Research Article

Research Article

The Role of Social Determinants of Health in Missed Colorectal Cancer Prevention Among Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease from a Safety-Net Hospital

Antonio Pizuorno Machado¹, Cinthana Kandasamy¹, Po-Hong Liu¹, Ishak Mansi2,3 and Moheb Boktor1*

1Division of Digestive and Liver Diseases, UT Southwestern, Dallas, TX 75390, USA

2Department of Internal Medicine, University of Central Florida College of Medicine, Orlando, FL 38217, USA

3Education Service, Orlando VA Healthcare System, Orlando, FL 38217, USA

Moheb Boktor, Division of Digestive and Liver Diseases, UT Southwestern, Dallas, TX 75390, USA

Received Date:December 2, 2025; Published Date:January 09, 2026

Abstract

Aim: Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) increases the risk of colorectal cancer (CRC). This study aimed to assess the social determinants of

health (SDH) and the burden of CRC among IBD patients within a large urban safety-net health system and to identify potential missed opportunities

for CRC prevention.

Methods: We performed a retrospective review of electronic medical records for patients aged 18 and older treated at an urban safety-net

health system from January 2010 to February 2024. Patients were included if they: 1) had diagnoses of both IBD and CRC, identified using ICD codes;

and 2) had undergone at least one colonoscopy during the study period. We evaluated SDH, healthcare utilization, IBD and CRC characteristics.

Results: Fifteen patients met the inclusion criteria (9 with ulcerative colitis). Demographic characteristics included: 66.7% male and 60%

white. Seven patients (46.7%) received healthcare services through county-hospital financial assistance. Majority of patients had transportation

barriers (67%). Sixty percent had not seen a primary care provider or gastroenterologist within the past year before CRC diagnosis. Financial

barriers (38.5%) were a documented cause of therapy interruption or delayed follow-up. There were 9 (60%) deceased patients; overall survival

ranged from 1 to 137 months (median: 9 months).

Conclusion: Transportation barriers, unemployment and low household median income were the predominant SDH among IBD patients who

developed CRC. Gastroenterology follow-up, use of advanced therapeutics, and timely disease activity monitoring were infrequent in this cohort.

Financial barriers and resource limitations contributed substantially to the care burden for low-income patients.

Keywords:Inflammatory Bowel disease; Colorectal cancer; Social determinants of health

Abbreviations and Acronyms:IBD: Inflammatory bowel disease; CC: Colorectal cancer; SDH; Social determinants of health; CD: Crohn’s disease; UC: Ulcerative colitis; PSC: Primary sclerosing cholangitis; CAC: Inflammatory bowel disease associated colon cancer; sCRC: Sporadic colorectal cancer

Introduction

Inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD), including Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC), are chronic, progressive inflammatory disorders of the gastrointestinal tract resulting from dysregulated immune response to intestinal microbiota in genetically predisposed individuals [1,2]. The global incidence and prevalence of IBD continue to rise, particularly in North America, with UC affecting 37.5–248.6 per 100,000 person-years and CD 0–20.2 per 100,000 person-years [3-5]. Recent data indicate a growing burden of IBD among racial and ethnic minority populations, reflecting changes in disease epidemiology and revealing ongoing inequities in healthcare access and outcomes [6–9]. Projections estimate that more than five million individuals worldwide will be affected by IBD by 2050, underscoring the expanding public health impact of these conditions [10].

A well-established complication of IBD, particularly longstanding UC and Crohn’s colitis, is an elevated risk of colorectal cancer (CRC). Studies demonstrate that these patients experience a two to threefold increased risk of CRC compared with the general population, though estimates vary based on disease duration, extent, severity of inflammation, and study period [3,4]. IBD-associated colorectal cancer (CAC) serves as a model of inflammation-driven carcinogenesis, where chronic inflammation induces oxidative stress, promoting genetic and epigenetic alterations that activate oncogenes and inactivate tumor suppressor genes [3]. The molecular mechanisms of CAC overlap with those of sporadic colorectal cancer (sCRC), involving chromosomal instability, microsatellite instability, and the CpG island methylator phenotype [3].

Despite substantial advances in IBD management, the development of biologic and small-molecule therapies, improved surveillance strategies, and updated clinical guidelines important gaps persist in translating these advances into equitable preventive care, in particular social determinants of health. Social determinants of health (SDH) are the non-medical factors including socioeconomic status, education, housing, neighborhood environment, access to healthcare, and social support. These structural and contextual factors influence disease outcomes, and access to timely, high-quality care.

Social inequities profoundly affect patients with IBD. Non- White patients experience higher hospitalization rates, longer stays, increased costs, higher readmission rates, and more postoperative complications compared to White patients [7]. Financial hardship, limited health literacy, and inadequate or unstable insurance coverage further exacerbate disparities in disease management. A 2020 study found that one in eight patients with IBD faced at least one major socioeconomic hardship, including food insecurity, limited social support, or cost-related medication nonadherence [8]. Furthermore, patients insured through Medicaid face challenges such as inconsistent access, underinsurance, and high out-ofpocket costs, which hinder engagement with preventive care and continuity of treatment [7,8]. Parallel disparities exist in colorectal cancer prevention and outcomes. Racial and ethnic minority populations and individuals with lower socioeconomic status are disproportionately affected by CRC and more likely to face barriers to screening, follow-up of abnormal results, and access to curative interventions [5]. These inequities stem from a complex interplay of individual, provider, system-level, and policy factors, manifesting as later-stage diagnoses and worse survival among Black and Hispanic/Latino patients compared to their White counterparts [5- 7]. Patients without insurance or with Medicaid coverage are more likely to present with metastatic disease and receive suboptimal treatment, underscoring the critical role of insurance status as a determinant of cancer outcomes [5].

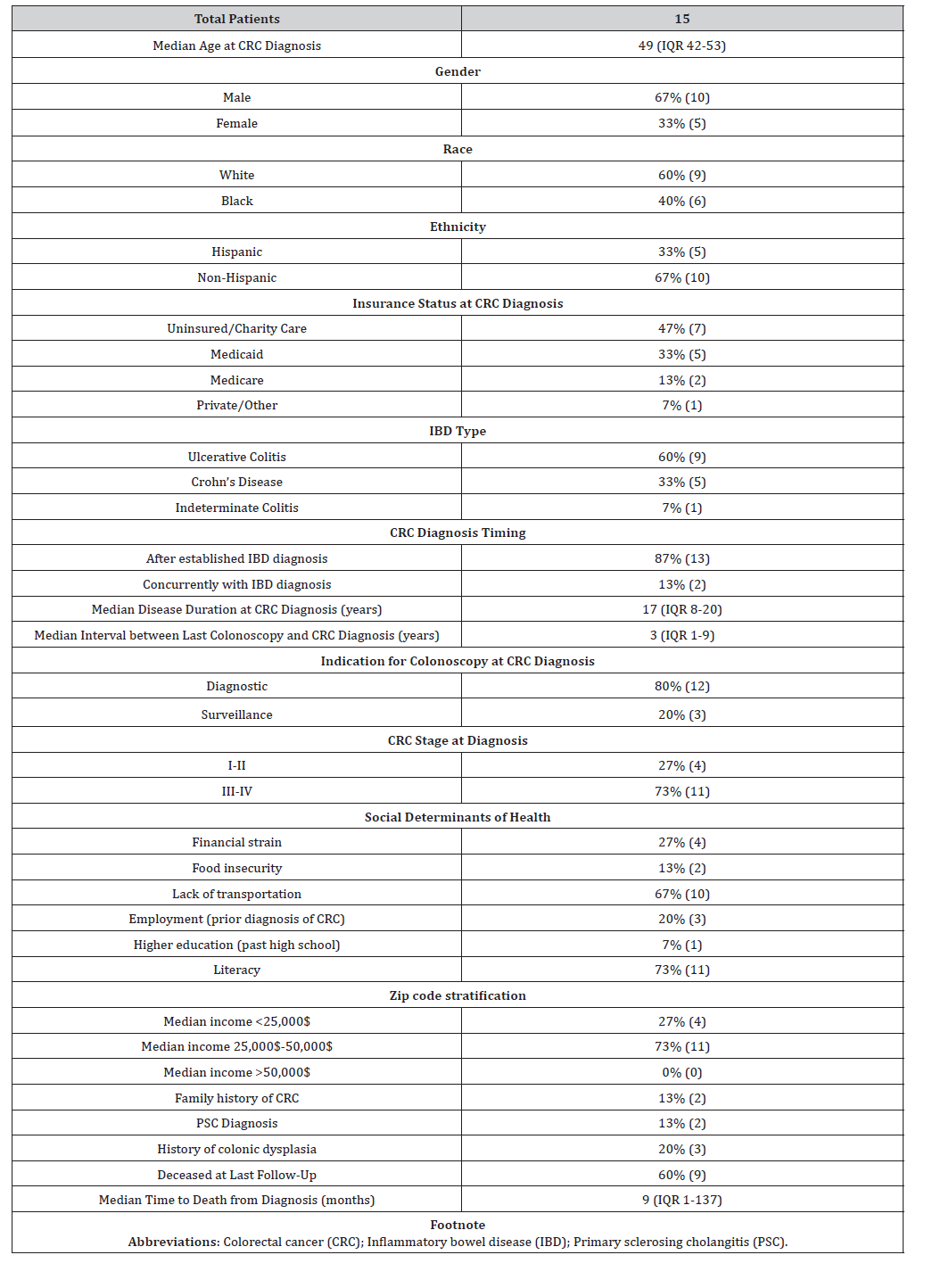

Safety-net health systems which provide care to disproportionately low-income, uninsured, and underinsured populations occupy a critical yet underexamined position at the intersection of IBD, CRC risk, and social vulnerability. They often care for patients disproportionately affected by the social and structural inequities underlying both IBD and CRC. Yet, the intersection of SDH, IBD care, and missed opportunities for CRC prevention in safetynet systems remains underexplored. This study aims to assess the burden of colorectal cancer among patients with inflammatory bowel disease in a large urban safety-net health system and to identify social and structural determinants associated with missed opportunities for colorectal cancer prevention. By examining these interrelated factors, we seek to highlight actionable gaps in care and inform interventions to promote equity in cancer prevention for vulnerable patient populations (Table 1).

Table 1:Patient baseline characteristics along with social determinants of health.

Materials and Methods

We conducted a retrospective case series using electronic medical record from a prospectively collected cohort of patients with inflammatory bowel disease with diagnosis of colorectal cancer at an urban safety net center. All included patients were diagnosed with inflammatory bowel disease (either CD, UC or indeterminate colitis), along with colorectal cancer either before or after the diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease. ICD codes were used to identify the patients. Inclusion criteria were: 1) over 18 years old, 2) treated between January 2010 to February 2024 and 3) patients had undergone at least one colonoscopy during the study period. The diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease was done either in the center or outside, same scenario for colorectal cancer.

Information about SDH were obtained from notes embedded in our electronic health records, information collected included demographics (race and ethnicities), use of financial assistance program, transportation barriers, median income of resided area through zip code (our study used median income classification from the most recent US census), food insecurity, education level, and employment status; this information was either filled by the patient or collected by ancillary staff. As for clinical aspects, we collected data in regards of the stage of cancer at diagnosis, family history, history of primary sclerosis cholangitis, history of dysplasia.

Results

Baseline characteristics

The median age at colorectal cancer diagnosis was 49 years old (IQR 42-53). Most patients were males (67% with 10 patients) comparing to females (33% with 5 patients). 9 patients (60%) identified as White, and 6 patients (40%) as African Americans being. In regards of ethnicity, 5 patients identified as Hispanic (33%). Regarding IBD subtype, UC was the most common diagnosis (n = 9, 60%), followed by CD (n = 5, 33%); one patient (7%) had indeterminate colitis.

Cancer characteristics

The majority of patients were diagnosed with CRC after established IBD diagnosis in 13 patients (87%), CRC was diagnosed at the same time as IBD in 2 patients (13%). At the time of CRC, the median duration of IBD was 17 years (IQR 8-20). The medicine interval between last colonoscopy and CRC was 3 years (IQR 1-9). The indication for colonoscopy when cancer was diagnosed was predominately diagnostic in 12 patients (80%) with only 3 patients (20%) for surveillance/screening purposes. At the time of diagnosis, majority of patients were diagnosed with stage III/IV in 11 patients (73%) versus stage I-II in 4 patients (27%).

In regards as other cancer characteristics, only 2 patients (13%) had family history of CRC. Three patients (20%) had a prior diagnosis of colonic dysplasia. The median time from CRC diagnosis to death was 9 months (IQR 1-137).

Social determinants of health

Most of the patients included in the cohort lacked medical insurance in at least 7 patients (47%), followed by patients with Medicaid in 5 patents (33%). Transportation barriers were the most frequently reported social challenge, affecting 10 patients (67%) and limiting access to clinic visits and procedures. Financial strain was reported in five patients (27%). Additionally, 11 patients (73%) demonstrated limited health literacy, including difficulty navigating the healthcare system.

Most patients resided in areas with a median income of 25,000- 50,000$ in 11 patients (73%), a significant amount of our patients in 27% (4 patients) had a medical income of less than 25,000$.

Author Contributions

J Velji-Ibrahim wrote and revised the manuscript. K Devani revised the manuscript and is the article guarantor.

Discussion

In this case series from a large urban safety-net hospital, we identified a substantial burden of adverse SDH amongpatients with IBD who developed CRC Nearly half of the patients were uninsured (47%), and additional one-third were insured under Medicaid (33%). Transportation was a major barrier, with 67% of patients reporting difficulties attending clinic appointments, and 73% reported challenges navigating the healthcare system. Two-thirds of patients were White (60%) and non-Hispanic (67%). These findings highlight the intersection of chronic inflammatory disease, cancer risk, and structural vulnerability within safety-net settings and underscore the potential role of SDH in missed opportunities for CRC prevention and early detection.

Consistent with prior literatures, patients with CAC often experience worse survival than sCRC patients. Tumors are more frequently located in the right colon, and the disease appears more frequently in males and at a younger age compared with sporadic CRC cases [9,11]. In a Mayo Clinic study of patients diagnosed between 1996 and 2011, the mean age at CRC diagnosis in IBD patients was 67 years [12]. Analysis of the National Inpatient Sample (NIS) database, which included over 57,000 patients, showed a lower prevalence of CRC in females compared with males, and Black race appeared to confer a protective effect [13]. Another NIS-based study reported that the majority of CAC patients (55.9%) had private insurance (p=0.03), suggesting that patients lacking stable insurance coverage may be underrepresented in existing datasets [13].

Although data specifically examining SDH in IBD is limited, national surveys provide insight into key social risks. A United States of America. survey of 572 patients with IBD found that 22% reported food insecurity, 9% experienced transportation barriers, and 41% experienced discrimination. Social risks were more prevalent among racial and ethnic minorities, with 37% of Black patients and 28% of Hispanic patients reporting such challenges, compared with 12% of non-Hispanic White patients [14]. Similarly, a study conducted by the Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation of New York found that 39% of patients were uninsured and a comparable proportion reported an annual household income below $50,000. In this study, Hispanic and Black patients experienced worse outcomes and greater disability [15].

Evidence from other chronic diseases suggests that addressing SDH can improve outcomes. A large systematic review of United States of America cancer screening interventions reported that programs targeting SDH increased screening rates by a median of 8.4 percentage points across breast, cervical, and colorectal cancer. Interventions focused on improving healthcare access and quality, enhancing demand for screening (90% of studies), and reducing barriers to services (84%) [16]. These findings suggest that similar strategies may benefit CAC patients. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has implemented funded programs to address disparities in IBD, including initiatives from 2018 to 2024 to evaluate outcomes and identify improvement strategies [17], and subsequent programs from 2023 to 2028 aimed at developing digital health tools and educational engagement tailored to underserved populations [18]. Targeted interventions addressing transportation and access to care may similarly improve outcomes in this vulnerable population, though prospective studies are needed to confirm this.

Conclusion

This study provides a unique perspective by focusing on IBD patients treated in a safety-net hospital, representing one of the most vulnerable populations affected by CRC. The study has several limitations, including the small sample size, retrospective design, and the subjective nature of patient-reported questionnaires, which may affect the generalizability and reliability of the findings.

Patients with IBD who develop CRC within safety-net health systems face substantial social and structural barriers that may contribute to delayed diagnosis and advanced disease at presentation. Integrating SDH-informed interventions into IBD care and CRC surveillance strategies may represent an important opportunity to improve equity and outcomes for this high-risk population.

References

- Eaden JA, Abrams KR, Mayberry JF (2001) The risk of colorectal cancer in ulcerative colitis: a meta-analysis of population-based cohort studies. Gastroenterology 120(4): 1104-1112.

- Ungaro R, Meandrous S, Allen PB, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Colombel JF (2017) Ulcerative colitis. Lancet 389(10080): 1756-1766.

- Khan N, Patel D, Trivedi C (2023) Molecular pathogenesis of colitis-associated colorectal cancer: immunity, genetics, and intestinal microecology. Inflamm Bowel Dis 29(10): 1648-1663.

- Smith A, Jones B, et al. (2000) Microsatellite instability in IBD-associated neoplastic lesions is associated with hypermethylation and diminished expression of the DNA mismatch repair gene hMLH1. Gut 47(3): 425-432.

- (2021) Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Colorectal cancer risk factors and screening among the uninsured of Tampa Bay: a free clinic study. Prev Chronic Dis 18: E16.

- Castañeda-Avila MA, Tisminetzky M, Oyinbo AG, Lapane K (2024) Racial and ethnic disparities in use of colorectal cancer screening among adults with chronic medical conditions: BRFSS 2012–2020. Prev Chronic Dis 21: 230257.

- Anyane-Yeboa A, Quezada S, Rubin DT, Balzora S (2022) The impact of the social determinants of health on disparities in inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 20(11): 2427-2434.

- Nguyen NH, Khera R, Dulai PS, Boland BS, Ohno-Machado L, et al. (2020) National estimates of financial hardship from medical bills and cost-related medication nonadherence in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases in the United States. Inflamm Bowel Dis 27(7): 1068-1078.

- Khan M, et al. (2022) Survival outcomes and clinicopathologic features of inflammatory bowel disease–associated colorectal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Dis Colon Rectum 65(5): e147-159.

- Yang, K., Zhang, C., Gong, R. et al. (2025) From west to east: dissecting the global shift in inflammatory bowel disease burden and projecting future scenarios. BMC Public Health 25: 2696.

- Jess T, et al. (2012) Risk of colorectal cancer in inflammatory bowel disease: a meta-analysis of population-based cohort studies. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 10(6): 639-645.

- Beaugerie L, et al. (2013) Colorectal cancer in inflammatory bowel diseases: a population-based study. Gastroenterology 145(1): 166-175.e3.

- Kumar A, et al. (2019) Racial disparities in the incidence of colon cancer in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Dig Dis Sci 64(9): 2548-2555.

- Khan N, et al. (2024) Social determinants of health and their association with healthcare utilization and medication adherence in inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 22(5): 1021-30.e2.

- Long MD, et al. (2019) Disparities in disability among patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 25(4): 735-742.

- Akinyemiju T, et al. (2023) Interventions addressing social determinants of health to improve cancer screening uptake: a systematic review. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 32(8): 1023-1034.

- (2018) Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Etiology and outcome of inflammatory bowel disease program (2018–2024) [Internet]. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

- (2023) Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Improving health outcomes for patients with inflammatory bowel disease (2023–2028) [Internet]. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

-

Antonio Pizuorno Machado, Cinthana Kandasamy, Po-Hong Liu, Ishak Mansi and Moheb Boktor*. The Role of Social Determinants of Health in Missed Colorectal Cancer Prevention Among Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease from a Safety-Net Hospital. Acad J Gastroenterol & Hepatol. 4(4): 2026. AJGH.MS.ID.000591.

-

Inflammatory Bowel disease; Colorectal cancer; Social determinants of health

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

Track Your Article

Refer a Friend

Advertise With Us

Feedback

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.irispublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.irispublishers.com.

Best viewed in