Research Article

Research Article

Efficacy of a Therapuetic Program for Memory/ Neuropsychological Deficits in a Mild Cognitive Decline/Dementia Population

Barbara C Fisher1* and Danielle Szokola2

1Clinic Director, United Psychological Services, USA

2Director of Assessment Program, United Psychological Services, USA

Barbara C Fisher, Clinic Director, United Psychological Services, USA.

Received Date: September 24, 2018; Published Date: October 15, 2018

Abstract

This is an ongoing study using a population of adults who have been evaluated and diagnosed with mild cognitive decline/ dementia. Adults ranging in age from 34 to 90 years old, with more of the population falling within the range of 60 to 80 years, were typically referred for evaluation by their primary care physician or treating specialist (neurologist or cardiologist). They participated in a treatment program completed in an outpatient therapeutic setting employing the use of a specific individualized neurocognitive training program. Patients received cognitive behavioral therapy as well as neurocognitive training in the context of a therapy session twice per week. The program consists of game like activities that are individually designed based upon the neuropsychological evaluation results. Patients are re-evaluated within six months to a year, the program is changed to accommodate the results of re-evaluation. This is an ongoing study published last in May of 2018 [1].

Introduction

The effectiveness of a cognitive therapy/training program (that is individually designed) to remediate neuropsychological deficits (primarily memory) in a diagnosed mild cognitive decline/dementia population at a private clinic was assessed. Neuropsychological evaluation was administered prior to and following therapeutic intervention and results were compared. This study has been ongoing since 2011. The literature review was provided in the earlier 2018 publication.

Method

Adults were referred for assessment of memory difficulties and diagnosed with dementia (age 34 to 90 years, n= 93). There are a total of 36 males and 57 females. The common age range was between 60 and 80 years. Patients have been diagnosed with sleep apnea, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, as well as a variety of neurological disorders (including Parkinson’s, Multiple Sclerosis, Huntington’s Chorea, as well as effects from cancer treatment/ radiation). Education ranged from high school to graduate degrees. Individual are compared relative to themselves with pre and post-testing. Many, if not all of the patients were on some type of medication.

All patients were diagnosed and treated for predominantly memory deficits. Multifactorial dementia was the common diagnosis or mild cognitive decline in addition to early onset Alzheimer’s or Cardiovascular dementia, 6% were diagnosed with early onset dementia, 2% were diagnosed with late onset dementia, 58% with Cardiovascular dementia, 9% with amnestic disorder, 13% with mild cognitive decline and 12% with multifactorial dementia to account for other origins. There are over 200 activities and games to choose from. An individualized treatment program is created based upon the results of the initial neuropsychological evaluation from over 200 games and activities. The therapist uses this initial treatment plan and then modifies the plan as needed through the course of therapy.

Testing employed the following test measures: The Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status (RBANS), Memory Assessment System (MAS), Doors and People Test, and Brief Visual Motor Test Revised (BVMT-R) and Wide Range Assessment of Memory and Learning (WRAML-2) were utilized to measure memory functioning pre and post treatment.

The RBANS has been used extensively for critical care and in research with patients diagnosed with cognitive deficits or dementia. The Doors and People is an accepted memory test for visual and verbal retrieval and recognition. The BVMTR has been used in the aged population as a measure of visual memory [2- 7]. The WRAML-2 has normative data that ranges from 5 to 85 years and is an accepted measure of memory function through the lifespan [8-9].

Memory is primarily addressed for treatment; visual and verbal memory, short term and working memory, as well as recognition and retrieval. The impact of executive deficits is addressed depending upon the patient’s need; selective attention, problem solving, cognitive rigidity, integration and poor sequential processing. Treatment includes cognitive behavioral therapy to manage life’s ongoing issues as well as modifiable factors of exercise, good sleep, fluid intake and nutrition. The importance of remaining active and social with friends is stressed in treatment. On average a total of 6 months to 1 year elapsed between pre and post testing. Following post-testing changes are made to the program based upon evaluation results and the patient is re-evaluated again in six months to one year for ongoing therapy.

Results

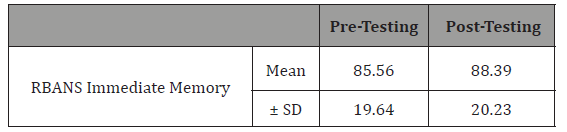

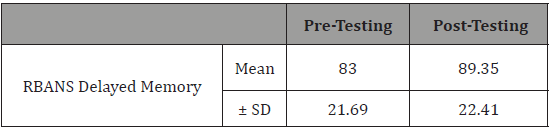

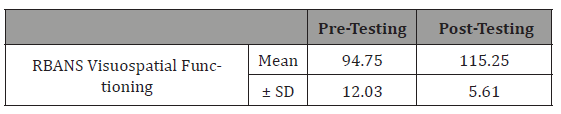

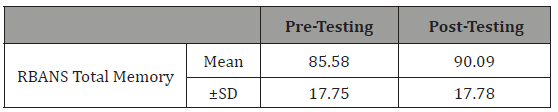

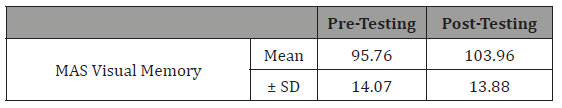

Areas of short-term, delayed, visual, verbal, and overall memory, as well as visuospatial functioning evaluated improved following treatment. Paired samples t-tests revealed significant differences between pre and post treatment scores on the RBANS for immediate memory (p= 0.022), delayed memory (0.004), visusospatial functioning (0.014) and overall memory (p= 0.001), as well as on the MAS for visual memory (p= 0.009).

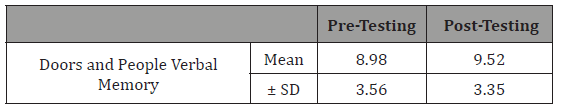

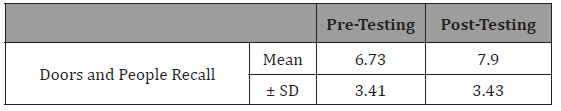

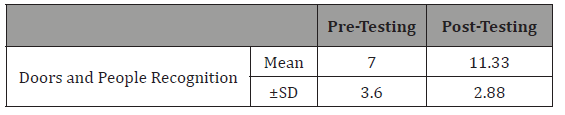

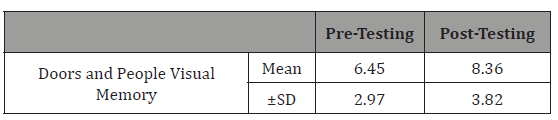

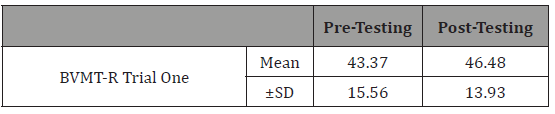

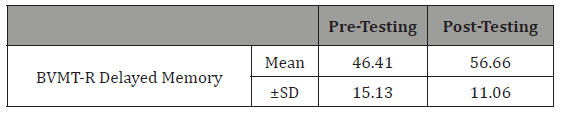

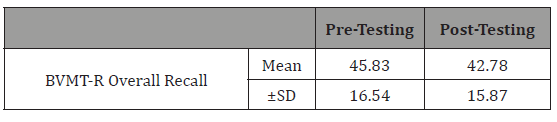

Significant findings were also present on the Doors and People Test for the People Test, involving verbal memory (p= 0.047), recall (p=0.007) and recognition (p= 0.023). On the BVMT-R there was a significant difference for the initial learning trial (p= 0.011), delayed recall (p= 0.035) and overall recall (p= 0.023).

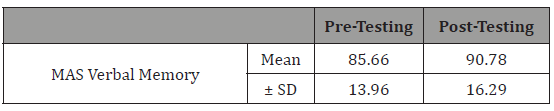

Marginally significant differences occurred on the MAS verbal memory (p= 0.054) and the Doors Test, involving visual memory (p= 0.052) (Tables 1-13).

Table 1: Effect of cognitive training on immediate memory performance.

Table 2: Effect of cognitive training on delayed memory performance.

Table 3: Effect of cognitive training on visuospatial functioning.

Table 4: Effect of cognitive training on overall memory performance..

Table 5: Effect of cognitive training on visual memory performance.

Table 6:Effect of cognitive training on verbal memory performance.

Table 7:Effect of cognitive training on verbal memory performance.

Table 8: Effect of cognitive training on recall.

Table 9:Effect of cognitive training on recognition.

Table 10:Effect of cognitive training on visual memory performance.

Table 11: Effect of cognitive training on visual memory performance.

Table 12:Effect of cognitive training on delayed memory performance.

Table 13:Effect of cognitive training on overall recall.

Discussion

Neurocognitive training using an individualized treatment program appears to be an effective intervention providing positive benefits in the form of improved memory function. This was seen on pre and post-testing where each patient provided their own controls. Re-evaluation typically occurred at the same time of day and often with the same examiner. Patients report improved daily functioning suggesting the benefit of this program to address the escalating concern of mild cognitive decline and dementia.

Conclusion

Findings continue to indicate that memory function can be improved using neurocognitive training within the context of a therapeutic setting using a patient specific individualized program. Evaluation occurring every six months to one year demonstrates ongoing efficacy of this program that combines cognitive behavioral therapy with neurocognitive training to improve memory functioning while helping individuals age gracefully. Important modifiable risk factors are continually addressed to provide a wellrounded therapeutic program to address the problem of cognitive decline/dementia.

Limitations of the Study

The study lacks a patient control group given that this is a clinical study, completed in an outpatient setting with the goal of treating dementia and memory deficits. There is always the risk of a practice effect given the familiarity with the measure however in testing individuals with memory difficulties this becomes less of an issue. Six months has been the general known rule for practice effects no longer being considered as a variable which is specifically noted in various test manuals. On the RBANS there was a largely absent practice effect after one year, mean re-test scores increased by 5 points for the index scores excluding language which was 2 points after 39 weeks. Depending upon the form, there was a gain of 2 to 4 raw score points for the BVMT-R after 56 days in healthy participants. On the Doors and People Test there was no change in the brain injured group over time [3-7]. Testing typically was six months or greater. Medication and sleep are additional variables that can impact function and are continually tracked in treatment although not addressed statistically in this study.

Acknowledgemnet

None.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest.

References

- Fisher BC, Szokola D (2018) The efficacy of neurocognitive training upon a diagnosed mild cognitive decline/dementia population in a clinical setting: Ongoing study since 2011. Neurol Sci J 2(1): 1-4.

- Hammers DB, Atkinson TJ, Dalley BC, Suhrie KR, Beardmore BE, et al. (2017) Relationship between 18F-flutemetamol uptake and RBANS performance in non-demented community-dwelling older adults. Clin Neuropsychol 31(3): 531-543.

- Duff K, Schoenber MR, Patton D, Mold J, Scott JG, et al. (2004) Predicting change with the RBANS in an elderly sample. Journal of International Neuropsychology Soc 10(6): 828-834.

- Baddeley AD (2004) The doors and people test: A test of visual and verbal recall and recognition, Bury St-Edmunds UK: Thames Valley Test Company, England.

- Wilson BA, Watson PC, Baddeley AD, Emslie H, Evans JJ (2000) Improvement or simply practice? The effects of twenty repeated assessments on people with and without brain injury. J Int Neuropsychol Soc 6(4): 469-479.

- Mac Pherson SE, Turner MS, Bozzali M, Cipolotti L, Shallice T (2016) The doors and people test: the effect of frontal lobe lesions on recall and recognition memory performance. Neuropsychology 30(3): 332-337.

- Duff K (2016) Demographically-corrected normative data for the Hopkins Verbal Learning Test-Revised and Brief Visuospatial Memory Test-Revised in an Elderly Sample. App Neuropsycholo Adult 23(3): 179-185.

- Sheslow D, Adams W (2003) Wide Range Assessment of Memory and Learning, Second Edition. Psychological Assessment Resources.

- Atkinson TM, Konold TR, Glutting, JJ (2008) Patterns of memory: a normative taconomy of the Wide Range Assessment of Memory and Learning-Second Edition, (WRAML-2) 2008. Journal of Int Neuropsychological Society14 (5): 869-877.

-

Barbara C Fisher, Danielle Szokola. Efficacy of a Therapuetic Program for Memory/Neuropsychological Deficits in a Mild Cognitive Decline/Dementia Population. Arch Neurol & Neurosci. 1(2): 2018. ANN.MS.ID.000510.

-

Neuropsychological deficits, Mild Cognitive decline, Dementia population, Neurologist, Behavioral therapy, Neuropsychological evaluation, Population, Memory, Neurocognitive, Medication, Sleep, Brain injury, Cognitive training, Visual memory, visuospatial functioning, Recall, Recognition

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.