Research Article

Research Article

Efficacy of Malva Sylvestris Extract (Mallolaxtm) for the Treatment of Functional Constipation and Associated Gastrointestinal Symptoms in Adults: A Pilot Study

Alessandro Colletti1,2, Marzia Pellizzato2, Valentina Citi3, Luciano Sangiorgio4, Giancarlo Cravotto1,2, Eva Navarro Sáez5 , Paolo Ballabio5, Alejandra Hernández Bueno5 and José Angel Maraňón5*

1Department of Pharmaceutical Science and Technology, University of Turin, 10125 Turin, Italy

2Italian Society of Nutraceutical Formulators (SIFNut), 31033 Treviso, Italy

3Department of Pharmacy, University of Pisa, 56126 Pisa, Italy

4Department of Pediatric Urology, SS. Antonio and Biagio and Cesare Arrigo Hospital, 15121 Alessandria, Italy

5Marenostrumtech SL, Spain

José Angel Maraňón, Marenostrumtech SL, Spain

Received Date:December 13, 2024; Published Date:January 07, 2025

Abstract

Background: Functional constipation, a highly prevalent condition worldwide, it is considered the result of a complex interplay between thegastrointestinal tract, the nervous system, the gut microbiome, along with diet and lifestyle factors. Within the dietary-behavioural change, the

intake of nutraceutical products has been shown to significantly improve the clinical picture of functional constipation, reducing the risk of side

effects of conventional therapies. In this context, the present pilot study aimed to assess the efficacy of a nutraceutical formulation containing a

specific Malva sylvestris extract (MALLOLAXTM), titrated on malvidin and malvidin-3-glucosides, in the management of functional constipation and

associated gastrointestinal symptoms.

Design: A three-arm, randomised controlled study was designed. 75 adults with low fibre intake and meeting the Rome IV criteria for functional constipation were recruited. The effect of the intake of Malva sylvestris extract (500 mg/day or 1000 mg/day of MALLOLAXTM capsules taken in water) during 3 weeks was compared vs placebo in the management of mild constipation.

Methods: Primary outcome was the change in frequency of complete spontaneous bowel movements (CSBM). Secondary outcomes were

stool consistency, gastrointestinal symptoms, quality of life and mood using the Patient Assessment of Constipation Symptoms (PAC-SYM), Patient

Assessment of Constipation Quality of Life (PAC-QoL), and Depression Anxiety and Stress Scale (DASS-21). Safety and tolerability were assessed

through. Safety and tolerability were evaluated through the self-reported adverse effect data collected at clinic interviews. The compliance of

treatments was monitored using a delivery of diary sheet.

Results: At the end of supplementation period CSBM were improved significantly in MALLOLAXTM groups. A notheworthy more significant

result were obtained in the higher dose of Mallolax extract group (p<0,0001). In addition, there was a significant improvement in stool consistency

(p<0,0001) and bowel movements (p<0,0001) in both active groups compared with placebo. A significant reduction in overall gastrointestinal

symptoms (PAC-SYM) and an improvement in quality of life (PAC-QoL) in Mallolax groups has also been shown. Moreover, there was a significant

reduction in mean score for depression, anxiety, and stress (DASS-21) for participants who received MALLOLAXTM 1 g/day, indicating a possible

dose-related effect on psychological functions.

Conclusions: The results showed that MALLOLAXTM formulations assumed for 21 days represents a safe and effective choice for the improvement

of functional constipation and associated symptoms in individuals reporting a low fibre intake. Future larger and longer randomised clinical trials

are needed to confirm the properties of the extract in functional constipation and to evaluate both efficacy and safety in medium- and long-term

treatments.

Abbreviations:Malva sylvestris; nutraceutical; malvidin, mucilages; chronic constipation; functional constipation

Introduction

Constipation, a well-known gastrointestinal disorder, was mentioned as a clinical entity for the first by the Egyptians in the 16th century A.C. [1]. It is the result of difficult stool passage and/ or infrequent stools which determine the unsatisfactory defecation [2]. Despite that constipation has been positively associated with different disorders such as intestinal cancer [3], cardiovascular diseases [4], cognitive impairment and neurological diseases [5], and it negatively impact on quality of life, its prevalence is still high, and it generates major healthcare-associated costs (estimated costs for constipation from 2017 to 2018 in UK National Health Service: £162 million) [6]. The metanalysis by Barberio et al. which included 45 trials and comprising 275.260 participants showed a prevalence of functional constipation of 15,3%, 11,2%, 10,4%, and 10,1% in studies which used the Rome I, Rome II, Rome III and Rome IV criteria respectively [7]. The aetiology of constipation is multifactorial. In particular, elderly, female gender, sedentary, reduced water and/ or dietary fibre intakes, hypothyroidism, assumption of certain drugs (e.g. non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, opioids, digoxin, glyceryl trinitrate, atorvastatin, furosemide and levothyroxine), colorectal cancer obstruction may play a role in the pathogenesis of constipation [8,9]. Constipation is generally classified in acute constipation, which symptoms that generally lasts less than a week, and chronic constipation [10]. Chronic constipation is associated with several factors, which enable the classification of the disorder into primary and secondary causes [11]. Primary causes include the slow transit or outlet obstruction, while the simple dehydration or inadequate fluid intake, medications, neurological disorders, metabolic disturbances, myopathic disorders and structural abnormalities are considered secondary causes of chronic constipation [12].

Functional constipation (FC) is a terminology proposed and defined by the Rome Foundation to help standardise the diagnosis of chronic constipation in the absence of physiological abnormality [13,14]. FC is considered the result of a complex interplay between the gastrointestinal tract, gut microbiome, nervous system, along with diet and lifestyle factors. It is characterised by a heterogeneous range of symptoms that could vary among patients, which include the persistently difficult and infrequent defecation associated with abdominal pain, bloating and/or incomplete evacuation, dry stools, excessive straining [15].

Despite that conventional treatments have shown to be effective in treating constipation, side effects are frequent [16]. In addition, among over-the-counter agents, stimulant laxatives (bisacodyl/ sodium picosulfate) are well established as first- or second-line treatments for constipation and although they have a reliable therapeutic effect, safety concerns still exist, particularly with longterm use, even for the increased risk of tolerance and dependence [17]. Several nutraceutical agents including aloe, senna, rhubarb, buckthorn, and cascara known for its anthraquinone glycoside content are also considered contact laxatives and should not be recommended for long periods (>4 weeks) of treatment [18]. In this context, other botanical supplements may prove to be useful as adjuvants in FC even for long-term treatment periods.

Malva sylvestris L. is a Mediterranean flowering plant belonging to the Malvaceae family which is traditionally used as an antiulcer, laxative and anti-haemorrhoid, besides of its culinary applications as a food [19]. Aerial parts of M. sylvestris have been showed to have antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, laxative, wound-healing and immunomodulatory properties [20]. The phytocomplex of M. sylvestris contains several chemicals with different biological activities, including polysaccharides, fatty acids, carotenoids, polyphenols, ascorbic acid, and tocopherols [21]. M. sylvestris has been described as an intestinal stimulant and an effective laxative for children by Boulos [22] and Lim [23]. Both in vitro and in vivo studies showed the strong protective effect of M. sylvestris extract on constipation, which has been attributed not only to its antioxidant activity, but also to its ability to stimulate gastrointestinal motility and intestinal secretion [24]. However, depending on the amount of plant matter consumed, section of the plant used, and method of extraction M. sylvestris could profoundly vary its healthy effects. In this context, MALLOLAXTM is a standardised and titrated extract obtained from M. sylvestris which contains more than 5% of polyphenols (malvidin) and more than 30% of mucilages.

The present study aimed to assess the efficacy of a standardised nutraceutical formulation containing a specific M. sylvestris extract (MALLOLAXTM), titrated on mucilages, malvidin and malvidin-3- glucosides, in the management of FC and associated gastrointestinal symptoms.

Materials and Methods

Study design and participants

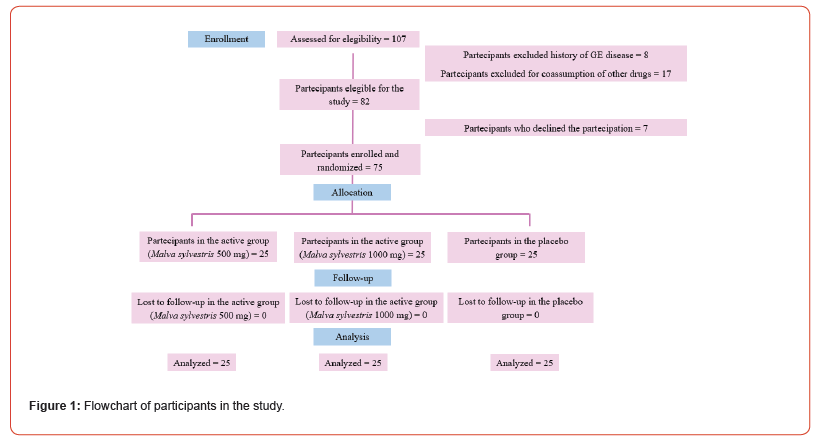

This was a pilot, three-arms, double-blind, study. 75 Volunteers with previously diagnosed functional constipation, were randomized in 3 differnte groups. A formulation containing a specific Malva sylvestris extract 500 mg/day (MallolaxTM), Malva sylvestris extract 1000 mg/day (MallolaxTM), or placebo for three weeks were suministrated. The study population included 75 individuals (flowchart described in Figure 1) enrolled through the “Department of Drug Science and Technology” of University of Turin. The inclusion criteria included participants with age between 25-65 years, which self-reporting functional constipation, meeting the Rome IV criteria for functional constipation, and who consumed less than 4 serves of vegetables, fruit and wholegrains combined per day.

Rome IV criteria includes two or more of the following for the last three months: straining more than 25% of defecations, lumpy or hard stools (BSFS type 1 or 2) more than 25% of defecations, sensation of incomplete evacuation more than one-fourth (25%) of defecations, sensation of anorectal obstruction/blockage more than one-fourth (25%) of defecations, manual manoeuvres to facilitate more than one-fourth (25%) of defecations, fewer than three spontaneous bowel movements per week [25].

The exclusion criteria were the following: history of gastrointestinal disease and/or previous gastrointestinal surgery (e.g. gastric bypass, intestinal resection, colorectal surgery), inflammatory bowel disease, gastroesophageal reflux disease, dysphagia, secondary cause of constipation, medications affecting bowel function (antibiotics, antacids, proton pump inhibitors, stool softeners, laxatives, or fibre supplements) at the time of recruitment or within the previous four weeks. Any medical or surgical condition that makes the patient’s adherence to the study protocol complex or inconstant, women who were pregnant or breastfeeding, allergies or intolerances to the active ingredient or excipients were also exclusion criteria. Patients were excluded from the study if they had missing data or recall visits, or they reported the use of nontrial drugs during the observation period.

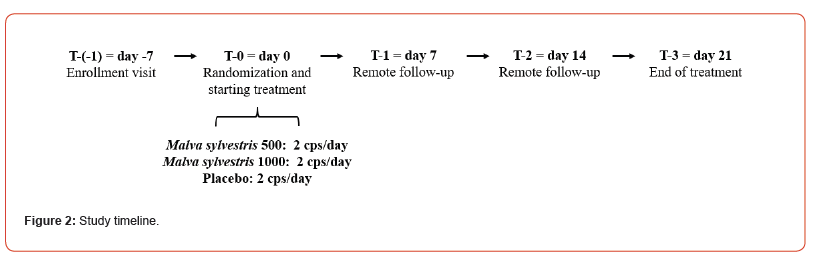

Supplementation

After the informed consent signature during the enrolment visit (T-1), volunteers were asked to complete a 3-day food diary to investigate their eating habits and specifically the dietary fibre intake. In addition, the medical history, drugs or supplements use were recorded. At the time of randomization (T-0), every patient was randomly allocated to the three study groups, in order to receive MALLOLAXTM (Malva sylvestris L. dry extract; titration: >5% of total polyphenols, 30% of mucilages; dosage per day: 500 or 1000 mg), or placebo. 2 capsules were taken daily, starting at T=0 and continued for 21 days. For the entire duration of the study, patients were instructed to take the assigned treatment at approximately the same time each day, preferably in fasted state.

Volunteers were directly monitored at the beginning (T-0) and at the end (T-3) of the treatment period. Before to every monitoring, a 3-day food diary was completed. At T-1 and T-2 volunteers were supported remotely by a specialist in food science, to self-report the frequency of complete spontaneous bowel movements (CSBM) and stool consistency over the previous 7 days, in addition to evaluate the compliance, and the tolerability of the products. Standardised validated questionnaires (Patient Assessment of Constipation – Symptoms (PAC-SYM) [26], Patient Assessment of Constipation – Quality of Life (PAC-QoL) [27] and Depression Anxiety and Stress Scale (DASS-21) [28]) were supplied during T-0 and T-3 to assess the degree of symptoms participants experienced and the effect on quality of life and depression, anxiety, and stress.

The study timeline is described in detail in Figure 2.

Supplements containig mallolax were manufactured and packaged in accordance with Quality Management System ISO 9001:2015. Groups randomization was performed using computergenerated codes. Participants and investigators were blinded to the group assignment. The alphanumeric codes (X, Y, Z) of randomization were kept closed inside an envelope kept in the locked drawer of the main investigator’s desk. It was opened at the end of the study by the principal investigator.

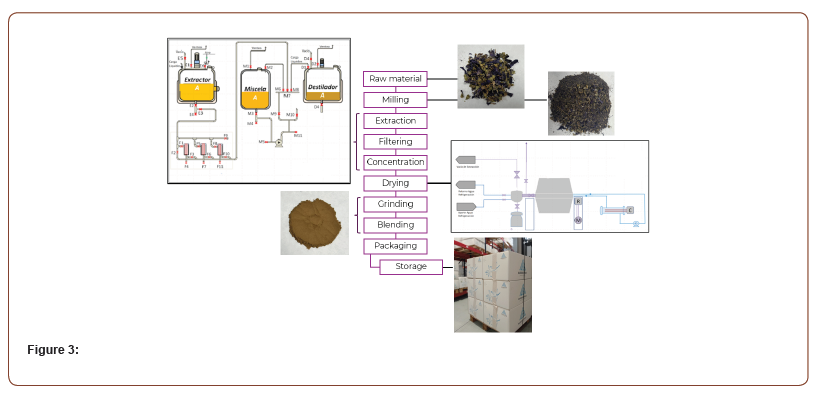

Product preparation

After preliminary studies at laboratory scale to define the extraction process and the optimal parameters for the concentration of the active ingredients of interest, the process is carried out on an industrial scale. The raw material must be according to the specified properties within acceptable ranges to ensure the repeatability of the process and homogeneity of the product. In the extraction phase, the maceration of the raw material in the solvent mixture is carried out by adjusting temperature, pressure, agitation and optimal time. In the next phase, the extraction liquid containing the active ingredient of the raw material is filtered through a filter system of at least 5 microns using pressure and vacuum. The filtered liquid is concentrated until obtaining a determined ratio and Brix. The residual solvent will be recovered to be reused in the next extraction phase. To obtain the dry extract it is used a rotary system with heat and vacuum, achieving low temperature drying. The dry extract is grinded to adjust the physical properties of the product according to the specification and homogenized prior to packaging.

The scheme depicted in Figure 3 summarizes the preparation steps of MALLOLAXTM.

Assessment of the efficacy

The primary outcome was the change in number of complete spontaneous bowel motions (CSBM) per week over 21 days of treatment. Secondary outcomes included the stool consistency and both the quality of life and symptoms of the enrolled subjects.

The Bristol Stool Chart, a scale ranging from 1 = very hard small pebbles, to 7 = entirely liquid, was used as the visual tool for the assessment of the stool consistency at T-0, T-1, T-2 and T-3 [29]. Patient symptoms, quality of life, and mood were assessed at the beginning (T-0) and end (T-3) of the three-week treatment period.

Quality of life was assessed by using the Patient Assessment of Constipation – Quality of Life (PAC-QoL) questionnaire. It consists of 28 items divided into four subscales (worries and concerns -11 items, psychosocial discomfort -8 items, treatment satisfaction -5 items, and physical discomfort -4 items), and it evaluates the impact of symptoms with responses from 0 (symptom absent) to 4 (very severe) [30]. Patients’ symptoms were evaluated through the Patient Assessment of Constipation – Symptoms (PAC-SYM), which is questionnaire characterised by 12 items, with three symptom subscales: stool (five items), abdominal (four items), and rectal (three items). All items are scored ranging from 0 (symptom absent) to 4 (very severe) [31].

The Depression Anxiety and Stress Scale (DASS-21), a 21-item quantitative measure of distress in terms of depression (7 items), anxiety (7 items), and stress (7 items), was used to assess the mood, with scores from 0 ‘did not apply to me at all’ to 3 ‘applied to me all the time’ [32].

Assessment of the safety and tolerability

Safety and tolerability were evaluated through the self-reported adverse effect data collected at clinic interviews. The compliance of treatments was monitored using a delivery of diary sheet.

Statistical analysis

Personal data and physiological/pathological anamnesis were detected at the enrolment visit (T-1), while treatment compliance only in T3.

A sample size of 25 patients per group was found necessary to fit a statistical model for analysing the differences among the study groups.

Data were incrementally entered during the study period into an electronic sheet (Microsoft, Redmond, WA), double checked for errors, and then processed using the GraphPad Prism 8.0.2 software version for Windows. A descriptive analysis of each of the variables was made. The demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients were analysed using One-way ANOVA, followed by Dunnet post-test was applied for the statistical analysis. A significance level <0.05 was considered statistically significant for all tests conducted.

Results

One hundred seven subjects were evaluated for the eligibility of the study. Eight subjects were excluded for the history of gastroenterological diseases. Seventeen subjects were excluded for the co-assumption of nontribal drugs/supplements. Finally, the study population included 75 volunteers (female N=51, male N=24), with age ranged from 25-65 years (average 47 years), who completed the study.

The reported dietary fibre intake through the 3-day diary was less for most participants across all groups (n = 70; 93%), compared to the recommended daily intake. All groups presented an average intake of fibres of 17 g (p=0,37), ranging from 8 to 24 for people in Mallolax1000 group, 7 to 25 for people in Mallolax500 group and 8 to 26 for people in placebo group. At T-3, the reported average daily fibre intake was 19 g (6–26 g) in Mallolax1000, 18 g (7–27 g) in Mallolax500, and 14 g (7–26 g) in placebo, which were not significantly different (p= 0,13).

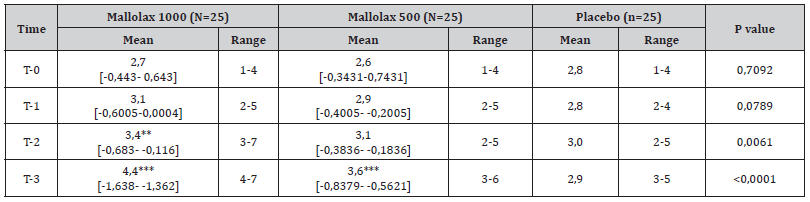

During the enrolment visit, participants self-reported passing no more than 3 stools per week on average over the past 3 months. At T-(-1), the week before the starting treatment, 66 patients (88%) reported three or fewer CSBM, while nine participants (12%) passed 4 motions. The number of CSBM gradually increased each week during the study period, as indicated in Table 1. In particular, subjects of Malva 1000 group benefited a significant improvement in CSBM at T-2 (average CSBM/week: from 2,9 at baseline to 3,4) and T-3 (CSBM/week: 4,4) (p<0,01 and p<0,001 respectively vs placebo), while participants of Malva 500 group reached the statistical significance at T3 (CSBM/week: from 2,6 at baseline to 3,6, p<0,001 vs placebo). Non-significant differences were observed in placebo group from all the period of treatments.

Table 1:The mean and range in number of CSBM per week for participants who were randomized to take Mallolax 500, Mallolax 1000 or placebo once daily, for 21 days. Number of CSBM were examined during the week prior to the supplementations, and then day 1–7 (T-1), day 8–14 (T-2), and day 15–21 (T-3) after starting treatment. Data are expressed as the mean and range, with the probability (p) of the means being different according to one-way ANOVA, followed by Dunnet post-test.

One-way ANOVA, followed by Dunnet post-test was applied for the statistical analysis. Means ± SD are reported, followed by the 95% Confidential Interval of difference vs Placebo [95,00% CI of diff.]. The asterisks indicate the statistical significance vs Placebo: P < 0,05 (*); P < 0,01 (**); P < 0,001 (***).

Regarding the stool consistency, subjects reported a numerical code for each CSBM using the Bristol Stool chart (from type I to VII). The sum of the codes was divided by the sum of the number of CSBM for each of the treatment weeks. Despite that stool consistency of single individuals varied considerably in all groups (from type I to type V), a constant improvement was observed in both active groups (Mallolax 1000 group average stool consistency: 2.6 (T-0), 2.8 (T-1), 3.1 (T-2), 3.4 (T-3); Mallolax 500 group: 2.7 (T-0), 2.8 (T- 1), 2.8 (T-2), 3.1 (T-3); Placebo: 2.8 (T-0), 2.6 (T-1), 2.7 (T-2), 2.6 (T-3) (p<0,001).

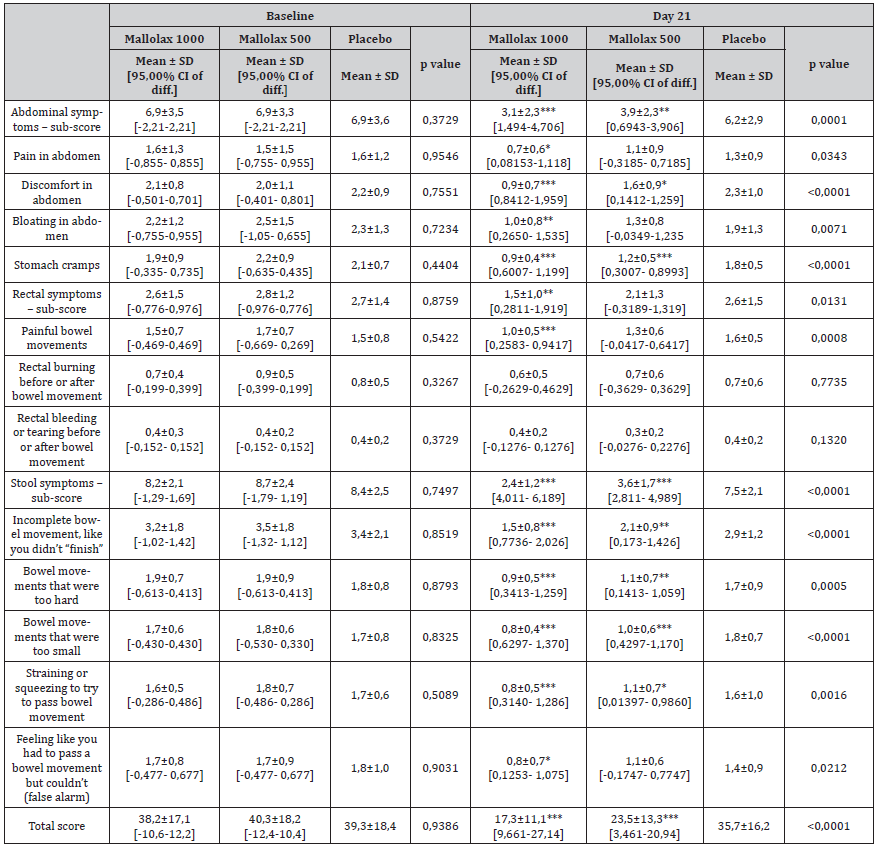

Table 2 describes the PAC-SYM score between all groups. At T-3 there was a significant improvement in total PAC-SYM score from Mallolax groups compared with placebo (P < 0,001 for both active groups). Abdominal symptoms were reported in all groups at baseline. After 21 days of supplementation participants of both Mallolax groups reported a general improvement in abdominal symptoms compared with placebo (Mallolax500 P < 0,01 and Mallolax1000 P < 0,001 respectively). In particular, abdominal pain, discomfort, bloating and cramps were significantly improved in Mallolax1000 group, while subjects in Mallolax500 group showed a significantly improvement of discomfort and cramps. Rectal symptoms were less frequently reported compared with abdominal symptoms. However, an overall improvement of rectal symptoms sub-score was observed in patients of Mallolax1000 group (p<0,01 compared with placebo). Specifically, a reduction of painful bowel movements was reported in Mallolax1000 group (p<0,001 vs placebo). Stool symptoms were also improved in the active groups (p<0,001 for both compared with placebo). In particular, there was a significantly lower mean score by subjects in Mallolax groups in terms of bowel movements that were too hard (p<0,001 for Mallolax1000 and p<0,01 for Mallolax500) or too small (p < 0.001 for both), straining or squeezing (p<0,001 for Mallolax1000 and p<0,05 for Mallolax500), and incomplete bowel movement, like you didn’t “finish” squeezing (p<0,001 for Mallolax1000 and p<0,01 for Mallolax500). Feeling like you had to pass a bowel movement but couldn’t, it improved only in Mallolax1000 group (p<0.05). This led to a significant difference in stool symptoms sub-score between groups at 21 days (p = 0.022). In this context, the total score of PACSYM was significantly reduced in the active groups (Mallolax1000: from 38,2 to 17,3; Mallolax500: from 40,3 to 23,5; p<0,001 vs placebo for both).

Table 2:Patient Assessment of Constipation – Symptoms (PAC-SYM) total score and sub-scores for subjects randomized to ake the Mallolax500 (n = 25), Mallolax1000 (n = 25) and placebo (n = 25). Questionnaires were completed at the beginning and the end of the 21-day treatment period. Data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (mean ± SD), with the probability (p) of the means being different according to one-way ANOVA, followed by Dunnet post-test.

One-way ANOVA, followed by Dunnet post-test was applied for the statistical analysis. Means ± SD are reported, followed by the 95% Confidential Interval of difference vs Placebo [95,00% CI of diff.]. The asterisks indicate the statistical significance vs Placebo: P < 0,05 (*); P < 0,01 (**); P < 0,001 (***).

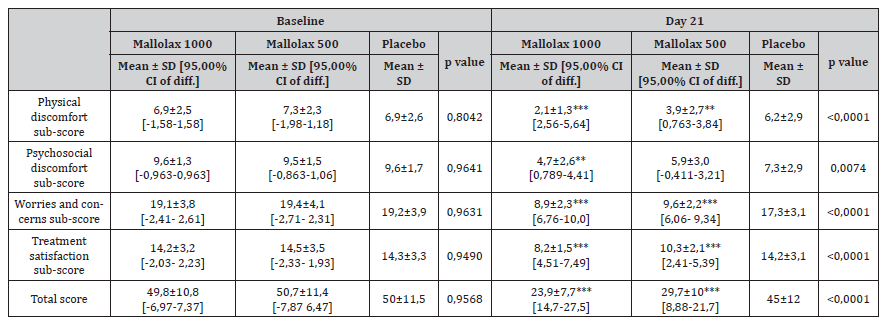

Table 3 describes a similar average of total quality of life score (PAC-QoL) at baseline amomg the three groups (p = 0.957). At the end of the study, total score was significantly improved in both active groups (p<0,001), indicating that FC negatively impacts on quality of life. In detail, physical discomfort, worries and concerns were improved in both active groups. Psychosocial discomfort improvement was solely reported at the Mallolax1000 group. Moreover, the score for active treatments satisfaction were significantly lower at the end of the study, highlighting its superiority compared to the placebo group (p < 0.001 both).

Table 3:Patient Assessment of Constipation – Quality of Life (PAC-QoL) scores for participants randomized to the Mallolax formulations and placebo groups. Questionnaires were completed at the beginning and the end of the 21-day treatment period. Data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (mean ± SD), with the probability (p) of the means being different according to one-way ANOVA, followed by Dunnet post-test.

One-way ANOVA, followed by Dunnet post-test was applied for the statistical analysis. Means ± SD are reported, followed by the 95% Confidential Interval of difference vs Placebo [95,00% CI of diff.]. The asterisks indicate the statistical significance vs Placebo: P < 0,05 (*); P < 0,01 (**); P < 0,001 (***)..

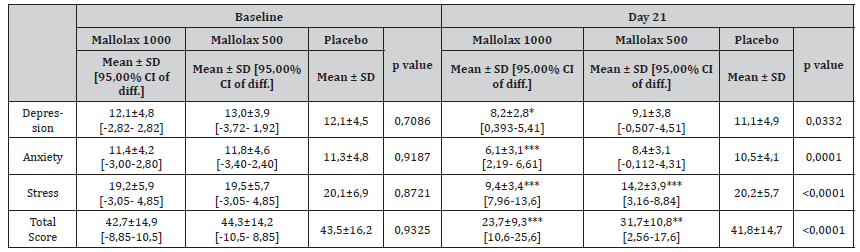

Table 4 indicates the mean and range for depression, anxiety and stress scores on the DASS-21 questionnaire before (baseline) and after 21 days of treatments. At T-0, only 16 of the individuals (21%) scored in the normal range for the depression, anxiety and stress sections. This percentage improved at the end of treatment (48 subjects = 64%). At T-3 a significant reduction in mean score for depression and anxiety was observed in Mallolax1000 group (p<0,05 and p<0,001 respectively, compared with placebo). Moreover, perceived stress improved in both active groups (p<0,001 for both compared with placebo), highlighting the possible association between the improvement of FC and the reduction in stress.

Table 4:Mean depression, anxiety and stress scores on the DASS-21 questionnaire before (baseline) and after 21 days of the supplementation period for participants. Data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (mean ± SD), with the probability (p) of the means being different according to one-way ANOVA, followed by Dunnet post-test.

One-way ANOVA, followed by Dunnet post-test was applied for the statistical analysis. Means ± SD are reported, followed by the 95% Confidential Interval of difference vs Placebo [95,00% CI of diff.]. The asterisks indicate the statistical significance vs Placebo: P < 0,05 (*); P < 0,01 (**); P < 0,001 (***).

Discussion

The present study demonstrated that the assumption of a titrated M. sylvestris extract, for 21 days, had a positive impact on functional constipation, by increasing the frequency of bowel motions, improving the stool consistency and quality of life, and reducing the associated gastrointestinal symptoms. The effect on intestinal regularization reported in this clinical trial is in agreement with the results by Elsagh et al, which showed that M. sylvestris L. flowers aqueous extract syrup (1 g/day) for four weeks improved the frequency of constipation symptoms and stool forms (all P values <0.01) compared with placebo [33].

The mechanisms of action of M. sylvestris have not yet been fully established but seem to be correlated to its phytocomplex with pleiotropic properties (Figure 1). In particular, the presence in the phytocomplex of polyphenols such as anthocyanins (e.g. malvidins, delphinidin, quercetin), flavonols and flavones (e.g. gossypetin, hypolaetin) showed higher antioxidant activity compared to other compounds [34]. In this regard, the role of oxidative stress in FC has been investigated. Several studies highlight that chronic constipation leads to oxidative injury with overproduction of free radicals and reduction in the endogenous antioxidant system (antioxidant enzymes such as catalase (CAT), glutathione peroxidase (GPx) and superoxide dismutase (SOD)), thus worsening the oxidative stress. The imbalance between reactive oxygen species and antioxidant systems seems to play an important role in the development of FC, causing intestinal dysmotility and establishing a vicious cycle [35]. In this context, the study by Jabri et al. [36] confirmed the relationship between constipation induced by loperamide and oxidative stress: the inhibition of peristalsis was followed by oxidative damage expressed as increased levels of hydrogen peroxide and malondialdehyde and reduce levels of glutathione and antioxidant enzymes (SOD, GPx, CAT). This data agreed with clinical trials in which prolonged constipation in children was associated with increased oxidative stress [37] and growth retardation [38]. Mallolaxtm extract contains also mucilages which are well recognized as prebiotics that can positively affect human gut microbiota, improving FC. The potential of mucilages as prebiotics is attributed to its high content of soluble heteropolysaccharides which are considered the main progenitor of short chain fatty acids (SCFAs), which promote the growth of eubiotic gut bacteria [39]. Mucilages presents also laxative effects through its high-water absorbability which results in an osmotic effect, and its ability to regulate the cholinergic pathway, stimulating the gastrointestinal motility and intestinal secretion [40].

The presence of Malvidin glucosides in Mallolaxtm extract may positively impact on FC by restoring the gut microbiota and reducing both oxidative stress and inflammation. In this context, malvidin showed to restore the Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio repressed by dextran sulfate sodium (DSS), reduce the abundance of pathogenic bacteria, such as Ruminococcus gnavus, and reverse several key inflammatory mediators, including sphingolipid metabolites, in DSS colitis mice [41].

However, the arsenal of different Malva sylvestris extracts developed and commercialized in the market, could be associated with a high variability of clinical effects. Therefore, it is important that the benefits of a nutraceutical product do not solely depend on the right choice of the active ingredient and the dosage of administration, but also on a correct biopharmaceutical formulation, optimizing the extraction processes in order to preserve its characteristics. In this context, the standardization of the extraction techniques of Mallolaxtm respecting the concept of the “circular economy”, as well as the titration of the extract in mucilages and polyphenols represents a key point to guarantee the reproducibility of the effects.

Compliance with Mallolaxtm treatment was excellent. No side effects were reported during the study. This study has some limitations such as the relatively small sample size with few enrolled patients and the lack of the evaluation of blood markers of oxidative stress and inflammation. Despite that the sample size was powered to measure the primary outcome of CSBM, the small cohort might limit the generalisability of the findings to the broader FC population. Moreover, symptoms scores and questionnaires used in this trial represent validated instruments even if the results should be interpreted with the natural limitations present for selfreporting measures. For these reasons, further research is required to investigate the long‐term effects of Mallolaxtm on FC.

Conclusions

A supplement containing Mallolaxtm a standardised and titrated extract obtain from the aerial parts of M. sylvestris, assumed for 21 days, demonstrated to be efficient in the improve of complete spontaneous bowel motions and alleviating constipation symptoms in individuals with functional constipation who reported a low fibre intake. Further longer randomised clinical trials with larger sample sizes are needed to confirm this effects in long-term supplementation period.

References

- Ebbell B (1937) The Papyrus Ebers: the greatest Egyptian medical document. Levin & Munksgaard pp. 30-32.

- Bassotti G, Usai Satta P, Bellini M (2021) Chronic Idiopathic Constipation in Adults: A Review on Current Guidelines and Emerging Treatment Options. Clin Exp Gastroenterol 14: 413-428.

- Sundbøll J, Thygesen SK, Veres K, Liao D, Zhao J, et al. (2019) Risk of cancer in patients with constipation. Clin Epidemiol 11: 299-310.

- Zheng T, Camargo Tavares L, D'Amato M, Marques FZ (2024) Constipation is associated with an increased risk of major adverse cardiac events in a UK population. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 327(4): H956-H964.

- Leta V, Urso D, Batzu L, Weintraub D, Titova N, et al. (2021) Constipation is Associated with Development of Cognitive Impairment in de novo Parkinson's Disease: A Longitudinal Analysis of Two International Cohorts. J Parkinsons Dis 11(3): 1209-1219.

- Bowel Interest Group (2019) The cost of constipation. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepato 4: 811.

- Barberio B, Judge C, Savarino EV, Ford AC (2021) Global prevalence of functional constipation according to the Rome criteria: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 6(8): 638-648.

- Yurtdaş G, Acar Tek N, Akbulut G, Cemali Ö, Arslan N, et al. (2020) Risk Factors for Constipation in Adults: A Cross-Sectional Study. J Am Coll Nutr 39(8): 713-719.

- Werth BL, Christopher SA (2021) Potential risk factors for constipation in the community. World J Gastroenterol 27(21): 2795-2817.

- Camilleri M, Ford AC, Mawe GM, Dinning PG, Rao SS, et al. (2017) Chronic constipation. Nat Rev Dis Primer 3(1): 1-19.

- Andrews CN, Storr M (2011) The pathophysiology of chronic constipation. Can J Gastroenterol 25(Suppl B): 16B-21B.

- Jani B, Marsicano E (2018) Constipation: Evaluation and Management 115(3): 236-240.

- Kilgore A, Khlevner J (2024) Functional Constipation: Pathophysiology, evaluation, and management. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 60 (Suppl 1): S20-S29.

- Andrews CN, Storr M (2011) The pathophysiology of chronic constipation. Can J Gastroenterol 25(Suppl B): 16B-21B.

- Bharucha AE, Lacy BE (2020) Mechanisms, Evaluation, and Management of Chronic Constipation. Gastroenterology 158(5): 1232-1249.e3.

- Chang L, Chey WD, Imdad A (2023) AGA-ACG Clinical Practice Guideline: Pharmacological Management of Chronic Idiopathic Constipation. Am J Gastroenterol 118(6): 936-954.

- Rao SSC, Brenner DM (2021) Efficacy and Safety of Over-the-Counter Therapies for Chronic Constipation: An Updated Systematic Review. Am J Gastroenterol 116(6): 1156-1181.

- Whorwell P, Lange R, Scarpignato C (2024) Review article: do stimulant laxatives damage the gut? A critical analysis of current knowledge. Therapeutic Advances in Gastroenterology 17: 17562848241249664.

- Jabri MA, Wannes D, Hajji N, Sakly M, Marzouki L, et al. (2017) Role of laxative and antioxidant properties of Malva sylvestris leaves in constipation treatment. Biomed Pharmacother 89: 29-35.

- Batiha GE, Tene ST, Teibo JO, Shaheen HM, Oluwatoba OS, et al. (2023) The phytochemical profiling, pharmacological activities, and safety of malva sylvestris: a review. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 396(3): 421-440.

- Gasparetto JC, Martins CA, Hayashi SS (2012) Ethnobotanical and scientific aspects of Malva sylvestris L.: a millennial herbal medicine. J Pharm Pharmacol 64: 172–189.

- Boulos L (1983) Medicinal plants of North Africa. Reference publications, Algonac, pp. 110.

- Lim T (2014) Viola tricolor. Edible Medicinal and Non-Medicinal Plants. Springer, pp, 808-817.

- Jabri MA, Wannes D, Hajji N, Sakly M, Marzouki L, et al. (2017) Role of laxative and antioxidant properties of Malva sylvestris leaves in constipation treatment. Biomed Pharmacother 89: 29-35.

- Aziz I, Whitehead WE, Palsson OS, Törnblom H, Simrén M (2020) An approach to the diagnosis and management of Rome IV functional disorders of chronic constipation. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 14(1): 39-46.

- L Frank, L Kleinman, C Farup, L Taylor, P Miner Jr (1999) Psychometric validation of a constipation symptom assessment questionnaire Scand. J. Gastroenterol 34(9): 870-877.

- P Marquis, C De La Loge, D Dubois, A McDermott, O Chassany (2005) Development and validation of the patient assessment of constipation quality of life questionnaire Scand J Gastroenterol 40(5): 540-551.

- SH Lovibond LPF (1995) Manual for the depression anxiety stress scales, Psychology Foundation of Australia, Sydney, NSW.

- SJ Lewis, KW Heaton (1997) Stool form scale as a useful guide to intestinal transit time Scand J Gastroenterol 32(9): 920-924.

- P Marquis, C De La Loge, D Dubois, A McDermott, O Chassany (2005) Development and validation of the patient assessment of constipation quality of life questionnaire Scand J Gastroenterol 40(5): 540-551.

- L Frank, L Kleinman, C Farup, L Taylor, P Miner Jr (1999) Psychometric validation of a constipation symptom assessment questionnaire Scand J Gastroenterol 34(9): 870-877.

- SH Lovibond LPF (1995) Manual for the depression anxiety stress scales, Psychology Foundation of Australia, Sydney, NSW.

- Elsagh M, Fartookzadeh MR, Kamalinejad M, Anushiravani M, Feizi A, et al. (2015) Efficacy of the Malva sylvestris L. flowers aqueous extract for functional constipation: A placebo-controlled trial. Complement Ther Clin Pract 21(2): 105-111.

- Marañón JA, Nañez Valdivieso J, Torrecillas Mosquero V, Hernández-Bueno A, Arce Aix I, et al. (2023) Benefits of MALLOLAX® on the Restoration of the Antioxidant Defenses in Intestinal Mucosal Barrier Depleted by Constipation. Am J Gastroenterol Hepatol 4(1).

- Mousavi T, Hadizadeh N, Nikfar S, Abdollahi M (2020) Drug discovery strategies for modulating oxidative stress in gastrointestinal disorders. Expert Opin Drug Discov 15(11): 1309-1341.

- Jabri MA, Wannes D, Hajji N, Sakly M, Marzouki L, et al. (2017) Role of laxative and antioxidant properties of Malva sylvestris leaves in constipation treatment. Biomed Pharmacother 89: 29-35.

- Zhou JF, Lou JG, Zhou SL, Wang JY (2005) Potential oxidative stress in children with chronic constipation. World J Gastroenterol 11(3): 368-371.

- Chao HC, Chen SY, Chen CC, Chang KW, Kong MS, et al. (2008) The Impact of Constipation on Growth in Children. Pediatr Res 64(3): 308-311.

- GT Macfarlane, H Steed, S Macfarlane (2008) Bacterial metabolism and health-related effects of galacto-oligosaccharides and other prebiotics. J Appl Microbiol 104: 305–344.

- Kassem IAA, Joshua Ashaolu T, Kamel R, Elkasabgy NA, Afifi SM, et al. (2021) Mucilage as a functional food hydrocolloid: ongoing and potential applications in prebiotics and nutraceuticals. Food Funct 12(11): 4738-4748.

- Liu F, Wang TTY, Tang Q, Xue C, Li RW, et al. (2019) Malvidin 3-Glucoside Modulated Gut Microbial Dysbiosis and Global Metabolome Disrupted in a Murine Colitis Model Induced by Dextran Sulfate Sodium. Mol Nutr Food Res 63(21): e1900455.

-

Alessandro Colletti, Marzia Pellizzato, Valentina Citi, Luciano Sangiorgio, Giancarlo Cravotto,et.all. Efficacy of Malva Sylvestris Extract (Mallolaxtm) for the Treatment of Functional Constipation and Associated Gastrointestinal Symptoms in Adults: A Pilot Study. Acad J Gastroenterol & Hepatol. 4(2): 2025. AJGH.MS.ID.000581.

-

Malva sylvestris; nutraceutical; malvidin, mucilages; chronic constipation; functional constipation

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

Track Your Article

Refer a Friend

Advertise With Us

Feedback

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.irispublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.irispublishers.com.

Best viewed in