Review Article

Review Article

Brief Case Report: Neurocognitive Assessment of a Child’s Ability to Benefit from Psychotherapy and Strategy for Court Testimony

Stephen E Berger* and Bina Parekh

Chicago School of Professional Psychology, California, USA.

Stephen E Berger, Chicago School of Professional Psychology, Irvine, California, USA.

Received Date: December 09, 2019; Published Date: December 16, 2019

Abstract

This brief case report encompasses three components. First, a legal question was raised as to whether this 12-year old boy had neurocognitive deficits that would prevent him from being able to benefit from psychotherapy. Second, the neurocognitive assessment that was conducted enabled a comparison of his neurocognitive intellectual assessment on the newest version of the children’s edition of the Wechsler scales (WISC-IV) with concurrent, and past performance on the prior edition of the Wechsler scales (WISC-III). These comparisons raised the issue of the Flynn effect, and how that affected the interpretation of his neurocognitive functioning at age 12 compared to age 10. Finally, third, a myriad to formal psychological test results needed to be compressed for testimony in Court. This report includes a delineation of that legal strategy. The extensive documents regarding past assessments revealed that over the 6 years plus since formal assessments had begun, that this child was showing an increase in emotional distress as he confronted his neurocognitive challenges in the classroom. Detailed current neurocognitive assessment demonstrated his strengths in reasoning ability that had not been fully appreciated previously. As a result of the proper comparison of the child’s neurocognitive functioning, it was determined that he was capable of benefitting from formal psychotherapy, and that service was no longer denied to him.

Keywords: GAI: General Ability Index; FSIQ: Full Scale IQ Score; VCI: Verbal Comprehension Index; PRI: Perceptual Reasoning Index; WMI: Working Memory Index; PSI: Processing Speed Index

Introduction

“K … has below average IQ.. and language deficits. In both expressive and receptive domains along with auditory processing problems … psychotherapy can only highlight K’s weaknesses. Psychotherapy would not be recommended for this student.” With those words in the formal report of the assessing psychologist for the County Department of Mental Health, psychotherapy services were denied as a covered benefit to this 12-year-old child. His case came to the attention of the senior author when the attorney representing the child sought an independent, current assessment of K’s neurocognitive functioning as a possible counter to the assertions of the psychologist for the County.

Of concern to the senior author was that K was participating in individual psychotherapy and according to his psychologist was verbally participating in the therapy and benefiting from the therapy. Sadly, the psychologist indicated he was not comfortable in a Court setting and did not want to testify. The child’s attorney did not want to proffer such testimony and needed an independent evaluation. A second concern was how to present to the Court the massive amount of formal assessment data that was available on this child. The amount of individual test scores over the past 6 plus years would present a complex visual chart for the Judge. More importantly, an examination of the formal, written reports that had been produced clearly documented that K was fully capable of engaging in verbal communication regarding his thoughts, feelings and emotional distress.

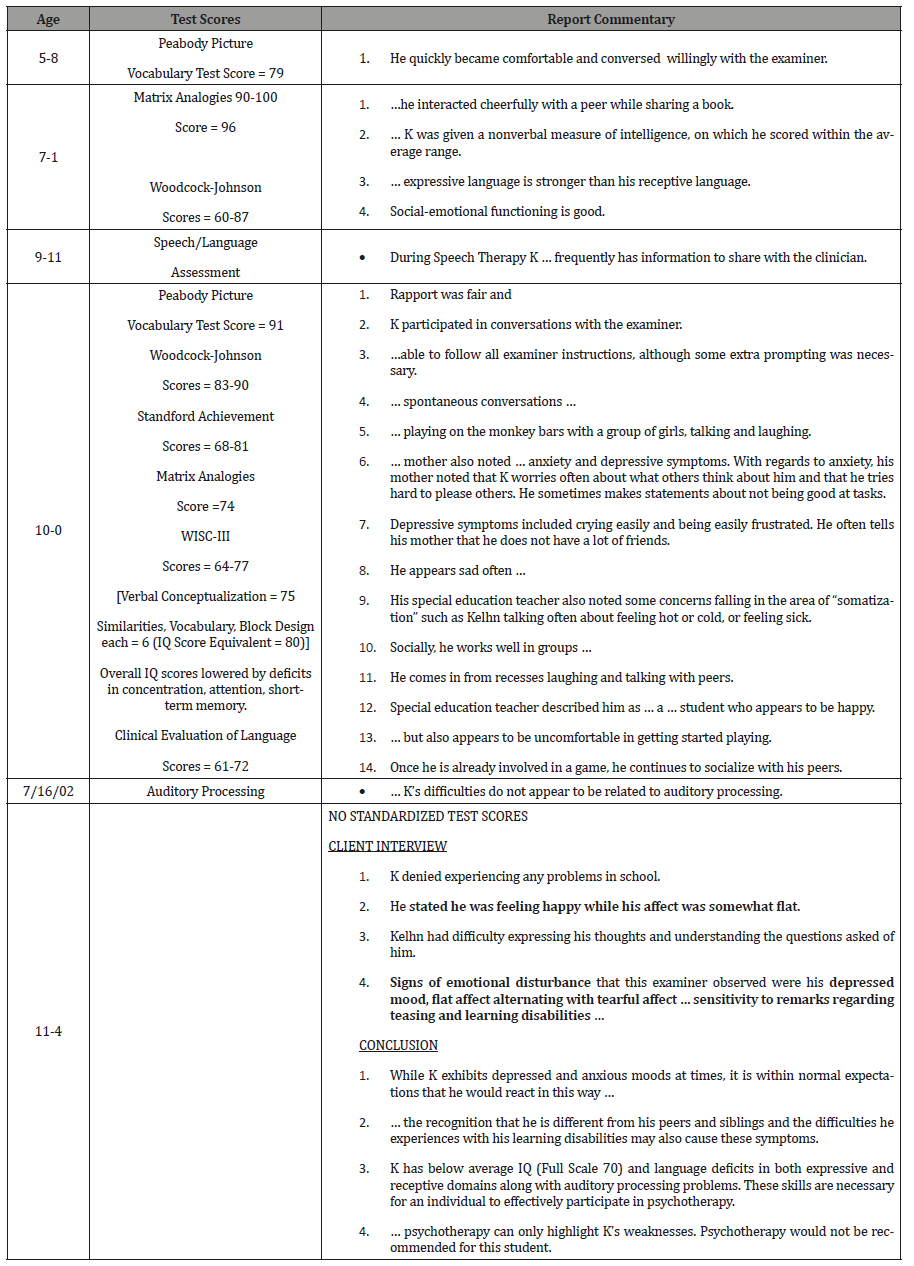

Therefore, the decision was made to present the Judge with a chart that indicated the tests administered each year, but no scores were provided. Instead, next to the names of the tests were the comments and observations of the evaluators. Certain words bolded so they would stand out to the Judge. Those words demonstrated that K could express himself verbally in regard to his thoughts and feelings as well as the increased emotional distress he felt from year to year. After all other information was to be presented to the Judge, the chart would be presented again, now including the test scores. That was easy to do as a Power Point presentation, but for purposes of this presentation, only that final chart (Table 3) is presented at the conclusion of this article so the version without the test scores is not presented here so as not to basically duplicate two versions of the chart.

Thus, the strategy was to first prime the Judge regarding, in a sense, who was this child – his personality, his feelings, his struggles, his interactions with examiners and with other children, and not to overwhelm the Judge with years of test scores. At that point, the plan was to present the Judge with the most recent neurocognitive test scores only. Those scores consisted of the results of the County’s administration of the newest edition of the Wechsler scales, the WISC-IV [1], compared to the senior author’s administration of the WISC-III [2]. By administering the WISC-III, two comparisons could be conducted. First, K’s most recent WISC-III scores could be compared to his prior scores (at a younger age), Second, his WISCIII scores could also be compared to the “more difficult” WISC-IV scores. By more difficult, what is meant in an overly simplistic sense is that the norms for the WISC-IV are in a sense tougher than the norms from earlier editions. The reason for that is what is termed the Flynn effect [3,4], which would also have to be explained to the Judge. In brief, the Flynn effect is the phenomenon that whenever the norms on IQ tests are brought up to date, the normative scores rise, and Flynn found that this has been happening for generations, all over the world. Thus, in a simplistic sense, if one is going to keep up with the population, they are going to have to get more items correct (or higher rated scores on individual items). If one does not keep up with the population, their Full-scale IQ score will appear to decline (usually in a range of 5-8 points).

Thus, in evaluating K’s neurocognitive functioning from age 10 to the current assessment at age 12, it is critical to understand that he would now be compared to the neurocognitive abilities of 12 year-olds. Thus, in order to simply maintain his relative standing in neurocognitive functioning, be would need to “keep up” with his peers – with what 12-year old children can do. In addition, the newer version of the Wechsler would not only pit him against what the average 12-year old can do, but also employing more stringent norms, meaning he would be working against two factors affecting his neurocognitive score assessment.

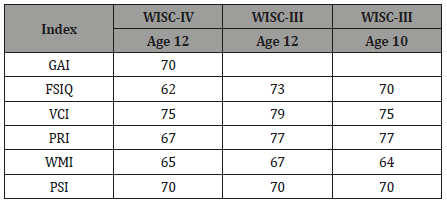

Table 1 presents K’s scores on the Wechsler-III when he was 10 years old, and now at age 12 where he is being compared to 12-year-old children. In addition, Table 1 also presents his scores on the newer Wechsler, the WAIS-IV. There are several aspects of the Table that draw immediate attention. First, it will be seen that not only has he kept up over the past two years with the 12-year olds on the WISC-III, but there are signs that he is catching up in overall neurocognitive functioning. Second, it will be noticed that there seems to be an anomaly in his Full-scale IQ score on the WISCIV. Consequently, Table 1 includes a score for General Ability Index (GAI) (Table 1).

Table 1:Depiction of K’s scores on WISC-III at AGE 10 and AGE 12 and on WISC-IV at age 12.

Moreover, there was a trend in SSA patients for higher risk of sustained severe disability (EDSS≥7) (HR 5.0(0.9-27), p=0.06. Another observation was that the use of Rituximab reduced the risk of relapse (HR 0.27 (0.10, 0.77), p=0.003 compared to no DMT.

When the anomaly in his Full-scale IQ score on the WISC-IV was noted, contact was made with the Psychological Corporation (Pearson Assessments). They immediately explained that the WISC-IV modified the way IQ scores were now computed – making the biggest change in how such scores were computed since the Wechsler-Bellvue [5] contrasted with the Stanford-Binet [6]. Thus, Working Memory and Processing Speed counted more heavily in Full Scale IQ score calculation than ever before. This information was laid out in detail in their publication: Technical Information Report#4 [7]. Specifically, this document explained that Full Scale IQ scores are not appropriate for children who exhibit the kinds of learning difficulties exhibited by children such as K and that the General Ability Index is more appropriate.

The following paragraphs are quoted directly from Technical Information Report #4 with emphasis added:

The WISC–IV FSIQ, however, includes (to a greater extent than the WISC–III FSIQ) the influence of working memory and processing speed, to reflect research that suggests both working memory and processing speed are important factors that contribute to overall intellectual functioning [8-12]. Recent research continues to confirm the importance of working memory and processing speed to cognitive ability and to refine knowledge about the nature of these relations [13-15].

When to Use the GAI

Presently, most school district policies continue to require evidence of an AAD in order to obtain special education services, and it was largely for this reason that the GAI was first developed. For some children with learning disabilities, attentional problems, or other neuropsychological issues, concomitant working memory and processing speed deficiencies lower the FSIQ. This is evident in Table 3 (see pages 9–10), which shows that FSIQ < GAI profiles were obtained by more than 70% of children.

While potentially clinically meaningful, this reduction in the FSIQ may decrease the magnitude of the AAD for some children with learning disabilities and make them less likely to be found eligible for special education services in educational systems that do not allow consideration of other methods of eligibility determination.

It also may be clinically informative in a number of additional situations to compare the FSIQ and the GAI, to assess the impact of reducing the emphasis on working memory and processing speed on the estimate of general cognitive ability for children with difficulty in those areas due to traumatic brain injury or other neuropsychological difficulties. This comparison may inform rehabilitation programs and/or educational intervention planning.

What could now be pointed out to the Judge was that Table 1 showed that when K was compared on the WISC-III to the 12- year old norms, he at least was keeping up with that group and possibly catching up in his neurocognitive development and functioning (3 point gain on Full Scale IQ score and 4 points on Verbal Comprehension Index score). While it could be argued that individually these are non-statistically significant gains in scores, that the combined total of a 7-point gain was meaningful. At the same time was the anomaly of the Full Scale IQ score on the WISC-IV. However, by applying the GAI correctly to K’s score, he was showing that at least in comparison to where he stood at age 10, even when compared to the norms for the 12-year olds on this tougher normed assessment of neurocognitive functioning, he was keeping up.

Discussion

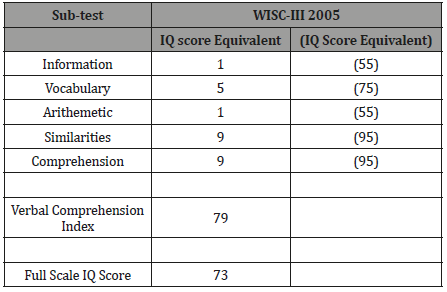

This is not the end of the story. As interesting as his scores were across ages 10 to 12 and on comparison of the older and newer versions of the Wechsler, even more revealing iss an analysis of his Scores an the WISC-III at age 12. These scores are presented in Table 2 for his verbal abilities scores. Table 2 reveals that K is demonstrating very significant variation in his scores on the verbal sub-tests of the WISC-III, There is a clear pattern to his scores. It is important to note that sub-test scores are reported as scaled scores, but those scores can be converted to IQ score “equivalents.” An examination of Table 2 reveals that K obtained scores in the Average range of intellectual functioning on sub-tests that reflect knowledge of reasoning about cultural norms as well as reasoning with familiar, verbal material. In contrast, his lowest performance, and what pulls his scores down is how far behind his age peers he is in concrete knowledge (information, Arithmetic) (Table 2).

Table 2:Depiction of K’s scores on WISC-III at AGE 10 and AGE 12 and on WISC-IV at age 12.

Finally, attention must be paid to Table 3, which presents the written commentary from the various examiners who evaluated K over the years of his early life. The earliest evaluation at age 5-8 included the comment, “…conversed willingly with the examiner.” At age 7-1, that evaluator wrote, “social-emotional functioning is good.” At age 9-11, the assessor wrote, “…participated in conversations with the examiner … spontaneous conversations … K worries often about what others think about him … depressive symptoms included crying eaily … appears sad …” These comments reveal that while he can come in from recess “laughing and talking with peers” that his neurocognitive difficulties in keeping up with concrete learning, while capable of at least average reasoning ability was taking a toll on his emotional well-being. The family had been wise to start him in psychotherapy, and in contrast to the County’s psychologist who wrote when he was 11-4 that “Psychotherapy would not be recommended …” that this was a child who very much would benefit from such help.

It should be duly noted that internalizing symptoms like anxiety and depression can affect working memory and processing speed performance in children [16]. It is often difficult to tease out the overlap between anxiety and depressive symptoms in children due to varying developmental trajectories modified by age, gender, and home environment [17]. For some children, anxiety can depress working memory scores since concentration and attentional skills are compromised [18]. Moreover, processing speed is also influenced by depressive and anxiety symptoms. It has been found that children who are depressed or have depressive symptoms have slower cognitive processing, which can alter retrieval and reaction times [19]. Thus, in the case of K, his neurocognitive deficits may have a psychological component in which his depressive/anxiety presentation may impact his working memory and processing speed. The interplay between K’s psychological and neurocognitive presentation further supports K’s need for psychotherapy (Table 3).

Table 3:Depiction of K’s scores on WISC-III at AGE 10 and AGE 12 and on WISC-IV at age 12.

Conclusion

There is a happy ending. The report and analysis of his test scores as delineated above was provided to K’s attorney and to the school district. At that point, the school district stepped up and took on the responsibility of providing the appropriate psychotherapy services for K. Initial follow-up indicated that he was continuing to benefit from his therapy as the availability of this service was no longer dependent on whether the family could provide the services. At this point, Table 3 is presented with the myriad of tests and scores over the years that had been utilized with K. This case highlights the importance of understanding that neurocognitive functioning is more complex than just a score or set of scores. What is critical is to understand that test scores are only one window into the heart and soul of a person and our task is to be able to translate scores into an understanding of who this person is.

Acknowledgement

None.

Conflict of Interest

None of the authors have a conflict of interest.

References

- Wechsler D (2003) Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children (4th), San Antonio, TX: Harcourt Assessment, Inc, USA

- Wechsler D (1991) Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children (4th), San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation, USA.

- Flynn JR (1984) The mean IQ of Americans: Massive gains 1932 to 1978. Psychological Bulletin 95(1): 29-51.

- Neisser U (1997) Rising scores on intelligence tests. American Scientist 85(5): 440-447.

- Wechsler D (1946) Wechsler-Bellevue intelligence Scale, Form II. Psychological Corporation.

- Gale H Roid (2003) Stanford Binet intelligence scales. Itasca, IL: Riverside Publication.

- Raiford SE, Weiss L G, Rolfus E, Coalson D (2005) WISC-IV: Technical Report #4. Harcourt Assessment, Inc: 1-20.

- Engle RW, Laughlin JE, Tuholski SW, Conway ARA (1999) Working memory, short-term memory, and general fluid intelligence: A latent-variable approach. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General 128(3): 309-331.

- Fry AF, Hale S (1996) Processing speed, working memory, and fluid intelligence: Evidence for a developmental cascade. Psychological Science 7(4): 237-241.

- Fry AF, Hale S (2000) Relationships among processing speed, working memory, and fluid intelligence in children. Biological Psychology 54: 1-34.

- Heinz Martin S, Oberauer K, Wittmann WW, Wilhelm O, Schulze R (2002) Working-memory capacity explains reasoning ability and a little bit more. Intelligence 30: 261-288.

- Miller LT, Vernon PA (1996) Intelligence, reaction time, and working memory in 4- to 6-year-old children. Intelligence 22: 155-190.

- Vigil-Colet A, Codorniu-Raga MJ (2002) How inspection time and paper and pencil measures of processing speed are related to intelligence. Personality and Individual Differences 33: 1149-1161.

- Colom R, Rebollo I, Palacios A, Juan-Espinosa M, Kyllonen PC (2004) Working memory is (almost) perfectly predicted by g Intelligence 32: 277-296.

- Mackintosh NJ, Bennett ES (2003) The fractionation of working memory maps onto different components of intelligence. Intelligence 31: 519-531.

- Schweizer K, Moosbrugger H (2004) Attention and working memory as predictors of intelligence. Intelligence 32: 329-347.

- Opris AM, Cheie L, Trifan CM, Visu‐Petra L (2019) Internalising symptoms and verbal working memory in school‐age children: A processing efficiency analysis. International Journal of Psychology 54: 828-838.

- Garber J, Weersing VR (2010) Comorbidity of Anxiety and Depression in Youth: Implications for Treatment and Prevention. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice 17: 293-306.

- Ferrin M, Vance A (2014) Differential effects of anxiety and depressive symptoms on working memory components in children and adolescents with ADHD combined type and ADHD inattentive type. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 23(12): 1161-1173.

- Brooks B, Iverson G, Sherman ES, Roberge MC (2010) Identifying Cognitive Problems in Children and Adolescents with Depression Using Computerized Neuropsychological Testing. Applied Neuropsychology 17(1): 37-43.

- Heinz Martin S, Oberauer K, Wittmann WW, Wilhelm O, Schulze R (2004) Individuals with Disabilities Education Improvement Act of 2004, Pub L No 108-446, 118 Stat 328.

-

Stephen E Berger, Bina Parekh. Brief Case Report: Neurocognitive Assessment of a Child’s Ability to Benefit from Psychotherapy and Strategy for Court Testimony. Arch Neurol & Neurosci. 6(1): 2019. ANN.MS.ID.000627.

-

Neurocognitive, Psychotherapy, Strategy, Testimony, Psychology, psychologist, Mental Health, Emotional distress, Feelings.

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.