Research Article

Research Article

Demographics, Treatment Characteristics, and Bio-Psycho-Social Burden of Patients with Migraine Seeking Help from Pain Specialists in Germany-Results of a Cross-Sectional Analysis of Depersonalized Data Provided by the German Pain E-Registry

Michael A. Überall1*, Heinrich Binsfeld2, Dorothea Fago3, Thorsten Lücke4, Silvia Maurer5, Norbert Schürmann6 and Johannes Horlemann6

1Private Institute of Neurological Sciences – IFNAP, Center of Excellence in Health Care Research, Nordostpark 51 90411 Nürnberg, Germany

2Regional Pain Center Ahlen, Kirchplatz 7 48317 Drensteinfurt, Germany

3Regional Pain Center Gießen/Pohlheim, Neue Mitte 12 35415 Pohlheim, Germany

4Regional Pain Center Linz, Magdalena-Daemen-Str. 20 53545 Linz am Rhein, Germany

5Regional Pain Center Moers, Asberger Str. 4 47441 Moers, Germany

6Regional Pain Center Kevelaer, Grünstrasse 25 47625 Kevelaer, Germany

Michael A Überall, MD/PhD, Private Institute of Neurological Sciences – IFNAP, Center of Excellence in Health Care Research, Germany.

Received Date:August 05,2024; Published Date:August 26, 2024

Abstract

Background

Headache is a common complaint across all age groups and migraine its second most common cause, with a global prevalence of 14.7%. Migraine is one of the prominent causes of chronic suffering and disability. Due to their recurrent course and often unpredictable attacks, migraines not only affect the normal course of the day, but also develop the potential for psychological changes in the sense of post-traumatic stress disorders. Although highly effective diagnostic tools and specific acute and prophylactic treatments exist, a significant proportion of patients is neither adequately treated nor their disease-related burden specifically realized. The aim of this study was to evaluate the bio-psycho-social burden in migraine patients who reported on their headaches to the German Pain e-Registry visiting a specialized pain medicine facility in Germany.

Methods

Exploratory, cross-sectional single-cohort analysis of patients with migraine based on depersonalized routine data of the German Pain e-Registry (GPeR).

Results

Overall, 15,919 patients (83.8% female; age 41.3±10.6 years) of the GPeR with migraine (33.0% with aura) were identified to suffer since 12.4±6.0 years. Monthly headache/migraine/migraine-related sick leave days were 12.5±6.7/10.5±5.8/8.8±4.9 on average, 52.2% suffered from high frequency episodic, 16.0% from chronic migraine. Monthly migraine days with acute medication were 10.4±5.5 and 82.3%/87.5% reported the use of migraine-specific/non-specific acute medication on a regular basis. Guideline recommended conventional/other/CGRP-based prophylactics were taken by 34.2/23.8/9.1%, nonpharmacological prophylactic measures by 99.3%. The modified pain disability score was 43.3±17.7 (34.2% >50) mm VAS, physical/mental quality-of-life was 41.0±8.0/45.2±12.4, 53.3/51.1/39.4% documented moderate to extreme depression/anxiety/ stress scores, and 53.2% a significantly impaired overall wellbeing. Suicidal ideation was frequent and noted “sometimes” by 25.6% and “more frequent” respective “more concrete” by 10.4%.

Conclusion

Migraine is a common chronic pain condition. Recurrent episodic headache attacks severely impair quality of life and participation in daily life activities of those affected who are in need prophylactic countermeasures. Despite the existence of newer prophylactic agents (e.g. CGRP-mAB) and clear guideline recommendations, the majority of those in need weren´t treated adequately.

Keywords:Headache; migraine; Bio-psycho-social burden; Quality-of-life; Depression; Anxiety; stress; German Pain e-Registry

Background

Headache is a common complaint across all age groups. Recurrent headaches cause a considerable burden on the individual as well as the society. The second most common cause of headache is migraine [1], which can occur at any age but frequently begins during puberty. It is most prevalent in individuals aged 25–55 years which is considered as the most productive years in the life of a person. Among this population migraine is one of the prominent causes of chronic suffering and disability [2,3]. Phenomenological, migraine – a so called primary headache disorder in which headaches itself are the main problem and not secondary symptom of an underlying disease or condition [4] – is an attack-like headache that recurs at irregular intervals. Some people only have a migraine once or twice a year. Others suffer from migraines several times a month or even almost daily. The headache is pulsating, throbbing, or stabbing. It often occurs on one side of the head but can either spread to the other side or switch its manifestation side between attacks. Migraine attacks last from a few hours to three days, however, in children and older people the attacks are often shorter. The pain is usually accompanied by vegetative symptoms such as loss of appetite, nausea, and photophobia as well as hypersensitivity to noise and smells. Physical exercise usually exacerbates the pain and accompanying symptoms. Many patients have to interrupt their normal daily routine, take medication, and go to bed because of their headaches [5]. Migraines are one of the most common neurological disorders. Around 12 to 14% of all women and 6 to 8% of all men suffer from migraines [6,7]. In young children and schoolchildren up to puberty, 4 to 5% are affected [8]. Most women suffer their first migraine attack between the ages of 12 and 16 years, men a little later at the age of 16 to 20 years. Migraines peak in frequency and severity between the ages of 30 and 40 and slowly subside from the age of 55 [9]. Various research works report that migraineurs experience a lower quality of life than other patients who suffer from chronic problems like depression, hypertension, and diabetes [10]. Migraine headaches results in significant impairments in physical, social, and mental domains of health, and affects various dimensions of life such as physical, vocational, academic, social, financial, and family [11-14].

Study Objective

This article summarizes the results of a health care research project performed to evaluate demographics, treatment characteristics, and the biopsychosocial profile of patients with migraine who consulted a specialized pain center in Germany. Rationale for that approach was the observation that a significant proportion of patients affected by migraine still find it very difficult to adequately express the considerable extent to which they are physically, mentally, and emotionally affected or to be sufficiently recognized regarding their individual impairments. For this reason, the German Pain Association has launched and financed the subsequent healthcare research project entitled “BIOMIG” in 2022 to gain deeper insights into the biopsychosocial profile of migraine patients seeking specialized medical care based on primary data from daily routine care procedures provided by the German Pain e-Registry (GPeR).

Patients and Methods

Evaluation concept

Methodologically, this evaluations formally followed the concept of a non-interventional, retrospective cohort study with a onetime cross-sectional analysis of completely depersonalized data of patients with migraine which were recorded for the first time within a prespecified evaluation window (January 2nd, 2015, to June 30, 2022) using the standardized procedures and validated self-reporting instruments of the German Pain Questionnaire according to the quality agreement for special pain therapy defined in section 135 (2) of the German Social Security Code V).

Patients

There was no formal sample size calculation for this analysis. Data sets of adult patients with migraine were selected for the purpose of this study, mirrored/extracted in depersonalized form, and analyzed as specified in the corresponding statistical analysis plan. Patients were identified with reference to the medical ICD-10 diagnosis code G43 with the subcategories G43.0 (migraine without aura) and G43.1 (migraine with aura). Additional categorizations of the migraine disorder were made with reference to specific details/ information in the documentation. The evaluation was carried out retrospectively, exclusively using the data already available at the time of the cut-off date and after complete anonymization with regard to patient and institution or treating physician. In addition, the results of the evaluations were provided exclusively in the form of aggregated tables, which do not allow any conclusions to be drawn about the response of individual patients.

Data documentation

All data used for this analysis was originally routinely documented/ recorded using electronic end devices (tablets, smart phones or desktop computers) and the online documentation platform iDocLive® provided by O. Meany-MDPM GmbH as part of standard care and primarily for the purpose to improve individual patient care. At no time during these documentations was there any intervention or financial compensation in the sense of an expense allowance for any additional documentation costs associated with the use of iDocLive® or for the prescription of specific therapies. The majority of the data reported to/stored in the German Pain e-Registry and thus available in depersonalized form for health services research was documented directly by patients using validated self-reporting instruments recommended by the German Pain Association (Germanys largest pain specialist organization), the German Pain League (Europe’s largest umbrella organization for patients with chronic pain), and the German chapter of the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP), the German Pain Society. The data collection using the online documentation platform iDocLive® enables a comprehensive non-selective mapping of the patient structure treated in the participating pain practices/ centers. Use of the electronic documentation platform iDocLive® was/is free of charge for members of the German Pain Association and patients, regardless of their insurance status.

Parameters of the German Pain e-Registry

The core parameters of the German Pain e-Registry based on the contents of the German Pain Questionnaire and the German Pain Diary (in the form agreed by the German Pain Association and the German Pain League) [15]. and include information on the patient’s age, gender, height, body weight and body mass index (BMI), pain duration and age at first onset of migraine symptoms, pain intensity grading according to von Korff [16], treatment approaches, pain intensity (lowest, average and highest 24-hour pain intensity), individual treatment goals and the so-called pain index (i.e. the arithmetic mean of the 24-hour pain intensity data; all assessed via a 100 mm visual analogue scale [VAS] with the endpoints 0 = no pain, 100 = worst pain imaginable), the extent of pain-related impairment of activities of daily living (using the modified Pain Disability Index, mPDI, assessed with the VAS comparable to the pain intensities) [17], the general and pain-related quality of life using the short form of the VR-36 Health Survey (VR-12) [18, 19] and its physical/mental component subscales (PCS/MCS), depression, anxiety and stress (assessed via the Depression, Anxiety-Stress Scale, DASS-21) [20,21], migraine-related disability (via the MIDAS questionnaire) [22] comorbidities, and concomitant therapies, etc. With reference to the standardized scaled values for a) pain index (PIX), b) highest 24-hr. pain intensity (HPI), c) modified Pain Disability Index (mPDI), d) pain-related impairments in personal care and activities of daily living (mPDI-5), e) physical and f) mental quality of life (VR12-PCS/MCS), g) depression (DASS-D), h) Anxiety (DASS-A), i) stress (DASS-S) and j) suicidal ideations, a “Burden of Pain” (BoP) Index was calculated (with a possible range of values for the pain-related burden of those affected between 0=no burden and 100=maximum possible burden) specifically for the purpose of this study.

Data analysis

In accordance with the design of this non-interventional study, available data was analyzed retrospectively using explorative procedures and suitable descriptive statistical methods. The number of available or unavailable values (non-missing or missing data) was specified for all variables, irrespective of the data level. For nominally and ordinally scaled categorical data, the absolute and relative (possibly adjusted) frequencies were also calculated and cumulative values for ascending/descending scale levels were presented. Interval-scaled data were presented by specifying the mean, standard deviation, median, range (minimum - maximum) and 95% confidence interval and - where possible and appropriate - additionally grouped categorically with regard to defined cut-off values and provided with corresponding frequency analyses. All data were analyzed as reported, i.e. missing values were neither replaced nor imputed. The optional use of biometric test procedures to compare the values between different sub-cohorts was used exclusively for post-hoc assessments of the biometric significance of observed differences in frequency or expression and explicitly not for testing predefined questions and/or hypotheses. All tests used were evaluated with reference to a statistical significance level of 5% and the test procedures used were adapted to the scale level of the variables to be analyzed.

Ethics

The exclusive use of completely depersonalized data (with regard to the practitioner and data subject) and the written informed consent of all participants to the use of their anonymized data for scientific health care research projects ensured compliance with the requirements of the EU General Data Protection Regulation and national aspects of patient (data) safety. The study concept and statistical analysis plan were assessed and approved by the Executive Board of the German Pain Association. Aspects of data protection and patient safety were reviewed by the Executive Board of the German Pain League and independent data protection officers. The present work was implemented under the guidance of the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Study Registration

Prior data extraction and analysis, this study was entered in the online register of the European Medicines Agency (EMA) for non-interventional studies (ENCEPP; EU PAS Identifier: 50135) and thus made public.

Results

Population

Based on the existing data set of the German Pain e-Registry as of June 30, 2022, a total of 15,919 patients with a diagnosis of migraine were identified for this analysis using the definitions and criteria specified in the statistical analysis plan and their anonymized data were used as the basis for the present evaluation.

Demographic Characteristics

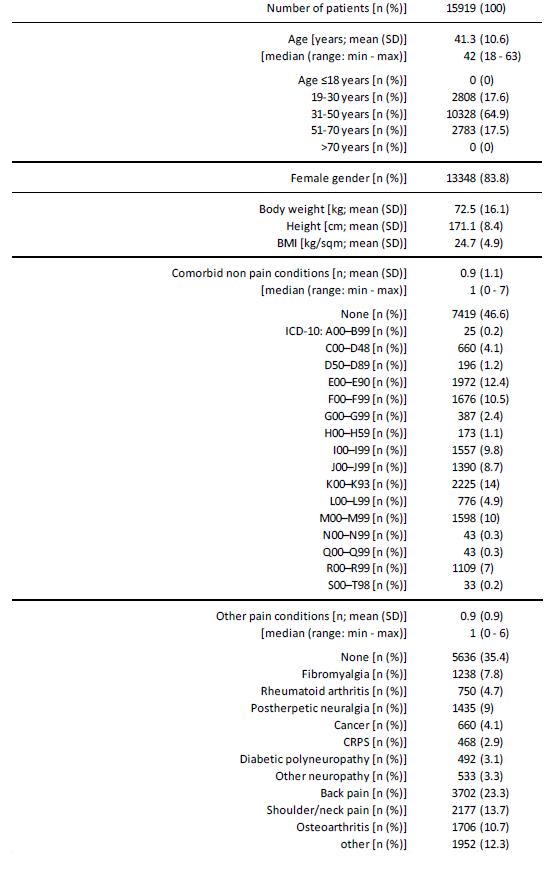

With a range between 18 and 63 years, the mean age of the evaluated patients was 41.3±10.6 (median 42) years. 2,808 patients (17.6%) were 30 years or younger at the time of the evaluation. 2.783 patients (17.5%) were over 50 and 632 (4.0%) over 60 years (Table 1). With a total of 5,866 patients (36.8%), the largest age group in terms of numbers was between 41 and 50 years of age. According to the known data from the literature, the majority of patients identified with a diagnosis of migraine were female at 83.8% (n=13,348). Comorbid conditions were prevalent in this population (on average 0.9±1.1, median 1, range: 0-7) and affected more than half of patients (53.4%). 10,283 patients (64.6%) also reported other concurrent pain conditions, most prevalently those affecting the musculoskeletal system (e.g. back pain in 23.3% shoulder neck pain in 13.7%, and osteoarthritis in 10.7%).

Migraine Characteristics

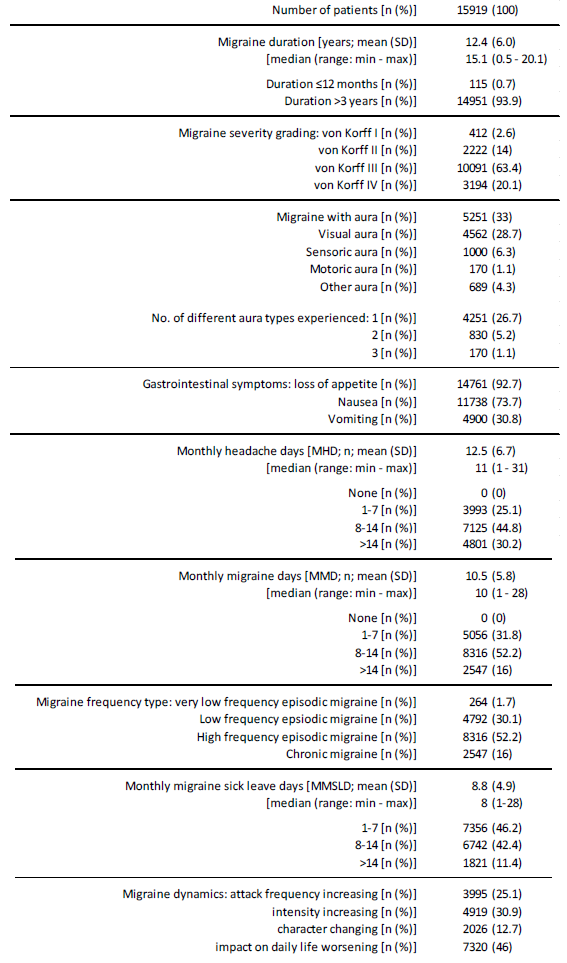

With 93.9%, more than nine out of ten patients (n=14,951) documented a pain duration of more than three years (Table 2), 5.4% (n=853) a duration of 1-3 years and 0.7% (n=115) of 7-12 months. With reference to the available time data, a mean duration of illness of 4,524.0±2,185.8 (median 5,507, range 186 - 7,331) days could be calculated, corresponding to 12.4±6.0 (median 15.1; range 0.5-20.1) years. Referenced to the von Korff pain grading system, 10,091 patients (63.4%) were classified as grade III and further 3,194 /20.1%) as grade IV indicating the existence of a chronic pain disorder characterized by the experience of high pain intensities with moderate (grade III) to severe (grade IV) disability. 5,251 patients (33.0%) documented the presence of a so-called “classic migraine” with aura. The most frequently documented form of aura were visual auras, reported by 4,562 (28.7%) of patients, followed by sensory auras (n=1,000; 6.3%), other auras (n=689, 4.3%) and motor auras (n=170, 1.1%). Most patients (n=4,251, 26.7%) documented the manifestation of a single aura form for their respective case, but 830 patients (5.2%) reported experiences with two different auras and as many as 170 patients (1.1%) reported their experiences with three different aura forms. Gastrointestinal symptoms accompanying their migraine attacks were reported by roughly nine out of ten patients (n=14,761, 92.7%), most frequently loss of appetite (n=14,761, 92.7%), nausea (n=11,738, 73.7%) and vomiting (n=4,900, 30.8%).

Table 1:Demographic characteristics & comorbidities.

Table 2:Migraine characteristics.

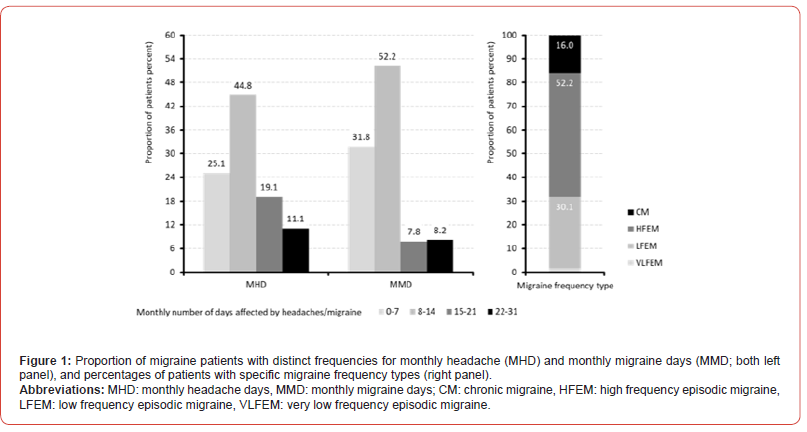

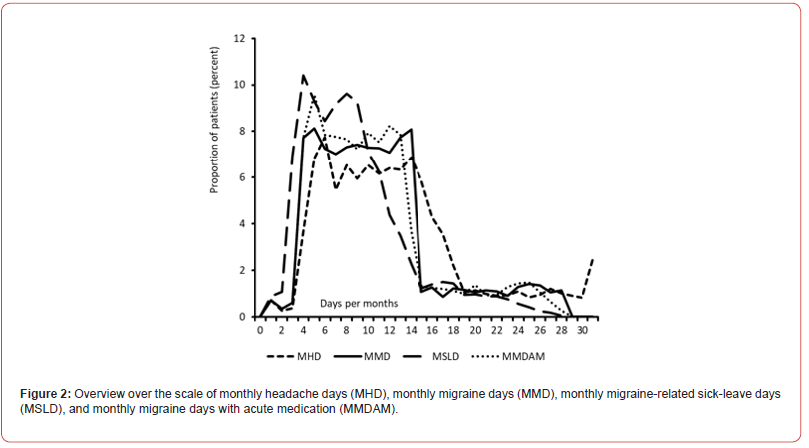

The average number of monthly headache days reported to the GPeR was 12.5±6.7 (median 11, range 1-31) days and the number of monthly migraine days was 10.9±5.8 (median 10, range 1-28; percentage with more than MMD per month was 90.6%; see table 2). The average number of monthly days with acute medication was 10.4±5.5 (median 10, range 1-28) days. Based on the monthly headache/ migraine days, 16.0% of migraine patients were diagnosed with chronic migraine and 84.0% with episodic migraine - either with high (52.2%), low (30.1%) or very low attack frequency (1.7%; Figure 1). On average, the frequency of monthly migraine-related sick leave days (MSLD) was 8.8±4.9 (median 8, range 1-28). 53.8% of all patients reported MSLDs of more than 7 days (n=8,563), only 2.0% (n=312) reported a maximum of two MSLDs per month; figure 2). At the time of documentation, roughly one third of patients reported some kind of dynamics within their migraine experience characterized either by an increase of attack frequency (25.1%), increase in pain intensity (30.9%), changing migraine character (12.7%), or an overall increasing impact on their everyday life (46.0%).

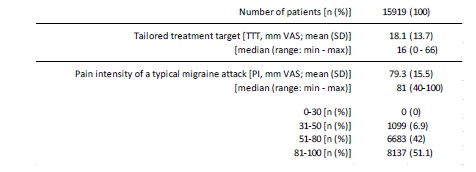

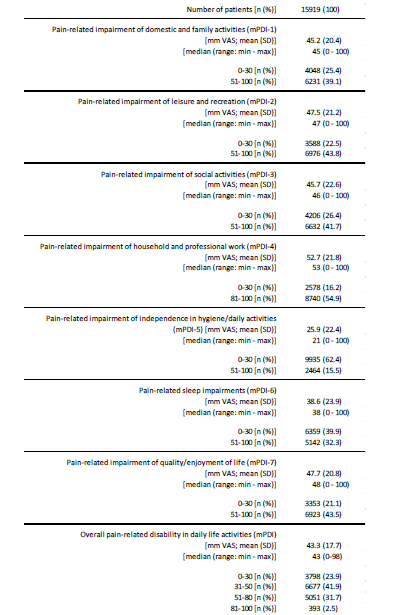

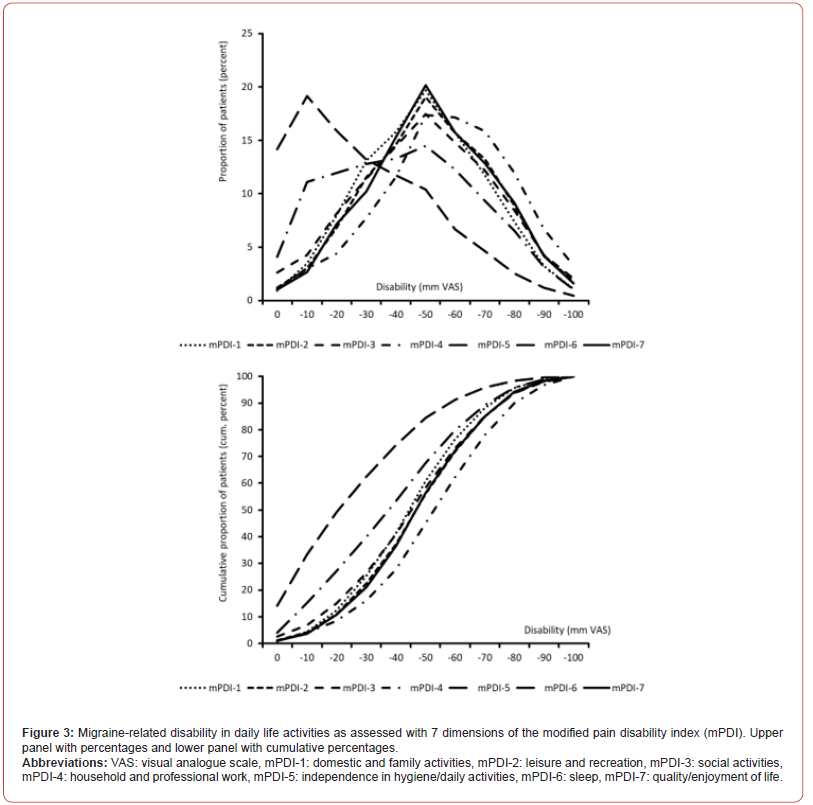

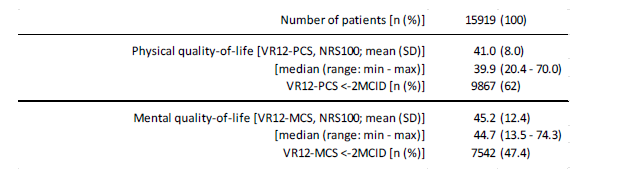

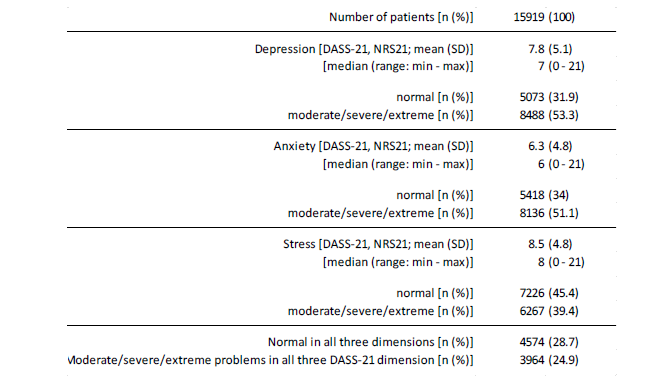

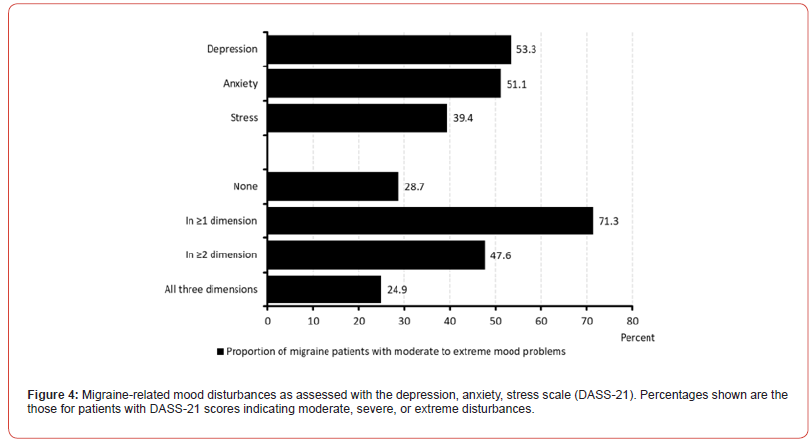

Patients described the pain intensity of their typical migraine attacks on average with 79.3±15.5 (median 81, range 40-100) mm VAS (Table 3) and the extent of migraine-related impairments in daily life (as assessed with the modified pain disability index) with 43.3±17.7 (median 43, range 0-98) mm VAS (Table 4). The physical quality of life was reported by the evaluated patients with reference to the physical component scale of the VR12 (PCS) with a mean of 41.0±8.0 (median 39.9, range 20.4-70.0). 62.0% of all patients (n=9,867) reported remarkably low VR12-PCS scores that were more than two standard deviations below the normal range (Table 5). With reference to the mental component scale of the VR12 (MCS), patients reported an average mental quality of life of 45.2±12.4 (median 44.7, range 13.5-74.3). 47.4% of all patients (n=7,542) reported conspicuously low VR12-MCS scores more than two standard deviations below the normal range. With reference to the German version of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scale (DASS- 21), the patients documented a mean level of depression of 7.6±5.1 (median 7, range 0-21), an average anxiety level of 6.3±4.8 (median 6, range 0-21), and a stress level of 8.5±4.8 (median 8, range 0- 21; see Figure 4 and Table 6). Almost three out of ten patients (26.9%) had at least severe depression scores, almost four out of ten patients (37.5%) showed at least severe anxiety disorders, and 21.3% showed at least severe stress values. All in all, every fourth patient (24.9%) showed at least moderate impairment in all three dimensions of the DASS-21, and seven out of ten patients (71.3%) showed corresponding abnormalities in at least one of the three dimensions assessed with the DASS-21.

Table 3:Migraine attack pain intensity characteristics.

Table 4:Migraine-related disabilities in daily life activities – part 1 (mPDI).

Table 5:Physical and mental quality-of-life (VR12-PCS/MCS).

Table 6:Mood disturbances (DASS-21).

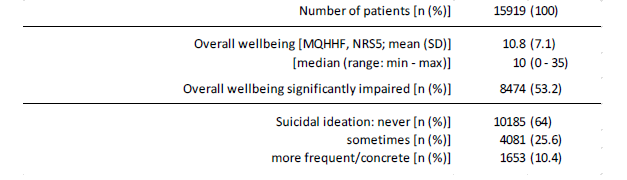

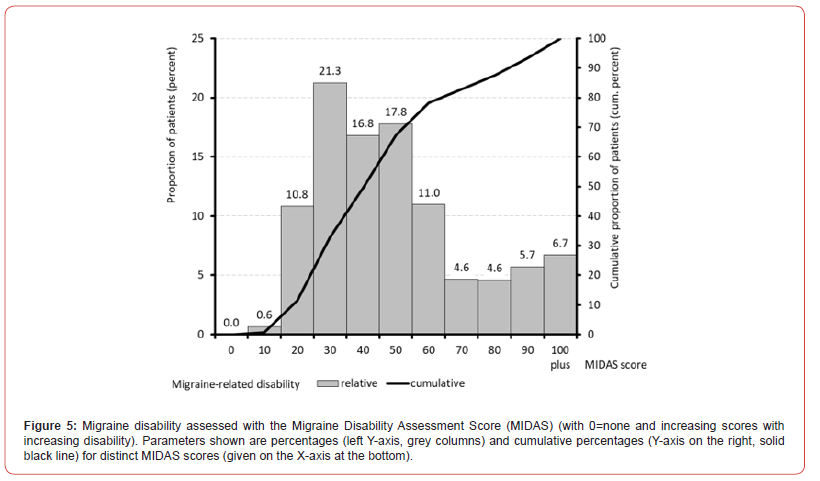

More than half of the migraine patients (53.2%) documented a noticeable reduction in their general well-being as a result of their migraine disease, and a quarter (25.5%) even reported severe restrictions in this regard (Table 7). More than every third patient (36.0%, n=5,734) stated that he “sometimes” had suicidal thoughts, 10.4% even “more frequently” or “specifically”. The extent of functional impairment due to their migraine headaches in the three months preceding the time of initial documentation in the German Pain e-Registry was documented by the migraine patients in this analysis as 45.5±24.1 on average (median 42, range 3-117). More than half of the patients (n=8,030, 50.4%) documented MIDAS scores of 50 and higher, one in five (21.7%, n=3,453) scores of 70 and higher (see figure 5). Based on the categorization instructions of the MIDAS questionnaire, only 0.4% of all patients (n=58) had “no or only slight” impairment. A further 49 patients (0.3%) had a “slight” impairment and 1,706 (10.7%) had a “moderate” impairment.

Table 7:Overall wellbeing (MQHHF) and suicidal ideation.

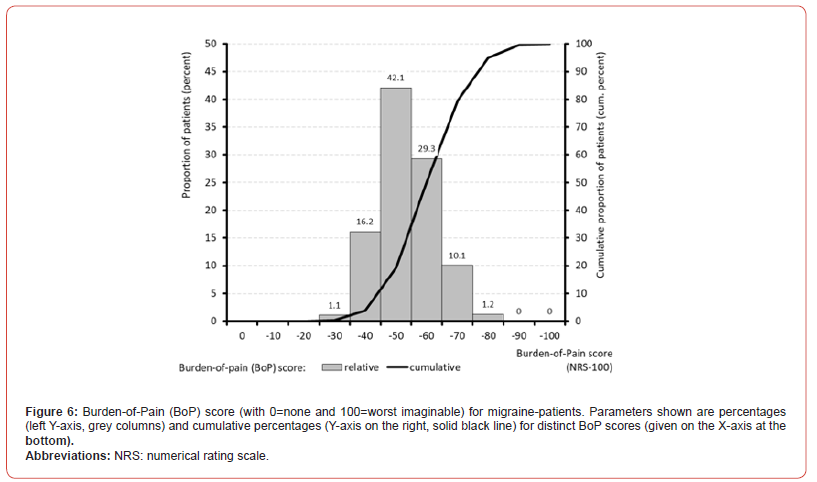

At 88.6% (n=14,106), almost nine out of ten patients documented at least a “severe” impairment, and over half of all patients (50.5%, n=8,038) even a “very severe” impairment. When asked about the seasonal dependence of their migraine, 37.5% (n=5,963) noted a maximum in winter. Analysis of the temporal kinetics of pain intensity with regard to time of day and day of the week revealed a focus on the night and morning as well as Saturday, Tuesday, and Sunday. With reference to the standardized scaled values for a) pain intensity, b) modified Pain Disability Index (mPDI), c) habitual well-being (MFHW), d) Quality-of-Life Impairment by Pain Inventory (QLIP), e) physical and f) mental quality of life (VR12- PCS/MCS), g) depression (DASS-D), h) anxiety (DASS-A), i) stress (DASS-S) and j) suicidality, a Burden of Migraine (BoM) index was calculated with a possible range of values for the pain-related burden of those affected between 0 (no burden) and 100 (maximum possible burden; see figure 6). With reference to this value, an average BoM index of 48.5±9.0 (median 48.0, range 23.6-79.9) was calculated for the patients in this evaluation. At 40.6% (n=6,465), four out of ten patients had a BoM index value of 50 or more as further evidence of severe migraine-related impairments in everyday life.

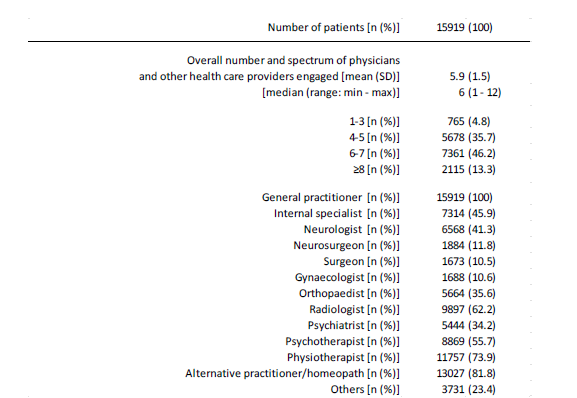

Engaged Physicians and Other Healthcare Providers

With regard to the question about the physicians and other practitioners previously consulted, the migraine patients evaluated stated a total of 93,435 contacts, which were distributed among various specialist groups according to the overview in table 8. Among the most frequently consulted physicians, general practitioners came first with 100%, followed by radiologists (65.2%), internists (with 45.9%) and neurologists (with 41.3%). With regard to non-medical therapists, the most frequent contacts were with physiotherapists (73.9%) and psychotherapists (55.7%). Alternatives to conventional medical approaches - e.g. by visiting homeopaths or alternative practitioners - were reported by 81.8%.

Treatment characteristics

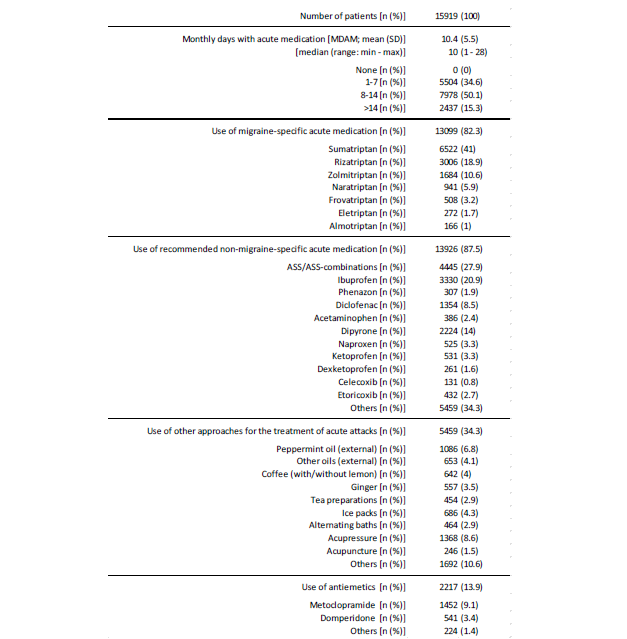

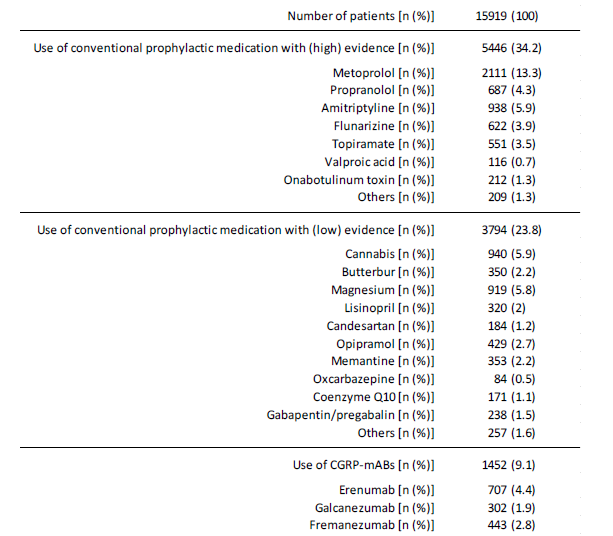

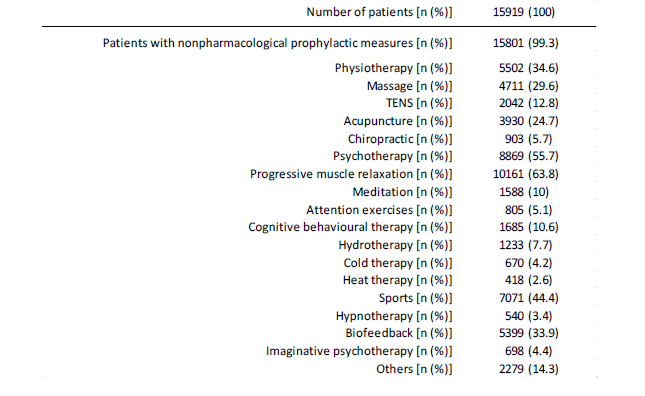

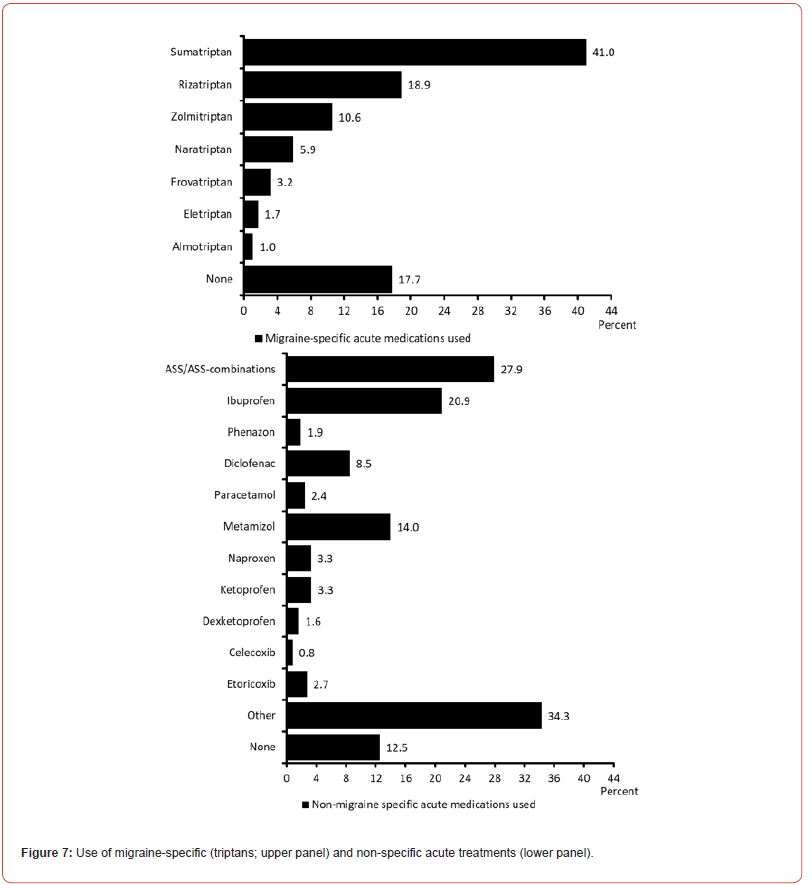

As part of their documentation through the GPeR, 82.3% of patients reported the use of a specific migraine medication in the form of a triptan – most frequently sumatriptan (41,0%), rizatriptan (18.9%) or zolmitriptan (10.6%) – for the treatment of their acute attacks (Figure 7 and Table 9). In addition, 87.5% of patients reported using additional guideline-recommended non-specific medications for the control of their acute migraine attacks (preferably from the group of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, 69.2%) and 34.3% also documented the use of non-specific, non-guideline- recommended therapies. Although the vast majority of patients (n=14,761, 92.7%), documented at least one gastrointestinal symptom as part of their migraine attacks, only 13.9% of all patients stated that these symptoms were specifically treated by the use of an antiemetic. Only 34.2% of patients reported using a drug prophylaxis with one of the guideline-recommended agents with high evidence - mostly ß blockers (17.7%), 23.8% documented the use of drugs with low/no evidence for their migraine prophylaxis – mostly cannabinoids (5.9%) and magnesium (5.8%), and only 9.1% the use of one of the newer monoclonal CGRP antibodies (Table 10). Non-drug prophylactic approaches were used by 99.3% of all patients – most prevalently progressive muscle relaxation techniques (in 63.8%), psychotherapy (in 55.7%), and aerobic sports/exercise (in 44.4%) (Table 11).

Table 8:Engaged physicians and other healthcare providers.

Table 9:Acute treatment characteristics.

Table 10:Pharmacological prophylactic treatment characteristics.

Table 11:Nonpharmacological prophylactic treatment characteristics.

Discussion

The study presented here examined demographic, therapeutic and bio-psycho-social aspects of migraine patients who sought help from a pain medicine center to alleviate their symptoms between 2015 and mid-2022 and provided detailed information on their clinical picture using the standardized documentation tools of the German Pain e-Registry. For the mentioned time interval, more 15,919 patients with migraine were identified who reported on their migraine and treatment characteristics. The presented results of the cross-sectional data analysis of this GPeR-data provides interesting insights into the real-world experience of migraine patients as well as their routine treatment patterns and their biopsychosocial burden within the German health care system. Although migraine as a primary headache disorder per definition clearly belongs to the field of neurology, only 41.4% of the migraine patients evaluated in this analysis reported that they had been treated by a neurologist or had at least consulted a neurologist about their headaches. Primary care providers in the truest sense of the word are the general practitioners in this group, who - at least according to the available data - consult other specialist groups depending on the case. Interestingly radiologists and internal specialists were significantly more frequent consulted than neurologists, what provides interesting insights into the objectives of the various consultations, which are obviously primarily aimed at ruling out secondary causes of headache and not primarily therapeutic approaches.

Also of interest are the documented pharmacological and non-pharmacological approaches for acute treatment, but especially for the preventive treatment of recurrent migraine attacks. While 82.3% of patients reported experience with the use of migraine- specific triptan therapies for acute treatment, only 34.2% of those affected stated that they had received preventive pharmacotherapy with a guideline-recommended prophylactic agent (with a high level of evidence) - even though nine out of ten patients in this study (90.6%) fulfilled the requirements described for the use of such therapies. Just under a quarter of patients reported the use of “alternative” prophylactic therapies with low/no evidence and as many as 9.1% documented the use of causally effective monoclonal antibodies against CGRP. If all the areas of prophylaxis mentioned are summarized, the number of patients “treated” prophylactically in accordance with the guidelines was 6,410, corresponding to around 44.4% of those patients for whom such an approach is appropriate and recommended. In contrast to the inadequate design of pharmacological options for the prevention of recurrent migraine attacks, the use or application of non-pharmacological alternatives was remarkable. Almost all patients (99.3%) stated that they used at least one non-pharmacological preventive measure, most frequently progressive muscle relaxation (63.8%), psychotherapy (55.7%) and aerobic exercise (44.4%).

The extent of migraine-related psychosocial stress was pronounced in the patient group we evaluated. Due to the frequency and intensity of the migraine attacks experienced, around a quarter of the patients had severe to very severe impairments in their participation in everyday life, regardless of the various areas of migraine-related impairment evaluated. In the MIDAS, 88.6% of patients documented scores above 20 as an indicator of “severe” impairment and 50.5% scores above 40 as a sign of “very severe” impairment. These impairments resulted not only in a relevant reduction in physical (in 62.0%) and mental quality of life (in 47.4%), but above all in critical mood and affect disorders, which resulted in relevant depressive moods in 53.3% of patients, anxiety disorders in 51, 1%, and significant stress levels in 39.4% - which, in the context of the complex biopsychological interactions in migraine genesis, must not only be regarded as significant co-morbidities in the sense of migraine-related secondary diseases, but also as disease- promoting trigger factors.

The fact that the general well-being of those affected is impaired in this context and that, at 53.2%, more than half of the patients in this study documented significant impairment of their overall well-being is therefore only partially surprising. The same applies to the extraordinarily high rate of study patients (25.6% and 10.4% respectively) who, when using the standardized documentation tools of the GPeR, stated that they at least occasionally or more frequently/concretely considered taking their own lives. This data from the GPeR impressively underpins the analyses of the Global Burden of Disease Study, which identified migraine as the second most important disease worldwide in terms of significant impairment of everyday life in its analysis of data from 2019 [23]. In their entirety, the data presented by us - the largest cross-sectional analysis of routine data from everyday care in Germany to date - provide a differentiated picture of the biopsychosocial stress and treatment characteristics of migraine patients who seek help in a specialized pain medicine facility to alleviate their symptoms. The information shown on practitioners and forms of treatment implemented to date must be an incentive to optimize preventive therapy measures in particular in order to alleviate the pronounced psychosocial stress caused by the high number of recurrent pain attacks and to enable those affected - despite their illness - to participate well in the activities of everyday private, social, and professional life without impairment.

Strength and Limitations

An important strength of the German Pain e-Registry is its focus on patient-reported data, while at the same time the entries are validated by experienced pain specialists. Another strength is the dual aim of generating data for research, but also supporting patients and physicians in their documentation and assessment of pain in everyday practice, and the possibility of sharing all information, which increases patient engagement. It should be noted that registry data can never be representative of the prevalence of the disorder in the general population. This is because, firstly, people with headaches who do not consult a physician who is part of the GPeR-network are not included. Secondly, the German Pain e-Registry focuses on centers with a special interest in pain, which keeps the data quality high, but results in a significant selection bias towards more severely affected patients. This problem is challenging, as it are mainly physicians with a special interest in pain who are willing to participate in such a registry. On the other hand, registry data are always observational. The resulting risks of bias include the lack of random assignment to therapies and the possible influence of treatment success on patients’ willingness to participate. What’s more, the obvious disadvantage of the fundamental lack of a control approach - especially for day-to-day practice - conceals the great advantage of low-threshold use. In this way, doctors and patients can document and evaluate what best meets their individual needs and requirements, and do not have to worry about externally defined framework conditions. This is a major advantage in improving individual patient care. Usage of the German Pain e-Registry is free of charge for both physicians as well as patients irrespective of their specialty or insurance status and the implementation of the underlying online system in daily practice routine is easy and its use is extremely timesaving for patients as well as practitioners and assistants thanks to the integrated evaluation routines and support services.

Conclusions

Migraine is a highly disabling, costly, under-diagnosed and under- treated headache disorder. It is the second highest burden of disease worldwide, and our cross-sectional analysis of routine data from daily practice confirmed this in Germany. Despite this, public and political awareness of migraine lags behind that of many other conditions (which have a lower prevalence and burden of disease). Patient-reported information - collected and assessed using standardized and highly validated approaches such as the online structures and applications of the German Pain e-Registry - are important tools used to measure burden and success of patient management approaches and should be implemented as mandatory tools when physicians care for patients with migraine.

Author Contributions

MAU was primarily responsible for the study concept and the biometrical analyses performed, and he also guarantees for the validity of the data as well as the integrity of the results. MAU also drafted the initial version of this manuscript and prepared all necessary tables and figures. All co-authors have made a substantial contribution to the work reported, be it conception, design, conduct, data interpretation, or all of these; have been involved in drafting, revising, or critically reviewing the article; have given final approval for the version to be published; have agreed on the journal to which the article will be submitted; and agreed to accept responsibility for all aspects of this work.

Funding

This research as well as the manuscript preparation were funded by an unrestricted scientific grant of the German Pain Association.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Data Availability

Due to restrictions of the EU data protection guideline and the standard operating procedures of the German Pain e-Registry the original datasets generated and analyzed for the current study are not available for external research.

References

- Lipton RB, Bigal ME, Diamond M, Freitag F, Reed ML, et al. (2007) Migraine prevalence, disease burden, and the need for preventive therapy. Neurology 68 (5): 343-349.

- GBD 2019 Diseases and Injuries Collaborators (2020) Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 396(10258): 1204–1222.

- Steiner TJ, Stovner LJ, Jensen R, Uluduz D, Katsarava Z (2020) Lifting the burden: the global campaign against H. Migraine remains second among the world’s causes of disability, and first among young women: findings from GBD2019. J Headache Pain 21(1): 137.

- Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS) (2018) The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd ed. Cephalalgia 38: 1-211.

- Lipton RB, Silberstein SD (2015) Episodic and chronic migraine headache: breaking down barriers to optimal treatment and prevention. Headache 55 (Suppl 2): 103-122.

- Merikangas KR (2013) Contributions of epidemiology to our understanding of migraine. Headache 53: 230-246.

- Radtke A, Neuhauser H (2009) Prevalence and burden of headache and migraine in Germany. Headache 49(1): 79-89.

- Woldeamanuel YW, Cowan RP (2017) Migraine affects 1 in 10 people worldwide featuring recent rise: a systematic review and meta-analysis of community based studies involving 6 million participants. J Neurol Sci 372: 307-315.

- Kröner Herwig B, Heinrich M, Morris L (2007) Headache in German children and adolescents: a population-based epidemiological study. Cephalalgia 27(6): 519-527.

- Yoon MS, Katsarava Z, Obermann M, Fritsche G, Oezyurt M, et al. (2012) Prevalence of primary headaches in Germany: results of the German Headache Consortium Study. J Headache Pain 13(3): 215-223.

- Rasmussen BK (2001) Epidemiology of headache. Cephalalgia 21(7): 774-777.

- Terwindt GM, Ferrari MD, Tijhuis M, Groenen MA, Picavet HSJ, et al. (2000) The impact of migraine on quality of life in the general population - the GEM study. Neurology 55(5): 624-629.

- Steiner TJ, Stovner LJ, Katsarava Z, Lainez JM, Lampl C, et al. (2014) The impact of headache in Europe: principal results of the Eurolight project. J Headache Pain 15(1): 31.

- Diener HC, Solbach K, Holle D, Gaul C (2015) Integrated care for chronic migraine patients: epidemiology, burden, diagnosis and treatment options. Clin Med (Lond) 15: 344-350.

- Shimizu T, Sakai F, Miyake H, Sone T, Sato M, et al. (2021) Disability, quality of life, productivity impairment and employer costs of migraine in the workplace. J Headache Pain 22(1): 29.

- German Pain Association. Manual for the German Pain Questionnaire (in German). The National Association of Statutory Health Insurance Physicians and the regional Associations of Statutory Health Insurance Physicians. Agreement on quality assurance measures according to 135 Para. 2 SGB V for pain therapy care of patients with chronic pain (German: Vereinbarung von Qualitätssicherungsmaßnahmen nach § 135 Abs. 2 SGB V zur schmerztherapeutischen Versorgung chronisch schmerzkranker Patienten).

- Von Korff M, Ormel J, Keefe FJ, Dworkin SF (1992) Grading the severity of chronic pain. Pain 50(2): 133-149.

- Tait RC, Chibnall JT, Krause S (1990) The Pain Disability Index: psychometric properties. Pain 40(2): 171-182.

- Kazis LE, Miller DR, Skinner KM Lee A, Ren XS, Clark JA, et al. (2004) Patient-reported measures of health: the Veterans health study. J Ambul Care Manage 27(1): 70-83.

- Hüppe M, Schneider K, Casser HR, Knille A, Kohlmann T, et al. (2022) Characteristic values and test statistical goodness of the Veterans RAND 12-Item Health Survey (VR-12) in patients with chronic pain : an evaluation based on the KEDOQ pain dataset. Schmerz 36(2): 109-120.

- Lovibond SH, Lovibond PF (1996) Manual for the depression anxiety stress scales. Psychology Foundation of Australia, Sydney.

- Nilges P, Essau C (2015) Depression, anxiety and stress scales: DASS–A screening procedure not only for pain patients. Schmerz Berl Ger 29(6): 649-657.

- Stewart WF, Lipton RB, Whyte J, Dowson A, Kolodner K, et al. (1999) An international study to assess reliability of the Migraine Disability Assessment (MIDAS) score. Neurology 53(5): 988-994.

- Steiner TJ, Stovner LJ, Jensen R, Uluduz D, Katsarava Z on behalf of Lifting the burden: the Global Campaign Against Headache (2020) Migraine remains second among the world’s causes of disability, and first among young women: findings from GBD2019. J Headache Pain 21(1): 137.

-

Michael A. Überall*, Heinrich Binsfeld, Dorothea Fago, Thorsten Lücke, Silvia Maurer, Norbert Schürmann and Johannes Horlemann. Demographics, Treatment Characteristics, and Bio-Psycho-Social Burden of Patients with Migraine Seeking Help from Pain Specialists in Germany-Results of a Cross-Sectional Analysis of Depersonalized Data Provided by the German Pain E-Registry. Arch Neurol & Neurosci. 17(1): 2024. ANN.MS.ID.000901.

-

Headache; Migraine; Bio-psycho-social burden; Quality-of-life; Depression; Anxiety; Stress; German pain e-registry

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.