Perspective Paper

Perspective Paper

Athletic Presentations of Functional Neurologic Disorders: Neurons That Error Together, Terror Together

Mike Studer, PT, DPT, MHS, NCS, CEEAA, CWT, CSST, CSRP, CBFP, FAPTA

Touro University, Henderson, NV, University of Nevada Las Vegas, Las Vegas, NV

Mike Studer, PT, DPT, MHS, NCS, CEEAA, CWT, CSST, CSRP, CBFP, FAPTA, Touro University, Henderson, NV, University of Nevada Las Vegas, Las Vegas, NV.

Received Date:December 02, 2025; Published Date:December 12, 2025

In his 1949 book, “The Organization of Behavior”, Donald Hebb coined the now famous phrase, “neurons that fire together, wire together” [1]. As our understanding of Functional Neurologic Disorders (FNDs) has evolved, we have come to understand the similarities between the phenotypes of FNDs in athletics (FND-As) commonly known by terms such as the Yips, Twisties, Flikkikammo, Motare and the very changes described in Hebb’s Theory. Advances in pain neuroscience, coupled with an improved understanding of FNDs brings us to an elevated time in the recognition and rehabilitation of FND-As. In this article, we will define the phenotypes of athletic presentations of FND-As and most importantly guide readers in an evidence-based and applications-filled manner that will include a framework for personalized clinical decision making.

Keywords: Functional neurologic disorders; pain; yips; twisties; flow; error; motor learning; neuroplasticity; nociplasticity

Introduction

Functional Neurologic Disorders in Athletes (FND-As) are both common to see, yet “between the lines”/on the field and in the locker rooms, are considered taboo to discuss. In this article, the author will bring the various subtypes of FND-As to light, comparing and contrasting the presentations. Additionally, readers can expect to see where the evidence of Functional Movement Disorders (FMD) applies to the athletic phenotypes, and what is left both uncovered by evidence and distinct from FMDs. Most importantly, the author will present the following subtopics as outlined in an effort to both unveil the discussion across all sports and elevate care, beginning with a recognition of the syndrome and the acceptance of conversations about it:

a) Differentiating and defining: FND, FMD and FND-A.

b) A distinction or continuum: FND-As, Dystonia and “choking under pressure”.

c) A Common Basis: Attentional Focus on Error Signals and Erroneous Body Parts in Functional Disorders and Pain.

d) The phenotypes of FND-A.

e) Proposed underlying neurophysiologies, endophenotypes, and predisposing factors.

f) A framework for rehabilitation: Personalized clinical decision making.

Differentiating and Defining: FND, FMD and FND-A

Functional Movement Disorders (FMD) are a subset of Functional Neurologic Disorders (FND) in which the person experiences involuntary movement of the body that most typically includes tremor, choreiform movement yet could also include profound weakness or a sudden give-way tendency. FMDs may include hand, head or body movements that persist through a person’s resting and active life. FMDs are often distinguished and ruled-in by two forms of variability - by environmental context and movement direction, entrainment, distraction and suggestion. While we will elaborate on these considerations, they are both detailed elsewhere and are not the intent of this article [2,3]. Similarly, FND-A will share context-specific and movement direction inconsistencies, distraction and suggestion. These similarities are not surprising, as practitioners should consider FND-A as a subset of FMD.

Aybek and Perez submitted the following definition of FND in their 2022 article, “...FND is a multi-network disorder involving abnormalities within and across brain circuits implicated in sense of agency, emotion/threat processing, attention, homeostatic balance, interoception, multimodal integration, and cognitive/motor control, among other functions.” [2].

This definition represents the experiences of FND (the larger umbrella), FMDs, and FND-As. There are notable differences between FMDs and FND-A in the experience, phenotype, contextual presentations and management. Some of these similarities and differences between common presentations of FMD and FND-A can be summarized as:

a) Most individuals with FND-A only experience their movement disorder within the context of their sport.

b) Persons with an FMD often experience their movement disorder across the entirety of their daily function. In contrast, for athletes with FND-A, their everyday movements are largely spared. Interestingly and most typically very similar movements outside of their sport are often spared. This will be an important point that can be leveraged in recovery, detailed later in this paper.

c) Persons with an FMD can be and are often burdened at rest and in motion.

d) Persons with an FMD are often burdened with their movement disorder across functional activities. FMDs are often less context- specific.

e) Some persons with FND-A are able to exhibit normal motor control outside of the context of competition. They may not experience a movement disorder in practice. Furthermore, expanding from point #1 above, they may be able to conduct the very same (triggering) action outside of their sport symptom free. Meaning, for any given movement (throw, dive, flip) an identical movement outside of this context are often normal.

f) The movement scale in FND-A is often a factor, with smaller “easy” movements more often afflicted. Examples include the shortest of throws, a short put “a gimmie”, “simply” releasing the arrow. This is not the case with most FMDs.

Aoyama and colleagues (2021) noted through a multiple comparison test that the frequency of throwing errors was significantly higher in short-distance throwing (same for putting) [4].

A Distinction or Continuum: FND-As, Dystonia and “Choking Under Pressure”

Healthcare, athletic training, coaching, and sports journalism have had a very uncomfortable relationship with describing and witnessing athletes that are struggling to perform at the level that they have previously demonstrated. When a person’s performance suffers under particularly important conditions (post season, rookie season, or a significant statistical milestone ahead), this is often excused-away as “choking under pressure”. However, these same observers referenced above (healthcare practitioners through journalists) may have a much more difficult time rationalizing performance that continues to be sub-par or particularly erroneous in regular-season or non-pressurized situations. When baseball players hit a ball squarely, but right at someone in the field - the hitless streak continues, yet this again is not representative of a Functional Neurologic Disorder in Athletes (FND-A). Athletes that experience a prolonged period of substandard performance that is described as “slump”, a “funk”, “hitting a rough patch”, or a “cold streak”. Although these periods of substandard performance that include cold streaks in hitting and shooting a basketball or having difficulty sticking a landing may not be in competition or in a playoff situation - athletes are still experiencing pressure to perform. Errors and cold streaks can be considered “part of the game”, the “law of averages” or in some situations as will be described below, “a regression to the mean”. These experiences are not representative of an FND-A as the movement is not aberrant and these athletes may just as quickly find resurgent performance and experience a period of flow. In many sports this is considered, “snapping out of it”, to use the most common phrase. To reiterate, movements in these athletes may not look aberrant. They may be just missing a put, a dive, a throw, a landing, a location, or seem to be experiencing a streak of bad luck.

When athletes experience an FND-A, they may be moving in a manner that is observably changed in activities that were once highly automatized. They may suddenly, “shank” a very short putt, missing wildly by angle or force. They may shoot an air ball more regularly. These athletes may be “unable to find” a backflip. In the throwing sports, an athlete might “spike” a ball unintentionally into the ground, or loft the ball over a teammate’s head, often when there is plenty of time and often during a very routine throw of 45 to 90 feet or less. The most common throwing yips in baseball are in fact the shortest - second base to first, pitcher to first, and catcher to pitcher. Similarly, athletes experiencing an FND-A might stop or “freeze” before releasing an arrow, engaging in a routine backflip, making a dismount from the parallel bars, diving board, or in the middle of a floor routine. For decades, these errors have been categorized as a sign of mental weakness, when in fact the athletes may be spending “too much” mental energy (attention) and are all-too aware of the problem, consequences, and ramifications.

Many authors have effectively differentiated a disorder that is functional in nature from an error that can be attributed to, “choking under pressure”. Recalling from point 5 above, that the easy movements are most commonly afflicted, we will now add the point that more experienced athletes (and musicians) are more likely to be impacted [5,6]. The brain circuits may not be weak, but rather, are just speaking the wrong language. Perhaps the “wrong circuits” are being used as a function of an individual trying too hard to either avoid an error or trying so hard to succeed that alternate brain circuitries attempt to control previously automatic movements. I experienced the Yips as a freshman baseball player in high school. I found myself as the starting third baseman on the varsity team, in 1984. While this article is built on the evidence in FND-A and FNDs in general, this article is also informed and translated through clinical experiences of our patients, and personal experiences lived. I have been there.

While the knowledge in this space continues to evolve, the dichotomy or continuum here deserves a deeper treatment on the topic. There is an as yet blurred-line between dystonia, FND-A’s, FMDs and experiences that are described as, “choking under pressure”. Adler and colleagues (2003) note abnormal co-contraction in the wrist musculature in Yips-affected golfers, labelling this focal dystonia [7]. In a related article penned by many of the same authors, Smith and colleagues (2003) describe the Yips as a movement disorder that is on a continuum between “choking under pressure” and task-specific dystonia [8]. While these lines remain blurred to some extent, there is increasing clarity over the last 20+ years regarding the functional nature of these conditions, the limited responsiveness to local dystonia-specific interventions (Botox), the positive responsiveness to top-down interventions (to be detailed below). Speaking to the other end of this continuum (choking under pressure) there are seeming contradictions between choking under pressure and the occurrence in experienced athletes across (mostly) many of the most automatic and simple movements within the sport (releasing an arrow, a throw from second base, tennis toss, short putts, and a toss back to the pitcher between pitches. Acknowledged exceptions include complex whole-body movements in gymnastics and diving (backwards movements from heights), noting that the cortical smudge and error-related negativity can be a separate phenotype, leading to an excessive internal focus in a whole-body task that has no time or place for body-part and internal focus as detailed below.

A Common Basis: Attentional Focus on Error Signals and Erroneous Body Parts in Functional Disorders and Pain

A former Major League Baseball player who preferred to remain anonymous was interviewed for this article. This athlete’s capacity to throw was affected by the Yips reviewed this article, and offered insights into his experience, writing,

“I went from having so much feel for the baseball and my brain would see a throw and the ball would rocket to the target and my fingers and arm stroke would feel and have confidence in what they were doing….to….literally having everything about throwing be totally foreign to my brain, fingers, arm stroke and it was terrifying for about a year or two until I learned to accept that foreign feeling at which case it caused me anxiety and embarrassment but wasn’t terrifying or paralyzing anymore” [9].

Although incompletely understood, we have a growing body of literature in amputation, in focal hand dystonia, and pain neuroscience that can inform our hypotheses and developing understanding of FND-As. Across these conditions, yet not exclusive to them, we understand the concepts of cortical smudging as well as a combination of both increased attention to and increased cortical representation of a problematic or symptomatic body par Jayathilake and colleagues (2025) write about the nociplasticity of chronic pain, “Both nociceptive and neuropathic pain share common features of neural adaptation and plasticity that contribute to pain chronification…Central to this understanding is the concept of maladaptive neural plasticity: the nervous system’s ability to reorganize its structure, function and connections in response to persistent pain signals, often in ways that perpetuate rather than alleviate the pain state” [10].

As referenced above, many individuals with chronic pain and FNDs experience an enhanced error-related negativity. While this syndrome is most widely recognized in disordered mental health and is primarily cited in psychology and in the field of pain neuroscience. Clearly, athletes with FND-As at all competitive levels experience both external and internal sources of criticism - increasingly so at professional levels. If they are not reminding themselves of their errors - others are [11]. Hajcak and colleagues (2004) write regarding error-related negativity (ERN), “The ERN is a negative deflection in the event-related potential that peaks approximately 50 ms after the commission of an error. The ERN is thought to reflect early error-processing activity of the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC)” [11].

Related, the ACC has known responsibilities in attention regulation, error detection, and decision making - a triple play of sorts that can capture an error, increase attention and play a role in either compensation or avoidance. We see overlapping mechanisms (including the ACC) in persons with persistent pain [10]. Prolific researcher and author Debbie Crews (a contributing author in the Smith, 2003 and Adler, 2005 articles cited previously) speaks about her research on the Yips in golf and states, “We think it’s (the Yips are) about anxiety. The reality is, it’s not about anxiety…it simply exacerbates the condition…if we come in there with beta blockers and (interrupt the effects of the Yips), they don’t go away - the players just don’t feel the effects.” Crews continue on to explain that golfers continue to have the abnormal co-contractions as evidenced by the EMG readings, yet do not perceive that they are committing the errors [12].

As noted above (Smith, 2003, which includes Crews and colleagues) many have postulated the existence of a continuum, from dystonia to “choking under pressure”. Is it possible that anxiety is present in some of these athletes, or fear? Is there a role for a scale to measure and record fear in persons with an FND-A? Perhaps thiscould further develop the different subtypes and endophenotypes, the presence of kinesiophobia, or fear of errors, or not/none? The Tampa Scale of Kinesiophobia (TSK) was developed in 1991 by colleagues R. Miller, S. Kopri, and D. Todd. These authors were the same group that coined the term kinesiophobia just 3 years prior to this publication. Miller and colleagues wrote (about kinesiophobia) that is characterized by, “an excessive, irrational, and debilitating fear of physical movement and activity resulting from a feeling of vulnerability to painful injury or reinjury”. Again, relating pain to Functional disorders, what if we substituted the words “error or embarrassment” for “painful injury or reinjury”? Could a person be kinesiophobic when a movement has caused them shame, rather than pain? Indeed. While this scale is only validated (and worded to assess) persons that may have fear of a recurrent injury, or fear of pain - there may be promise to be found in developing something similar for persons with an FND-A [13,14].

There are increasing similarities discovered between many of the most persistent conditions - from pain to functional conditions, phobias and the like. For example, we see the commonality of cortical smudging in dystonia, Functional Movement Disorders (FMDs) and FND-As. The literal blurring of body parts evident through imaging in sensory homunculus as evidenced in focal dystonia and in persistent pain. To learn more about what is known regarding FND-specific changes in the brain, readers are directed to early works by Prabhakar and colleagues (2006); as well as recent developments by Moayedi et al, 2021; Doricchi et al., 2022; Walpola et al., 2025; and Weber et al., 2025 in FND regarding the Extrastriate Body Area (EBA) - one of many functional collections located at the right Temporo-Parietal Junction (R TPJ) [15-19]. Weber and colleagues, citing Edwards and colleagues (2011) [20] wrote, “the right temporoparietal junction (rTPJ) has been assumed to act as a key node in the comparator model, in which intention-based motor plans deriving from the supplementary motor area (SMA) and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) are compared to actual motor outcome forwarded from the sensory system” [19].

Both static imaging and dynamic analyses of brain activity/ connectivity are both advancing our understanding of the neural underpinnings of FNDs across all types. Whereas EEGs might have previously been our best source to rule-in Functional Seizures, with the conversation stopping there, we have advanced to include PET scans, fMRI and more. Most recently, Müller and colleagues (2025) demonstrated that an fMRI may provide insights for sense of agency (SoA) which will be explored more in the upcoming pages. It is timely and noteworthy that we remind ourselves of the words of the MLB player quoted above (a common description and one that resonates with many interviews as well as my own experiences), “I lost my body part”. These very words have been paraphrased by Simone Biles experiencing the Twisties, “I feel like I am lost in the air”; Ernie Els on putting, ““Snakes and stuff going up in your brain” and “a short” in my brain; retired pitcher Rick Ankiel describes, “... you throw one pitch and…my mind goes, ‘Oh, no. Here we go again. It’s almost like I cannot feel the ball. It’s like a mini-blackout.”. This loss of a body part or the whole body is a shared experience with the diffuse, dynamic and anomalous nature of symptoms as described by individuals with FMDs, pain, FNDs and FND-A’s as well as the increasingly- more-easily triggered nature of symptoms in persistent pain and Persistent Postural Perceptual Dizziness (PPPD). Readers are directed to the IASP definition of persistent pain and the Barany Society’s criteria for PPPD with notable commonalities of the aforementioned ease of triggering as well as the “wandering nature” of symptoms that are difficult to localize and are additionally variable in description, intensity and expanding-nature of triggers [21,22].

Continuing on with another quote from Weber (2025) - now on the topic of Sense of Agency (SoA) to complement this referenced excerpt from our baseball player, complemented by the IASP and Barany Society, we read, “The SoA has been postulated to be disrupted in FND patients as they experience their symptoms being produced involuntarily, even though the involvement of voluntary corticospinal pathways is existing, observable in clinical examinations disclosing entrainment or distractibility” [19]. Fiorio et al., 2022 explored personality, perception and neuroanatomy in their study using placebos and nocebos in both diagnosis (ruling-in) and treatment. The group stated, “Here, we propose that this relationship (placebos & nocebos in FND) might go beyond diagnosis and therapy. We develop a framework…(which) might offer guidance for clarification of the pathogenesis of FND and for the identification of potential biomarkers and therapeutic targets” [23].

Predictive coding could be faulty in persons with all types of FND, athletic, cognitive, seizure, movement (gait, tremor, weakness, paralysis) and sensory (persistent dizziness). In a very powerful excerpt from their 2024 article, Gonzalez-Herrero and colleagues suggest that, “…the brain uses internal generative models acquired through experience or mental simulation to continuously generate descending (top‐down) predictions of expected sensory data, which, to a variable extent, can modulate or gate incoming sensory information. These top‐down predictive signals from higher order brain structures continually update (learning) to minimize discrepancy with incoming ascending (bottom‐up) sensory signals to build a representation of the “world”. Sometimes, even without direct access to what is causing the registered sensory information, meaning is obtained from past events that seem similar to the current state of the body and environment, a process called causal inference. This ability to infer which hidden environmental structure may have generated observed sensory signals is essential to behaving adaptively…(interoception)” [24].

Attempting to repress, ignore, deny (sensory, cognitive, psychological, autonomic) or to regulate motor control over (movement, gait). Using an alternative neural network to control a previously established pathway (oversimplified). Mental health is nearly inextricable from discussions of functional neurologic disorders. It is clear from the literature that mental health conditions such as anxiety and obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) will increase the likelihood of experiencing an FND. Functional Neurologic Disorders in athletics are no exception. The literature of FND-As covers tendencies of perfectionism and as referenced previously response to errors. It does not appear to advance the discussions of FNDs to talk more about mental health conditions at this point, yet the consideration of endophenotypes may improve our ability to be presentation (and person) specific. Aoyama and colleagues discuss this in their previously referenced 2021 article, writing,

“The psychologically triggered yips group had significantly higher agreeableness scores compared with the non-yips group, whereas the non-psychologically triggered yips group had significantly higher neuroticism scores compared with the psychologically triggered yips group. In the non-psychologically triggered yips group, there was a significantly higher frequency of throwing errors than in the psychologically triggered yips group, with a tendency to develop yips symptoms gradually. The agreeableness score of the psychologically triggered yips group was significantly higher than that of the nonyips group, but not significantly different from that of the non-psychologically triggered yips group. Therefore, it is possible that the non-psychologically triggered yips group also included some players with high agreeableness scores. Since the reason for this cannot be mentioned from the results of this study, further investigation with a larger sample size will be necessary.”

Our understanding of agency, error related negativity (noted earlier), body schema and interoception continue to develop, yet is currently incomplete at best. As noted above, for persons with an amputation, individuals with a focal, those experiencing persistent pain and seemingly for Functional Movement Disorders, these capacities may be impaired in a related fashion. This may be referred to as cortical smudging, nociplasticity (term reserved for pain), or be represented by hypointensity in centers that are known to represent the body in relationship to our environment and other body parts. Perhaps a “4-A” model would be appropriate to ascribe, those being:

a) Attention (elevated toward an aberrant body part or movement).

b) Awareness (tying back to the error related negativity).

c) Activity (triggering movement).

d) Area (increasing representation in and smudging of motor and sensory homunculi).

The information that we have about this section on personality, neuroanatomy, dysfunctional neuroplasticity, neurodivergence, mental health, response to errors and perception can be summarized, yet not concluded. Much more research is being conducted and is still needed. From Clarke and colleagues’ article (2020), we read that personality has a high capacity to predict Yips and discriminate such from choking under pressure. The authors list, “fear of negative evaluation, individual differences, anxiety sensitivity, self-consciousness, perfectionistic self-presentation, and perfectionism” among these predictive variables [25]. Recalling Debbie Crews (referenced previously) clearly advocating that these errors are not about anxiety to Aoyama and colleagues4 noting personality differences (agreeableness) separating different presentations of persons with the Yips. The field is beginning to arrive toward a singular consensus of predictive factors and endophenotypes.

The Phenotypes of FND-A

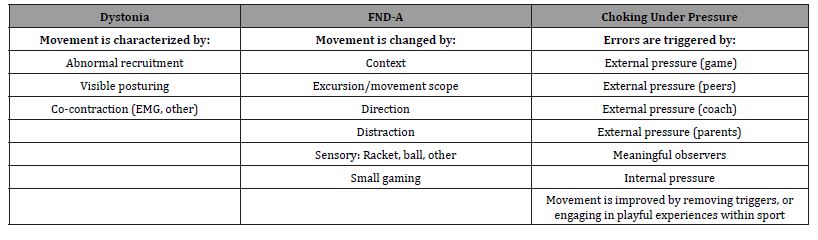

As noted above, Crews and colleagues refer to a continuum from dystonia to choking under pressure. Some refer to these as Type I and Type II Yips. Perhaps the Functional Movement Disorder “variety” of sport-related movement errors (FND-As) are not covered by either of these, and instead lies in the middle - not dystonia and not “choking”. Table 1 offers visual clarity on this third (middle) subtype, along with characteristic features that might represent and in some, improve each Table 1.

Table 1:The Continuum of Dystonia through FND-A and Choking.

The Phenotypes of the most common FND-As include [26-35]:

a) Yips: Baseball throwing or holding onto the bat, short putts in golf, second serve and service toss in tennis

b) Twisties: The inability to coordinate a previously well-known or established routine in gymnastics. Most often includes the uneven bars or flips in a floor routine.

c) Flikkikammo: The inability to produce a backward movement that has previously been well known or established. Most often includes a back handspring, backflip or back dive.

d) Motare: The inability to release an arrow (archery) when the target is in sight.

e) Hanare: Prematurely releasing an arrow (archery).

Historically, there have been many high-profile examples of the FND-As in sports. In baseball, some of the most notable include Pittsburgh Pirates pitcher, second basemen Chuck Knoblauch and Steve Sax, as well as other notable pitchers with difficulty finding the plate (Rick Ankiel) and finding first base (pickoffs or for a forceout at first) (Jon Lester). A most prolific example, if not singular, is Simone Biles in gymnastics. In tennis, the service toss with Karol Kucera and second serves (many), most notably Anna Kournikova. In golf, Bernhard Langer, Ernie Els and many others. Although there are fewer prolific examples, we see full-body and extremity-specific movement disorders in cheer, diving, American football (throwing and placekicking), as well as pickleball (serves). As discussed above, there may be some emerging commonalities leading to respective endophenotypes including response to error, sense of agency, tendencies toward perfectionism, and interoception. A commonality across the sports and individuals continues to be those with experience (not a novice) and in many of the most routine/overlearned movements.

A Framework for Rehabilitation: Distinguishing features of FMD from FND-A Management

Functional Neurologic Disorders in Athletics are a subtype of Functional Movement Disorders. The literature of Functional Movement Disorder rehabilitation is becoming extensive and does not need to be fully reiterated, yet could be summarized here to include [36-38]:

a) The importance of a multidisciplinary team.

b) Including the patient in the education and diagnosis of a functional disorder.

c) Exploration of sensory preferences (environmental contexts, sensory overloads, sensory engagements and sensory distractions (explored below). These can be stated or observed.

d) Leveraging distractions in diagnostics and to deepen treatment engagement.

e) Top-down strategies to mitigate the effects of triggers/triggering environments or tasks.

f) Bottom-up strategies to do the same, mitigate the expression of a movement disorder and effects of a potentially triggering context or task.

g) How would or could the management of a Functional Neurologic Disorder in Athletics be different? This is an arena that experiences a paucity of research, potentially due to the polarization of Type I (dystonia) and Type II (choking under pressure) without room for the proposed middle-ground that is experienced yet not researched of a third type, the FND-A, being more related to Functional Movement Disorders. A few common differences in sport, that do not necessarily separate every FND-A from a more common life and work-based presentation of an FMD could include:

a) Personality differences (opportunities) with competitive athletes: Affording gamification and (potentially) gameful loss aversion as motivators.

b) Multidisciplinary team could now include coaching staff.

c) Dynamics of a team supporting and counting on the athlete.

d) Prior exposure to pressure and relationship with pressure.

e) Compensatory opportunities: Change movement strategies, change position in sport.

f) Familiarity with other sports and success away from the triggering sport (as compared to persistent experience of an FMD).

A Framework for Return to Sport with a Functional Neurologic Disorder-Athletic

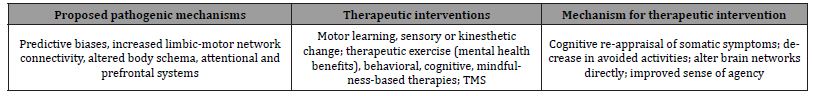

Table 2:Contemporary Models of FND with Associated Management.

A small change in the movement approach can temporarily “solve” (compensate for) the aberrant movement. In baseball, a common approach is to either loft the easy throw back, or change arm slot (angle). This can temporarily avoid the problem yet may leave the athlete with fewer options when demands for a timely (quick throw), higher velocity throw or the complexity of a throw is elevated (baserunner obstructing, unfamiliar angle). In many situations a sensory cue, a change in “approach” or routine, and even a movement compensation can draw both more intention and attention to the problem. As the aberrant movement was once automatized, procedural or “automatic”, using more cognitive and attentional resources to circumvent the problem may be an effective yet temporary work-around, until the speed of play or pressure of the situation makes a compensation either unavailable or ineffective. Even worse, a conscious control pattern, thinking about a second serve angle or cut, a throw, putt, backflip or tumble, can increase the previously-referenced network and nociplasticity-like dysfunction, dependent on attention, leaving the athlete farther from recovered and little more than temporarily compensated Table 2.

Many contemporary articles describe the neurophysiology, the connection gradients, predisposing factors, and the phenotypes of these invisible conditions. In this article, we have provided a novel contribution by curating evidence-on and describing the commonalities between these conditions of pain, dystonia, FNDs and FNDAs [39]. It is at this time that we create yet another novel separation from existing literature by suggesting a clinical pathway toward returning a person to optimized function in sport, overcoming an FND-A. As business and motivational-leader Jim Rohn says, “We must focus on solutions, not the problems”. Due to the heterogeneity of these presentations and even more importantly the individuality of people themselves, it may be better to think of the management of most any Functional Neurologic Disorder (athletics or otherwise) as a framework rather than truly a clinical pathway.

Specific to FND-As, based on literature, extensive professional and competitive athlete experience and personal experience in recovery, we offer the following framework noting that the management for persons with FMDs (listed above) is assumed:

a) Understand this athlete’s relationship with and preferences for errors (frequency, consequences), and gamification.

b) Provide the individual with experiences success in the body part, away from the athletic movement - even if this movement does not “look like”/represent the triggering sport motion.

c) Identify sensory additions and subtractions that benefit the athlete in the out-of-sport participation (weight vest, body part sleeve (compression), brace or splint, music).

d) Identify healthy (effective) distractions that feel playful, salient or challenge-point difficult for this person. Note: Athlete is involved in ascribing the dosage.

e) Provide the individual autonomy and agency in adjusting the tasks, error rate, gamification opportunities and steady progression back toward sport-specific experiences.

f) Resist the temptation to consistently praise this individual. Afford them an opportunity to rate themselves and provide their own feedback prior to therapist feedback.

g) Consider the “Unload-Load-Unload” approach out of sport and gradually in-sport contexts.

1. Participate in a challenging - not triggering - task in its basic form (unloaded).

2. Participate in the same task with an additional element (loaded).

3. Athlete is wearing/enduring: Weight vest, pressure-timed, ankle weights, heavier resistance, obstacle course or other.

4. Participate in the unloaded task again, affording the opportunity for a quick win.

h) Systematically remove sensory strengths (vision, stable surface or other).

i) Loading a sensory system (removing sensory strengths).

j) Gradually re-introduce the athlete back to the triggering sport using small games, playful opportunities that are not fully sport-like (court size, number of defenders, rules). Read more in the Constraints Led Approach.

A note on sensory cues and compensation from Rhodes & May (2021) may be valuable here. The authors offer the following description of applications that are bottom-up and top-down in their 2021 article leveraging applied imagery, “To refocus attention, athletes use pre-planned cues such as a deep breath out or a slow sip of water. The rationale behind cues, particularly the deep breath out, lies in their ability to shift the body from a sympathetic state (characterised by racing thoughts, and an elevated heart rate and cortisol levels) to a parasympathetic state, which mitigates anxiety. In addition, cues activate the next step - planning through the use of imagery” [40].

Rhodes & May (2021) continue, “In my work with Olympic athletes, we explore a variety of performance scenarios using multi-sensory imagery: the sounds of the crowd, the smell of the track, the movements as you compete, colours, sights, and the strategies for controlling emotions. This process develops familiarisation and evokes motivation”. The model concludes with a commitment behavioural cue, such as self-talk or a leg tap. For instance, during the Paris Olympics, you might have observed Biles mental model in action before the balance beam. She takes in a deep breath to refocus attention, plans by imagining her routine (we know this because her body is moving as she plays out what’s about to happen), and uses a commitment cue to affirm: ‘You got this!” [40].

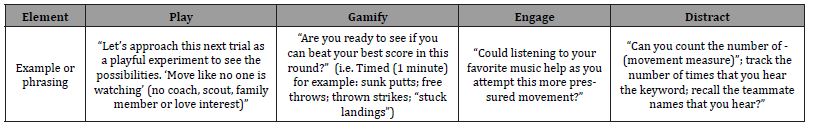

Table 3:The Distraction Model.

Finally, the reader is directed to Table 3 for an additional resource that may benefit their patient with FND-A. While distractions have long served as an element to differentiate or rule-in an FND and distractions can help some patients participate in a sport, Table 3 expands the discussion of distractions to serve as a rehabilitative tool (affording surprising success), a serviceable distraction to re-engage, as well as a “load” in the aforementioned “unload- load-unload” approach Table 3.

Clinicians would be well-advised to use these elements to diagnose, engage, distract toward external focus, be playful and afford a more person-specific dosage (intensity, error-frequency, duration). The field of research/body of knowledge on FND-As is not fully saturated and could benefit from improvements in recognition, acceptance, phenotyping, and screening tools. This article has attempted to merge the fields of sport science, sports psychology, movement disorders, neurology and rehabilitation to begin the necessary discussions around the clinical management/frameworks of rehabilitation and the aforementioned gaps in knowledge.

Acknowledgement

None.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest.

References

- Hebb DO (1949) The organization of behavior: A Neuropsychological theory.

- Perez DL, Aybek S, Popkirov S, Kozlowska K, Stephen CD, et al. (2021) On behalf of the American Neuropsychiatric Association Committee for Research. A Review and Expert Opinion on the Neuropsychiatric Assessment of Motor Functional Neurological Disorders. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 33(1): 14-26.

- Mavroudis I, Franekova K, Petridis F, Ciobica A, Papagiannopoulos S, et al. (2025) Positive Clinical Signs in Functional Neurological Disorders: A Narrative Review and Development of a Clinical Decision Tool. Brain Sci 15(9): 997.

- Toshiyuki Aoyama, Kazumichi Ae, Hiroto Souma, Kazuhiro Miyata, Kazuhiro Kajita, et al. (2021) Difference in Personality Traits and Symptom Intensity According to the Trigger-Based Classification of Throwing Yips in Baseball Players. Front Sports Act Living 3: 652792.

- Knox J, Shah K, McFarland MM, Casucci T, Jones KB (2025) Prevalence and proposed aetiologies of dystonias or yips in athletes playing overhand sports: a scoping review protocol. BMJ Open 15(2): e091016.

- Sadnicka A, Kassavetis P, Pareés I, Meppelink AM, Butler K, et al. (2016) Task-specific dystonia: pathophysiology and management. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 87(9): 968-974.

- Adler CH, Crews D, Hentz JG, Smith AM, Caviness JN (2005) Abnormal co-contraction in yips-affected but not unaffected golfers: evidence for focal dystonia. Neurology 64(10): 1813-1814.

- Smith AM, Adler CH, Crews D, Wharen RE, Laskowski ER, et al. (2003) The 'yips' in golf: a continuum between a focal dystonia and choking. Sports Med 33(1): 13-31.

- Woolf CJ, Salter MW (2000) Neuronal plasticity: increasing the gain in pain. Science 288(5472): 1765-1769.

- Nishani JJ, Tien Thuy Phan, Jeongsook Kim, Kyu Pil Lee, Joo Min Park (2025) Modulating neuroplasticity for chronic pain relief: noninvasive neuromodulation as a promising approach. Exp Mol Med 57(3): 501-514.

- Hajcak G, McDonald N, Simons RF (2004) Error-related psychophysiology and negative affect. Brain Cogn 56(2): 189-197.

- The Golf Improvement Podcast - Dr. Debbie Crews Interview - The Yips!. The Golf Improvement Podcast (2015).

- Miller R, Kori S, Todd D (1991) The Tampa Scale: a measure of kinesiophobia. Clin J Pain 7(1): 51-52.

- Hudes K (2011) The Tampa Scale of Kinesiophobia and neck pain, disability and range of motion: a narrative review of the literature. J Can Chiropr Assoc 55(3): 222-232.

- Prabhakar AT, Inturi S, Roy A, Kumar S, Margabandhu K, et al. (2024) Acute transitory head mislocalization - a novel syndrome of pathological embodiment in a patient with traumatic brain injury - a case study. Neurocase 30(2): 73-76.

- Moayedi M, Noroozbahari N, Hadjis G, Themelis K, Salomons TV, et al. (2021) The structural and functional connectivity neural underpinnings of body image. Hum Brain Mapp 42(11): 3608-3619.

- Doricchi F, Lasaponara S, Pazzaglia M, Silvetti M (2022) Left and right temporal-parietal junctions (TPJs) as "match/mismatch" hedonic machines: A unifying account of TPJ function. Phys Life Rev 42: 56-92.

- Walpola IC, Mohan A, Foster S, Kozlowska K (2025) Altered self-processing brain networks in paediatric functional neurological disorder. Neuroimage Clin 47: 103811.

- Weber S, Bühler J, Bolton TAW, Selma Aybek, et al. (2025) Altered brain network dynamics in motor functional neurological disorders: the role of the right temporo-parietal junction. Transl Psychiatry 15(1): 167.

- Edwards MJ, Moretto G, Schwingenschuh P, Katschnig P, Bhatia KP, et al. (2011) Abnormal sense of intention preceding voluntary movement in patients with psychogenic tremor. Neuropsychologia 49(9): 2791-2793.

- Treede RD, Rief W, Barke A, Aziz Q, Bennett MI, et al. (2019) Chronic pain as a symptom or a disease: the IASP Classification of Chronic Pain for the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11). Pain 160(1): 19-27.

- Staab JP, Eckhardt-Henn A, Horii A, Jacob R, Strupp M, et al. (2017) Diagnostic criteria for persistent postural-perceptual dizziness (PPPD): Consensus document of the committee for the Classification of Vestibular Disorders of the Bárány Society. J Vestib Res 27(4): 191-208.

- Fiorio M, Braga M, Marotta A, Villa-Sánchez B, Edwards MJ, et al. (2022) Functional neurological disorder and placebo and nocebo effects: shared mechanisms. Nat Rev Neurol 18(10): 624-635.

- Gonzalez-Herrero B, Happé F, Nicholson TR, Morgante F, Pagonabarraga J, et al. (2024) Functional Neurological Disorder and Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Complex and Potentially Significant Relationship. Brain Behav 14(12): e70168.

- Clarke P, Sheffield D, Akehurst S (2020) Personality Predictors of Yips and Choking Susceptibility. Front Psychol 10: 2784.

- Maaranen A, Van Raalte JL, Brewer B (2019) Mental blocks in artistic gymnastics and cheerleading: Longitudinal analysis of Flikikammo. Journal of Clinical Sport Psychology 14(3): 251-269.

- Maruo Y, Shimizu K, Miyamoto T (2025) Exploring Throwing Yips in Youth Baseball Players: Prevalence, Symptoms, Players' Psychological Characteristics, and Triggers. Percept Mot Skills 132(2): 353-373.

- Haber LA, Taylor EM (2024) The Procedural Yips. J Gen Intern Med 39(9):1764-1765.

- Ogiso T, Ono Y, Suzuki S, Shimohata T (2023) Clinical Neurology. Abnormal movements "Motare" in Kyudo have the characteristics of task-specific focal dystonia. Rinsho Shinkeigaku 63(8): 532-535.

- Lenka A, Jankovic J (2021) Sports-Related Dystonia. Tremor Other Hyperkinet Mov (N Y) 11: 54.

- Mesagno C, Beckmann J (2017) Choking under pressure: theoretical models and interventions. Curr Opin Psychol 16: 170-175.

- Harris DJ, Wilkinson S, Ellmers TJ (2023) From fear of falling to choking under pressure: A predictive processing perspective of disrupted motor control under anxiety. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 148: 105115.

- Maaranen A, Beachy EG, Van Raalte JL, Brewer BW, France TJ, et al. (2017) Flikikammo: When gymnasts lose previously automatic backward moving skills. Journal of Clinical Sport Psychology 11(3): 181-200.

- Giannì C, Pasqua G, Ferrazzano G, Tommasin S, De Bartolo MI, et al. (2022) Focal Dystonia: Functional Connectivity Changes in Cerebellar-Basal Ganglia-Cortical Circuit and Preserved Global Functional Architecture. Neurology 98 (14): e1499-e1509.

- Perruchoud D, Murray MM, Lefebvre J, Ionta S (2014) Focal dystonia and the Sensory-Motor Integrative Loop for Enacting (SMILE). Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 8: 458.

- Raynor G, Baslet G (2021) A historical review of functional neurological disorder and comparison to contemporary models. Epilepsy Behav Rep 16: 100489.

- Nicholson C, Edwards MJ, Carson AJ, Gardiner P, Golder D, et al. (2020) Occupational therapy consensus recommendations for functional neurological disorder. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 91(10): 1037-1045.

- Gilmour GS, Nielsen G, Teodoro T, Yogarajah M, Coebergh JA, et al. (2020) Management of functional neurological disorder. J Neurol 267(7): 2164-2172.

- Nielsen G, Lee TC, Marston L, Carson A, Edwards MJ, et al. (2025) Which factors predict outcome from specialist physiotherapy for functional motor disorder? Prognostic modelling of the Physio4FMD intervention. J Psychosom Res 190: 112056.

- Rhodes J, May J (2021) Applied imagery for motivation: A person-centred model. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology 20(6): 1556-1575.

-

Mike Studer*, PT, DPT, MHS, NCS, CEEAA, CWT, CSST, CSRP, CBFP, FAPTA*. Athletic Presentations of Functional Neurologic Disorders: Neurons That Error Together, Terror Together. Aca J Spo Sci & Med. 3(2): 2025. AJSSM.MS.ID.000557.

-

Functional neurologic disorders; pain; yips; twisties; flow; error; motor learning; neuroplasticity; nociplasticity; iris publishers; iris publisher’s group

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.