Mini Review

Mini Review

Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy in the Treatment of Recurrent Isolated Sleep Paralysis

Aleksey Igorevich Melehin*

PhD in Psychology, associate professor, Stolypin humanitarian Institute, Moscow, Russia

Aleksey Igorevich Melehin, Associate Professor, psychoanalyst, clinical psychologist of the highest qualification category, somnologist, cognitive behavioral therapist. Humanitarian Institute named after P. A. Stolypin. 107076, Moscow, Bukhvostova Street, 1-ya, d. 12 / 11, bldg. 20, Moscow, Russia.

Received Date: August 02, 2021; Published Date: September 13, 2021

Mini Review

In Russia, approximately every fifth person has experienced a state of sleep paralysis, which can be Isolated Sleep Paralysis or in the structure of post-traumatic stress disorder (for example, the loss of a significant person, a serious illness of a child), a large episode of depression and a reaction of grief (for example, in the process of separation) [1,2]. Patients describe this condition as a feeling that “the body is asleep, and the brain is working.” It is as if they are seeing a “dream in a dream”. When they wake up, they can’t move their arms or legs, they feel that they are being held by their arms/legs, they are being pressed on their chest, they are holding their mouth. They can only open their eyes and observe the difference of vision: animals, “a person without a face”, close people, dead people, “strange silhouettes”. What they saw is interpreted as a paranormal, religious experience, supernatural attack, near-death experience, “feeling that they are going crazy”, abduction/contact with someone and something. Patients begin to move the body by force, and as soon as they manage to move, push on something, the condition abruptly passes. They get up, walk and go back to bed and fall asleep. In the morning, patients forget a lot or everything, during the day there may be residual memories of the episode with a tendency to “symbolic interpretation” (dramatic mythical scenarios), the search for causes. There is somatization in the form of headache, irritable bowel, pain syndrome, fatigue. The anxious expectation increases (fear of the night, a repeat episode) [1]. The intense sensory and perceptual experiences suffered cause postepisodic distress from sleep paralysis (=SP postepisode distress), which leads to the development of a spectrum of avoidant and reinsurance behavior in the patient [2].

Speaking about the tactics of treating sleep paralysis, at the moment there are several options for pharmacological (for example, the use of escitalopram) and psychotherapeutic treatment for chronic and severe cases, but none of them to this day has irrefutable evidence of effectiveness. Test of the mental status of a patient with sleep paralysis is carried out using: PHQ-SADS, ISI, Sleep Paralysis Post-Episode Distress Scale, DASS-21 and Sleep Paralysis Experiences and Phenomenology Questionnaire (SPEPQ). The patient is also asked to keep a diary of episodes of sleep paralysis: the perceived duration (sec / min), the fear associated with the attack, and the disorder caused by hallucinations (on a tenpoint scale).

In our daily practice, we often use the protocol of muscle relaxation before bedtime for patients with sleep paralysis (Focused-Attention Meditation Combined with Muscle Relaxation therapy). It is aimed at teaching patients to perform four steps during an episode [3]:

• Reassessment of the meaning of the attack-a reminder to yourself that the experience is ordinary, favorable and temporary, and that hallucinations are a typical byproduct of dreams.

• Psychological and emotional distancing-reminding yourself that there is no reason for fear or anxiety and that fear and anxiety will only worsen the episode.

• Meditation of internal focused attention - focusing their attention inward on an emotionally engaging, positive object (for example, a memory of a loved one or an event, a hymn / prayer, God, a positive experience, to name 5 things that bring pleasure).

• Muscle relaxation - muscle relaxation, avoiding breath control.

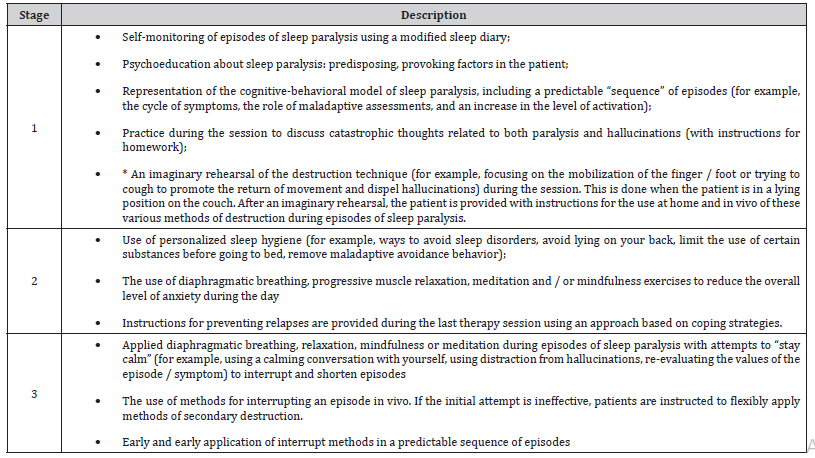

Recently, a protocol of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) for the treatment of recurrent isolated Sleep paralysis (CBT-ISP) was proposed, which is aimed at reducing post-episodic distress from sleep paralysis: minimizing anxious ruminations about sleep, difficulty falling asleep, fear of falling asleep, improving cognitive functioning and mood background during the day. In Table 1, we present the structure of this protocol [2] (Table 1).

Table 1:Protocol of cognitive behavioral therapy for the treatment of recurrent isolated sleep paralysis by B. Sharless and K. Doghramji.

As can be seen from Table 1, both forms of psychotherapy overlap in many ways. Both protocols pay special attention to various forms of relaxation, re-evaluation of symptoms, switching attention away from the content of the episode and the practice of interrupting while patients are in the supine position. It should also be noted that both approaches are based on cognitive behavioral models of panic disorder. The protocol of muscle relaxation before bedtime for patients with sleep paralysis prevents the patient from trying to move, whereas CBT actively encourages these attempts to directly disrupt episodes and distract attention from potentially frightening symptoms (for example, hallucinations). The first psychotherapeutic protocol is not aimed at breathing techniques, while in CBT it is as a potential source of relaxation that can be used “at the moment” of the attack. He is also against the use of such forms of relaxation as prayers, as he sees this as a reinsurance behavior that reinforces dysfunctional beliefs about the episode. The effectiveness of CBT. There is a decrease in episodes of sleep paralysis, minimization of anxious rumination about sleep, difficulty falling asleep, fear of falling asleep, improvement of cognitive functioning and mood background during the day. It also increases the sense of control over the episodes. Remission is 4-6 months [2].

Acknowledgement

None.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest.

References

- Ayed S, Daghfous F, Guermazi K, et al. (1991) Causes of blindness in Tunisian children. Rev Int Trach Pathol Ocul Trop Subtrop Sante Publique 68: 123-128

- Singh RB, Thakur S, Ichhpujani P (2018) Traumatic rosette cataract. BMJ Case Rep 11(1): e227465.

- Du Y, He W, Sun X, Lu Y, Zhu X (2018) Traumatic cataract in children in eastern China: Shanghai pediatric cataract study. Sci Rep 8(1):2588.

- Ramkumar H, Basti S (2008) Reversal of bilateral rosette cataracts with glycemic control. Scientific World Journal 8: 1150-1151.

- Rofagha S, Day S, Winn BJ, Ou JI, Bhisitkul RB, et al. (2008) Spontaneous resolution of a traumatic cataract caused by an intralenticular foreign body. J Cataract Refract Surg 34(6): 1033-1035.

- Avasthy P, Gupta RB (1958) Traumatic cataract. Br J Ophthalmol 42(4): 240–241.

- Petermeier K, Szurman P, Bartz-Schmidt UK, Gekeler F (2010) Pathophysiology of cataract formation after vitrectomy. Klin Monatsbl Augenheilkd 227(3): 175-180.

- Moreschi C, Da Broi U, Lanzetta P (2013) Medico-legal implications of traumatic cataract. J Forensic Legal Med 20(2): 69-73.

- Shah MA, Shah SM, Shah SB, Patel CG, Patel UA (2011) Morphology of traumatic cataract: does it play a role in final visual outcome? BMJ Open 1(1): e000060.

- Brini A, Porte A, Stoeckel ME (1963) Resorption of necrotic lens material by a newly formed lens capsule in certain types of cataract. Nature 200: 796-797.

- Neumayer T, Hirnschall N, Georgopoulos M, Findl O (2017) Natural course of posterior subcapsular cataract over a short time period. Curr Eye Res 42(12): 1604-1607.

- Bansal A, Fenerty CH (2020) Spontaneous resolution of a rapidly Formed dense cataract following Nd: YAG laser peripheral Iridotomy in a case of Pigmentary Glaucoma. J Glaucoma 29(4): 322-325.

- Matalia J, Kasturi N, Anaspure H, Shetty BK, Matalia H (2015) Isolated posterior capsular split limited by Weiger's ligament after blunt ocular trauma in a child mimicking posterior lenticonus. J AAPOS 19(6): 557-558.

- Lee SI, Song HC (2001) A case of isolated posterior capsule rupture and traumatic cataract caused by blunt ocular trauma. Korean J Ophthalmol 15(2): 140-144.

- Wolter JR (1963) Coup-contrecoup mechanism of ocularinjuries. Am Ophthalmol 56: 785-796.

- khokhar SK, Pillay G, Dhull C, Agarwal E, Mahabir M, Aggarwal P (2017) Pediatric cataract. Indian J Ophthalmol 65(12): 1340-1349.

- Medina A (2018) Prevention of myopia by partial correction of hyperopia: a twins study. Int Ophthalmol 38(2): 577-583.

- Khatry SK, Lewis AE, Schein OD, M D Thapa, E K Pradhan, et al. (2004) The epidemiology of ocular trauma in rural Nepal. Br J Ophthalmol 88: 456-460.

- Alfaro DV, Jablon EP, Rodriguez Fontal M, Simon J Villalba, Robert E Morris, Michael Grossman, et al. (2005) Fishing-related ocular trauma. Am J Ophthalmol 139: 488–492.

-

Aleksey Igorevich Melehin. Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy in the Treatment of Recurrent Isolated Sleep Paralysis. Arch Neurol & Neurosci. 11(2): 2021. ANN.MS.ID.000760.

-

sleep paralysis, stress disorder, cognitive functioning.

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.