occupational therapy and physical activity. [8].

Promotion of Health Quality of Patients with Dementia

Dementia is known to have many organic symptoms and complications that health professionals are called upon to deal with and even prevent, thereby promoting the quality of life of these patients [18]. These interventions are summarized as follows:

Interventions to improve mental functioning

There are various procedures for dealing with dementia mentally. The most common interventions are:

Early memory loss support groups: They aim at supporting the educational, social, and emotional needs of the individual, as well as the family, in the early stages of dementia, with the main problem being memory loss, as well as providing a safe and positive environment for the demented person to express his feelings of any loss in order to learn to build on his strengths and maintain his self-esteem, including designing his future needs [19]. We could propose a list of the patient’s memory loss, referring to people he daily meets, assisted by people he trusts; they will keep his fears and emotions hidden [20].

Methods of serving personal expression: Efforts to rehabilitate and/or stabilize (memory exercises, manual/creative activities, enhancement of aesthetic-motor functions, and selfservice therapy) have proven capable of improving cognitive abilities, psychomotor functionality, affective and emotional wellbeing and hypersensitivity [19]. Other methods of improving communication as well as personal expression are considered to be their speech and social communication in support groups, written speech in writing workshops; when group participants write and remember while expressing themselves in a visual form through art therapy, it improves their communication [21].

Interventions to improve functionality: First and foremost, a person suffering from dementia is able feed himself for as long as possible. Caregivers need to take care of the environment during meals, the meal itself, their approach to lunch, the assessment of mental and physical abilities, the patient’s ability to eat independently, the appetite of the demented person and his emotional state. Short, step-by-step instructions may be needed (Plati, 2004). Also, institutions having carefully designed environments, whether indoors or outdoors, help reduce disturbed

behavior such as anger, impatience and wandering. Poorly designed environments, on the other hand, can accelerate anger and contribute to disorientation and confusion [19].

A fairly common problem regarding people with dementia is urinary and/or faecal incontinence. Urinary and/or fecal incontinence can have detrimental effects on fitness, psychosocial functioning, and cost of care, and thus, it constitutes an additional natural, emotional, and financial burden on the care of dementia patients. Beyond any therapeutic interventions for incontinence, behavioral regimens can be applied to improve it [22]. They are separated into interventions dependent on the patient and can be applied in the early stages of the disease, such as pelvic floor exercises, special equipment biofeedback procedures, behavioral training and bladder training, and those dependent on the caregiver and it can be applied even to advanced stages of the disease such as habits training, scheduling toilet visits on a regular basis, positive reinforcement, techniques such as light strokes over thighs and trunk bent forward during urination [23]. Continuous bladder catheterization should be avoided unless there are complications, inflammation of the wound or unacceptable behavioral disorders resulting from incontinence (Plati, 2004).

Interventions to improve behavioral problems: It is necessary to have a physical examination so as to rule out any physical illness and complete psychiatric evaluation. Delusions and hallucinations as well as depression were equally common in men, and therefore, it is likely to be treated with antipsychotic treatment [13]. While setting realistic goals and organizing plans, encouraging caregivers to reward themselves and others for achieving goals, along with continually assessing and modifying treatment plans like art therapy are some principles in non-pharmaceutical interventions [22]. The healing process should also be addressed to the caregivers. Nurses should be encouraged to educate caregivers and patients about the diagnosis, prognosis, pharmaceutical and non-pharmaceutical strategies that are likely to prove very useful, recognizing that caregivers have an important role to play in managing their problems (Muyas, 2011).

Conclusion

Dementia is a major medical and social problem nowadays, and therefore, the planning of state actions should focus on prevention and management, with the support and expansion of support agencies. Advances in life sciences increase the likelihood of understanding the complex risk factors as regards dementia and suggest appropriate therapeutic interventions. Simultaneously, several techniques are being planned and delved into the experience of dementia; it allows an assessment of the ways from which caregivers can enhance the quality of life of people suffering from that condition.

In addition, social policy development for the elderly suffering from dementia is considered essential nowadays as this problem is continuously increasing. In addition, everyday clinical practice beyond any interventions, attitudes, behaviors and both moral and ethical problems that are related to and resulting from it requires full respect for human life. It also requires love, being human and giving your best to the fellow man.

Acknowledgement

None.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest.

References

- Babiniotis G (2009) Etymological Dictionary of the New Greek Language, Lexicology Center, Athens.

- Mougias A (2011) Dementia and Quality of Life in Old Age. Doctoral Thesis, University of Ioannina, School of Medicine, Ioannina.

- Paplos KG, Havaki Kontaxakis MI, Kontaxakis BP (2005) Prevention of Alzheimer's Disease and Other Defective Syndromes, in Preventive Psychiatry & Mental Health, BETA Publications, Athens, pp. 513-524.

- Wimo A, Jönsson L, Bond J, Prince M, Winblad B (2013) The worldwide economic impact of dementia 2010. Alzheimers Dement 9(1): 1-11.

- Dardiotis E, Kosmidis MH, Yannakoulia M, Hadjigeorgiou GM, Scarmeas N (2014) The Hellenic Longitudinall Investigation of Aging and Diet (HELIAD): rationale, study design, and cohort description. Neuroepidemiology 43(1): 9-14.

- Yfantopoulos G, Sarris M (2001) Health-Related Quality of Life: Measurement Methodology.

- Farina N, Pages TE, Daley S, Brown A, Bowling A, et al. (2017) Factors associated with the quality of life of family carers of people with dementia: a systematic review. Alzheimers Dement 13: 572-581.

- Sakka P, Efthimiou A, Danasi E, Karpathou N, Vamvakari E, et al. (2015) Handbook for Health Professionals-Basic authorities for dementia. Bodosaki Foundation, Athens.

- L Kourkouta, E Hatzidimitriou, A Trikaliotou, S Andrea (2002) Nursing Problems of Elderly Patients with Alzheimer's Dementia and Their Treatment at Home. Proceedings of the 2nd Panhellenic Interdisciplinary Conference on Alzheimer's Disease and Related Disorders, Thessaloniki.

- McKhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, Hyman BT, Jack CR, et al. (2011) The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer's disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimer's & Dementia. Alzheimers Dement 7(3): 263-269.

- Hyman BT, Creighton HP, Beach GT, Bigio EH, Cairns NJ, et al. (2012) National Alzheimer's Institute Association guidelines for neuropathologic assessment of Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement 8: 1-13.

- ICD-10 (1992).

- Tsolaki M (2005) Early diagnosis and treatment of dementia.

- Misculis KE, Heaf TC (2012) Netters-Summary of Neurology, Curated by Greek Edition, Papathanassopoulos P, Gotsis Editions, Patras.

- Bradley PS, Sheldon W, Wooster B, Olsen P, Boanas P, et al. (2009) High-intensity running in English FA Premier League soccer matches. J Sports Sci 27(2): 159-168.

- Lezak M, Howieson D, Loring D (2009) Neuropsychological Assessment, Editing the Greek Edition: Messini L, Kosmidou M, Papathanasopoulos P, Gotsis Editions, Patras.

- Sitzer DI, Twamley EW, Jeste DV (2006) Cognitive training in Alzheimer's disease: a meta-analysis of the literature. Acta Psyciatr Scand 14(2): 75-90.

- L Kourkouta, Ch Iliadis, A Monios (2018) Impact of bovine spongiform encephalopathy in human health. Scientific Chronicles 23(1): 51-58.

- Raya A (2004) Mental Health Nursing (4th Edn), I. Parisianou, Athens.

- Monios A, Iliadis X, Kourkouta L (2017) Protection from Prions. 44th Panhellenic Nursing Conference of ESSN, Naxos,10.

- Reppa E (2018) Investigation of the burden and quality of life of atypical dementia caregivers in the city of Patras. Bachelor's thesis. Graduate Program in Public Health, School of Medicine, School of Health Sciences, University of Patras, Patras.

- Kourkouta L (2016) The Social Exclusion of Elderly. Journal of Healthcare Communications 1(3:21): 1-3.

- Pagkaltsos A (2001) Gerontology and Geriatrics elements. Technological Educational Institute of Thessaloniki, Thessaloniki.

- Lambrini Kourkouta, Aikaterini Frantzana, Christos Iliadis, Monios Alexandros (2016) Health Problems of the Elderly Monograph, Scholar’s Press, Saarbrucken, Germany.

- Dementia: supporting people with dementia and their careers in health and social care.

- Chrysanthi D (2004) Gerontological Nursing. Issue FI Parisianou, Athens.

- Primary Health Care Workshops «G Papadakis », Publisher S Papas, Volume B: 145-156.

-

Aikaterini Frantzana. Patients with Dementia Assessing their Quality of Life. Arch Neurol & Neurosci. 6(5): 2020. ANN.MS.ID.000648.

-

Dementia, Brain Neurons, Central Nervous System, Aging and Diet, Mild Mental Disorder, Physical and Mental, Organic or Metabolic Disorders, Memory, Thinking, Orientation, Comprehension, Performing Arithmetic, Learning Ability, Language and Judgment.

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.