Research Article

Research Article

Adaptation of Mini Mental State Examination within a Population of Healthy Subjects in Mali: The Mamse

Zeïnab Koné*

Department of Neuroscience, Center Hospital-Universite du Point G, Mali

Zeïnab Koné, Department of Neuroscience, Faculty of Medicine of Pharmacy and Odontostomatology, Center Hospital-Universite du Point G, Department of Neurology Bamako, Mali.

Received Date: June 02, 2019; Published Date: July 15, 2019

Abstract

Introduction: The mini mental state is a short and comprehensive evaluation test of all cognitive functions. This is a test of 12 items with a maximum score of 30/30. However, studies have shown that it is an age-sensitive test and even more so at the level of education. In developing countries where literacy rates are the lowest in the world, the use of this tool is severely limited, hence the need to adapt this test in accordance with the socio-cultural and educational realities of each country.

Objective: This study aims to adapt the MMSE in the Malian cultural and educational context (MAMSE) to screen potentially demented subjects. Methodology: A sample of 317 subjects aged 50 and over, apparently healthy, was recruited for 9 months of investigation. These subjects were divided into a subsample of 158 literate and 159 illiterate subjects. Both groups received both tests, first the standard test and, two weeks later, the modified test. The data obtained from these different assessments were analyzed.

Results: a direct comparison of the two tests in the literate group allows to appreciate the nature of the association with the age [P- value = 0.04 (MAMSE) /0.0006 (MMSE)] and the level of education [P-value = 0.22 (MAMSE) /0.02 (MMSE)] which is less for the modified test than for the standard test. In addition, the evaluation of the illiterates found a general average of 26.79 with a general average of 27.45 for the totality of our sample.

Conclusion: These results suggest that in the socio-cultural context of Mali, MAMSE is a reliable test for detecting dementia in the elderly population.

Keywords: MMS; MAMS; Age; Education; Dementia; Adaptation

Introduction

With the improvement of living standards, we are witnessing a rise in life expectancy, with an increase in the elderly population [1]. In both the developing world and the developing world, dementia, a condition particularly affecting the elderly, has increased in population [2,3,4]. Indeed, in 2005, it was estimated that 24.3 million people had dementia worldwide, with 4.6 million new cases per year or one case every 7 seconds. This number is estimated at 42 million for 2020 and 81.1 million for 2040 [5]. An extrapolation of these figures finds for: Africa 3.5 million people reached in 2005 and 6.5 million in 2020; for Mali, 49200 in 2005 and 92000 in 2020. With such substantial numbers, the screening of potentially demented subjects becomes a necessity through the use of an efficient diagnostic tool. The developing countries that we represent must anticipate the very great impact that these pathologies will have on our elderly populations in the years to come. The identification of potentially demented populations is a necessity and this requires the use of a reliable screening tool. Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) [6] is a screening test to evaluate overall and brief cognitive functions (temporospacial orientation, memory, attention, language skills and visio-spatial capabilities).

It is a test of 12 items with a maximum score of 30/30. For a better understanding of this instrument, the work of Tombaugh and McIntyre (USA), (1995) [7] concluded the reliability of its tested parameters. Very early, studies found that age and socioeducational level had a strongly significant association with MMSE performance. Studies by Brayne and Calloway (USA) (1990) and Bravo and Hebert in USA (1997) have demonstrated a link between age, education level and MMSE performance [8-10]. The MMSE presents several items requiring literacy skills, and it has been shown that this test is more strongly influenced by the level of education [11]. Thus, it becomes easier to understand how difficult it is for people in developing countries, most of whom are illiterate, especially in their older age group, to receive this test in order to detect a dementia syndrome [12].

In an effort to address this need for screening of the elderly population in developing countries, researchers have attempted to modify the MMSE so that it can be administered to illiterate populations. The first tests, like the Chinese version, which had brought a slight cultural change in addition to a transcription of the original instrument was not very conclusive. Studies have shown that it is accessible only to people who have received a minimum of literacy [13]. Another version, this time Korean, has proved a certain relationship with the level of literacy without much satisfaction [14]. In addition, substantial changes in the Nigerian version have shown a lesser association with the level of education than for the MMSE [11]. Finally, an Indian version [15] that tried to take into account both cultural and educational aspects, showed a weak association with the level of education. Although this version showed a correlation with the level of education.

Even though these results were encouraging, no study compared the performance of a modified version with that of the standard tool in a single sample before the Bangladesh version, which seems to us to be the adaptation model that offers the most of satisfaction [16]. The present study proposes to adapt a Malian version of the MMSE, with a view to its use in the socio-cultural context of Mali.

Materials and Methods

Population

These are adult subjects, aged 50 and over, male and female residents living in the study area and at the time of study. All individuals were classified into two literacy groups (subjects with at least seventh grade education) and illiterate (subjects who dropped out of school before completing the basic education certificate).

Sampling

The sampling technique was random and based on the areolar method. The subjects were recruited in town or in their homes (door to door) in the geographical area of commune 4. Starting from the road along the river, we entered each adjacent lane to retain all seventh concessions located on the right side of the alley. Thus, during the operation, we moved into concessions where there were zero eligible candidates and others who had more than one. However, the majority of the subjects who were absent for our first visit presented themselves at the time of the appointment for the second round of the first evaluated. This sampling technique allowed us to recruit 317 subjects in the said common, distributed in 158 s literate and 159 illiterate. The sample size was not calculated beforehand. The investigation concerned any subject of fifty years or more, well free from all affections potentially altering memory.

Interviews

The data were collected by a set of four interviewers with an average level of baccalaureate plus two years, who received training in the way of passing the tests and supervised by a student at the end of the cycle of medicine. The interviewers went to meet the subjects and questioned them with both instruments. Before going into the actual interview, the interviewers were required to approach the topics as respectfully as possible, to explain to them the purpose and content of the tests. Interrogation often took place in the presence of other people (it was the parents of the participant, who did not see any objection). The data was thus collected for each individual.

Material

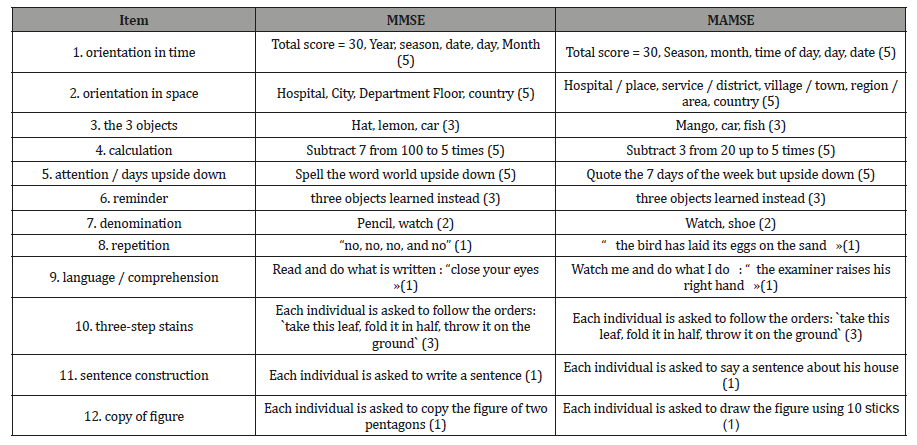

At the time of administering the test, the examiner had a watch, a pair of shoes, 10 sticks, a sheet of paper, and a model of the figure to be reproduced. The original English version of the MMSE has been replaced by the French GRECO version of the MMSE. For the MAMSE, some MMSE items have been modified (ref.1) to respond to the socio-cultural context of Mali (Table 1).

Proceedings

Both tests, MMSE and MAMSE, were first tested on students from the Faculty of Medicine and Ophthalmology to familiarize interviewers with test administration.

Adaptation: We operated on changes consistent with the Malian sociocultural context while reaching the desired cognitive domain. The use of a model for potentially illiterate populations, developed by the specialists of the memory center of Lille (France) contributed to the choice of items. So the following changes have been made: (Table 1)

Table 1: Descriptive item comparison for both instruments (numbers in parentheses indicate the high score of the item).

a. Temporal (/5pts) and spatial (/5pts) orientation: Accept only the correct answer. However, when changing seasons or months, allow the patient to correct a wrong answer by asking,”Are you sure?”. If the subject gives two answers or a vague answer, ask him /her to specify and take into account only the definitive answer. Each correct answer is worth (1) point. Allow about 10 seconds for each answer.

b. Repetition of the three words (/3pts): Instructions:”Now we will go to the memory, I will give you three words; you will repeat them after me, and I will ask them again later. It is. Make sure the patient understands the task and then read the three grouped words, at a rate of 1 per second, facing the patient, articulating well. Allow 20 seconds for the answer. Give 1 point for each correct answer. If the patient does not reproduce the three words correctly on the first attempt, repeat them (all three, even if only one is omitted) up to five times, or until all the words are learned. Note that the quotation is based only on the first repetition of the words. Oral calculation (/5pts):” A man with 20 francs to take the bus. Every day, he spends 3f to pay for his bus. Once the first day is over, he will have 17 francs left. How much will he have the next day and the next,...”We stop the patient after five subtractions. The patient must calculate alone and perform the successive subtractions. Each correct subtraction is entitled to one point. If the patient is wrong, it is not corrected and the point is not attributed. If the following subtraction, from the wrong result, is correct, the patient receives 1 point. If the patient asks during the task,” How much to remove? It is not allowed to repeat the instruction (“continue as before”). If it seems nevertheless essential to give the instructions, we must start from the initial instruction (“ A man at 20 francs to take the bus.” Every day, he spends 3f to pay his bus.Once the first day, he will it remain 17 francs How much will it remain the following day and the next,...”). And resume the test at the beginning. Then assign the points. Always do the following test (“ Name the days of the week in reverse, that is starting from the last and then naming the day before, so before Sunday comes Saturday and before Saturday comes...?”). The points of this event are not counted in the final score (the purpose of this test is only to propose an interfering task before the recall of the three words). If the patient has significant difficulty in performing this test, ask the subject to quote the days of the week in the conventional sense.

c. Memory (/3pts): The word recall order plays no role, telling the subject that he must give back the three words given previously (“ Do you remember the three words I gave you earlier?”). Allow 10 seconds. No tolerance is allowed since the encoding was checked during the recording. Do not give clues.

d. Denomination (/2pts): Show the patient successively a watch and shoes asking each time” What is it?”. Give one point for each correct denomination and give 10 seconds for each answer. The answers allowed are” watch” or” wristwatch », And« shoes”. The subject must not take the objects.

e. Repetition (/1pt): Repeat after me: The bird has laid its eggs on the sand”. The sentence must be read aloud, slowly, very distinctly, with intonation and in front of the patient. Give a point if the repetition is the same in every way. If the patient says not to have heard, not to repeat the sentence (if there is any doubt about the quality of the patient’s hearing, it will be possible to verify by representing him the sentence at the end of the examination).

f. Complex order (/3pts): Put a sheet of paper on the table and give the order in one go (“ Take the paper with your right hand, fold it in half, throw it on the floor.”), Taking care not to ask the leaf on the right side of the patient. Each successful manipulation is entitled to 1 point (maximum score = 3). If the subject stops and asks what to do, do not repeat the instruction, but say” Do what I told you to do”.

g. Verbal order (/1pt): Do like me”, the examiner must raise his right hand. The correct execution (raising the right or left hand) gives 1point right.

h. Construction of a sentence (/1pt): Ask the patient to verbally construct a sentence about his house” Tell me something about your house”. The sentence must include at least one subject and one verb.Syntax errors are not taken into account.

i. Copy of the drawing (/1pts): Present the model to the patient, give him 10 sticks and ask him:” Reform this drawing with the sticks”. Several tests can be allowed and a time of one minute allowed. In order to obtain a point, the patient must reproduce the 10 angles and the 2 corners must intersect on 2 different sides. A rotation of the figure is not penalized. The maximum score on this scale is 30 points.

Reliability of parameters: It is a question of describing a number of variables to see if they have the same properties when comparing the two tests. Variables tested are age level of education, level of onset of hardship, and statistically significant association.

Best performance of MAMS: We wanted to establish the proof of a better performance of the modified tool in our context with its peculiarities first of all by comparing the results of each test in the group of literati then, to look for criteria of satisfaction of the evaluation of the illiterate to finally appreciate the results of our entire sample.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the SAS version 9.1 software. A value ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant. A chi-square test was used to compare proportions and evaluate associations betweenvariables. To explore the data, we used univariant analysis in determining the distribution frequencies of the variables. Covariants included are the age of the patient, his level of study, and the different items of the MMSE. The student-t test was used to compare the averages of the continuous variables.

Results

Reliability of parameters

These results relate exclusively to the sub-sample of the literate

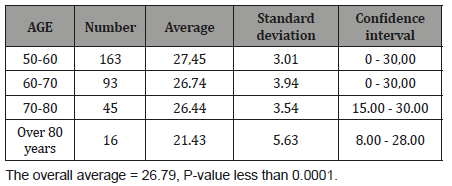

• The age

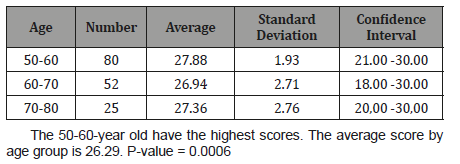

a) MMS: (Table 2)

Table 2: Descriptive item comparison for both instruments (numbers in parentheses indicate the high score of the item).

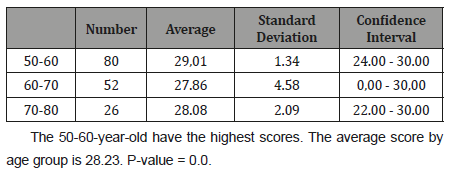

b) MAMS: (Table 3)

Table 3: Mean age for MAMS.

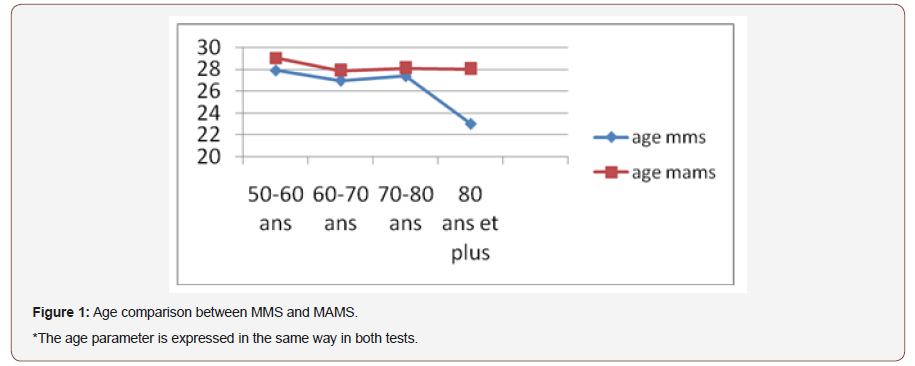

c) MMS compared to MAMS in relation to the variable” age”: (Figure 1)

The age parameter is expressed in the same way in both tests.

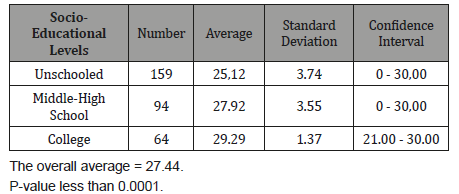

• The level of education

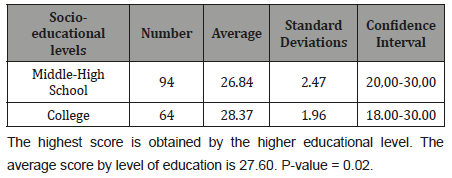

a) MMS: (Table 4)

Table 4: Average per level of education for MMS.

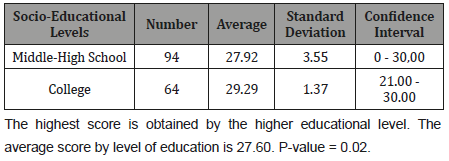

b) MAMS: (Table 5)

Table 5: Average per level of education for MMS.

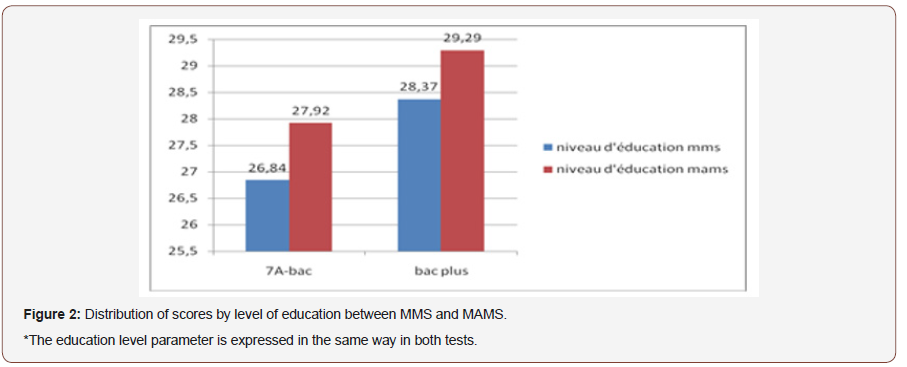

c) Comparison between MMS and MAMS in relation to level of education (Figure 2)

The education level parameter is expressed in the same way in both tests.

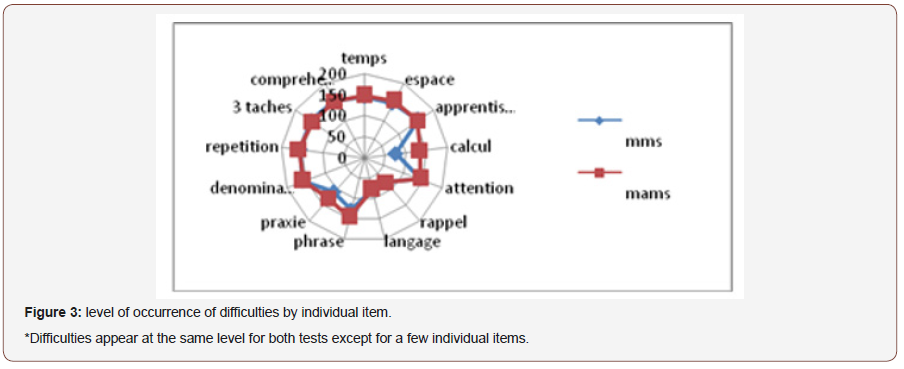

• The level of occurrence of difficulties: (Figure 3)

Difficulties appear at the same level for both tests except for a few individual items.

Associations between the two instruments: (Table 4)

Best performance of MAMS

• The subsample of the literati:

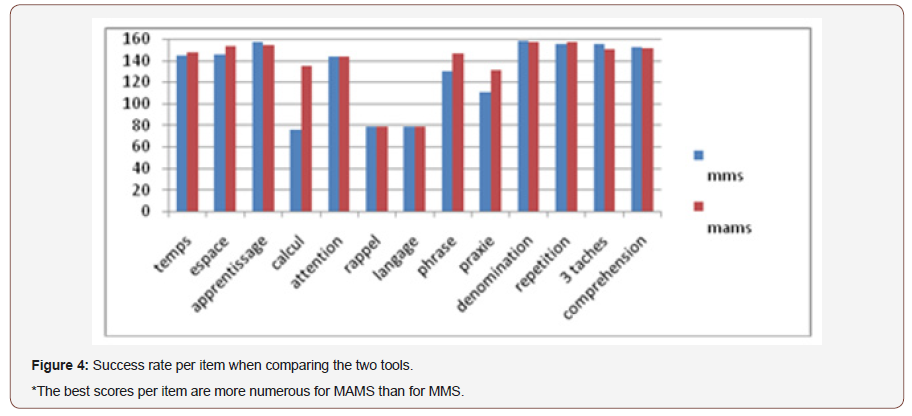

a. Success rate for different items: The best scores per item are more numerous for MAMS than for MMS (Figure 4).

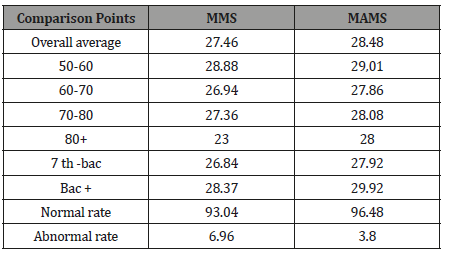

b. Success rate according to the different parameters of the two tests. Compared to the different points of comparison, the MAMS is more efficient than the MMS (Table 5).

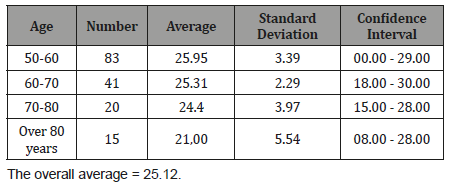

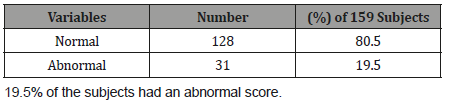

The sub-sample of illiterates:(Table 6 & Table 7)

Table 6: Descriptive item comparison for both instruments (numbers in parentheses indicate the high score of the item).

Table 7 Descriptive item comparison for both instruments (numbers in parentheses indicate the high score of the item).

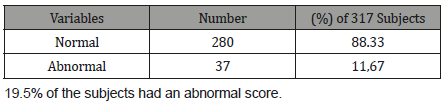

The totality of our sample: (Table 8 ,Table 9, Table 10, Table 11 and Table 12)

Table 8: Descriptive item comparison for both instruments (numbers in parentheses indicate the high score of the item).

Table 9: Descriptive item comparison for both instruments (numbers in parentheses indicate the high score of the item).

Table 10: Descriptive item comparison for both instruments (numbers in parentheses indicate the high score of the item).

Table 11: Descriptive item comparison for both instruments (numbers in parentheses indicate the high score of the item).

Table 12: Descriptive item comparison for both instruments (numbers in parentheses indicate the high score of the item).

Comments and Discussions

The main objective of this study was to adapt and validate a Malian version of MMS (MAMS) that can be used by the illiterate Malian population. To do this we compared the two instruments first, in a sample of literates to test the parameters of the modified instrument. And secondarily we appreciated the performance of the modification by using it on illiterate elderly people. So the results obtained allowed us to make the following deductions.

The adaptation

At this level, our approach was not only to make changes to the items requiring literacy skills in accordance with Malian sociocultural and educational contexts, but above all to ensure that these changes reached the desired cognitive domain. This adaptation procedure has been applied by other works (India, Nigeria, Bangladesh) [6-8]. In the first Korean and Chinese versions, the level of education was not taken into account, which is a weakness in terms of the efficiency of these tools [9,10].

The reliability of the various parameters of MAMS

The different parameters (general average, score by items, level of onset of difficulty by individual item, and sensitivities at age and education level) tested from MAMS showed the same properties as those of MMS. This is verified by the comparison between the average scores of the two tests in the subsample of the literati:

Level of occurrence of difficulties per individual item:The direct comparison edits us on the level of occurrence of difficulties that is similar in both tests. This concordance was found by Ganguli et al (India) in 1995 [16]. This aspect is clearly shown in Figure 4 which shows how the respective curves of the two functions (MMS /MAMS) have similarities in their respective scalutivities.

The level of education and age: A direct comparison of the two instruments used to assess the nature of the associations with age and level of education in the subsample of scholars that is similar in both tests. These shades are better captured by the representations of Figures 1 and 2. The analysis of these parameters makes it possible to affirm that there is a positive association with the level of education (the better the subject is educated is his score) and a negative association with age (the older the subject is less good is his score). And these two parameters have this identical expression for both tests. These results are identical to those of Brayne and Calloway (USA), (1990) and those of Bravo and Hebert (USA), (1997) who found the same associations positive with the level of education and negative with age [3,4].

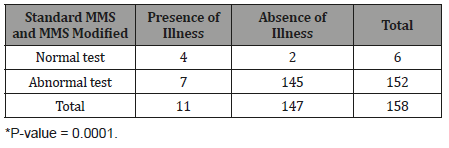

Association: There is a strong, statistically significant association between the two instruments when compared (P = 0.0001). These results are consistent with those of the Chinese version e (P≤ = 0.05) [17-18].

The best performance of MAMS:

The subsample of the literati: In this sub-sample, compared to MMS, MAMS is more efficient with a higher overall average, a lower association with the education level, and at the same discriminatory threshold (24), a lower abnormal rate of return. (6) only for the MMSE (11). This last point is comparable to the first Nigerian works on the subject which discussed the rarity of dementia among blacks [19]. The lower sensitivity of MAMS to the level of education is so remarkable that this sensitivity completely disappears with a mean level of the 7th year with a P-value = 0.22. Age sensitivity, although low for both instruments, is lower for MAMS (P-value = 0.04) than for MMS (P value = 0.0006).

Under sample of illiterates: In the standard version, the test was not accessible to out-of-school people. The first of the remarks to make is the accessibility of the modified version to any type of population because the items involving capacities of literate people have been modified so that they do not constitute any more obstacles to the evaluation of the cognitive functions of these populations. One of the major handicaps of this instrument, modified or not, is its sensitivity to age but especially to the level of education. It appears that the Malian version has been able to make modifications adapted so that this sensitivity is the finest possible. As the results show, despite their illiteracy; this subsample managed to have a general average above 24, an average of 25.12. This average seems perfectly appropriate, because the level of education is extremely considerable, in other contexts, in a highly educated person, an average of 28 may be abnormal if it all relates to the recall event.

All of our sample literate and illiterate:

The statistical analysis of the properties of the various parameters of the modified tool shows a satisfaction in the results obtained: A general average above the discriminating threshold is a general average of 27.44.This best performance may have several reasons among which we propose to discuss the most likely:

• In terms of the item evaluating the orientation in time, the sub-item * year * was replaced by the sub-item * time of day * because for the majority of the Malian population who was not at the school, the years are identified in relation to the major events that took place during the latter rather than any reference to the calendar. The ranking order of the sub items (season, month, time of day, day and date) corresponded more to the profile of our population. These two reasons seem to me the most likely to explain the larger score of the MAMSE than the MMSE in this item.

• In terms of the item assessing the orientation in space, the modifications made to correct the difficulties of the population as to their way of finding oneself which does not correspond at all to a geographical division according to the Western model which is unknown to many of our older subjects which refers rather to a local model.

• At the level of calculation, placing the operation in a context of their daily life aroused the interest of the subjects, who thus gave their attention to the question with a sufficient concentration, that the abstract operation proposed by the original test.

• The high score in the recall and naming tests is probably due to the use of the words commonly used in the everyday life of the population as the words used in the original test and therefore easier to remember. In any case, the choice of words coming directly from the local vocabulary also contributed to raising the score. The fact also to choose sub items of the same semantic nature (here names) favors the memorization and at the same time raises the score to the recall.

• At the level of the item of repetition, the choice of a sentence belonging to the local vocabulary greatly facilitated this repetition.

• In terms of the sentence construction and figure copy items, the changes made these tests of the schooling skills required by the original test, in addition to the embarrassment of the original version in making blunders in front of students (spectators).

Conclusion

The elderly population is now a very important part of the medical consultation. The proper management of their health problems is a necessity that requires a better understanding of the phenomena surrounding old age. In the case of dementia, the first is the use of a reliable tool leading to diagnosis. The qualities of a tool like the MMS, which has been proven all over the world, motivated our choice to adapt it to our socio-educational context. The comparison of the MAMS parameters with those of the MMS allowed us to say that the two tools have the same properties. The intrinsic characteristics of the modified test (MAMS) are those of a good screening test. And in the end, the best performances are those of the evaluation with the MAMS.

Thus, in the light of the results and discussions of this study, it appears that MAMS can be considered as a reliable and valid instrument for a cognitive assessment of the populations in Mali. In conducting this study, it was proposed to provide the Malian practitioner with a cognitive assessment instrument adapted to the socio-cultural context of the Malian populations, and our results suggest that this objective is achieved.

Acknowledgement

None.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest.

References

- Levkoff SE, Maxarthur IW, J Bucknall (1995) Eldery mental health in the world development. Soc Sci Med 41: 983-1003.

- Liu HC, KN Neck, Wang SJ, Fuh JL, HC Lin, et al. (1994) Assessing cognitive abilities and dementia in a predominantly illiterate population of older individuals in Kinsmen. Psychol Med 24: 763-770.

- T eng El, Hasegawa K, Homma A, Imai Y, Larson E, et al. (1994) The cognitive capacity screening instrument (CASI): a pratical test for cross cultural epidemiological studies of dementia. Int J psucho-Geriatr 6: 42- 58.

- Fratiglioni L, Viitanen M, von Stauss E, Tontodonati V, Herlitz A, et al. (1997) Vrey old women at highest risk of dementia and Alzheimer’s diseases: incidence data from the Kingsholmen Project, Stockhom. Neurology 48: 132-138.

- Kawas CIL, Corrada M (2006) Alzheimer’s and dementia in the oldest-ol: a century of challenges. Curr Alzheimer Ress 3 (5): 411-419.

- Hendrie DC, Murell J, Gao S, FW Unversagt, Ogunniyi A, et al. (2006) International studies in dementia with particular emphasis on populations of African orogin. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord (3 suppl2): S42-S46.

- MF Folstein, Folstein SE, Mchugh PR (1975) “Mini Mental State”: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J psychiatric Res 12: 189-198.

- Tombaught TN, McIntyre NJ (1992) The Mini Mental State Examination: a comprehensive review. JAGS 40: 922-935.

- Brayne C, Calloway P (1990) The association of education and socioeconomic status with the Mini Mental State Examination and the clinical diagnosis of dementia in elderly people. Age Aging 19: 91-96.

- Bravo G, Hebert R (1997) Age- and education- specific reference values for the Mini Mental and Modified Mini Mental State Examination derived from a non-demented elderly population. Int J Geriatr Psychiat 12: 1008-1018.

- Laurner LJ, Dinkgreve MAHM, Jonker C, Hooijer C, Lindeboom J (1993) Are age and education independent correlates of the Mini Mental State Exam? J Gerontol Psychol Sci 48: P271-277.

- Weiss BD, Reed R, Kligman EW, Abyad A (1995) Literacy and performance on the Mini Mental State Examination. JAGS 43: 807-810.

- Baiywu O, Bella AF, Jegede RO (1993) The effect of demographic and health variables on a modified form of Mini Mental State Examination scores in Nigerian elderly community residents. Int Geriatr Psychiat 8: 503-510.

- Katzman R, Zhang M, Ya-Qu O, Wang Z, Liu WT, et al. (1988) Chinese version of Mini Mental State Examination: the impact of illiteracy in Shanghai Dementia Survey. J Clin Epidemiol 41: 971-978.

- Park JH, Kwon YC (1990) Modification of the Mini mental State Examination for use in the elderly in a non-western society. Part 1. Development of Korean version of Mini Mental State Examination. Int J Geriatr. Psychiat 5: 354-359.

- Ganguli M, Ratcliff G, Chandra V, S sharma, Gilby J, et al. (1997) The Hindi version of the MMSE: the development of the cognitive screening instrument for the illiterate rural population in India. Int J Geriatr Psychiatr 10: 367-377.

- Kabir ZN, Herlitz A (2000) The Bangla adaptation of the Mini-Mental State Examination (BAMSE): an instrument to assess cognitive function in illiterate and literate individuals. Int J Geriatr Psychiatr 15 (5): 441- 450.

- Xu G, Meyers JS, Huang Y, Du F, Chiwdhury M, et al. (2003) Adapting mini-mental state of xamination for dementia screening among illiterate or minimally educated elderly Chinese. Int J Geriatr Psychiatr 18 (7): 609-616.

- Tiwari SC, Tripathi RK, Kumar A (2009) Applicability of the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) and the Hindi Mental State Examination (HMSE) to the urban elderly in India: a pilot study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatr 21(1): 123-128.

- Osuntokun BO, Adeuja AOG, Shomberg BS, Bademosi O, Nottidje VA, et al. (1987) Neurological Disorders in Nigerian Africans: A Community- Based Study. Acta Neural Scand 75: 13-21.

-

Zeïnab Koné. Adaptation of Mini Mental State Examination within a Population of Healthy Subjects in Mali: The Mamse Arch Neurol & Neurosci. 4(2): 2019. ANN.MS.ID.000584.

-

Mini Mental State, Population of Health, Neuroscience, MMS; MAMS; Age; Education; Dementia; Adaptation

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.