Review Article

Review Article

Swimming Safer: Three-Dimensional Drowning Prevention Level Test: Conceptual, Attitudinal and Procedural (CAP)

Marcelo Barros de Vasconcellos*

Specialist in Aquatic Activities, State University of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

PhD Marcelo Barros de Vasconcellos, Specialist in Aquatic Activities, State University of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

Received Date:July 17, 2025; Published Date:July 24, 2025

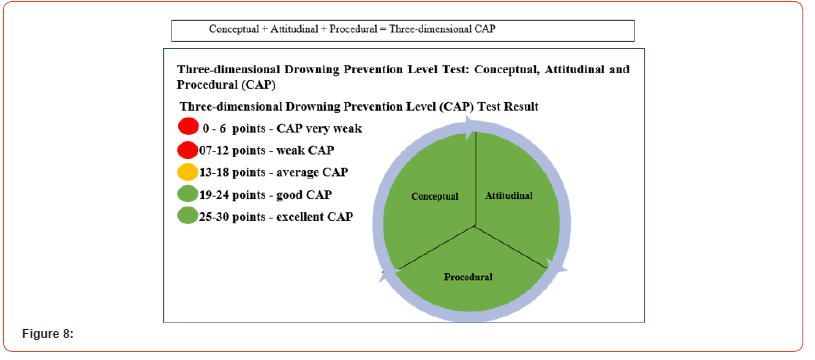

Drowning is a complex public health problem that can be prevented worldwide with strategic educational interventions. Multiple factors can cause drowning, and knowing how to move without putting one’s feet on the ground does not mean that the individual has aquatic skills (procedural content), knows the meaning of a sign/flag (conceptual content), is aware of and behaves in a way that does not put oneself in danger (attitudinal content), can think quickly, and above all, that one knows how to make appropriate decisions when faced with aquatic adversities, such as falling into the deep end, with a current or having cramps. Thus, the objective of this study was to provide an assessment tool that allows the level of threedimensional drowning prevention mastery to be verified in relation to the CAP contents (Conceptual, Attitudinal and Procedural). The professional who uses the CAP test must add the result of each dimension of the tests, which are worth 10 points each. The more correct answers a student gets in all dimensions together, the better their three-dimensional CAP preventive level is. Those who score 0-6 points are considered to have a very weak CAP preventive level; 7-12 points as weak CAP; 13-18 points as average CAP; 19-24 points as good CAP; and finally, 25-30 points as excellent CAP preventive level. It is believed that identifying people’s CAP weaknesses can contribute to the development of more incisive drowning prevention procedures. Using the CAP test to monitor school-age students can help identify safety values, concepts, and skills in certain regions of the country or specific groups that are not familiar with aquatic environments and, thus, help to formulate drowning prevention interventions, if necessary.

Keywords: Drowning, Schoolchildren, Water City, Children and Adolescents

Introduction

Drowning is a complex public health problem, and collaboration across sectors is needed to make an impact and reduce deaths [1]. In recent years, global education could have prevented [2] more than 2.5 million deaths caused by drowning [3]. Researchers from New Zealand, Norway and the United States argue that our attitudes affect our behaviors, and it is our actual behaviors around aquatic environments that will keep us safe or not; they add that it is important to instil respect for water from an early age [4]. This is especially true because the risk of drowning is determined by a complex interaction of individual behaviors, safety knowledge and awareness of hazards [5]. In fact, drowning is caused by multiple factors; Prevention must begin outside the water and be maintained in the water through three-dimensional educational content: conceptual, attitudinal and procedural [6]. Learning to swim (procedural content) is recognized as a drowning prevention strategy [7], however, the debate in recent years includes not only knowing how to move in water. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), swimming can have an educational role in combating drowning when it is taught as a component of a program that has, in addition to content focused on safety skills, understanding (conceptual) and behaviors (attitudinal) in relation to water [8], that is, two other dimensions are also important. Individually, each content dimension can contribute to the prevention of drowning; however, when preventive action encompasses three-dimensional work in which forces come together to prevent death by drowning, the chance of success is greater.

Swimming is much more than crawling from one edge to another. Just as those who want to drive need to learn in three dimensions at driving school, those who are going to swim need to understand that there is practical and theoretical content (procedural, attitudinal and conceptual) that, in addition to being taught/ learned, must be verified to see if the student can perform it correctly [9]. For a driver’s license candidate to be able to drive alone, he or she needs to know how to drive the car on a hill, in a traffic jam, in a parking lot, in a roundabout, with high beams in the face, in a tunnel, at night, in the rain (procedural content). Furthermore, the driver must be aware of the right time to change gears, use the lights (headlights, taillights, turn signals), rearview mirrors, windshield wipers, defroster, give way, drive defensively, interpret signs, adjust the seat, correlate the buttons on the dashboard with their functionality, etc. (attitudinal and conceptual content). Theoretical and practical content come together to have a functionality when applied to the act of driving the car [9]. Similarly, the act of guiding life in the water requires three-dimensional teachings.

Excellent water movement skills (procedural) do not mean that the person is safe from drowning, as they may lack knowledge and attitudes that will save them or prevent them from drowning [6]. Parents and teachers must be aware and cannot falsely assume that if their children know how to swim in a pool, they are “drownproof” [3]. Even if a person can cross a 25m pool without putting their feet on the ground, this does not mean that they have aquatic skills (procedural content), know the meaning of a sign/flag (conceptual content), are aware of and behave in a way that does not put themself in danger (attitudinal content), are able to think quickly, and above all, that they know how to make appropriate decisions when faced with aquatic adversities that they may experience, such as falling into the deep end, with a current or having cramps [9]. The most significant change that occurred in swimming schools was the implementation of “practical swimming” classes in the curriculum, teaching not only procedural content (swimming skill movements), but also conceptual and attitudinal content [6] through the safer swimming methodology [10].

In this context, swimming students need to learn, in addition to procedural content, two new dimensions [11], which are: 1) the attitudinal content dimension, which is the actions focused on teaching the student, so that he/she can be able to respect and/or know how to live with (rules for using the places, teacher’s guidelines, their limits, norms, postures, values, procedures, conduct, prevention habits and attitudes); and 2) the conceptual content dimension which is the actions focused on teaching the student, so that he/she can be able to interpret and/or know about (signs, symbols, warnings, meanings, risks, danger and concepts) [12]. In this sense, it is up to the teacher to select the educational content that needs to be taught so that students do not drown [13] and have preventive awareness [14] to enjoy aquatic places safely throughout their lives [7]. American researchers have emphasized the need to expand knowledge about aquatic safety [15], however, to date, there is no knowledge of a three-dimensional drowning prevention test. What does exist are tests that focus on aquatic (procedural) skills such as aquacity [16] or with the dimensions analyzed separately [11].

The initiative to propose a three-dimensional test for drowning prevention has been under development for decades [17] and meets, above all, the need to alert society to the other two dimensions of prevention (conceptual and attitudinal) to avoid deaths by drowning [18]. Thus, the objectives of this article are a) to alert the population to the need to approach drowning prevention in three dimensions together: conceptual, attitudinal and procedural; b) to provide an assessment instrument that allows verifying the level of three-dimensional drowning prevention mastery in relation to the KAP contents (Conceptual, Attitudinal and Procedural).

Conceptual Content

In the conceptual content dimension, the student learns to “know about” facts, concepts, symbols, images, material principles, such as, for example, what is dangerous? What is shallow/deep and what precautions should be taken in each of these spaces? What is the meaning of the figure or text contained in a certain sign? What is the best place to bathe? Where is it slippery and what are the risks? When to call emergency services. In Brazil, the Mobile Emergency Care Service (SAMU) – 192, or Firefighters – 193. This content can help prevent drowning by working on student awareness (VASCONCELLOS ET AL., 2019) so that they are able to apply aquatic skills if they are in a dangerous situation [19], have emotional control to reason about the best option to follow, know the warning signs, be careful with drains [19] and avoid high-risk behaviors in the aquatic environment.

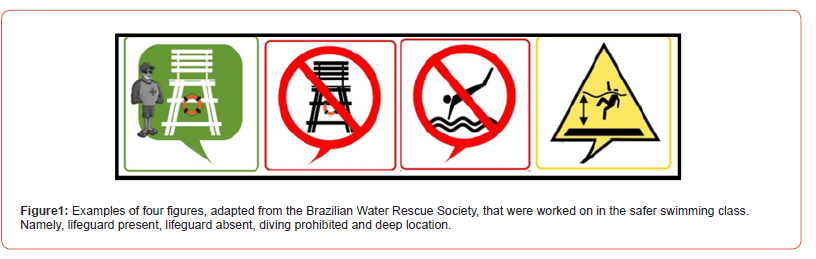

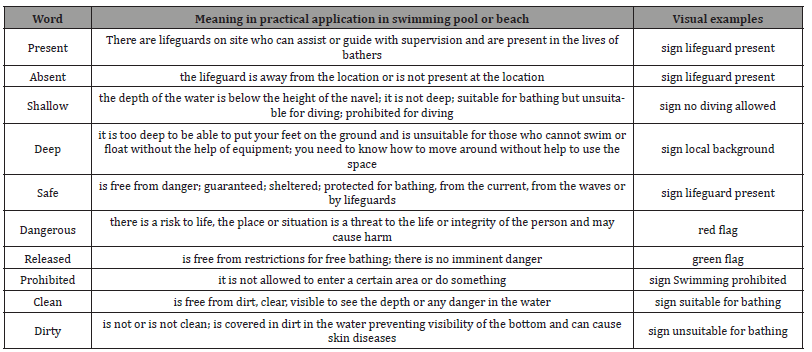

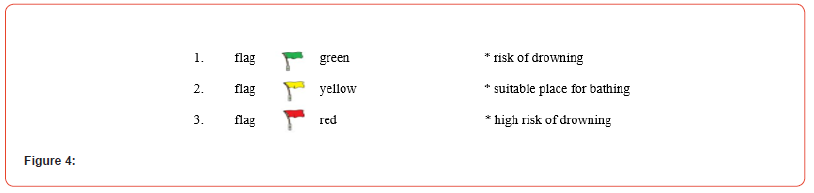

In this sense, it is important to define the concept to be learned to prevent drowning, such as, for example, what to know, what to do in a given situation. Then, later, this concept can be used to determine objectives, choose content and methodology to consolidate it as a concept to be learned by the student. For example, teachers can work on the meaning of the colors of the flags that are displayed on beaches to indicate the current level of danger in the sea, and students can learn to recognize the risk of drowning. A green flag means a suitable place for swimming; a yellow flag means a risk of drowning; a red flag means a high risk of drowning; and a black flag means an area without lifeguards. In the safer swimming methodology, conceptual content is also taught using a memory card game with definitions of conceptual terms [20]. Interventions with students on water safety use conceptual pedagogical content, showing the meaning of the word linked to prevention and its antagonism, such as: prohibited versus permitted; safe versus dangerous; present versus absent; shallow versus deep; clean versus dirty [20].

When this content is taught, students are expected to: learn in class what can and cannot be done; understand the risks and know how to conceptualize and identify: what is dangerous; what is safe; what is shallow/deep and what precautions should be taken in each of these spaces; what is the meaning of the figure or text contained in a certain sign; what is the best place to bathe; know where it is slippery and what the risks are; know when to call emergency services; know the differences between prevention and rescue, know how to identify a lifeguard present or absent [21]. Swimming lessons can develop in their students’ attitudes and values that save lives without putting at risk those who come to help the drowning person [22].

Table 1:of conceptual contents of water safety worked on in swimming classes.

Attitudinal Content

A longitudinal monitoring study conducted with schoolchildren in Rio de Janeiro has focused efforts on teaching attitudinal content, aiming at children and adolescents to learn to “know how to respect and live with” norms, postures, values and attitudes, such as, for example, knowing how to respect the rules for using the aquatic environment and the teacher, adopting habits to prevent drowning and, finally, trying to internalize something that will be carried throughout life [20]. Physical education classes are good for working on these behaviors, rules and discipline, as they have already experienced, since childhood, in sports, the rules of the games, respect for the opponent and, above all, for the referee regarding the acceptance of his decisions [23]. This mediation is important, as among the factors associated with drowning are: problems resulting from lack of awareness, understanding of the dangers of water and increased aquatic risk behaviors [24].

Regarding behaviors related to safer swimming lessons, the results of a recent study [20] showed that, when analyzing older adolescents as a whole, there was a reduction in the number of correct answers among students who responded, for example, that one should swim across a river and enter rough seas just because they are taking swimming lessons. This shows that the student is unable to discern and have an attitude of humility to recognize that, even though they know how to swim in a pool, they do not have the specific skills to swim across a river or enter rough seas, etc. Adolescents overestimate their swimming abilities [25] and require constant attention. It was expected that, the older they are, the greater their ability to interpret texts and answer questionnaires, the more practical experiences, the more teaching and, consequently, the more knowledge they will have about safe behaviors [23], however, this did not happen universally in the school where students have been monitored for 4 years. Adolescents need to have emotional control to decide whether to go into the sea [19], whether they have the necessary skills for that environment, and whether they are in good health to swim [26].

Swimming lessons can help improve aquatic prevention attitudes [11] when they promote teaching about safe behaviors in different aquatic environments [24] and when they do not generate a false sense of security, which can put them at risk when they are, for example, swimming in deep places or with currents [27]. Children and adolescents tend to copy the attitudes of their friends, in this sense, each student has a fundamental role in multiplying values and attitudes to prevent drowning when they are out of school. In fact, the study by Koon et al., 2023, mentions that friends are a primary motivator in childhood and can contribute to prevention. Parents, friends and teachers need to teach, in addition to the correct identification of signs and flags [19], the correct attitudes to be put into practice at a given moment in life when going to a river, pool, beach, dam, waterfall and/or lake. Having attitudes that value prevention and not recklessness/irresponsibility are virtues for safely enjoying the aquatic environment. At the end of each formative assessment in swimming, the teacher needs to check whether there was a change in attitude, whether the student heard about these norms and behaviors in the aquatic environment and put them into practice, that is, whether there was a change in behavior.

Procedural Content Using the Aquacity Test

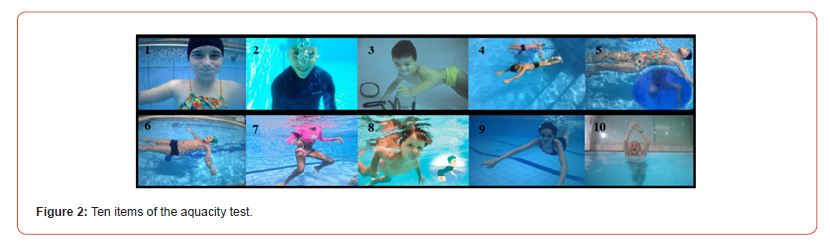

In the procedural content, students learn to “know how to do and execute”, such as the appropriate procedures for each item of the aquacity test [16], in order to improve their aquatic skills. The aquacity test presents the procedural content guidelines that underpin the skills to be mastered by the learner. Using the aquacity test on the first day of class can help identify students who are not adapted to the water environment and direct classes to improve what was identified as a lack of aquatic competence so that they progressively feel more confident and improve their aquacity [6].

The test consists of 10 items that assess the student’s degree of adaptation to the water environment, related to breathing, buoyancy, propulsion, changes between decubitus and palmate positions. Students take the test individually and are evaluated by two teachers, one in and one out of the water. The latter records each item completed. When the student is able to perform the proposed activity alone, for each item, he/she scores one (1) point, and when he/she is unable to do so, he/she is marked (0) for later categorization. The test categorizes the student’s aquacity according to the score obtained, namely, those who achieve from zero to two points as very poor aquacity; from three to four points as poor; from five to six points as average; from seven to eight points as good; and from nine to ten points as excellent aquacity (VASCONCELLOS et al., 2020).

The aquacity diagnosis on the first day of class allows the swimming teacher to work with specific objectives to improve each component of basic aquatic skills (procedural content). The other two contents, conceptual and attitudinal, help to build awareness on how to deal preventively in the aquatic environment [13] and never underestimate the risk and overestimate the ability to swim recklessly in the water [28]. The aquacity test, a tool developed to assess adaptation to the aquatic environment and the progress of students, can be crucial to monitor and improve the performance of beginners in swimming. The use of the test, especially in swimming lessons for children and adolescents, can contribute significantly to improving the monitoring of learning, providing more effective feedback for both students and teachers.

According to Santibánez-Gutiérrez et al. (2022), the safety of children in aquatic environments is crucial and depends on high awareness. However, according to the author, there is a lack of qualitative data on the swimming skills of children and adolescents, and current assessment methodologies are limited, often not considering fundamental skills. Aiming to improve assessment methodologies, the aquacity test was created. The aquacity test is an assessment tool that seeks to identify affinity with the aquatic environment. According to Vasconcellos (2019), this test has been carried out since 2004 and has undergone several updates. Currently, it consists of 10 items, each worth one point when performed correctly, and which are preferably assessed in the first swimming lesson.

Vasconcellos (2022) [29] states that using the aquacity test on the first day of class can help identify students who are not adapted to the aquatic environment and direct classes to improve what was identified as a lack of aquatic competence so that they progressively feel more confident and improve their aquacity. Also, according to the author, the test began to use the Safer Swimming methodology, primarily valuing student safety and familiarization with the aquatic environment before teaching the four swimming styles. Therefore, the current approach to the test assesses skills and actions that may prevent drowning, trauma or situations that impair the learning of the four strokes. The 10 items of the test assess the degree of adaptation of the student to the aquatic environment, related to mastery of breathing, buoyancy, propulsion, changes between lying down and palming [23].

Conceptual Dimension

Conceptual pedagogical content verification test Correlate the meaning of the figures to the text that should be contained on the sign

( ) No pushing

( ) Deep location

( ) No diving

( ) Lifeguard absent

( ) Emergency telephone number

( ) Lifeguard present

( ) No swimming

Match the columns to the meaning of the flags.

The following is the answer key for the conceptual part. In item 1.1, correlate the answers: (3) no pushing; (6) deep place; (4) no diving; (1) no lifeguard; (2) emergency telephone number; (7) lifeguard present; and (5) no swimming. In item 1.2, connect the columns, the answers are: 1. green flag - place suitable for bathing; 2. yellow flag - risk of drowning; and 3. red flag - high risk of drowning.

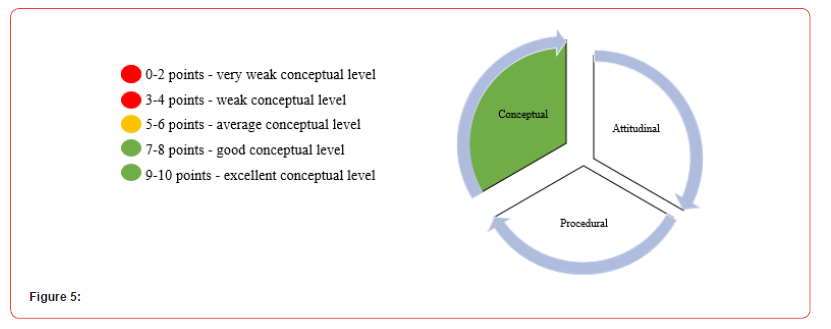

The result of the conceptual knowledge level is the sum of each correct answer (1 point) obtained in items 1.1 and 1.2.

Attitudinal Dimension

Test to verify attitudinal pedagogical content

Regarding swimming lessons. Answer Yes or No

1. Should I play at pushing other students into the water? ( ) Yes

( ) No

2. Should I put my hand in the hole that sucks water out of the

pool? ( ) Yes ( ) No

3. Should I wait for the teacher to call me to get in the pool? ( )

Yes ( ) No

4. Should I ask or tell the teacher when I’m going to get out of the

pool? ( ) Yes ( ) No

5. Should I avoid accidents in the pool and value prevention actions?

( ) Yes ( ) No

6. Should I enter the pool by doing a somersault? ( ) Yes ( ) No

7. Should I play near the drain at the bottom of the pool? ( ) Yes

( ) No

8. Should I play racing in the wet area around the pool? ( ) Yes

( ) No

9. Should I try to swim across the river because I take swimming

lessons? ( ) Yes ( ) No

10. Should I go into the rough sea because I take swimming lessons?

( ) Yes ( ) No

Below is the answer key for the attitudinal part. In item 2.1: Answer Yes (Y) or No (N). The correct answers are: 1(N); 2(N); 3(S); 4(S); 5(S); 6(N); 7(N); 8(N); 9(N); 10(N)

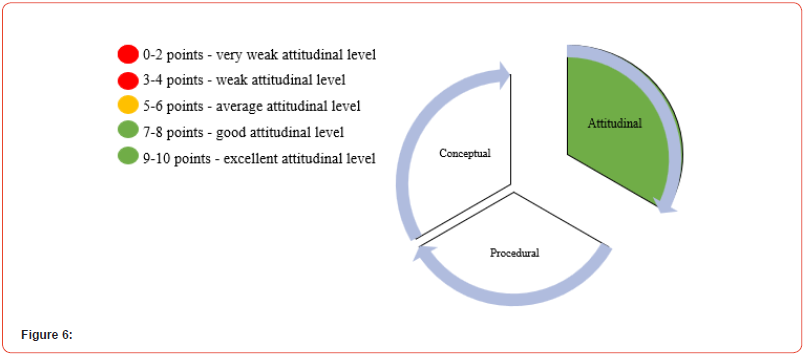

The result of attitudinal knowledge is the sum of each correct answer obtained in items 2.

Procedural or Aquacity Dimension

Test to verify procedural pedagogical content

Can you perform the activity to be tested?

1. Perform (static apnea) breathing blocks underwater - 10 seconds

- repeat 3 times

2. Submerge your head in the water without fear, exhale (breathing

control) - 5 times

3. Sink and pick up an object from the bottom without using goggles

- 1 object at a depth of 1 meter

4. Change from dorsal to ventral decubitus - 2 times

5. Change from vertical to horizontal position without placing

your foot on the ground - 2 times

6. Float in dorsal decubitus without the aid of materials - 30 seconds

7. Hold yourself upright using your palms - 30 seconds

8. Use all four limbs as propulsive segments on the surface to the

edge “doggy style” - 3 meters

9. Perform underwater movement (dynamic apnea) - 2 meters

10. Squat, sink while standing and jump with your hands out of the

water - 2 times - 2 meters

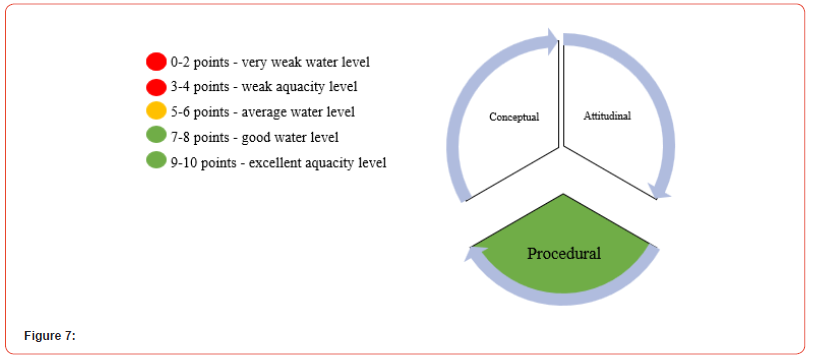

Aquacity level result of the procedural test is the sum of each correct answer (1 point) obtained in the 10 activities tested.

Union of Dimensions to form the Three-Dimensional CAP Test

The use of the test in the conceptual dimension allows us to identify, in isolation, as a form of preventive diagnosis, what the student has learned in relation to “knowing about”, facts, concepts, symbols and images. The isolated assessment in the attitudinal dimension allows us to verify the learning in relation to “knowing how to respect and live with” norms, postures, values and attitudes. Finally, in the procedural dimension, it allows us to identify the level of aquacity on the first day of class, as well as increasingly making the student’s progress in swimming something measurable, tangible and objective. Researchers from Australia highlight the importance of acquiring awareness, knowledge and skills in water safety, and how this can influence attitudes and manage behaviors in relation to the risk of drowning [1]. To this end, these swimming students need to be assessed in three dimensions to verify whether they have acquired conceptual knowledge and developed correct attitudes regarding the risks of drowning, learned to have emotional control and discernment in dangerous situations, know how to use their arms and legs efficiently for support and movement, mastered aquatic breathing, vertical and horizontal floating, changes in position and can move for a few seconds in search of a safe place.

To assess the level of drowning prevention in the three dimensions together, a unification was developed to form the three-dimensional CAP test. The professional who is going to use the CAP test must add the result of each dimension of the tests that are worth 10 points each, as shown below. Afterwards, they must compare it with the CAP result table below. The more correct answers the student has in all dimensions together, the better their three-dimensional CAP drowning prevention level. Those who obtain 0-6 points are considered to have a very weak CAP prevention level; those who obtain 0-12 points as weak CAP; those who obtain 13-18 points as medium CAP; from 19-24 points as good CAP and finally, from 25-30 points as excellent preventive CAP level.

Use of the Three-Dimensional CAP Test

This instrument for assessing the level of drowning prevention can be used in a fragmented manner, with analysis of each dimension, for example, only the conceptual part, only the attitudinal part or only the procedural part. Another way of using the instrument is to assess two dimensions at the same time with the combinations that the evaluator finds most relevant to the target audience. Finally, the most complete form of the instrument is to use it to assess the individual in a three-dimensional manner, where information on the contents: conceptual, attitudinal and procedural will be recorded for planning swimming lessons focused on the student’s preventive awareness [30].

Final Considerations

The three-dimensional CAP preventive drowning level test is another tool that can help identify drowning risks, especially in children and adolescents with CAP levels categorized as very weak and weak. A diagnostic assessment using the CAP should be done before starting a swimming lesson program. It can be done on the first day of class together with the aquacity test to identify what the student already knows about concepts and symbols, how he interacts with rules and values, what he can do, so that the teacher can direct him to the class of the same level, develop a personalized strategy and, above all, be able to prevent drownings. Using the CAP test to monitor school-age students can help identify values, concepts and safety skills in certain regions of the country or specific groups that are not familiar with aquatic environments and, thus, help to formulate preventive interventions, if necessary.

Acknowledgement

None.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest.

References

- Willcox-Pidgeon S, Franklin RC, Devine S (2025) Drowning prevention strategies for migrant adults in Australia: a qualitative multiple case study. BMC Public Health 25(1): 1911.

- Alqahtani A, Alsubai S, Sha M, Peter V, Almadhor AS, et al. (2022) Falling and Drowning Detection Framework Using Smartphone Sensors. Comput Intell Neurosci: 6468870.

- Van DT, Cocker K, Seifert L, Button C (2022) Assessment of water safety competencies: Benefits and caveats of testing in open water. Front Psychol 13: 982480.

- Stallman RK, Moran K, Quan L, Langendorfer S (2017) From Swimming Skill to Water Competence: Towards a More Inclusive Drowning Prevention Future. International Journal of Aquatic Research and Education (10)2: 1-35.

- Pratt EG, Peden AE, Lawes JC (2025) Far From Help: Exploring the Influence of Regional and Remote Residence on Coastal Visitation and Participation, Risk Perception and Safety Knowledge and Practices. Aust J Rural Health 33(1): e70018.

- Vasconcellos MB, Macedo FC (2021) Prevenção do afogamento com uso de conteúdos: Atitudinal, procedimental e conceitual. Latin American Journal of Development, Curitiba 3(6): 3741-3754.

- Peden AE, Franklin RC (2020) Learning to Swim: An Exploration of Negative Prior Aquatic Experiences among Children. Int J Environ Res Public Health 17(10): 3557.

- WHO (2017) Preventing drowning: an implementation guide. Geneva: World Health Organization.

- Vasconcellos MB (2025) Matricule-se na autoescola para aprender a nadar. Revista Empresário Fitness & Health. Edição 149. Maio de.

- Vasconcellos MB (2015) Natação + Segura. Revista empresário Fitness & Health 13(74): 28-29.

- Vasconcellos MB, Blant GO (2024) Relato de participação de criança autista na aula de natação com metodologia Natação + Segura. Revista Carioca de Educação Física 19(1): 37-46.

- Vasconcellos MB (2025) Aula de natação que ensina a reconhecer um afogamento. Revista Empresário Fitness & Health. Edição 147.

- Vasconcellos MB, Michel CC (2025) Aplicação da metodologia Natação + Segura em adolescente com síndrome de Down. Nadar! Swim Mag 5(168): e168-e105.

- Vasconcellos MB, Macedo FC, Silva CCC, Blant GO, Sobral IMS, et al. (2023) Segurança aquática se aprende na escola: Acompanhamento do nível de Conhecimento Preventivo de Afogamento dos escolares do Rio de Janeiro, Brasil. Revista Brasileira de Medicina de excelência 1(2): 30-55.

- Playter K, Hurley E, Lavin-Parsons K, Parida K, Ballinger Z, et al. (2024). Water safe Worcester: student-led drowning prevention in an adolescent underserved population. Front Public Health 12: 1387094.

- Vasconcellos MB, Szpilman D, Queiroga AC, Mello D (2017) Swim + Safe: test for diagnostic evaluation and monitoring of water skills of beginner students. World conference on drowning prevention. Canada: Vancouver.

- Vasconcellos MB, Santos RO (2004) Um estudo sobre o auto-salvamento nas aulas de natação, para crianças de 4 a 6 anos, como conteúdo auxiliar na prevenção de afogamentos. Revista Sprint 21(134): 43-47.

- Vasconcellos MB, Caloiero S (2025) Use of the aquacity test as a tool for analyzing the level of beginner swimming students. Aracê 7(5): 21057-21079.

- Gupta M, Rahman A, Baset K, Ivers R, Zwi AB, et al. (2019) Complexity in Implementing Community Drowning Reduction Programs in Southern Bangladesh: A Process Evaluation Protocol. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 16(6): 968.

- Vasconcellos MB, Blant GO, Michel CC, Diogo EVF (2025) Longitudinal monitoring in the 2022-25 quadrennium of the Drowning Prevention Knowledge Level (DPKL) of schoolchildren in rio de janeiro, brazil. Aracê 7(3): 15531-15559.

- Vasconcellos MB (2023) Conceitos de segurança aquática podem salvar vidas. Revista Empresário Fitness & Health., Juiz de For a pp: 1 - 10.

- Vasconcellos MB (2025) Swimming Lesson Teaching How to Provide Buoyancy. Res Inves Sports Med 11(2): 1067-1069.

- Vasconcellos MB, Corrêa PR, Blant GO, Viana LCA, Michel CC, et al. (2024) Longitudinal study of the Drowning Prevention Knowledge Level of schoolchildren in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. International Seven Journal of Health Research 3(2): 761-783.

- Ekanayaka J, Geok CK, Matthews B, Dharmaratne SD (2021) Influence of a Survival Swimming Training Programme on Water Safety Knowledge, Attitudes and Skills: A Randomized Controlled Trial among Young Adults in Sri Lanka. Int J Environ Res Public Health 18(21): 11428.

- Dimmer A, Proulx KR, Guadagno E, Gagné M, Perron PA, et al. (2025) Beneath the Surface: A Retrospective Analysis of Pediatric Drowning Trends & Risk Factors in Quebec. J Pediatr Surg 60(4): 162184.

- Işın A, Peden AE (2024) The burden, risk factors and prevention strategies for drowning in Türkiye: a systematic literature review. BMC Public Health 24(1): 528.

- Williams SR, Dow EA, Johnson MB (2023) Drowning is fast, silent, and preventable: a Texas example of research in action. Inj Epidemiol 10(Suppl 1): 64.

- Davis CA, Lareau S (2024) Drowning. Emerg Med Clin North Am 42(3): 541-550.

- Vasconcellos MB, Macedo FC, Silva CCC, Blant GO, Sobral IMS, et al. (2022) Segurança aquática: teste de conhecimento preventivo de afogamento usado nas aulas de natação para prevenir o afogamento. Brazilian Journal of Health Review 5(6): 24304-24324.

- Vasconcellos MB (2013) Avaliação na Natação-Teste de Aquacidade. 8º Congresso carioca de Educação Física. Rio de Janeiro.

-

Marcelo Barros de Vasconcellos*. Swimming Safer: Three-Dimensional Drowning Prevention Level Test: Conceptual, Attitudinal and Procedural (CAP). Aca J Spo Sci & Med. 2(5): 2025. AJSSM.MS.ID.000551.

-

Water City, Drowning, Swimming, Conceptual Content, Three-Dimensional, Schoolchildren

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.