Case Report

Case Report

Diffuse MOC-31 Expression in Hepatocellular Carcinoma: A Diagnostic Challenge

Juhi D Mahadik*, Melton H Fish and Shilpa Jain

Department of Pathology, Baylor College of Medicine, USA

Juhi D Mahadik, Department of Pathology, Baylor College of Medicine, USA.

Received Date: January 24, 2020; Published Date: February 06, 2020

Abstract

Introduction: Distinguishing hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) from other primary liver tumors and metastatic carcinomas involving the liver can be problematic, especially in cases which do not exhibit classic hepatocellular morphology or immunohistochemistry (IHC). The clinical history including chronic viral infections, metabolic syndrome, alcohol, cirrhosis, and alpha-fetoprotein levels (AFP) can often help in this distinction. However, hepatoid adenocarcinoma (HAC), a rare but distinct entity, enters the list of differentials as it closely mimics HCC and may not be distinguished based on histology or immunohistochemistry. HAC is known to be aggressive and has limited therapeutic options; hence its distinction from HCC is crucial.

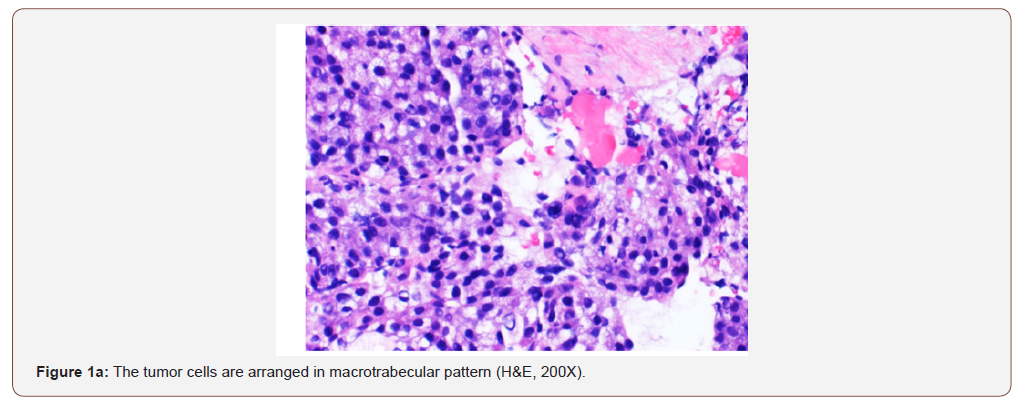

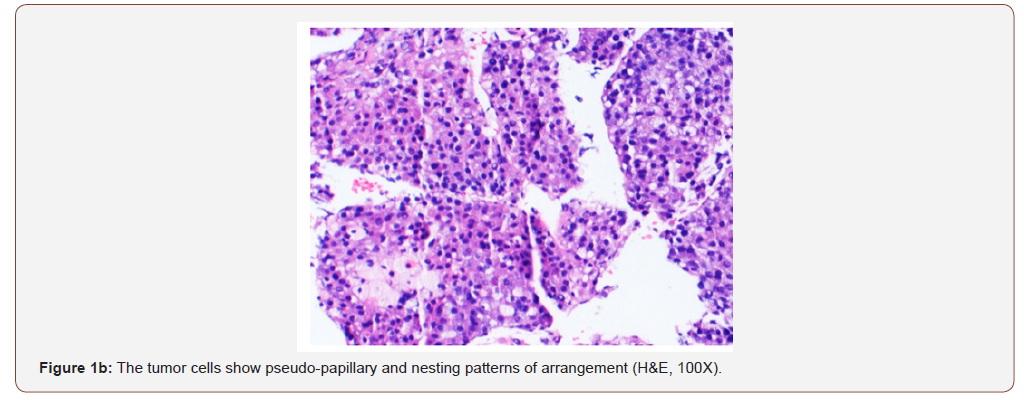

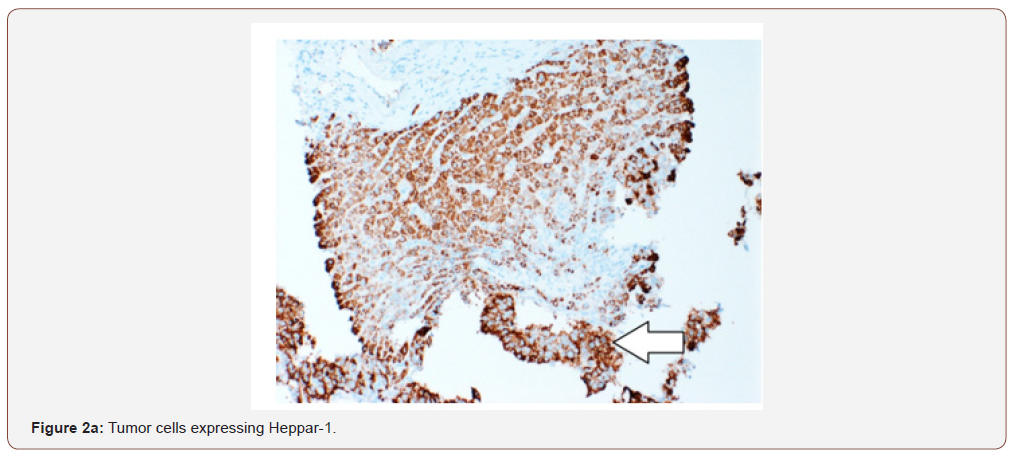

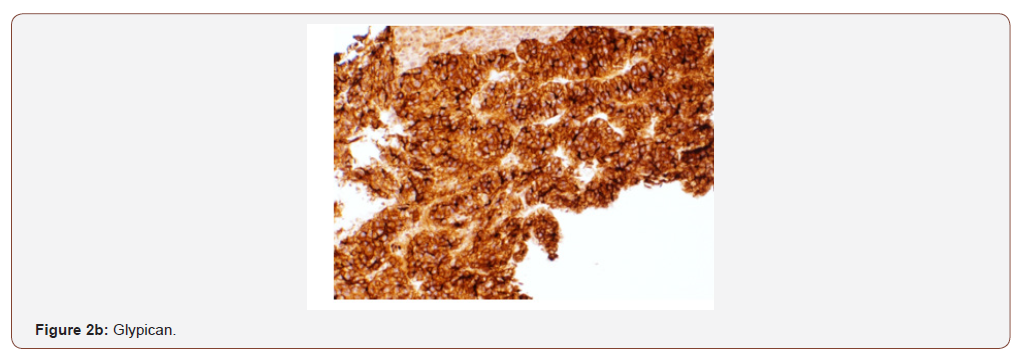

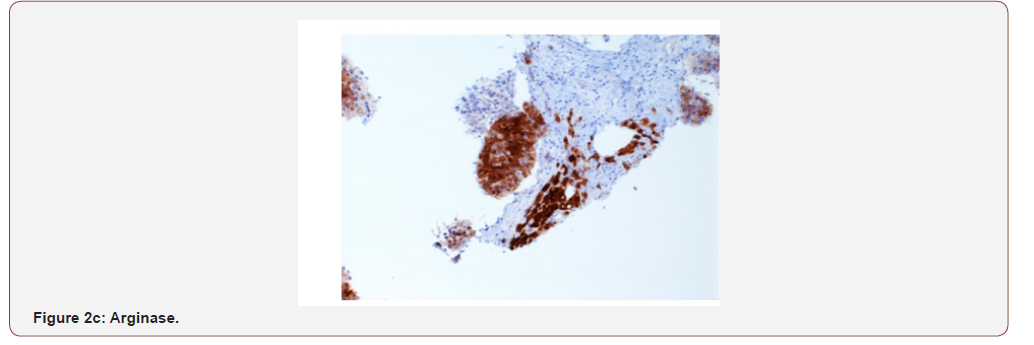

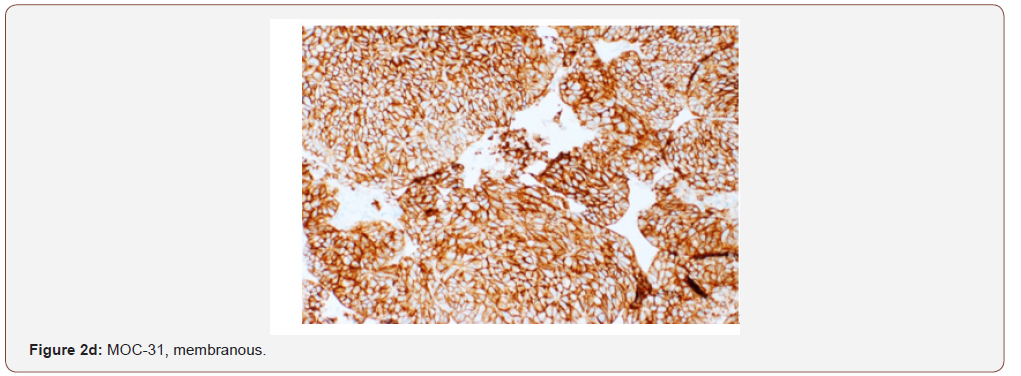

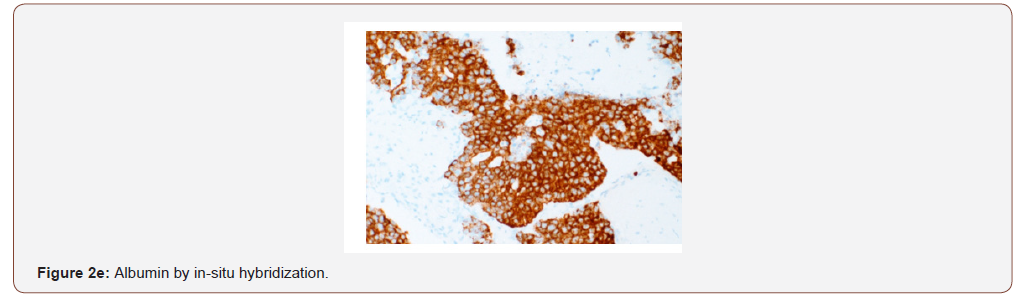

Case presentation: A 54 year old female with a remote history of ovarian cancer presented with multiple liver masses (largest 8 cm) with Hepatitis C infection (RNA quantitative 3700000 IU/ml), and alpha-fetoprotein >2000ng/ml. The chest, abdomen, and pelvis imaging were negative for cirrhosis, masses or lymphadenopathy at other sites. Histologically, the biopsy from liver mass showed tumor cells arranged in macrotrabecular pattern and nests with focal pseudopapillary architecture with macrophages. An immunohistochemical panel showed diffuse strong positivity for glypican, MOC-31 (membranous), Hep-par 1, pancytokeratin and patchy positivity for arginase in tumor cells. CK7, CK20, ER, PR, PAX-8, TTF-1, and p63 were negative. Albumin in-situ hybridization (ISH) was diffusely positive in tumor cells.

Discussion: The morphology and immunohistochemical staining with glypican, Hep-par 1, arginase and albumin ISH favored hepatocellular carcinoma, but the strong expression of MOC-31 which is used to differentiate HCC from cholangiocarcinomas, and metastatic adenocarcinomas added to the diagnostic confusion. MOC-31 is found to be positive in only a subset of HCC cases reported in the literature. The absence of CK7, CK20, ER, PR, TTF-1, p63 and PAX-8 essentially excluded primaries from elsewhere. Nevertheless, the possibility of metastasis from hepatoid adenocarcinoma of other sites was stated and a clinical correlation was recommended.

Keywords: MOC-31; Hepatocellular carcinoma; Hepatoid adenocarcinoma

Abbreviations: HCC: Hepatocellular Carcinoma; ICC: Immunohistochemistry; HAC: Hepatoid Adenocarcinoma; ISH: In-Situ Hybridization; AFP: Alpha-Fetoprotein

Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the most common malignant primary tumor of the liver. HCC affects about a million people every year worldwide. On the other hand, metastatic tumors are widespread in the liver, with metastatic adenocarcinoma constituting the greatest part [1]. Distinguishing HCC from other primary liver tumors and metastatic tumors involving the liver can be problematic, in cases which do not exhibit classic hepatocellular morphology or immunohistochemistry (IHC) and especially if the biopsy material is limited. In such cases, an appropriate panel of immunohistochemical stains, including multiple antibodies with different sensitivities and specificities should be used to make the correct diagnosis. The clinical history including chronic viral infections, metabolic syndrome, alcohol, cirrhosis, and alphafetoprotein levels (AFP) can often help in this distinction. However, hepatoid adenocarcinoma (HAC), a rare but distinct entity, enters the list of differentials as it closely mimics HCC and may not be distinguished based on histology or immunohistochemistry. HAC is known to be aggressive with a disappointing response to chemotherapy [2]; hence its distinction from HCC is crucial.

Case Presentation

infection (RNA quantitative 3700000 IU/ml), and alpha-fetoprotein >2000 ng/ml. Her chest and abdomino-pelvic imaging studies were negative for cirrhosis, masses or lymphadenopathy at other sites. She underwent a percutaneous biopsy from her liver masses. The biopsy showed tumor cells arranged in macrotrabecular pattern, nests and focal pseudopapillary architecture along with macrophages in the stroma, on hematoxylin and eosin staining (Figures 1a & 1b).

An immunohistochemical panel showed diffuse strong positivity for glypican, MOC-31 (membranous), Hep-par 1, pancytokeratin and patchy positivity for arginase and CK19 in tumor cells (Figures 2a- 2d). Polyclonal CEA showed a diffuse canalicular pattern of staining. CK7, CK20, ER, PR, PAX-8, TTF-1, and p63 were negative. The strong expression of MOC-31 in the tumor cells was a very unusual finding; hence an Albumin in-situ hybridization (ISH) was also done which showed showed diffuse positivity in tumor cells (Figure 2e). Owing to the high AFP levels, Hepatitis C infection (in absence of cirrhosis), no evidence of primary tumor elsewhere on imaging along with the morphologic, immunohistochemical and positive Albumin ISH findings, a diagnosis of Hepatocellular carcinoma was made. But the possibility of a hepatoid adenocarcinoma metastasis to the liver from an unknown primary was also stated and a clinical correlation was recommended.

Discussion

Several studies have attempted to distinguish HCC from

metastatic tumors based on immunohistochemistry. A variety of

markers have been used including Hep-par1, pCEA, mCEA, villin,

CD34, CD10, MOC-31, CK7, CK19, CK20, AFP, Ber-EP4, FXIII-A and

TTF-1 [1,3-6]. A review article by Kakar et, al. [7] discusses the

utility of Hep-par1 and MOC-31 in this regard and classifies various

cases into 4 groups. The group of cases with both Hep-par1 and

MOC-31 positivity may include metastatic adenocarcinomas from

stomach, esophagus and lung which express MOC-31 as expected for

adenocarcinomas but also express Hep-par1 which is uncommon.

This group also includes rare cases of HCC with MOC-31 expression.

Various studies have reported MOC-31 expression in HCCs ranging

from 0-19% [1,3-6]. Proca et, al. [8] reported no MOC-31 staining in

HCCs. This finding was confirmed by Porcell et, al. [5] In contrast to

these results, Morrison et al. [4] noted MOC-31 expression in 1of 25

(4%) HCCs and Lau et, al. [3] in 5 of 42 (12%) cases. Karabork et, al.

[1] reported MOC-31 in 13 of 68 (19%) cases of

MOC-31 is a cell surface glycoprotein of unknown function which is expressed on most normal and malignant epithelia. It was initially described for its utility in distinguishing metastatic adenocarcinoma and mesothelioma [9-12]. It is consistently expressed in cholangiocarcinoma and metastatic adenocarcinoma from a variety of sites, such as colorectum, pancreas, stomach, lung, breast and ovary. It yields a diffuse membranous pattern of staining in adenocarcinoma, which is easy to interpret [7]. Our case showed a diffuse and strong MOC-31 expression along with positive Heppar1, glypican, arginase and albumin ISH which in absence of masses elsewhere, essentially confirmed a hepatocellular origin. The only other tumor which entered the list of differentials was a Hepatoid Adenocarcinoma (HAC), which due to similar clinicopathologic features, closely resembles HCC and may even be indistinguishable from it.[2] HAC was first reported as an AFP producing tumor in 1970 [13] and Ishikura et, al. [14,15] in a report of seven AFP producing gastric adenocarcinomas, proposed the term hepatoid adenocarcinomas due to high AFP levels. Since then, it has been reported to arise in several other organs with stomach being the most common site. Because HAC bears a striking morphologic similarity to HCC in histology and IHC stains, it could be mistakenly diagnosed when liver tumors are the only initial finding, especially in regions with a high incidence of HCC [2]. HAC is a very aggressive neoplasm with metastasis in a high proportion of patients at the time of diagnosis. Lymph nodes and the liver are the most common sites of metastasis. Because of the high rate of metastasis and a disappointing response to chemotherapy [2], its distinction from HCC is crucial. Hence, in our case we stated the possibility of a metastatic HAC to the liver and recommended clinical correlation.

Conclusion

HCC can be difficult to diagnose, when it does not display a classic morphology or immunohistochemistry. A comprehensive panel of IHC stains should be used along with the clinical data and imaging findings to make the distinction from metastatic tumors (including HAC), as some cases of HCC can show uncommon features like MOC-31 expression, as we described.

Acknowledgement

None.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest.

References

- Karabork A, Kaygusuk G, Ekinci C (2010) The best immunohistochemical panel for differentiating hepatocellular carcinoma from metastatic adenocarcinoma. Pathol Res Pract 206: 572-577.

- Su JS, Chen YT, Wang RC, Wu CY, Lee SW, et al. (2013) Clinicopathological characteristics in the differential diagnosis of hepatoid adenocarcinoma: A literature review, World J Gastroenterol 19: 321-327.

- Lau SK, Prakash S, Geller SA, Alsabeh R (2002) Comparative immunohistochemical profile of hepatocellular carcinoma, cholangiocarcinoma, and metastatic adenocarcinoma. Hum Pathol 33: 1175-1181.

- Morrison C, Marsh W Jr, Frankel WL (2002) A comparison of CD10 to pCEA, MOC-31, and hepatocyte for the distinction of malignant tumors in the liver. Mod Pathol 15(12): 1279-1287.

- Porcell AI, De Young BR, Proca DM, Frankel WL (2000) Immunohisto-chemical analysis of hepatocellular and adenocarcinoma in the liver: MOC31 compares favorably with other putative markers. Mod Pathol 13: 773-778.

- Al-Muhannadi N, Ansari N, Brahmi U, Satir AA (2011) Differential diagnosis of malignant epithelial tumours in the liver: an immunohistochemical study on liver biopsy material. Annals of Hepatology 10(4): 508-515.

- Kakar S, Gown AM, Goodman ZD, Ferrell LD (2007) Best practices in diagnostic immunohistochemistry: hepatocellular carcinoma versus metastatic neoplasms. Arch Pathol Lab Med 131: 1648-1654.

- Proca DM, Niemann TH, Porcell AI, DeYoung BR (2000) MOC31 immuno-reactivity in primary and metastatic carcinoma of the liver: Report of findings and review of other utilized markers. Appl Immunohisto-chem Mol Morph 82: 120-125.

- Sosolik RC, McGaughy VR, De Young BR (1997) Anti-MOC31 A potential addition to the pulmonary adenocarcinoma versusmesothelioma immunohistochemistry panel. Mod Pathol 10: 716-711.

- Ordonez NG (1998) Value of the MOC-31 monoclonal antibody indifferentiating epithelial pleural mesothelioma from lungadenocarcinoma. Hum Pathol 29: 166-169.

- Edwards C, Oates J (1995) OV632 and MOC-31 in the diagnosis ofmesothelioma and adenocarcinoma: and assessment oftheir use in formalin-fixed and paraffin-wax embedded ma-terial. J Clin Pathol 48: 626-630.

- Ryan PJ, Oates JL, Crocker J, Stableforth DE (1997) Distinctionbetween pleural mesothelioma and pulmonary adenocarci-noma using MOC31 in an asbestos sprayer Respir Med 91: 57-60.

- Bourreille J, Metayer P, Sauger F, Matray F, Fondimare A, et al. (1970) Existence of alpha feto protein during gastric-origin secondary cancer of the liver. Presse Med 78:1277-1278.

- Ishikura H, Fukasawa Y, Ogasawara K, Natori T, Tsukada Y, et al. (1985) An AFP-producing gastric carcinoma with features of hepatic differentiation. A case report. Cancer 56: 840-848.

- Ishikura H, Kirimoto K, Shamoto M, Miyamoto Y, Yamagiwa H, et al. (1986) Hepatoid adenocarcinomas of the stomach: An analysis of seven cases. Cancer 58: 119-126.

-

Juhi D Mahadik, Melton H Fish, Shilpa Jain. Diffuse MOC-31 Expression in Hepatocellular Carcinoma: A Diagnostic Challenge. Acad J Gastroenterol & Hepatol. 1(5): 2020. AJGH.MS.ID.000521.

-

MOC-31, Hepatocellular carcinoma, Hepatoid adenocarcinoma, Immunohistochemistry, In-Situ Hybridization, Alpha-Fetoprotein, Liver tumors, Metastatic tumors, Viral infections, Metabolic syndrome, Alcohol, Cirrhosis

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.