Research Article

Research Article

28 Day Randomized Double-Blind Placebo Controlled Trial using Pre-Polymerized Cross-Linked Sucralfate Barrier (Esolgafate) for Erosive GERD

Ricky Wayne McCullough1,2*

1Translational Medicine Clinic and Research Center, USA

2Department of Internal Medicine and Emergency Medicine, Warren Alpert Brown University School of Medicine, USA

Ricky Wayne McCullough, Translational Medicine Clinic and Research Center, Storrs Connecticut, USA.

Received Date: March 16, 2020; Published Date: April 01, 2020

Abstract

Background: Treatment of erosive gastroesophageal reflux disease (eGERD) centers on control of acid pH using proton pump inhibitors (PPI), histamine 2 receptor antagonists (H2RA) and antacids (AA). However, the presence of bile and serine proteases in gastric refluxate, not addressed by PPI, H2RA or AA, is suspected to be associated with onset of Barrett’s esophagus and rise of esophageal adenocarcinoma. Pre-polymerized sucralfate barrier therapy (PPSBT) recognized first by US FDA as a medical device has enhanced bio adherence and blocks access of acid and non-acid irritants to the mucosa.

Aim: To evaluate the efficacy of mucosal protection by PPSBT for the treatment of erosive GERD.

Methods: In a 28 day statistically powered, multi-center randomized double-blind placebo controlled trial, 19 patients with eGERD were randomized to receive PPSBT or placebo. Antacids were available to each group for breakthrough pain. Treatment effect on erosions and eGERD symptoms (heartburn & reflux sensation) were evaluated. Adverse events were assessed.

Results: For patients taking PPSBT, 89% and 78% had relief of heartburn and reflux respectively compared to 25% and 12.5 % of those on placebo. Complete healing occurred in 89% taking PPSBT compared to 25% of those on placebo. No adverse events occurred.

Conclusions: Enhanced mucosal protection by PPSBT demonstrates effective symptom control and erosion healing in patients with eGERD. Acid-indifferent cytoprotection from acid, bile and serine proteases by PPSBT may be a useful adjunct in management of eGERD, and a return to the past for the future.

Summary Box:

What is already known about this subject:

a) Acid irritation is believed to be the sole concern for managing erosive GERD

b) Erosive GERD is best managed by proton pump inhibitors

c) Sucralfate has no role in the therapeutic management of erosive GERD

What are the new findings:

a. Acid, bile acids and proteases are co-equal irritants for erosive GERD

b. Proton pump inhibitors do not address bile acids and proteases

c. Standard sucralfate is too weak to address acid, bile acids and proteases

d. FDA recognized pre-polymerized sucralfate barrier therapy effectively excludes acid, bile acids and proteases from esophageal mucosa in erosive GERD

Keywords: Polymerized sucralfate; Barrier therapy; Erosive GERD; Randomized controlled trial

Introduction

The first regulated use of sucralfate in humans was in 1968 in Japan [1], followed by the US in 1982 [2], both for the treatment of duodenal ulcer. Advent of sucralfate suspension in the US [3] in 1992 supported an undercurrent of off-label use of sucralfate for erosive gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). However, sucralfate was relegated to the sidelines of therapeutic options for GERD by 1994, due to sucralfate’s lack of substantial clinical effect, compared to the efficacy of ranitidine, famotidine, nizatidine (each histamine-2 receptor agonists (H2RA) and the introduction of omeprazole, the first proton pump inhibitor (PPI) which was more effective than H2RA’s for GERD. In 2005, the US FDA recognized an alternative form of sucralfate, pre-polymerized sucralfate [4] and then 9 years later in the 2014 Digestive Disease Week (DDW) of American Gastroenterological Association, data from two randomized controlled trials was published in abstract form and showed that pre-polymerized cross-linked sucralfate was safe and effective for both erosive GERD and non-erosive gastroesophageal reflux disease (NERD) [5]. Outcomes of each randomized controlled trial demonstrated unexpectedly large and statistically significant treatment efficacy.

Of the two trials reported in the 2014 DDW, one was a 42 patient 7 day randomized 3-way active controlled trial assessing the rapidity of relief and healing of erosive GERD. In that study, previously reported in this journal [6], PPSBT was found more effective with rapid healing of eGERD and an equivalence in symptom relief. The second trial was 28 day randomized controlled, double-blinded involving both erosive GERD and NERD patients. This report provides the narrative regarding the 19 erosive GERD patients of that trial using pre-polymerized cross-linked sucralfate versus placebo. The remaining trial data submitted elsewhere [7] was a 42 patient 28 day randomized double blind placebo controlled trial for undifferentiated nonerosive reflux disease (NERD). Undifferentiated NERD is a cohort of patients with functional heartburn, esophageal hypersensitivity and classic NERD. Symptoms and signs from gastroesophageal reflux disease, whether erosive or non-erosive, arise from mucosal reaction to a backwash of gastric refluxate. Physiologic reflux is asymptomatic and presumably occurs without histomorphological consequences. However, according to some [8,9], the presence of heartburn sensation likely heralds the advent of histomorphologic changes. Whether physiologic reflux (a) causes heartburn episodes (esophageal reflux hypersensitivity syndrome), (b) is unrelated heartburn episodes (functional heartburn) or (c) whether abnormally frequent reflux causes heartburn with grossly intact mucosa (NERD) or grossly eroded mucosa (erosive GERD), histomorphologic alterations in the esophageal mucosa are identifiably present [8, 9]. Furthermore, symptom perception has been linked to the loss of mucosal integrity [10-12]. Therefore, even patients with esophageal reflux hypersensitivity syndrome have a physiologic breach of the epithelium on a cellular level (sense it can be perceived by the patient) [12,13], even though there may be no grossly visible histological changes. These mucosal alterations (both cellular and histological) are facilitated by a mucosal immune reaction [14-17] involving pro-inflammatory cytokines [18, 19] and can present as dilated intercellular spaces within the esophageal epithelium [8, 20]. Dissolved conjugated bile is equally culpable as acid [21-24], can cause intercellular dilation [25, 26], and is generally responsible for both mast-cell mediated upregulation of pain receptors in the lower esophagus [27] as well as cytokine-driven inflammation from reflux [19]. These alterations in immuno-homeostasis and changes in histomorphology give rise to higher transepithelial permeability and lower extracellular impedance observed in the esophagus of patients with functional heartburn, GERD and NERD [12].

Regardless of its clinical classification, clearly symptomatic esophageal reflux is a barrier integrity problem. Therefore, effective barrier therapy is a logical alternative step. First generation sucralfate prescribed at the normal 14mg per kilogram dose cannot amass a gastroesophageal barrier effective enough to provide timely symptomatic relief for NERD or timely healing and relief of erosive GERD. At ingestion, regular sucralfate (tablet or suspension) is biologically insert, polymerized by gastric acid into its active biological form [28]. Then following ingestion and polymerization, it is excreted from the colon chemically unchanged within 48 hours in an amount that is 95-98% the original dose [29]. Due to its poor clinical performance and the ready availability of acid-controlling therapies, regular sucralfate is excluded from most management guidelines for GERD [30-33]. Yet findings from early basic science research on sucralfate portended an alternative view, a view that posed sucralfate as a potentially transformative therapy. From 1982 through 1995, in parallel to approved clinical uses of sucralfate were translational medicine research on the physiologic basis for sucralfate’s cytoprotective healing. Early observations, well chronicled by Hollander and Tygat [34], pertain to the nature of sucralfate interaction with the mucosa. There are at least three reasons why sucralfate was deemed an all-purpose cytoprotectant for the GI tract. Firstly, its binding target is not bare epithelium, but mucin within the mucus gel of the epithelial lining [35-37]. Secondly, this contact with mucus gel strengthens the gel’s integrity in a dose dependent fashion [38], resulting in a multifold enhancement of viscosity, a 60% increase in its hydrophobicity which in turn causes decreased permeability of hydrogen ions (acid) [39], of cations (e.g., calcium) [40], of bile acids [41] and inhibits endogenous proteases (pepsin) [42] and exogenous (h.pylori) mucolytic proteases [43,44]. Thirdly, associated with partially dissolved and partly polymerized (that is, large focal concentrations of) sucralfate, endoscopic examination revealed near-immediate histologic, ultrastructural and functional changes within the mucosal epithelium, attributed solely to physical contact with sucralfate [45,46]. These changes diminished circumferentially at radial distances from the partially dissolved tablet. By sucralfate’s non-chemical physical engagement of mucin covering the epithelium, from 5 to 60 minutes, there is increased mucin release, increased luminal release of prostaglandin E2 and signs of epithelial cell renewal generally centered at the physical site of contact with partially polymerized, partially dissolved, but firmly adherent, sucralfate tablet [45].

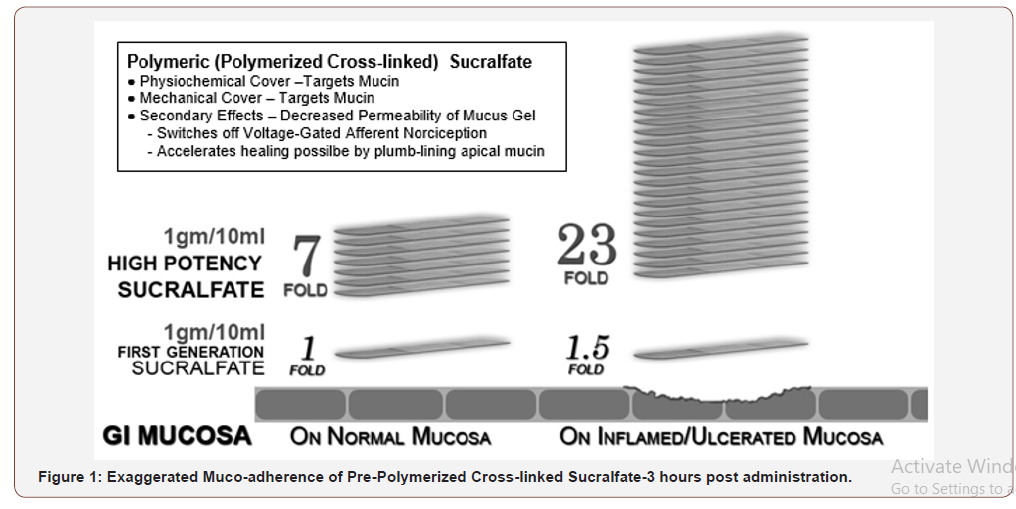

The reason these rapid and dramatic mucosal changes observed at that time but did not translate into significant clinical outcomes is that experimental doses used in these investigations were 5-10 fold that of the 14mg per kilogram dose generally permitted by drug regulators for clinical practice, hence at regular dosing, significantly less surface concentrations of sucralfate can be achieved. This implies that an adequate mucosal barrier can be achieved if the surface concentration of sucralfate is augmented several fold beyond that possible with regulatory dosing of 14mg per kilogram. Gastric acid polymerized sucralfate can physically enhance properties of mucin within the mucus gel, if sufficient increased oral doses could be given or tolerated. However, at regulatory doses of 14mg per kilogram per dose four times daily, gastric acid polymerized sucralfate is quantitatively inadequate and structurally vulnerable to water hydration, diluting it and thereby limiting surface concentrations of sucralfate. Alternative polymerizations of sucralfate that are more resilient to water hydration permit augmented accumulation of sucralfate within the mucus gel. At three hours post-administration, pre-polymerized cross-linked sucralfate barrier therapy (PPSBT) maintains a sucralfate concentration that is 800% greater on normal mucosa and 2,400% greater on injured/eroded mucosa (discussed in Methods). This innovation enables an administered dose of PPSBT (containing 1.5 of sucralfate) to achieve mucosal concentrations of sucralfate similar to those likely to have occurred in the basic science studies of Tarnawski, et al. [45] and Slomiany, et al. [38, 39] wherein sucralfate doses was more than 5 fold the standard dose of 14mg per kilogram.

This report provides the narrative of data published previously in abstract form [5] and demonstrates the clinical effects of prepolymerized sucralfate barrier therapy on erosive GERD in a controlled setting.

Methods

Objectives and hypotheses

The main objective of this trial was to assess the effectiveness and safety of pre-polymerized sucralfate barrier therapy suspension in the healing and symptomatic relief of erosive GERD. In this trial placebo was used as a comparator which is optimal in testing the efficacy of any new treatments [47].

Ethics and trial registration

The trial was registered at Medical Research Council of Bangladesh (BMRC) [48] who provided institutional review of its protocol. Patients provided written informed consent to participate in the trial in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

ISO 14155 compliant clinical investigation of medical device

For scientific transparency in the evaluation of medical devices [49], the current study was designed to be compliant with current ISO 14155 standards which addresses good clinical practice for the design, conduct, recording and reporting of clinical investigations carried out in human subjects [50]. The current trial assesses the safety and performance of Esolgafate as a barrier therapy medical device for GERD. Safety of sucralfate-based products is well documented and has been established since 1968 [29]. Identified herein are rules and procedures for data collection, statistical power of the study and rationale of sample size. Recruitment of participants, randomization, concealment and allocation of interventions were performed in a manner to minimize bias, ensure collection of objective and credible data and support the overall goal of protecting patients’ safety and well-being.

Study design

The study was designed as a randomized double-blind placebocontrolled trial with allocation ratio 1:1. Each of the two study arms received identically mark bottles containing a white suspension identical in color and flavor. One intervention contained prepolymerized sucralfate barrier therapy (PPSBT) suspension, while the other, placebo, contained no sucralfate.

Setting and participants

Recruitment of participants took place in three medical center clinics where patients received primary and specialty medical care services. Eleven gastroenterologists conducted patient recruitment.

Inclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria for male or females, aged between 18 to 58 years, included dyspeptic symptoms (heartburn which included regurgitant reflux, postprandial chest discomfort) occurring 2-7 times per week for 3 months leading up to the study. There was a 7 day run in period following upper endoscopy. Included patients demonstrate ability to follow protocol instructions and complete self-administered questionnaire. All participants had the right to withdraw from the study at any time with no obligation to give reason for their decision.

Exclusion criteria

Excluded were individuals with Barrett’s esophagus, peptic strictures, peptic ulcer disease or those requiring motility altering drugs. Also excluded were individuals requiring medication for diabetes, hypertension or dyslipidemia. Individuals with alarm signs: difficulty swallowing, painful swallowing, gastrointestinal bleeding or anemia, weight loss or history of cardiac chest pain, history of upper GI tract surgery, of cancer of head and neck and upper GI tract were excluded. Patients with known hypersensitivity to ingredients of the test treatments were excluded. Women who knew they were pregnant or were breastfeeding were excluded. Those with difficulty following protocol instructions (diary maintenance, keeping follow-up appointments etc) were excluded.

Randomization criteria

Participants were assigned by simple randomization into one of 2 groups, PPSBT or placebo. Simple randomization was aided by use of a random number table wherein patients who had been assigned a two digit number from 01 to 70 plus were sequentially assigned to one of two treatment groups based on the first digits of the random number table being either even or odd.

Interventions

The intervention under investigation include suspension of pre-polymerized cross-linked sucralfate (PPSBT) barrier therapy and placebo which was identical to PPSBT in color, favor and ingredient but contained no sucralfate. Both were manufactured by Pharmaco Laboratories Private Limited of Dhaka Bangladesh for Mueller Medical International (MMI). Each intervention was dispensed by a single hospital pharmacy associated with the medical centers responsible for recruitment. The pharmacology of PPSBT is relatively new and differs significantly from nonpolymerized sucralfate. The latter form of sucralfate is regulated as a drug because of required in situ polymerization by gastric acid following ingestion, that is, biologically inert sucralfate.

Polymerization and cross-linking process for PCLS involves use of cationic organic acid and therefore more resistant to hydration than sucralfate polymerized by gastric acid. Figure 1 shows that 3 hours post-administration, PCLS achieves and maintains a surface concentration of sucralfate that is 7 fold (or 800%) greater on normal mucosa and 23 fold (or 2400%) greater on acid-injured mucosa compared to gastric-acid polymerized sucralfate [51]. Dosing volume for each intervention was 15ml taken twice daily for 28 days. This volume of PPSBT contained 1.5grams of sucralfate while the same volume of placebo contained no sucralfate.

Concomitant medications

Except for the use of antacids, participants were not permitted use of any anti-peptic medications. Two 300ml bottles of aluminum hydroxide/magnesium hydroxide (400mg/400mg per 10ml) were provided to each participant every 7 days of the 28 day trial whether or not antacids were used. All used and unused bottles of antacids were collected at completion of trial.

Allocation concealment and blinding

Consecutive randomization numbers were given to participants and the study product was packaged and signed by consecutive numbers according to the randomization list from which participant numbers were generated. Bottles distributed to participants contained either pre-polymerized sucralfate barrier therapy (PPSBT) suspension or the suspension vehicle for PPSBT without sucralfate. Each intervention was identical in color and flavor. Participants, outcome assessors and person responsible for the statistical analysis were blinded to the intervention until completion of the study. Personal information about potential and enrolled participants was accessible only to the researchers involved in the trial.

Compliance

Participants were required to bring any remaining study product (including empty bottles) and diary to the study site at the end of the intervention period. Compliance with the study protocol was checked by counting the number of bottles left unused. Generally, participants receiving less than 75% of recommended doses would be considered as noncompliant [52].

Outcome measures

There were two primary outcome measures, symptomatic relief (of heartburn and reflux sensation) and healing. There were two secondary outcomes. The first was the emergence of adverse events. The second pertain to reliance on use of antacids as measured by count of used and unused antacid bottles assessed on a weekly basis. Whether required or not, three 300ml bottles of aluminum hydroxide/magnesium hydroxide antacid (400mg/400mg per 10ml) were provided per participant per week at the beginning of Week 1,2,3 and 4. At end of each week patients returned used and unused bottles of antacids for examination and a replacement pair of bottles were supplied.

Primary outcome – symptomatic relief

One primary outcome was the relief of heartburn and reflux sensation. The number and severity of each symptom episode were recorded by participant in a dairy as the episode occurred. Severity was assessed using a patient graded symptom intensity 5 point Likert scale, where 0 = absence of symptom, 1 = minimal awareness of symptom, easily tolerated, 2 = awareness of symptom, bothersome but tolerable without impairment of daily living or sleep, 3 = very bothersome interfering but not impairing daily living or sleep and 4 = intolerable and impairing daily living or sleep. A quantitative score for heartburn (HB), reflux (RR) and retrosternal discomfort was calculated by multiplying the number of such episodes by severity on the Likert scale. Using patient diaries, examiners averaged resultant quantities on a per day basis to arrive at a daily symptom specific score. The quantitative analysis was performed at end of Week 0, 1, 2, 3 and 4. An outcome was deemed positive if there was 50% improvement in the daily total symptom scores (a multiple of daily symptom frequency and symptom severity) in 28 days of the trial.

Primary outcome – healing

Another primary outcome was healing of erosions. Endoscopies were preformed 7 days prior to start of interventions and on the 29th day following 28 days of intervention use. The Hetzel-Dent grading system [53] was used to assess GERD erosions. Complete healing occurred with endoscopic absence of erosions on Day 29, a Hetzel-Dent Grade 0 or 1, and was rated as complete healing. Partial healing was improvement by at least 1 Grade but still above Hetzel- Dent Grade 1. No healing was noted when there was complete absence of improvement in grade of erosions on Day 29.

Secondary outcome - adverse events

Adverse events (AEs) were collected Day 29 prior to endoscopy. An AE was defined as a negative medical event occurring during the 28 day study period, whether or not related to the study or interventions. Severe AE (SAE) were negative medical events that resulted in death, was life-threatening occurrence, required emergency room care, hospitalization or severe (or persistent) disability or incapacitation.

Secondary outcome – antacid use

Reliance on use of antacids was a secondary outcome. Whether required or not, three 300ml bottles of aluminum hydroxide/ magnesium hydroxide antacid (400mg/400mg per 10ml) were provided per participant per week at the beginning of Week 1,2,3 and 4. At end of each week patients returned used and unused bottles of antacids for examination and a replacement pair of bottles were supplied.

Power calculation

The primary outcome of the trial is symptomatic relief and healing of erosive GERD. Table 1 provides parameters for sample size calculation. Based on the Cochrane meta-analysis involving medical treatments for short term management of reflux esophagitis [54] healing and symptomatic relief using a proton pump inhibitor (PPI) or histamine-2 receptor antagonist (H2RA) occurred roughly 80% of the time compared to a placebo response of 15%. To be relevant in the management of eGERD, PPSBT should be at least as effective as PPI or H2RA. Placebo was anticipated to have an outcome similar to that reported in Khan, et al. [54]. Thus to detect similar differences in this trial having a placebo rate of 15% and a PPSBT rate of 80%, where the alpha error is 0.05 and beta error is 0.2 for a power of 0.80, then the sample size for the study should be 16 participants with 8 participants per treatment arm. Assuming a 20% loss to follow-up and the incidence of erosive GERD among patients with dyspepsia, 72 participants were recruited.

Table 1:Statistical Sample Size for Dichotomous Endpoints with Two Treatment Arms.

Statistical analysis

All analysis was conducted on an intention-to-treat basis, including all patients in groups to which they were randomized for whom outcomes would be available (including withdrawals and lost to follow-ups). Descriptive statistics were used to summarize baseline characteristics. The Student t test was used to compare mean values of continuous variables for approximating a normal distribution. The chi-square test was used to compare percentages. Differences between study groups were considered significant when the p value was less than 0.05, when 95% CI for RR did not include 1.0 or when the 95% CI for mean difference did not include 0. All statistical tests were two tailed and performed at the 1% level of significance.

Result

Conduct of the trial

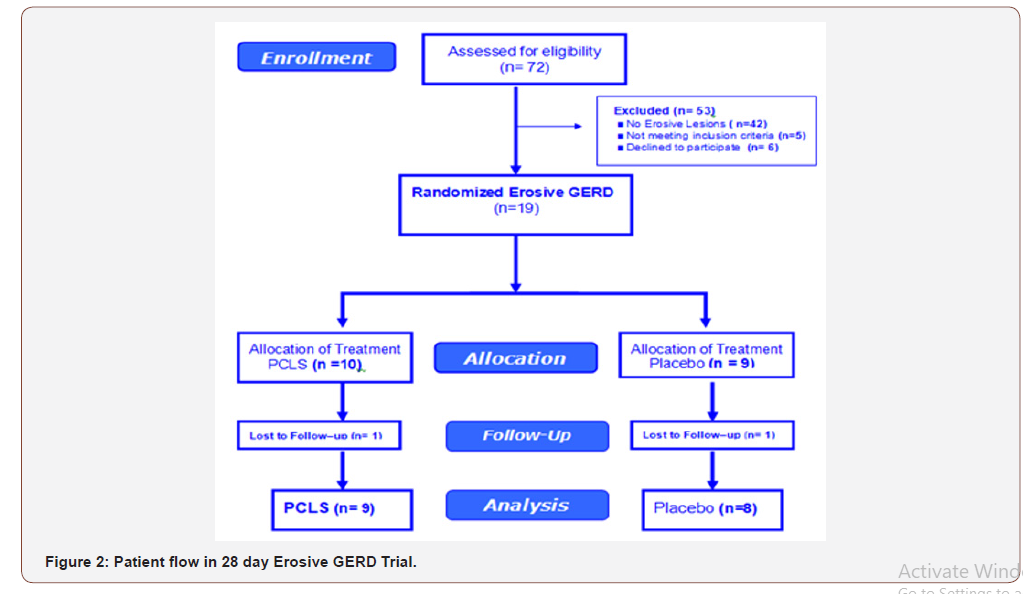

A total of 72 patients with dyspepsia recruited by eleven gastroenterologists were assessed for endoscopic eligibility for the trial resulting in 42 being excluded due to absence of erosions, that is, a Hetzel-Dent score of Grade 0 to 1. Another 6 declined to participant and 5 had pre-existing exclusionary conditions (Figure 2). The remaining 19 patients were randomized to 1 of 2 treatment arms.

Adequacy of sample size

The study was appropriately powered. Based on the statistical power applied to the study design, 8 participants per treatment arm were required. All treatment arms had at least 8 participants per intervention entered into data analysis for a total of 17 participants.

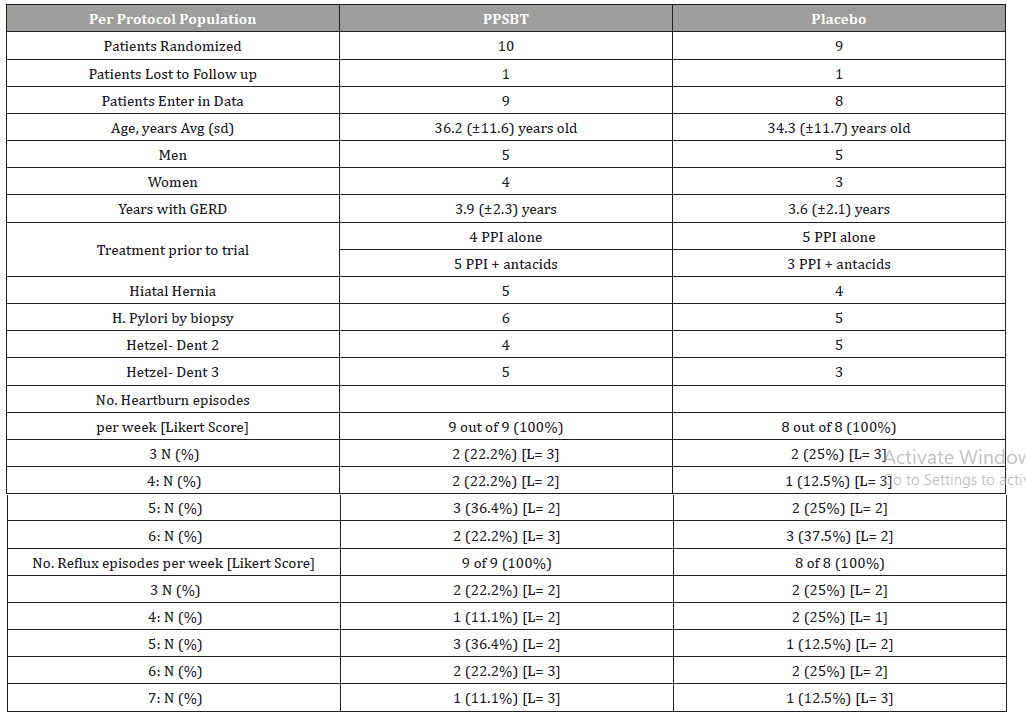

Participants

Patients randomized into two treatment arms were comparable in age, gender, days per week of heartburn, reflux sensation and severity of erosions (Table 2). Patients in PPSBT treatment arm suffered from eGERD for an average of 3.9 ± 2.3 years, while those in placebo arm suffered eGERD for 3.6 ± 2.1 years. The PPSBT and placebo group experienced heartburn and reflux discomfort at the same frequency, 100%. Prior to the trial, participants were managed with a PPI or PPI plus antacids. Patients were similarly matched for presence to hiatal hernia and helicobacter pylori. Helicobacter pylori was assessed by endoscopic biopsy from the antrum near pyloric ring and along the greater curvature of the corpus.

Table 2:Baseline characteristics of Randomized Patients.

As shown in Table 2, while the majority of eGERD symptoms could be sorted into 2 categories (heartburn and reflux sensation), not all patients exhibited each category equally. An outcome was deemed positive if there was 50% improvement of the daily total symptom score which is a multiple of daily symptom frequency and symptom severity (Likert scale) over 28 days of the trial.

Compliance of the trial

Compliance across treatment arms was acceptable for both PPSBT (90%) and placebo treatment arm (88.9%) due to 1 patients lost to follow up from each group.

Primary outcomes

Relief of heartburn and reflux

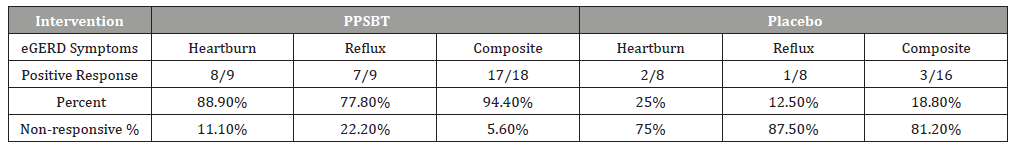

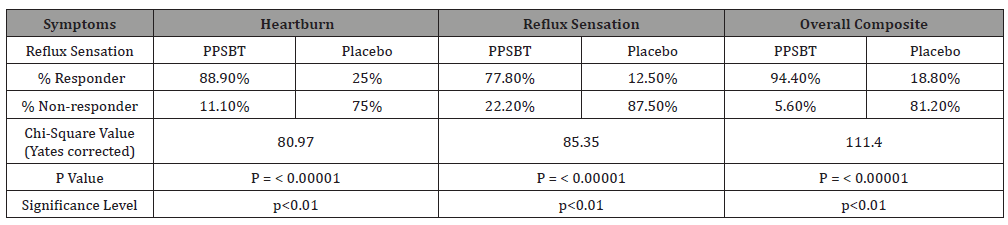

Table 3 shows 28 day symptomatic relief of two categories of eGERD symptoms using PPSBT and placebo. A positive outcome was achieved by 50% improvement of daily total symptom score at the end of 28 days.

Table 3:Symptom Outcome for eGERD over 28 days.

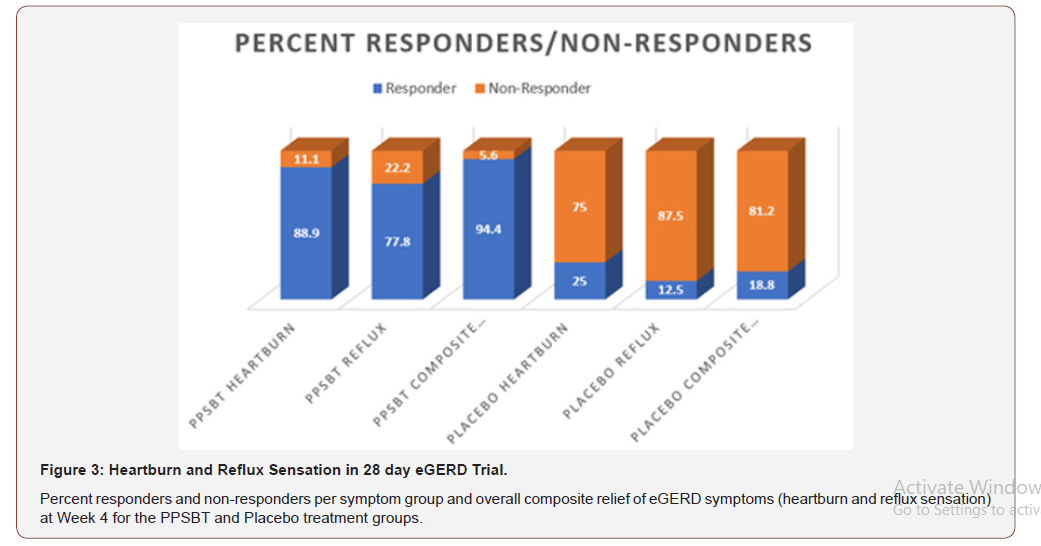

The dependence of symptom improvement using PPSBT was evaluated by chi-square analysis (Table 4). Yates corrected value supported that the relief of heartburn and reflux sensation in patients with eGERD was associated with the use of PPSBT but not with the use of placebo. The degree of dependence on PPSBT versus placebo for symptom relief in eGERD is illustrated in Figure 3. At the end of 28 days, patients using PPSBT were observed to have significant reduction in heartburn, reflux sensation or composite of the same, at 88.9%, 77.8% and 94.4% respectively. This was better than that observed in patients on placebo where relief from heartburn and reflux sensation was 25% and 12.5% with a composite relief of 18.8%.

Table 4:Symptom Outcome for eGERD over 28 days.

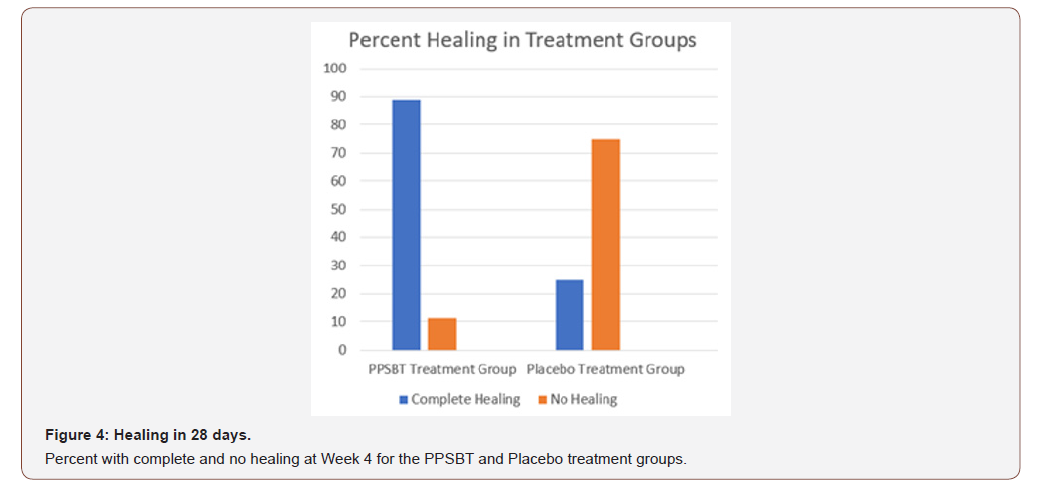

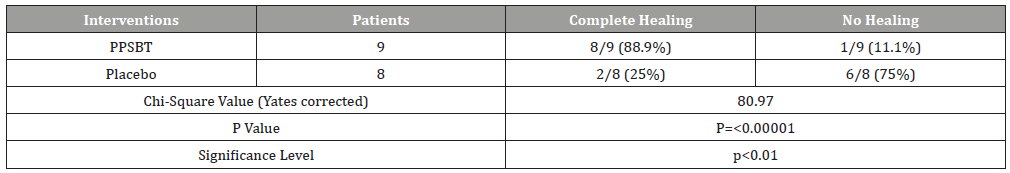

Healing of erosions

Outcome related to healing of erosions is in Tables 5. Notable in 28 days, substantial complete healing occurred in the PPBST group (88.9%), while minimal complete healing occurred in placebo group, namely 12.5%. Data in Table 5 is illustrated in Figure 4.

Table 5:Healing following 28 day Treatment with PPBST and Placebo.

Secondary Outcomes

Safety and adverse events

All patients took multiple doses of each intervention and were included in the safety analysis. Results are presented for the intent to treat population. No patients reported adverse events in either PPSBT or placebo group.

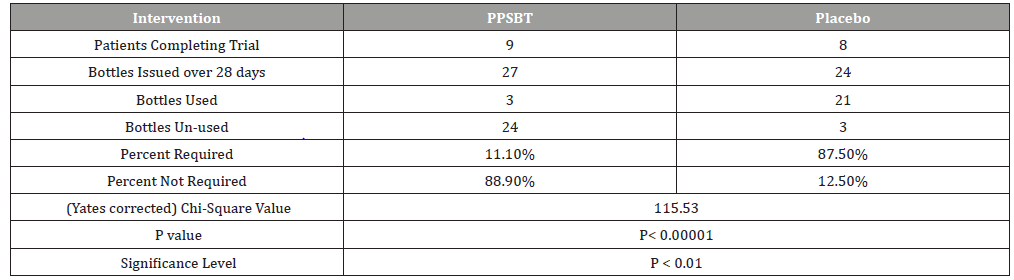

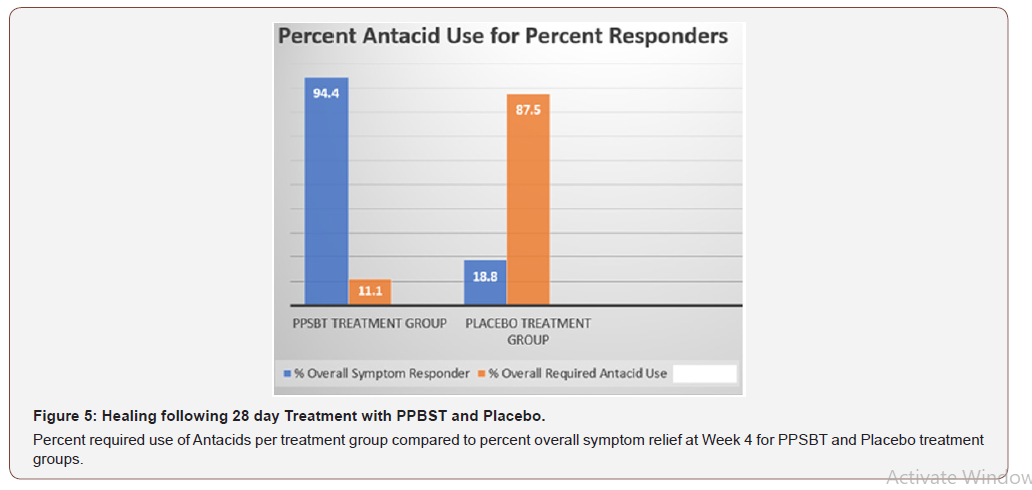

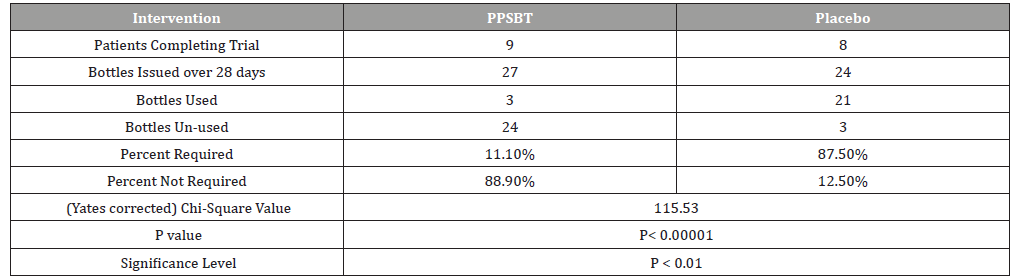

Dependence on antacids

The dependence of symptom relief on the use of antacids in patients using PPSBT and placebo was evaluated by chi –square analysis (Table 6). Yates corrected chi-square value supported independence of PPSBT-associated relief of required use of antacids to supplement symptom mitigation. Use of placebo was associated with high use of antacid with 87.5% of dispensed bottles being used to alleviate eGERD symptoms (Table 6 and Figure 5). Three 300ml bottles of aluminum hydroxide/magnesium hydroxide antacid (400mg/400mg per 10ml) were provided per participant at the beginning of Week 1,2,3 and 4, whether required or not. At end of each week patients returned used and unused bottles of antacids for examination and a replacement pair of bottles were supplied. Antacid use in PPSBT group was minimal with only 11.1% of dispensed bottles being used. Antacid use in placebo treatment group was 7.9 fold greater than that in PPSBT group. PPSBT-associated symptomatic relief was largely independent of antacid use. Figure 5 illustrates the data in Table 6, the percent use of supplied antacid together with overall composite symptom relief in patients in both treatment groups.

Table 6:Antacid Use During 28 day Trial.

Discussion

This study on symptomatic relief and healing of erosive GERD was a 28 day randomized placebo-controlled double-blind trial assessing the efficacy and safety of pre-polymerized sucralfate barrier therapy. Efficacy was assessed by endoscopic examination of healing and by quantifying relief of heartburn and reflux sensation in patients with eGERD. PPSBT is a medical device and any clinical evaluation should be ISO 14155 compliant. The trial was properly powered with an appropriate sample size of 19 patients (16 required), 10 patients in the PPSBT treatment arm and 9 in placebo arm. The trial was conducted transparently with no significant compliance issues among participants. The defining traits in each patient group (gender, age, years with disease, presence of h.pylori, hiatal hernia, endoscopic findings, severity of symptoms) were roughly equivalent for each treatment arm. Therefore, by ISO 14155 standards meaningful conclusions on outcomes can be made. As to outcomes, use of pre-polymerized sucralfate barrier therapy was associated with over 94% composite symptom (heartburn and reflux) relief and 89% healing rate over 28 days. This is slightly better than PPI in terms of symptom control and healing when compared to placebo in a control setting [54]. Dependence on antacids for rescue or breakthrough symptoms was low (11%) in patients using pre-polymerized cross-linked sucralfate compared to those using placebo (88%). No adverse events were reported throughout the trial, which may be a function of the low number of participants. Though not reported in narrative format here, similar outcomes were observed for pre-polymerized sucralfate in a 7 day head to head study with omeprazole, ranitidine and antacids for relief and healing of erosive GERD [6]. In that 7-day eGERD study there was complete healing and 20% partial healing in the pre-polymerized sucralfate group (1.5 gram bid) compared to 30% complete healing and 10% partial healing using omeprazole (20mg bid) and no healing in 7 days using ranitidine (150mg bid) and antacids (30ml of 400mg/400mg/10ml of aluminum hydroxide/magnesium hydroxide). Also in a 28 day randomized controlled trial of patients with NERD, heartburn, reflux sensation and retrosternal discomfort was 90%, 83% and 88% relieved by pre-polymerized sucralfate compared to placebo rates of 11%, 25% and 20% respectively [7].

So, is the use of pre-polymerized sucralfate barrier therapy of reflux disease a “back to the future” event, a revisit of sucralfate? Answering this question necessitates some background review.. Sucralfate was first approved for human use in Japan in 1968 [55] and then later in the US in 1982 [2] as a tablet then in 1992 as a suspension [3]. From 1968 to 2019 there are more than 214 registered brands regulated in 69 countries [56]. Whether tablet or suspension, prior to administration, sucralfate is biologically inert, requiring polymerization by gastric acid (a chemical reaction within the body) for conversion into its clinically active form wherein it uses a physical mode of action to establish a clinical effect. Transmission electron micrographs, scanning electron micrographs and unfixed freeze-fractured, and freeze-dried electron micrographs demonstrate the sucralfate preferentially avoids denuded epithelial cells. It binds to mucous gel in a manner so as to span its depth from luminal interface of loose mucin (in a decreasing gradient) downward reaching the more firmly adherent mucin layer which covers the apical epithelium [37]. Aside from class –based gastrointestinal drug-drug interactions (aluminum based products), sucralfate has been relatively safe [29] and is regulated as an over-the-counter heartburn agent by 13 national agencies representing 1.67 billion people [57]. Despite having a pure physical mode action bio-inert sucralfate is regulated as a drug because it requires a chemical reaction within the body – gastric acid polymerization - for conversion into a bioactive clinically relevant form. Sucralfate engages mucin without chemically altering mucin and itself remains chemically unchanged, with 98% of the original dose being excreted from the colon. If present in mucin gel in significant concentrations, such as concentrations achievable by 5-7 times the allowed 14mg per kg dose, then sucralfate, within the resultant sucralfate-mucin electrostatic engagement, is associated with real time histologic, ultrastructural and functional changes occur within the esophageal epithelium [38,39,45]. Bioinert sucralfate used in doses similar to those of basic science experiments would likely create a bezoar, or sucralfate concretions within the human GI tract [58]. Yet using endoscopic biopsies, Tarnawski, et al. [45] clearly demonstrated that a 1 gram dissolving gastric-acid polymerized sucralfate tablet lying in contact with a 5 square centimeter area of intact human gastric mucosa will in real time, elicit positive histologic, ultrastructural and functional changes in the mucosa. So achieving high mucin gel concentrations of polymerized sucralfate is a relevant path to a future wherein certain formulations of sucralfate may conceivably offer meaningful management options for eGERD.

In response to a device application involving topical use of sucralfate polymerized with hydrochloric acid prior to administration and use, the US FDA ruled that if bio-inert sucralfate is polymerized during manufacture and prior to patient use, then the resultant pre-polymerized sucralfate is a medical device [4]. Sucralfate polymerized with mineral acid is vulnerable to water hydration, while sucralfate polymerized with organic acid and subsequently cross-linked, as is PPSBT, is more resilient and is much less vulnerable to water hydration. More importantly, and more relevant to a ”Tarnawski et al type of sucralfate enteric mucosal reaction, is that sucralfate polymerized in a manner similar to that used for PPSBT, achieves augmented surface concentrations of sucralfate, which are concentrations similar to those illustrated in Figure 1. It cannot be over emphasized that the entirety of sucralfate’s clinical effect rests solely in the surface concentrations achieved and maintained within the mucin gel compartment of the mucosal epithelial barrier. A 14mg /kg dose of bio-inert sucralfate is not clinically meaningful for symptomatic relief of erosive GERD. However, as this trial and others have shown [5,6,7], a 14mg/ kg dose of PPSBT which is 7 to 23 times more potent in terms of concentrations of sucralfate achievable in the mucin gel layer, is associated with clinical effects significantly improved over those reported with bio-inert gastric-acid polymerized sucralfate.

Comparatively speaking, elevated sucralfate surface concentrations have resulted in outsized treatment effects. The best know sucralfate outcome for erosive GERD was reported by Vermeijden, et al. [59]. Using 4 grams daily of standard bio-inert sucralfate, patients required 56 days to achieve 80% symptomatic relief and 68% healing. In this trial, pre-polymerized sucralfate barrier achieved 94% symptomatic relief (though not measured in the same manner) and 89% healing in half the time (28 days) using 3/4 of the dose. Stated differently, PPSBT required 28 days and 84 grams of sucralfate to achieve 89% complete healing, while 224 grams of bio-inert gastric-acid polymerized sucralfate requires twice the time (56 days vs 28 days) to achieve 68% complete healing.

Conclusion

Pre-polymerized sucralfate barrier therapy was observed to be safe and effective in patients with symptomatic erosive GERD in a randomized double-blind placebo controlled trial. Its outsized treatment effect was likely related to the enhanced surface concentration of sucralfate that PPSBT achieves within the mucin gel overlying the gastroesophageal mucosa. The treatment effects observed in this and other randomized controlled trials of PPSBT [5,6,7] where unanticipated, though in hindsight and in view of the early basic science work on sucralfate [38, 39, 45], it was not entirely unforeseen. Should the PPSBT outcomes observed here and reported elsewhere, be repeated and confirmed, then a future of effective mucosal barrier therapies involving sucralfate would indeed be a 180 degree return to a past for the future. At the very least an alternative approach to symptomatic reflux disease may be at hand, an approach whose efficacy is associated with rapid healing [5,6], significant symptom control and based on denying acid, bile and proteases physical access to esophageal mucosa.

Summary Box

What is already known about this subject

a. Acid irritation is believed to be the sole concern for managing erosive GERD

b. Erosive GERD is best managed by proton pump inhibitors

c. Sucralfate has no role in the therapeutic management of erosive GERD

What are the new findings

a. Acid, bile acids and proteases are co-equal irritants for erosive GERD

b. Proton pump inhibitors do not address bile acids and proteases

c. Standard sucralfate is too weak to address acid, bile acids and proteases

d. FDA recognized pre-polymerized sucralfate barrier therapy effectively excludes acid, bile acids and proteases from esophageal mucosa in erosive GERD

Acknowledgement

Contracted trial director: Professor AK Azad Khan delegated responsibilities.

Contracted lead coordinator: Dr. Mian Mashed Ahmad lead coordinator responsible for organizing patient recruitment, management of endoscopies and scoring patient outcomes.

Contracted contributing investigators: Dr. MA Masud, Dr. Swapan Chandra Dhar, Dr. Md. Habibur Rahman, Dr. Dewan Saifuddin Ahmad, Dr. Hafeza Aftab, Dr. Hasan Masud, Dr. Naima Haque, Dr. Anisur Rahman, Dr. Mahmud Hasan. Each were responsible for patient assessment and test drug distribution.

Medical institutions: Department of Gastrointestinal & Liver Diseases, Dhaka Medical College Hospital (DMCH), Dhaka, Bangladesh; Department of Gastroenterology, Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujib Medical University (BSMMU), Dhaka, Bangladesh; Department of Gastrointestinal, Hepatobiliary and Pancreatic Disorders (GHPD) and Research Division, Bangladesh Institute of Research & Rehabilitation in Diabetes, Endocrine and Metabolic Disorders (BIRDEM), Dhaka, Bangladesh.

Trial Concept, Methodology, Data curation, literature research, formal analysis, writing, editing manuscript: RW McCullough MD.

Conflict of Interest

Author is employed by company who owns a technology that pre-polymerizes sucralfate. The company did not have any role in the execution of the study or interpretation of data. The terms of financial support excluded funder’s participation in data curation or study conclusions.

References

- Ishimori A (1971) Mechanism of the Antipeptic Action of Anionic Carbohydrate and Its Clinical Application for the Treatment of Peptic Ulcer. Tohoku J Exp Med 103: 141-157.

- (1982) US Food and Drug Administration. Carafate (Sucralfate).

- (1991) US Food and Drug Administration. Carafate (Sucralfate)Suspension.

- Oshea S (2019) Office of Combination Products. Request for Designation Sucralfate HCl Topical Paste.

- McCullough RW (2014) Mucosa-Centric Clinical Effects of High Potency Sucralfate: 28 Day 83% Resolution of Undifferentiated Dyspepsia, 28 Day 83% Reversal of Sign & Symptoms of Co-Morbid IBS and 1 Week 80% Healing of GERD. Gastroenterol 146(5, Suppl 1): S-263.

- McCullough RW (2020) Randomized Placebo-controlled Trial: Mucosal protection in the treatment of Non-erosive Reflux Disease (NERD) - efficacy of Esolgafate, a pre-polymerized cross-linked sucralfate medical device: Barrier therapy alone seems effective for NERD. Digestive Medicine Research.

- McCullough RW (2020) Randomized Controlled Trial of 7 Day Comparative Effectiveness in Heartburn Relief and Endoscopic Healing of Erosive GERD using Omeprazole, Ranitidine, Antacids and Esolgafate, a Pre-Polymerized Sucralfate Barrier Therapy Medical Device: Relief by Healing seems better than Relief by Acid control. The Academic Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

- Caviglia R, Ribolsi M, Maggiano N, Gabbrielli AM, Emerenziani S, et al. (2005) Dilated intercellular spaces of esophageal epithelium in non-erosive reflux disease patient s with physiological esophageal acid exposure. Am J Gastroenterol 100: 543-548.

- Kandulski A, Jechorek D, Caro C, Weigt J, Wex T, et al. (2013) Histomorphological differentiation of non-erosive reflux disease and functional heartburn in patients with PPI-refactory heartburn. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 38: 643-651.

- Woodland P, Al-Zinaty M, Yazaki E, Sifrim D (2013) In vivo evaluation of acid-induced changes in oesphageal mucosa integrity and sensitivity in non-erosive reflux disease. Gut 62: 1256-1261.

- Farre R (2013) Pathophysiology of gastro-esphageal reflux disease: a role for mucosa integrity. Neurogastroenterol Motil 25: 783-799.

- Weijenborg PW, Smout AJ, Verseijden C, van Veen HA, Verheij J, et al. (2014) Hypersensitivity to acid is associated with impaired esophageal mucosal integrity in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease with and without espohagitis. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 307: G323-G329.

- Yamasaki T, Fass R (2017) Reflux Hypersitivity: a new functional esophageal disorder. J Neurogastroenterol Motil 23(4): 495-503.

- Kanazawa Y, Isomoto H, Wen CY, Wang AP, Saenko V, et al. (2003) Impact of endoscopically minimal involvement on IL-8 mRNA expression in esophageal mucosa of patients with non-erosive reflux disease. World J Gastroenterol 9(12): 2801-2804.

- Fitzgerald RC, Onwuegbusi BA, Bajaj-Elliott M, Saeed IT, Burnham WR, et al. (2020) Diversity in the oesophageal phenotypic response to gastro-oesophageal reflux: immunological determinants. Gut 50: 451-459.

- Yu Y, Ding X, Wang Q, Xie L, Hu W, et al. (2011) Alterations of mast cells in the esophageal mucosa of the patients with non-erosive reflux disease. Gastroenterol Res 4(2): 70-75.

- Harnett KM, Rieder F, Behar J, Biancani P (2010) Viewpoints on acid-induce inflammatory mediators in esophageal mucosa. J Neurogastroenterol Motil 16(4): 374-388.

- Isomoto H, Wang A, Mizuta Y, Akazawa Y, Ohba K, et al. (2003) Elevated levels of chemokines in esophageal mucosa of patients with reflux esophagitis. Am J Gastroenterol 98: 551-556.

- Souza RF, Huo X, Mittal V, Schuler CM, Carmack SW, et al. (2009) Gastroesophageal reflux might cause esophagitis through a cytokine-mediated mechanism rather than caustic acid injury. Gastroenterol 137(5): 1776-1784.

- Farre R, van Malenstein H, De Vos R (2008) Short exposure of oesophageal mucosa to bile acids, both in acidic and weakly acidic conditions, can impair mucosal integrity and provoke dilated intercellular spaces. Gut 57: 1366-1374.

- Gotley DC, Morgan AP, Ball D, Owen RW, Cooper MJ, et al. (1991) Composition of gastro-oesophagel refluxate. Gut 32: 1093-1099.

- Hofmann AF, Mysels KJ (1992) Bile solubility and precipitation in vitro and in vivo: the role of conjugation, pH, and Ca2+ ions. J Lipid Res 33(5): 617-626.

- Nehra D, Howell P, Williams CP, Pye JK, Beynon J (1999) Toxic bile acids in gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: influence of gastric acidity. Gut 44: 598-602.

- Hershcovici T, Jha LK, Cui H, Powers J, Fass R (2011) Night-time intra-oesophageal bile and acid: a comparison between gastro-esophageal reflux disease patients who failed and those who were treated successfully with a proton pump inhibitor. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 33(7): 837-844.

- Ghatak S, Reveiller M, Toia L, Ivanov AI, Zhou Z, et al. (2016) Bile salts at low pH cause dilation of intercellular spaces in in vitro stratified primary esophageal cells, possibly by modulating Wnt signaling. J Gastrointest Surg 20: 500-509.

- Chen X, Oshima T, Shan J, Fukui H, Watari J, et al. (2012) Bile salts disrupt human esophageal squamous epithelial barrier function by modulating tight junction proteins. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 303: G199-G208.

- Li WT, Luo QQ, Wang B, Chen X, Yan XJ, et al. (2019) Bile acids induce visceral hypersensitivity via mucosal mast cell-t0-nociceptor signaling that involves the farnesoid X receptor/nerve growth factor/transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 axis. FASEB J 33(2): 2435-2450.

- Nagashima R (1981) Development and characteristics of sucralfate. J Clin Gastroenterol 3(Suppl2): 103-110.

- Mathews DR, Dahl NG (1995) Safety of sucralfate. In Sucralfate: From Basic Science to the Bedside. Daniel Hollander and GNJ Tytgat (eds.), New York. Plenum Press 21: 215-223.

- Katz PO, Gerson LB, Vela MF (2013) Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol 108: 308-328.

- Huerta-Iga F, Bielsa-Fernández MV, Remes-Troche JM, Valdovinos-Díaz MA, Tamayo-de la Cuesta JL, et al. (2016) Diagnosis and treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease: recommendations of the Asociación Mexicana de Gastroenterologí Revista de Gastroenterol Mex 81(4): 208-222.

- Fock KM, Talley N, Goh KL, Sugano K, Katelaris P, et al. (2008) Asia-Pacific concensus on the management of gastroesophageal reflux disease: update. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 23: 8-22.

- Armstrong D, Marshall JK, Chiba N, Enns R, Fallone CA, et al. (2005) Canadian Consensus Conference on the management of gastroesophageal reflux disease in adults –update 2004. Can J Gastroenterol 19: 15-35.

- Holland D, Tytgat GNJ (1995) Sucralfate: From Basic Science to the Bedside. Daniel Hollander and GNJ Tytgat (eds.), Plenum Press, New York.

- Morris GP (1995) Binding of sucralfate to mucosal surface. In Sucralfate: from basic science to the bedside. Daniel Hollander and GNJ Tygat (eds.), Plenum Press, New York.

- Cohen MM, Bowdler R, Gervais P, Morris GP, Wang HR (1989) Sucralfate protection of human gastric mucosa against acute ethanol injury. Gastroenterol 96: 292-298.

- Tasman-Jones C, Morrison G, Thomsen L, van Derwee M (1989) Sucralfate interactions with gastric mucus. Am J Med 86(suppl6A): 5-9.

- Slomiany BL, Murty VL, Piotrowski J, Slomiany (1989) Effect of antiulcer agents on the physiochemical properties of gastric mucus. Symp Soc Exp Biol 43: 179-191.

- Slomiany BL, Laszewicz W, Murty VL, Kosmala M, Slomiany A (1985) Effect of sucralfate on the viscosity and retardation of hydrogen ion diffusion by gastric mucus glycoprotein. Comp Biochem Physiol C 82(2): 311-314.

- Slomiany BL, Liu J, Slomiany A (1992) Modulation of gastric mucosal calcium channel activity by sucralfate. Biochem Int 28(6): 1125-1134.

- Caspary WF (1995) Binding of bile salts by sucralfate. In Sucralfate: from basic science to the bedside. Daniel Hollander and GNJ Tygat (eds.), Plenum Press, New York.

- Schweitzer EJ, Bass BL, Johnson LF, Harmon JW (1985) Siucralfate prevents experimental peptic esophagitis in rabbits. Gastroenterol 88: 611-619.

- Louw JA, Young GO, Winter TA, Marks IN (1995) Sucralfate and Helicobacter Pylori. In Sucralfate: from basic science to the bedside. Daniel Hollander and GNJ Tygat (eds.), Plenum Press, New York.

- Slomiany BL, Piotrowski J, Slomiany A (1992) Effect of sucralfate on the degradation of human gastric mucus by helicobacter pylori protease and lipases. Am J Gastroenterol 87(5): 595-599.

- Tarnawski A, Hollander D, Stachura J, Mach T, Bogdal J (1987) Effect of sucralfate on the normal human gastric mucosa. Endoscopic, histologic, and ultrastructural assessment. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl 127: 111-123.

- Tarnawski A, Hollander D, Krause WJ, Zipser RD, Stachura J, et al. (1986) Does sucralfate affect the normal gastric mucosa? Histologic, ultrastructural and functional assessment in the rat. Gastroenterol 90(4): 893-905.

- Benson H, Friedman R (1996) Harnessing the power of the placebo effect and renaming it “remembered wellness”. Annu Rev Med 47: 193-199.

- Medical Research Council of Bangladesh. Clinical Trial Registry 2004-2005.

- Fraser AG, Butchart EG, Szymański P, Caiani EG, Crosby S, et al. (2018) The need for transparency of clinical evidence for medical devices in Europe. Lancet 392: 521-530.

- (2015) International Medical Device Regulators Forum. ISO 14155:2011. Clinical investigation of medical devices for human subjects-Good clinical practice.

- Kashimura K, Ozawa K (1999) Sucralfate Preparations.

- Shiovitz TM, Bain EE, McCann DJ, Skolnick P, Laughren T, et al. (2016) Mitigating the Effects of Nonadherence in Clinical Trials. J Clin Pharmacol 56(9): 1151-1164.

- Hetzel DJ, Dent J, Reed WD, Narielvala FM, Mackinnon M, et al. (1988) Healing and relapse of severe peptic esophagitis after treatment with omeprazole. Gastroenterology 95: 903-912.

- Khan M, Santana J, Donnellan C, Preston C, Moayyedi P (2007) Medical treatments in the short term management of reflux oesophagitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2: CD003244.

- Ishimori A (1995) History of the Development of Sucralfate. In Sucralfate: From Basic Science to the Bedside, Daniel Hollander and GNJ Tytgat (eds.), Plenum Press, New York.

- (2019) Sucralfate.

- (2019) Association of the European Self-Care Industry (AESGP). Sucralfate Database.

- Kise Y, Aihara R, Chino O, Yamamoto S, Hara T, et al. (2006) Sucralfate-formed esophageal bezoar detected following sudden vomiting. Endoscopy 38(Suppl2): E70.

- Vermeijden JR, Tytgat GN, Schotborgh RH, Dekker W, vd Boomgaard DM, et al. (1992) Combination therapy of sucralfate and ranitidine, compared with sucralfate monotherapy, in patients with peptic reflux esophagitis. Scand J Gastroenterol 27(2): 81‐84.

-

Ricky Wayne McCullough. 28 Day Randomized Double-Blind Placebo Controlled Trial using Pre-Polymerized Cross-Linked Sucralfate Barrier (Esolgafate) for Erosive GERD. Acad J Gastroenterol & Hepatol. 2(1): 2020. AJGH.MS.ID.000528.

-

Polymerized sucralfate, Barrier therapy, Erosive GERD, Randomized controlled trial, Heartburn, Hypersensitivity syndrome, Epithelium, Gastric acid, Gastroesophageal mucosa, Helicobacter pylori

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.