Research Article

Research Article

Exploring the Dosage of Handwriting Curricula Among School-Aged Children

Bryan Gee*, Kimberly Lloyd and Jane Ewoniuk

Department of Occupational Therapy, Rocky Mountain University of Health Professions, USA

MBryan Gee, Department of Occupational Therapy, Rocky Mountain University of Health Professions

Received Date:March 31, 2025; Published Date:April 21, 2025

Abstract

Handwriting is an essential activity for elementary-aged students, and the use of a handwriting curriculum is often spurred by educators with support from specialists and utilized as an intervention for struggling students or classrooms. This study aimed to explore the frequency, intensity, and duration of published peer-reviewed outcome studies focused on formal handwriting curriculums used among pediatric populations. Using a content analysis approach, the authors evaluated the dosage parameters of 24 peer-reviewed articles. The findings revealed that the studies that used formal handwriting curricula had dosage parameters for the categories of the number of weeks (M=13.01, SD = 8.77), the number of minutes per session (M= 33.61, SD = 33.89), sessions per week (M=3.02, SD = 1.12), and total intervention hours (M=92.96, SD = 367.33). This study provides novel information about the dosage of handwriting curricula and is meaningful to occupational therapy professionals working among pediatric populations.

Keywords:Handwriting; Penmanship, School age; Curriculum

Introduction

Handwriting is “the process of forming letters, figures, and other significant symbols, predominantly on paper” [1]. Further, handwriting has been described as written communication or script done by hand with a tool, whether a pen, pencil, or digital stylus (Dictionary, n.d.). For the purpose of this article, this includes manuscript (print) and cursive. However, this definition does not provide a robust understanding of the complexity of this essential student activity. Handwriting involves metacognitive and linguistic interplay and physical coordination [2,3]. Handwriting is one of the most ubiquitous activities of elementary-aged students, yet no national standards surrounding its instruction or implementation in school systems exists. Even in the digital age, handwriting is an important activity that is the basis for much of a student’s academic work. With the advances of computers, tablets, and smartphones, children’s earliest exposure may be digital before they have access to prewriting and writing utensils [4].

Historically, fine motor skills for academic work involved direct handwriting instruction and activities like cutting and coloring. Children (ages 6-12 years) spend 31-60% of their time on fine motor or writing tasks, with 42% on paper-pencil tasks [5,6]. Recent estimates indicate that 18-47% of classroom time focuses on fine motor skills, 84% of which is devoted to handwriting [7].

The earlier a school-aged student learns to write with fluency and speed, the less likely future academic difficulties will arise [8,9]. Additionally, it has been reported that young people with more advanced fine motor skills demonstrate higher academic performance and earlier reading development [10]. Suggate, et al. [11], reported that early fine motor skills are subtly linked to reading achievement in elementary school. Thus, handwriting is and continues to be a solid foundational activity for students in their academic roles.

In the school setting, handwriting is taught within literacy, which encompasses reading, writing, and comprehension of written communication [12]. When a child writes, the outcome measure is not the handwritten quality per se. Still, students can understand, evaluate, utilize, and engage with the written text to participate in society, achieve goals, and develop their knowledge and potential (Statistics, n.d.).

The handwritten work also requires the ability to be read and comprehended by the intended audience. When students have difficulties with handwriting, factors such as legibility, spacing, and organization of their writing may impact the evaluation of the outcome measure [12-14]. Students whose work is difficult to read are often given poorer grades despite understanding and comprehending the information. Thus, handwriting difficulties can continue to negatively impact a student’s academic performance and, subsequently, their self-esteem and motivation [15]. Primary teachers provide the most significant increments of exposure to modeled instruction and practice, decreasing time for explicit instruction from 3rd to 5th grade when writing becomes automatic [9,16,17]. However, handwriting practice can often produce improved results well into a student’s secondary education setting [3]. For students who struggle with handwriting, continued direct instruction and practice can have a lasting impact beyond the kindergarten - 6th grade years [13,18].

Even with explicit instruction, handwriting is a complex and challenging activity to learn and master. Students must also organize their thoughts, copy from near and far points in space, and attend for sustained periods. Students who struggle with handwriting can have underlying impairments that require direct instruction [9]. It is estimated that 10 to 30% of students require specialized instruction in handwriting [2,19] due to underlying cognitive, neurological, and physical disruptions. Other measures suggest that the number of students who struggle with handwriting varies more significantly between 5 and 44% [20]. Due to the complex nature of handwriting and its ubiquitous place in schools, strong handwriting skills are an asset and need for students to succeed in their academic environment.

A handwriting curriculum is often spurred by educators with support from specialists and utilized as an intervention for struggling students yet is also implemented as a part of general classroom education. Handwriting difficulty is the number one reason for a referral to school-based occupational therapy [8,21]. Handwriting curriculums focus on correctly forming and aligning letters and words for written communication. Some examples of commercially available handwriting curriculums and programs developed by occupational therapists include Handwriting Without Tears™ [22], Write Start [23,24], and Size Matters Handwriting Program. Other commercial programs, such as D’Nealian and Zaner-Bloser, are also implemented to address handwriting instruction and are widely used in schools. Systems such as Wilson Fundations®, Lindamood Bell®, and Orton-Gillingham© specifically support students with learning disabilities or special education identifications of specific learning disabilities.

Hoy, et al. [25] noted that handwriting practice was most important for improving handwriting outcomes. Hoy et al. reported that handwriting practice was necessary to have significant changes and improve skills [25]. Furthermore, handwriting practice that is specific to the context of the handwriting task has been shown to improve handwriting with the most efficacy [25-27]. There is limited literature regarding the dosage parameters related to handwriting curricula across various settings. Such parameters would inform occupational therapy professionals and educators about the intensity, frequency, and duration of handwriting curricula and the settings where they have been implemented. Therefore, we explore the frequency, intensity, and duration of published peer-reviewed outcome studies on handwriting curriculums used by occupational therapists and/or educators among pediatric populations in school, community, and private/outpatient settings.

We sought to answer the following research questions.

1. What is the frequency, duration, and intensity of groupbased

handwriting intervention programs using commercial

curriculums?

Method

Design

To address the research question, we employed a scoping review design. Scoping reviews are conducted for various purposes, such as identifying the types of existing evidence within a specific field, clarifying key concepts and definitions in the literature, and exploring research methodologies related to a particular topic. They are also valuable for pinpointing essential characteristics or factors associated with a concept, serving as a preliminary step before a systematic review, and identifying gaps in current knowledge. In this study, we focused on examining dosage factors related to handwriting curricula among students, primarily in educational settings [28]. We followed the five-step procedure outlined by Arksey and O’Malley [29], which includes: Stage 1 - Identifying the research question; Stage 2 - Identifying relevant studies; Stage 3 - Study selection; Stage 4 - Charting the data; and Stage 5 - Collating, summarizing, and reporting the results.

Inclusion Criteria

For an article to be included in the review, the potential article needed to meet the study’s inclusion criteria. 1) peer-reviewed journal between 2000 and 2020; 2) intervention aimed to improve student’s handwriting; 3) Used a commercially based curriculum (Big Strokes for Little Folks, Handwriting/Learning Without Tears, Loops Hoops, and other Groups, etc.); 4) sample can include neurotypical and neuro-atypical participants; 5) sample used in the study must include children aged 5-12 years or in the 1st – 6th grade; 6) The intervention can focus on manuscript or cursivestyle penmanship; 7) study methods must describe at least one component of dosage (intensity, duration & frequency); and 8) outcomes must demonstrate a statistical significance at or less than .05.

We operationalized key terms for this study. For this study, handwriting curriculums were defined as teacher or therapistled instruction of key handwriting topics (e.g., upper, and lowercase letter formation) in a structured and sequential order (e.g., alphabetical or developmental) that are disseminated commercially with paper or computer-based consumables for an individual student or entire classroom.

An outcome study was defined as any study that takes a client’s experiences, preferences, and values into account and is intended to provide scientific evidence relating to decisions made by all who participate in health care [30] Intervention frequency was defined as the number of treatment sessions the client takes part in AOTA. Intervention intensity refers to the length of each intervention session reported in minutes [31-35]. Lastly, the intervention duration is the length of the intervention plan reported in weeks or days.

Procedure

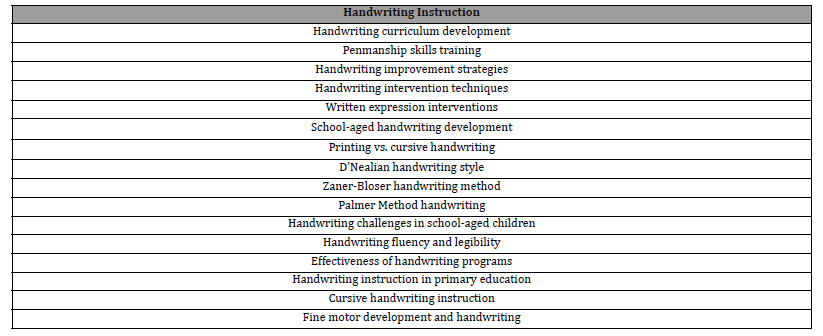

Scholarly databases were assigned to members of the research team consisting of three occupational therapists with research and pediatric practice experience. The databases searched included Google Scholar, OT seeker, American Occupational Therapy Association children and youth special interest section, Medline, EbscoHost, ERIC, and CINAHL. The following terms were used as a part of the search: handwriting, handwriting curriculum, penmanship training, handwriting intervention, written expression (handwritten based), school-aged children, printing versus cursive, D’Nealian, Zaner Bloser, Palmer Method, etc. (Table 1).

Table 1:Search Terms.

Data Analysis

Using a spreadsheet program, the data were analyzed through descriptive statistics (mean and standard deviation) of the three components of dosage (intensity, frequency, and duration) across the 24 outcomes studies. Further, the data were categorized according to the treatment setting (outpatient hospital clinic, traditional and non-traditional school-based, & summer camp).

Results

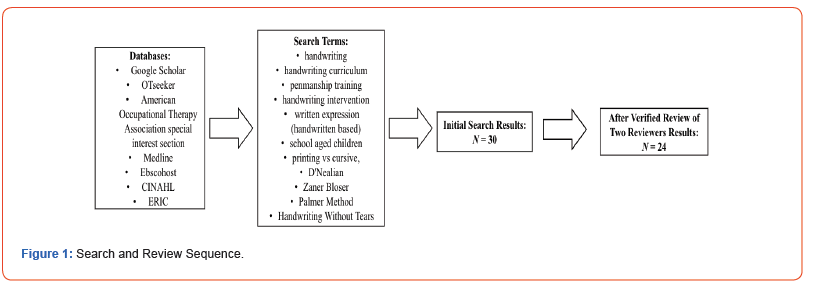

Six articles were excluded as they were 1:1 Occupational therapy intervention sessions and not small group/whole classroom, intervention dosage was not clearly described, focused more on evaluation vs. intervention of handwriting, or were qualitative (Figure 1).

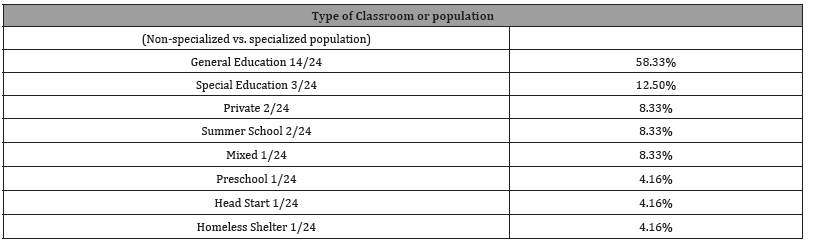

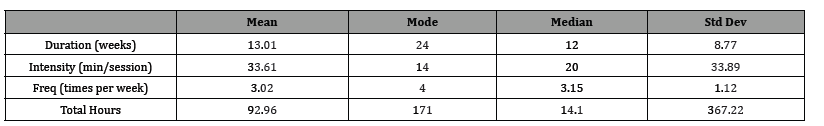

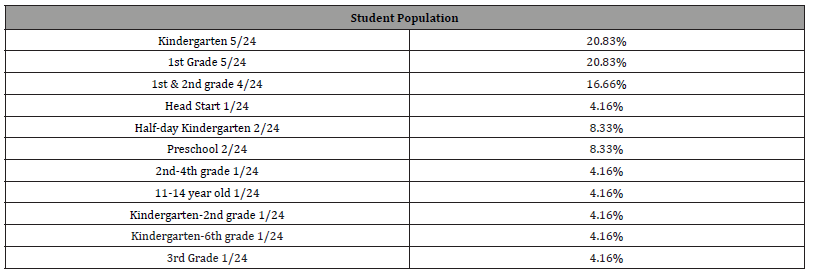

The findings revealed that the studies that used formal handwriting curricula had dosage parameters for the categories of the number of weeks (M=13.01, SD = 8.77), the number of minutes per session (M= 33.61, SD = 33.89), sessions per week (M=3.02, SD = 1.12), and total intervention hours (M=92.96, SD = 367.33) (Table 1). A notable outlier related to the minutes per session (M= 33.61, SD = 33.89) where one study implemented an intensive weeklong summer camp approach. The most common classroom population with implemented handwriting curricula was embedded in general education classrooms (14/24 articles or 58.33%). The handwriting curriculum was implemented within the special education classroom in 3/24 articles or 12.50%. Other classroom populations where handwriting curriculum was implemented include private (8.33% or 2/24 articles), summer school, and mixed classrooms, at 8.33% and 2/24 articles each. Preschool, Head Start, and homeless shelters were also identified in one article, making up 4.16% of the total articles (Table 2 and Table 3).

Table 2:Classroom Type.

Table 3: Dosage Parameters.

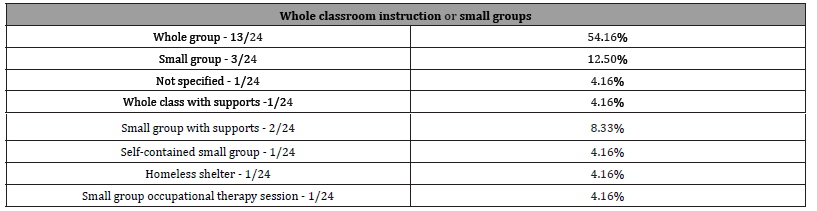

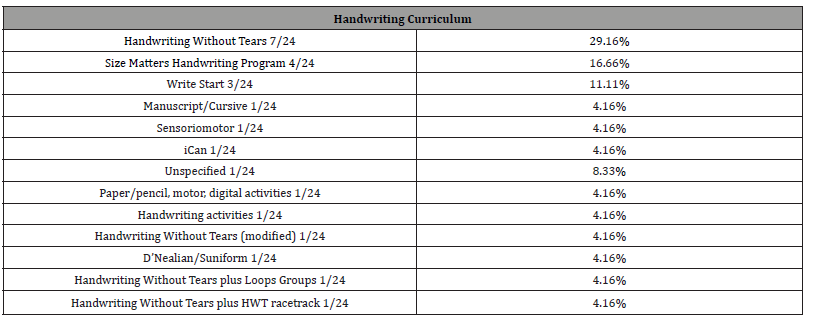

Classroom instruction in whole groups was identified in 13/24, or 54.16% of articles, small groups in 3/24 or 12.50%, and three of the 24 articles described a handwriting curriculum delivered in small groups with support. One of 24 articles identified the following instruction: 1) not specified, 2) the whole group with support, 3) self-contained small groups, 4) homeless shelters, and 5) small group occupational therapy sessions (Table 3). Dosage parameters across curricula were difficult to track as some studies blended aspects of manuscript and cursive of the same curricula (e.g. Handwriting Without Tears), blended manuscript and cursive of differing curricula (e.g. Handwriting Without Tears and Loops, Hoops and Other Groups), blended curricula with other preparatory or foundational skill development (Table 4 and Table 5).

Table 4:Instructional Delivery.

Table 5:Student Population.

Most of the studies reported using the Handwriting Without Tears (40.72%) handwriting curriculum (Table 6). We were unable to distinguish which curriculum or grade level needed more or less time per type of curriculum used. Additionally, effectiveness among the different curricula was not assessed as it was outside the scope of the study.

Table 6:Curriculum Used.

Discussion

This study aimed to explore the frequency, intensity, and duration of published peer-reviewed outcome studies focused on handwriting curriculums used among pediatric populations. The findings of this study are the first of its kind to explore the concept of dosage from the perspective of the implementation of handwriting curricula in the peer-reviewed literature. This study provides professionals who implement handwriting training with detailed information about the intensity, duration, and frequency of formal/ commercially available handwriting curricula, the settings in which they are used, and the populations with which they are used. Such information may aid educational knowledge users (educators; special and regular education), occupational therapists, principles, superintendents, etc., in determining the most appropriate dosages with which to use a handwriting curriculum based on student population, classroom/setting, and type of delivery (individual, small group, and whole classroom).

Though this study yielded meaningful findings, there are several limitations with the design and analysis of the study. First, the search parameters and databases may not have captured all the possible articles that explored the effectiveness of a given handwriting curriculum. Most articles found were from occupational therapyrelated journals, which may not accurately represent studies published within education-focused journals, though we did use education-based databases (ERIC and EBSCOhost). The analysis of dosage parameters within the handwriting curriculum included only research studies that reported significance. However, the differences in the types of analysis (e.g., parametric versus nonparametric) and the types of outcomes (e.g., handwriting legibility versus writing speed) make generalizations to whole classroom or small group intervention among typical or neurotypical populations difficult. Organizing the dosage parameters based on the type of analysis and outcomes would have improved the study. Additionally, the analysis of this study did not focus specifically on the dosage of handwriting curriculums specific to the type of handwriting style, e.g., manuscript versus cursive. Finally, the studies were conducted internationally (Canada, Great Britain, Europe, United States of America, etc.). Therefore, implementation of the curriculum may have some slight variance due to the culture of each intervention setting and varying educational standards and may have lacked fidelity to the expectations for implementation (within each curriculum’s directions).

This study aimed to characterize the dosage of handwriting curriculums from the available peer-reviewed articles. Consequently, the findings reaped more questions than answers. Further research related to the level of dosage, the handwriting curriculum, and the clinical and statistical significance level would contribute to the literature. Evaluating the handwriting curriculum dosage parameters based on the type of analysis and outcomes would further the dialog regarding which curriculum might work best with the kind of client, student, or the whole classroom. Further research is warranted to explore why education and health care professionals use specific handwriting curriculums over others (e.g., Handwriting Without Tears vs. Size Matters).

Conclusion

The study highlights that handwriting practice is crucial for improving handwriting outcomes among students, particularly in general education settings. Occupational therapists should advocate for the implementation of structured handwriting curricula, such as Handwriting Without Tears, to enhance fine motor skills and academic performance among students. The findings indicate specific dosage parameters (frequency, duration, & intensity) for handwriting interventions, with an average of 3.02 sessions per week over approximately 13 weeks. Occupational therapists should consider these dosage parameters when designing intervention plans to ensure effective instruction and practice in handwriting for both neurotypical and neuro-atypical populations.

References

- Ziviani J, Wallen M (2006) The development of graphomotor skills. Hand Function in the Child: Foundations for Remediation, 2nd Ed, Henderson A, Pehoski C Mosby (Eds.).

- Feder KP, Majnemer A (2007) Handwriting development, competency, and intervention. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology 49(4): 312-317.

- Santangelo T, Graham, S (2016) A Comprehensive Meta-Analysis of Handwriting Instruction. Educational Psychology Review 28: 225-265.

- Mangen A, Velay JL (2010) Digitizing literacy: Reflections on the haptics of writing. Advances in haptics 1(3): 86-401.

- Marr D, Cermak S, Cohn ES, Henderson A (2003) Fine Motor Activities in Head Start and Kindergarten Classrooms. American Journal of Occupational Therapy 57(5): 550-557.

- Mchale K, Cermak S (1992) Fine motor activities in elementary school: Preliminary findings and provisional implications for children with fine motor problems. American Journal of Occupational Therapy 46(10): 898-903.

- McMaster E, Roberts T (2016) Handwriting in 2015: A main occupation for primary school-aged children in the classroom? Journal of Occupational Therapy, Schools & Early Interventions 9(1): 38-50.

- American Occupational Therapy Association (2014a). Guidelines for supervision, roles, and responsibilities during the delivery of occupational therapy services. American Journal of Occupational Therapy 68: S16-22.

- Weintraub N (2019) Best Practices in Literacy: Handwriting and Written Expression to Enhance Participation. GF Clark, J E. Rioux, BE Chandler (Eds.), Best Practices for Occupational Therapy in Schools pp. 413-420.

- Cameron CE, Brock LL, Murrah WM, Bell LH, Worzalla SL, et al. (2012) Fine motor skills and executive function both contribute to kindergarten achievement. Child development 83(4): 1229-1244.

- Suggate S, Pufke E, Stoeger H (2019) Children’s fine motor skills in kindergarten predict reading in grade 1. Early childhood research quarterly 47: 248-258.

- Schneck CM, O'Brien SP (2020) Assessment and Treatment of Educational Performance. In J. C. O'Brien & H. Kuhaneck (Eds.), Case-Smith's Occupational Therapy for Children and Adolescents, Elsevier Vol 8.

- Graham S, Struck M, Santoro J, Beringer VW (2006) Dimensions of good and poor handwriting legibility in first and second graders: Motor programs, visual-spatial arrangement, and letter formation parameter setting. Developmental Neuropsychology 29(1): 43-60.

- Greifeneder R, Zelt S, Seele T, Bottenberg K, Alt A (2012) Towards a better understanding of the legibility bias in performance assessments: The case of gender-based inferences. British Journal of Educational Psychology 82(3): 361-374.

- Engel-Yeger B, Naguaker-Yanuv L, Rosenblum S (2009) Handwriting performance, self-reports, and perceived self-efficacy among children with dysgraphia. American Journal of Occupational Therapy 63(2): 182-189.

- Dinehart L (2015) Handwriting in early childhood education: Current research and future implications. Journal of Early Childhood Literacy 15(1): 97-118.

- Fancher LA, Priestley-Hopkins DA, Jeffries LM (2018) Handwriting Acquisition and Intervention: A Systematic Review. Journal of Occupational Therapy, Schools, & Early Intervention 11(4): 454-473.

- Connelly V, Gee D, Walsh E (2007) A comparison of keyboarded and handwritten compositions and the relationship with transcription speed. British Journal of Educational Psychology 77(2): 479-492.

- Karlsdottir R, Stefansson T (2002) Problems in developing functional handwriting. Perceptual Motor Skills 94(2): 623-662.

- Feng L, Lindner A, Ji XR, Joshi RM (2017) The roles of handwriting and keyboarding in writing: A meta-analytic review. Reading and Writing 1-31.

- Barnes KJ, Beck AJ, Vogel KA, Grice KO, Murphy D (2003) Perceptions regarding school-based occupational therapy for children with emotional disturbances. American Journal of Occupational Therapy 57(3): 337-341.

- Olson J, Knapton E (2008) Handwriting Without Tears (3rd ed). Western Psychological Services.

- Case-Smith J, Holland T, Bishop B (2011) Effectiveness of an integrated handwriting program for first-grade students: A pilot study. American Journal of Occupational Therapy 65(6): 670-678.

- Case-Smith J, Holland T, Lane A, White S (2012) Effect of a coteaching handwriting program for first graders: One-group pretest-posttest design. American Journal of Occupational Therapy 66(4): 396-405.

- Hoy MMP, Egan MY, Feder KP (2011) A systematic review of interventions to improve handwriting. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy 78(1): 13-25.

- Case-Smith J, Weaver L, Holland T (2014) Effects of a classroom-embedded occupational therapist-teacher handwriting program for first-grade students. American Journal of Occupational Therapy 68(6): 690-698.

- Howe T, Roston K, Sheu C, Hinojosa J (2013) Assessing handwriting intervention effectiveness in elementary school students: A two-group controlled study. American Journal of Occupational Therapy 67(1): 19-26.

- Munn Z, Peters MD, Stern C, Tufanaru C, McArthur A, et al. (2018) Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Medical Research Methodology 18(1): 143.

- Arksey H, O'Malley L (2005) Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology 8(1): 19-32.

- Gee B, Gerber D, Butikofer R, Covington N, Lloyd K (2018) Frequency, Intensity, and Duration of CIMT: A Content Analysis. Neuro Rehablitation 42(2):167-172.

- Gee B, Lloyd K, Devine N, Erin Tyrrell, Trisha Evans, et al. (2016) Dosage parameters in pediatric outcome studies reported in 9 peer-reviewed occupational therapy journals from 2008 to 2014: a content analysis. Rehabilitation Research and Practice 2016: 14.

- Geyh S, Peter C, Müller R, Bickenbach JE, Kostanjsek N, et al. (2011) The personal factors of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health in the literature–a systematic review and content analysis. Disability and rehabilitation 33(13-14): 1089-1102.

- Levac D, Colquhoun H, O’Brien KK (2010) Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implementation Science 5(1): 69.

- Swinth Y, Tomlin G, Luthman M (2015) Content anal- ysis of qualitative research on children and youth with autism, 1993–2011: Considerations for occupational ther-apy services. American Journal of Occupational Therapy 69(5): 6905185030p 1-9.

- Statistics, N. C. f. E. ((n.d).). Literacy Domain.

-

Bryan Gee*, Kimberly Lloyd and Jane Ewoniuk. Exploring the Dosage of Handwriting Curricula Among School-Aged Children. Acad J Health Sci & Res. 1(4): 2025. AJHSR.MS.ID.000518.

Handwriting; Penmanship, School age; Curriculum

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.