Research Article

Research Article

Professional and Amateur Athletes’ Use and Knowledge About the Adverse Consequences of Performance Enhancing Drugs

Daniel Herstain1,2, Isak Elkayam2 and Einat Peles2-4*

1lsrael National Anti-Doping Agency

2School of Medicine, Faculty of Medical and Health Sciences, Tel Aviv University, Tel Aviv, Israel

3Dr. Miriam and Sheldon G. Adelson Clinic for Drug Abuse, Treatment and Research, Tel Aviv Sourasky Medical Center, Tel Aviv, Israel

4Sagol School of Neuroscience, Tel Aviv University, Tel Aviv, Israel

Einat Peles, School of Medicine, Faculty of medical and health sciences and Sagol School of Neuroscience, Tel Aviv University, Israel

Received Date:April 17, 2024; Published Date:April 26, 2024

Background: Some athletes use Performance-Enhancing Drugs (PEDs) to improve their performance. These substances can have severe side

effects, potentially harming the athlete’s health in the short or long term and in some cases, leading to death. The use of these substances is often

clandestine and lacks proper medical supervision. The consequences of such use are not well understood by athletes, and greater awareness could

prevent hazardous usage.

Research Objectives: This study aimed to assess the level of knowledge about the consequences of using various widely used performanceenhancing

substances among elite and amateur athletes.

Research Methods: We conducted a cross-sectional survey using an anonymous online questionnaire. Participants included members of the

Israeli Olympic team, professional athletes from various sports, and amateurs who regularly train in diverse sports. We compared the knowledge

levels across these groups.

Results: A total of 452 athletes, consisting of 125 professionals and 327 amateurs, completed the questionnaire. The average knowledge scores

were 46.0 ± 17.5 for professionals and 50.8 ± 17.7 for amateurs. Adjustments for age, education, and gender differences revealed no significant

discrepancies in scores between groups. A higher level of education and older age were associated with better knowledge scores. Only 35% of

respondents had previously received training on prohibited substances, and those who had trained scored higher in both groups, although the scores

remained inadequate.

Conclusions: Contrary to expectations, most athletes are unaware of the risks associated with PED use. Our findings suggest that updating and

enhancing educational programs through the national doping prevention agency could mitigate the consumption of dangerous substances and

prevent associated health risks.

Keywords:Performance Enhancing Drugs (PEDs), Drugs in Sports, PEDs awareness and attitude, PEDs knowledge

Introduction

The use of performance-enhancing drugs (PEDs) is widespread among professional and amateur athletes across numerous sports. A meta-analysis published in the Journal of Sports Medicine and Physical Fitness indicates that PED usage rates are about 3-5% among children under 18 and 5-15% among adults, although actual figures for adults may be as high as 15-25% [1]. Analysis of 7,289 blood tests from 2,737 elite track and field athletes revealed a 14% increase in detections from 2001 to 2011 [2]. These substances, which include various unauthorized drugs and banned performance methods, pose significant health risks. PEDs are classified into three categories: prohibited at all times, prohibited in-competition, and prohibited in specific sports, with each category subdivided into specific substances as defined by the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) [3]. A substance or method is banned if it enhances performance, harms the athlete’s health, or violates the spirit of the sport.

Prohibited substances include anabolic agents, hormones, peptides, growth factors, beta-2 agonists, metabolic modulators, masking agents, stimulants, narcotics, cannabinoids, and glucocorticoids, all known for their potential health risks [4,5]. Illegal practices such as blood doping and gene doping are also prohibited due to their health implications [5]. Recent studies have focused on both the physiological and psychological impacts of doping, exploring detection methods and understanding why athletes use these substances, aiming to develop effective educational and preventive measures [6,7,8]. Research suggests that the lack of objective data on PEDs means that availability and awareness are key predictors of use among athletes unfamiliar with the risks [9,10-14]. This highlights the urgent need for improved educational programs [6].

There is a scarcity of research on athletes’ awareness of PED risks, often due to accessibility issues and reluctance to participate in studies, even anonymously [8]. Enhancing understanding of these risks could help develop more effective education strategies [9]. The Israel National Anti-Doping Agency is committed to upholding the integrity of sports through adherence to the rules and spirit of competition [8,9]. This study aims to assess the awareness and knowledge of Israeli amateur and professional athletes regarding the risks associated with PED use. We anticipate a general lack of awareness, particularly among amateurs, influenced by age and experience, with greater familiarity expected with street drugs than with PEDs.

Materials and Methods

Participants:

The research was carried out in Samsun (2022-2023). 42 Hearing-impaired male sportsmen aged 19-22, operating in deaf sports clubs, participated in the study voluntarily.

Research design and model:

Pre-test, post-test, and control group models from experimental models were used in the research design. After the first measurements, the subjects were randomly assigned to one of the three groups. (A) Experimental group, (n=14). Aged (20.86±1.23), years, height, (178.71±1.58) cm. Body weight, (69.98±7.28) kg., training age, (4.50±1.56). (B) Experimental group, (n=14). Aged (20.57±1.40) years, height, (179.21±4.56) cm. Body weight, (69.46 ±7.55) kg., training age, (4.36 ±1.65). (C) Control group (n=14). Age, (20.78 ±1.58) years, height,(178.14± 6.57) cm., Body weight, (70.86 ±11.96) kg., training age, (4.57±2.10). While the athletes were in the general preparation period and continuing their training in their clubs, (Anaerobic training: Group A (speed+strength) training; Group B: Plyometric training. Aerobic trainings: A and B research groups together) training programs were applied to the experimental groups for 8 weeks, the content of which was determined beforehand. Two measurements were taken at the beginning and end of the study.

Methods

This study received approval from the Helsinki Committee of the Tel-Aviv Sourasky Medical Center and was conducted in cooperation with the Olympic Committee in Israel.

Participants

Participants included professional athletes from the Israeli Olympic squad and amateur athletes found on different online Israeli forums and social media groups.

Questionnaire

The anonymous questionnaire (Appendix) was designed by one of the authors and approved by a member of the Israeli National Committee for Drug Prevention in Sports who is an expert in sport physiology. The first part of the questionnaire included 17 questions on knowledge about PEDs. Each question was worth 6 points and the final score ranged from 0 to 102, with a score of over 60 considered a passing grade. The validity of the test (face validity) was based on the fact that it involved all prohibited drug groups that are used by athletes, as recognized by the Israeli National Committee for Drug Prevention in Sports and based on the WADA criteria [3]. The questionnaire was passed on to a wider group of experts (members of the administration of the national agency for drug prevention in sports) and to medical students, and non-expert non-selective individuals. The second part of the questionnaire included several subjective questions about the behavior and the viewpoint of the athlete with regard to PEDs and demographic questions, such as whether the responder was a professional or amateur athlete, age, sex, education, years in the sport, and the type of sport. The internal reliability of the first part of the questionnaire was calculated by checking the connection between overall score and the individual score for each question.

Methodology

The questionnaire was sent via email to be filled anonymously on the internet (without any identifying information of the athlete except for age and the branch of sport) to all members of the broad Israeli Olympic squad (about 100 athletes) between February 2017 and September 2017 and on social media groups and forums of amateur athletes.

Statistical analyses

The amateur and professional groups were compared by means of the ANOVA test for continuous variables and the chi-square test with categorical variables. The knowledge score of the amateur and professional groups, including each of the variables that significantly differed between the groups in univariate analyses (p < 0.05), were compared with ANOVA multivariate analyses.

Results

Characteristics of the athlete groups:

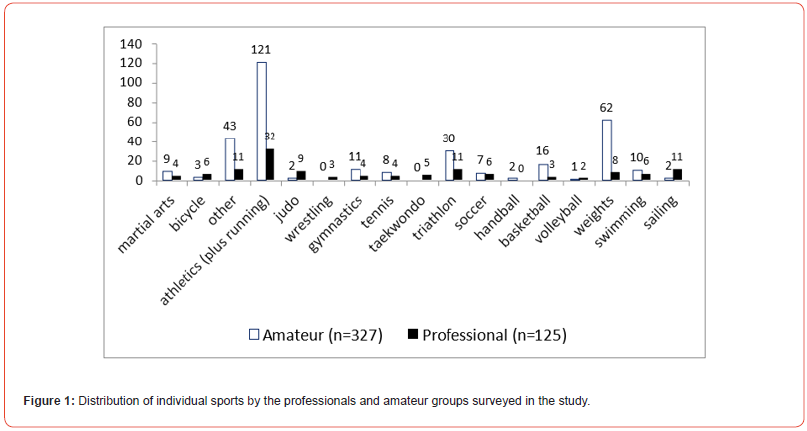

A total of 452 participants consisting of 125 professional and 327 amateur athletes were enrolled in this study. The amateur group was comprised mainly of those whose sports were running long distances (n = 121), weightlifting (n = 62), and triathlon participants (30). The professional group was comprised mainly of individuals whose sports were athletics (including running) (n = 32), triathlons (n = 11), and sailing (n = 11) (Figure 1).

Figure 1:Distribution of individual sports by the professionals and amateur groups surveyed in the study.

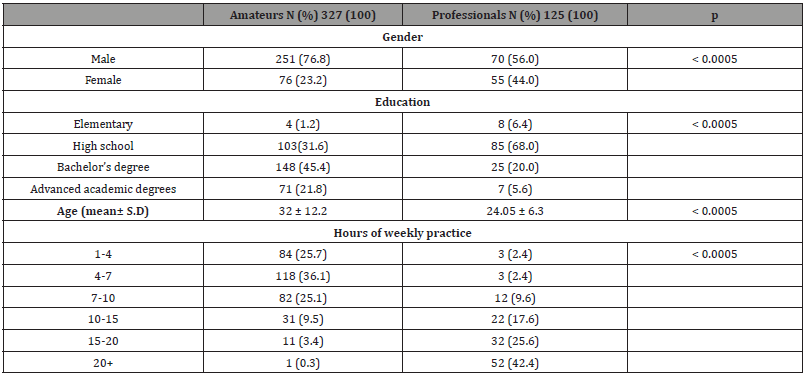

A comparison of the sociodemographic variables between the two groups is presented in (Table 1). The professional group included more females (44% vs. 23.2% for the amateurs), their mean age was younger (24.1 ± 6.3 vs. 32 ± 12.2 years) and had fewer years of education (p < 0.0005). The groups also differed by intensity of practice, with most of the professionals claiming to practice 20 hours of more per week (42.4%) compared to the majority of amateurs who reported training 4-7 hours per week.

Table 1:Comparing sociodemographic variables between professional and amateur athletes.

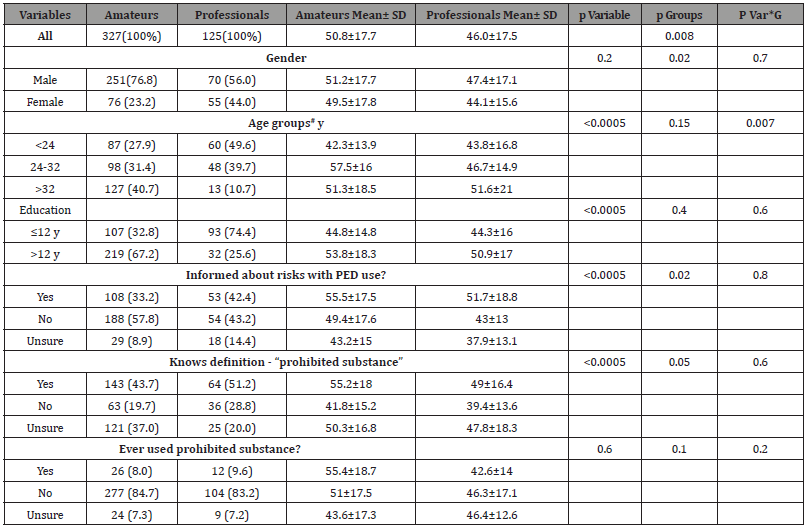

Knowledge score (Table 2):

The amateurs had a higher knowledge score (50.8 ± 17.7) compared to the professionals (46.0 ± 17.5, p = 0.008). The knowledge score differed between groups, independent of gender (0.02), with no differences between genders (0.2). However, when the knowledge score stratified into age groups, the differences between the groups disappeared (p = 0.15), but age groups differed significantly (p < 0.0005) with an interaction effect (p = 0.007): specifically, the score was associated with age for the amateur group, while the age group of 24-32 years had the highest knowledge score for the professional group. When the knowledge score was stratified according to the subgroup of education level, the difference in the knowledge score between the amateurs and professionals disappeared (p = 0.4), while there was a significant association between education and knowledge score in both groups (p < 0.0005) (Table 2).

Table 2:Comparison of knowledge scores of selected variables between professional and amateur athletes.

ANOVA, p Var*G (interaction between amateurs and professionals’ groups and variable (i.e. gender, age groups)). #Age was unknown for 15 amateurs and 4 professional subjects.

When comparing mean knowledge score by the participants response (yes, no, unsure) to the question of receiving information regarding prohibited substances, the amateurs knowledge score was significantly higher than the professional independent of the response (p=0.02), and in both groups, a higher scores associated to the individuals that received more information regarding performance enhancing drugs, and the lower grades were associated to those that reported not receiving such information (p<0.0005). When comparing the knowledge score based on the response to the question “do you know the definition of a prohibited substance”, the difference remains between the professionals and amateurs (p=0.05), and the response in both groups, had a direct association to the grade in a way that those responding positively received a higher score in the knowledge test (p<0.0005). When comparing knowledge score based on the answers to the question “did you ever use a prohibited substance”, there is no relation between the response and the knowledge score, and that the difference between amateurs and professionals disappeared as well “The score of the amateurs to the question of ever having received knowledge about PEDS was significantly higher than that of the professionals…..”

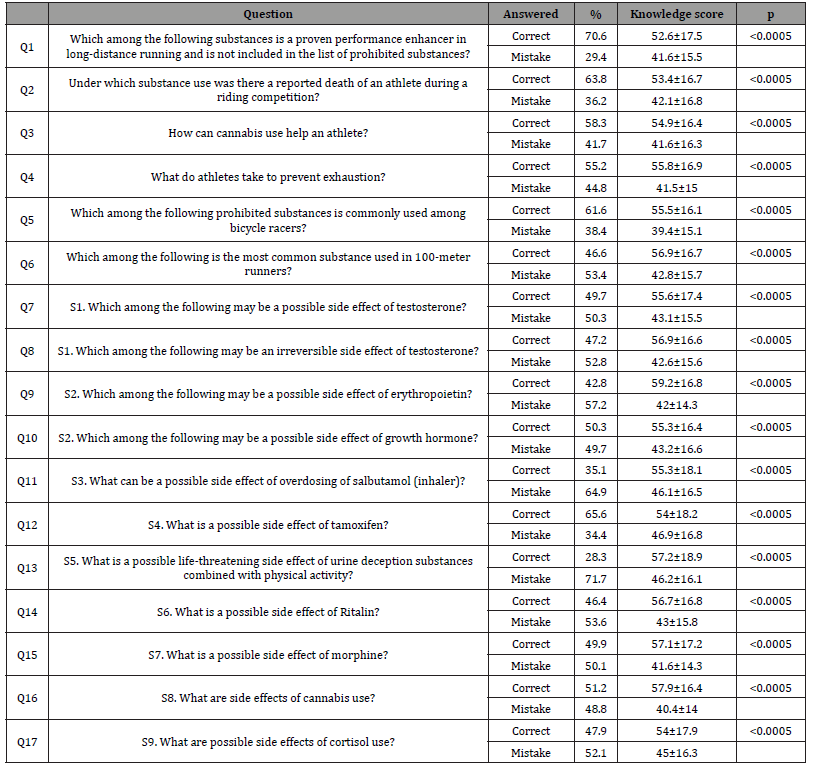

Distribution of responses to questions requiring knowledge (Table 3):

More than half of the participants did not know the answer to 9 out of 11 knowledge-based questions on possible side effects of PEDs (questions 6-9, 11, 13-15, 17). For example, 50% of the subjects were not familiar with the possible side effects of anabolic steroids (questions 6-7), which are the most widespread substances in current use. In contrast, more than 50% of individuals correctly answered 5 out of the 6 questions that covered general knowledge of doping, (questions 1-6). For example, over 50% of the participants correctly answered the two questions on cannabis (questions 2 and 16). Most of them, however, did not know that the side effects of PEDs were life-threatening (questions 13 and 15), and that 36% of them did not know that there were reported deaths of athletes that consumed stimulants (question 2). The mean score for each question was significantly higher (p < 0.0005) between those that replied correctly compared to those who got a question incorrect on each of the 17 questions (Table 3).

Table 3:Distribution of responses and relation to knowledge score.

Discussion

In alignment with our hypotheses, this study confirms a significant gap in athletes’ understanding of PED side effects. The survey revealed that 8.4% of respondents admitted using prohibited substances, which contrasts with historical data suggesting a usage rate of 15-25% [1]. Additionally, random testing by the Israel National Anti-Doping Agency showed that the detection rate in Israel (0.9%) aligns closely with global figures (approximately 1%) as per WADA standards [3]. Despite a higher average knowledge score among amateurs (50.8) compared to professionals (46), both scores fall below the proficiency threshold of 60, indicating widespread ignorance. The analysis also highlighted that age and education significantly influence knowledge scores, yet these factors balance out, showing no overall difference between amateur and professional groups when controlled. Notably, older professionals tended to score higher, suggesting increased awareness with age, while competitive pressures lessened. Education level directly correlated with knowledge, underscoring the role of intellectual resources in understanding PED risks.

Only 35% of participants had previously received formal education on PEDs, yet even among these individuals, knowledge scores remained disappointingly low. This points to the educational interventions’ inadequacy rather than their total absence. Interestingly, participants who knew the definition of a prohibited substance scored higher, though their overall knowledge was still insufficient for understanding the associated risks. Given that only a small fraction of respondents admitted to PED use, and many may have withheld their true usage habits due to the survey’s sensitive nature, the actual prevalence of PED use could be underestimated. This underreporting highlights the critical need for enhanced educational programs that not only address the definition but also the detailed consequences of PED use. Our findings indicate that current educational efforts are not sufficient to significantly impact athletes’ understanding of PEDs, suggesting an urgent need for enhanced educational strategies.

Limitations

We believe that we may face Information-Bias and Selection- Bias due to the nature of the questionnaire, and even though it is anonymous, some athletes might fear to participate or reveal the truth about using performance enhancement drugs.

Conclusion

The use of PEDs continues to represent a serious source of worry that has been expanding in recent years.

The Israel National Anti-Doping Agency is responsible for preventing the phenomenon of drug use by athletes and promote clean sports. In addition, it is the job of the agency to educate athletes. Using the values and conclusions collected in this study, it will be possible to create a new education program. This will allow adding more components necessary and important for preventing the phenomenon of drug use in sports and prevent damages and risks to the health of athletes posed by using PEDs.

Acknowledgement

None.

Conflict of interest

No Conflict of Interest.

References

- Laure E (1997) Epidemiologic approach of doping in sport. A review. J Sports Med Phys Fitness 37(3): 218-224.

- Sottas PE, Robinson N, Fischetto G, Dolle G, Alonso JM, et al. (2011) Prevalence of blood doping in samples collected from elite track and field athletes. Clin Chem 57(5): 762-769.

- (2016) WADA List of Prohibited Substances and Methods.

- Bird SR, Goebel C, Burke LM, Greaves RF (2016) Doping in sport and exercise: anabolic, ergogenic, health and clinical issues. Ann Clin Biochem 53: 196-221.

- Peters C, Schulz T, Michna H (2024) Biomedical Side Effects of Doping project of the European Union.

- Bahrke MS, Yesalis CE (2002) Performance enhancing substances in sport and exercise. Champaign: Human Kinetics.

- Gucciardi DF, Jalleh G, Donovan RJ (2011) An examination of the Sport Drug Control Model with elite Australian athletes. J Sci Med Sport 14(6): 469-476.

- Backhouse S, McKenna J, Robinson S (2007) Attitudes, behaviours, knowledge and education - drugs in sport: past present and future [online]. Canada: World Anti-Doping Agency 2007.

- Petroczi A, Aidman E (2009) Measuring explicit attitude toward doping: review of the psychometric properties of the Performance Enhancement Attitude Scale. Psychol Sport Exer 10(3): 390-396.

- Dodge T, Jaccard JJ (2008) Is abstinence an alternative? Predicting adolescent athletes’ intentions to use performance enhancing substances. J Health Psychol 13(5): 703-711.

- Donovan RJ, Egger G, Kapernick V, John Mendoza (2002) A conceptual framework for achieving performance enhancing drug compliance in sport. Sports Med 32(4): 269-284.

- Fabio Lucidi, Arnaldo Zelli, Luca Mallia, Caterina Grano, Paolo M Russo, et al. (2008) The social-cognitive mechanisms regulating adolescents’ use of doping substances. J Sports Sci 26(5): 447-456.

- Strelan P, Boeckmann RJ (2003) A new model for understanding performance enhancing drug use by elite athletes. J Appl Sport 15(2): 176-183.

- Bloodworth AJ, McNamee M (2010) Clean Olympians? Doping and anti-doping: the views of talented young British athletes. Int J Drug Policy 21(4): 276-282.

- (2009) WADA World anti-doping agency: Education.

- (2021) WADA World Anti-Doping code.

- (2016) WADA Anti-Doping Testing Figures.

-

Daniel Herstain, Isak Elkayam and Einat Peles*. Professional and Amateur Athletes’ Use and Knowledge About the Adverse Consequences of Performance Enhancing Drugs. Aca J Spo Sci & Med. 2(1): 2024. AJSSM.MS.ID.000526.

-

Amateur Athletes', PEDs Knowledge, Drugs in Sports, Health Risk Awareness, Performance Enhancing Drugs (PEDs), Dangerous Health Risk, PEDs Awareness and Attitude

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Materials and Methods

- The Basic Tools of Scientific Inquiry

- Literature Review

- Theoretical Framework

- Research Design

- Findings and Discussion

- Conclusion and Recommendations

- Based on the findings, the following recommendations are considered:

- Declaration Statements

- Funding

- Data Availability Statement (DAS)

- Compliance with Ethical Standards

- Acknowledgement

- Conflict of Interest

- References