Case Report

Case Report

Eosinophilia and Neutrophilia Associated with Anti- PD-1 use in Metastatic Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer – A Case Report

Yasir Khan* and Christopher Lomma

Department of Medical Oncology, Fiona Stanley Hospital, Western Australia, Australia

Yasir Khan, Department of Medical Oncology, Fiona Stanley Hospital, Australia.

Received Date: January 23, 2021; Published Date: January 29, 2021

Abstract

The use of immunotherapy has dramatically changed the way many cancers are treated with several studies having looked at the relationship between eosinophils and immunotherapy. This case study reports nivolumab induced eosinophilia and neutrophilia with no other systemic adverse effects in a patient with metastatic non-small cell lung cancer. A 61-year-old woman with Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status 1 was diagnosed with metastatic non-small cell lung cancer without any driver mutations and was commenced on nivolumab after progressing on platinum doublet therapy. She had mild eosinophilia and neutrophilia at baseline in the context of a lower respiratory tract infection which became more pronounced with the introduction of nivolumab. Nivolumab was ceased at week-26 due to significant eosinophilia and reached peak levels at week-35. She developed postural hypotension during the course of her disease and prednisolone was commenced to treat possible adrenal insufficiency from metastasis. The introduction of steroids led to the improvement in eosinophilia and neutrophilia. She had stable disease for 8 months after commencement of immunotherapy before progression of disease leading to clinical deterioration and death. Asymptomatic eosinophilia and neutrophilia is an extremely rare toxicity of immune checkpoint inhibitors. Its significance as prognostic and predictive marker needs to be researched further.

Keywords: Immunotherapy induced eosinophilia; Neutrophilia; Nivolumab.

Introduction

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI) targeting PD-1, PD-L1 and CTLA-4 are routinely used in clinical practice in multiple tumour types. These drugs are very effective especially for solid organ malignancies with high mutational load but carry a wide spectrum of toxicities driven by over stimulation of immune system. Immunerelated adverse events (irAEs) range from low grade toxicities to severe toxicities which can potentially be life threatening in some cases. Among some of the uncommon side effects, immunotherapy induced eosinophilia is a rare toxicity with only a few documented cases and mostly associated with eosinophilia related systemic manifestations or with additional toxicities. There are well established guidelines for treating common irAEs but little is known about the optimal management of rarer toxicities like asymptomatic eosinophilia. This case study reports nivolumab induced eosinophilia and neutrophilia with no other systemic adverse events in a patient with metastatic non-small cell lung cancer.

Case Report

A 61-year-old woman was admitted with the diagnosis of lower respiratory tract infection with investigations leading to a diagnosis of stage IV adenocarcinoma of the lung without targetable mutations. She had a left lung mass, hilar nodes enlargement, malignant ipsilateral pleural effusion and liver metastases. PDL1 status was not obtained as there were no standard treatments based on PD-L1 levels at that time. She was a smoker and had Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status 1.

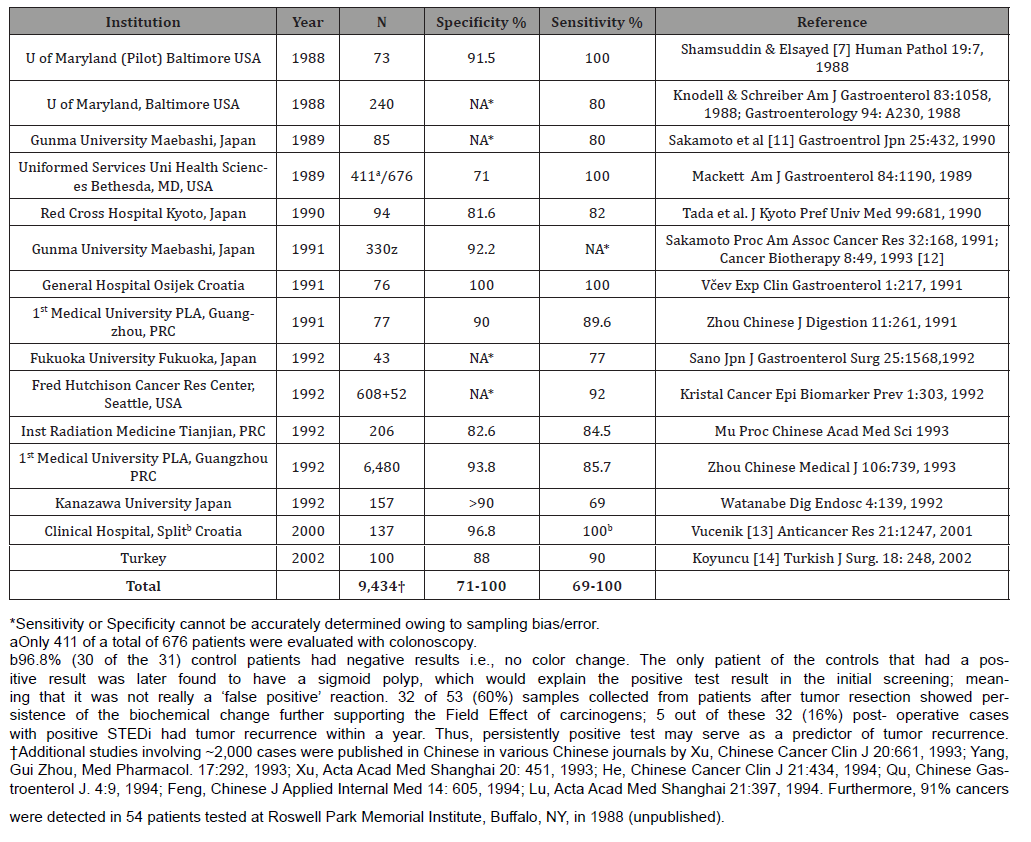

Due to prescribing restrictions applicable at that time, she was initially commenced on carboplatin and gemcitabine chemotherapy before progression of disease. Second line pemetrexed was given but it failed to provide any clinical benefit. She was then commenced on nivolumab monotherapy. Initial interval scan suggested worsening of disease, however given there was no clinical deterioration, she was given the benefit of doubt and nivolumab was continued on the assumption of pseudo progression. Her baseline neutrophils and eosinophils count were mildly elevated (Table 1). Of note this was in the setting of lower respiratory tract infection. The elevated eosinophil counts were persistent but still mild at the commencement of nivolumab. Both neutrophilia and eosinophilia were more pronounced at 14 weeks post-nivolumab and reached peak levels at 35 weeks (Figure 1) (Table 1).

Table 1:Serial full blood counts (FBC).

Nivolumab was stopped after 13 cycles due to worsening of eosinophilia and neutrophilia in the context of stable disease on imaging. Patient did not have any other systemic features at the time when nivolumab was stopped. Possible differential diagnosis at that stage included paraneoplastic phenomenon, immune mediated toxicity, and myeloproliferative disorder. She started to deteriorate clinically with recurrent falls. Adrenal insufficiency was considered to be the most likely diagnosis based on the clinical features of postural hypotension, hyponatremia, hyperkalemia and finding of left adrenal metastasis on repeat imaging. This diagnosis was further confirmed by inadequate response of adrenal glands to short synacthen test. She was commenced on prednisolone to correct adrenal insufficiency which also led to the improvement in neutrophilia and eosinophilia. Eventually disease progression was recorded soon afterwards along with clinical deterioration predominantly from progression in the lungs causing respiratory failure and death. She had 14 months of survival since diagnosis of the cancer. Progression free survival on immunotherapy was 8 months with stable disease being the best response.

Discussion

A well-known cause of hyper eosinophilia is the DRESS (drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms) syndrome. Common features of DRESS include blood eosinophilia, fever, skin changes, facial oedema, visceral involvement, and atypical lymphocytes [1]. DRESS has been reported to be associated with immunotherapy. Mirza et al presented a case of patient who developed DRESS after combination ipilimumab and nivolumab for melanoma and successfully treated with steroids [2]. Voskens et al also presented a case of DRESS syndrome following ipilimumab for melanoma which responded to steroids [3]. Furthermore, there have been other case reports documenting relationship between immunotherapy and eosinophilia with uncommon systemic manifestations. Khoja et al. presented a case of a patient who developed eosinophilic fasciitis and cerebral vasculitis one month after completing an 18-month course of pembrolizumab for metastatic melanoma [4]. Okano et al presented a case of a patient with hypophysitis with associated eosinophilia following nivolumab for metastatic lung cancer [5]. To our knowledge, there are only two case series published in literature in regard to nivolumab induced eosinophilia, however a majority of those patients also experienced other irAEs of various grades [6,7]. In addition to this, there have been five published case reports of nivolumab induced eosinophilia to date [2,8-11]. Our report documents a case with isolated hematological abnormalities including eosinophilia and neutrophilia without systemic features in a patient treated with nivolumab for metastatic non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) which is a rare toxicity of anti-PD-1 antibodies.

The role of eosinophils in tissue homeostasis is not fully understood. Nevertheless, certain conditions have a well-known association with eosinophilia such as allergic diseases, infectious diseases (especially parasitic infections), autoimmune diseases (especially adrenal insufficiency) and haematological disorders. Eosinophilia has also been described as a paraneoplastic phenomenon of many solid organ malignancies and is most associated with an advanced stage and poor prognosis [12]. Eosinophils can also play a role in pathogenesis through depositing granules which can have both direct toxic effects and recruit as well as activate other inflammatory cells [13]. A hypereosinophilic syndrome (HES) in which there are symptoms from a high eosinophil count in blood or tissue has been described with the underlying cause often never found despite extensive investigation [12,13]. There are various mechanisms reported in the literature to explain pathophysiology of eosinophilia. Immune proteins and cytokines like interleukin-3 (IL-3) and interleukin-5 (IL-5) have been associated to play a role in elevated eosinophil counts [14,15]. Our patient also had neutrophilia in addition to eosinophilia. Neutrophilia is induced by granulocyte macrophage colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF). Interaction and interplay of immune proteins like GM-CSF, IL-3 and IL-5 leads to activation of multiple cell lines. The role of eosinophils in tumour microenvironment is not well known and may possess anti-tumour effects in some cases while promoting tumorigenesis in others [16]. Its value as prognostic and predictor factor is also unclear. Eosinophilia at diagnosis of the cancer has been linked with poor prognosis in some advanced malignancies [17,18]. On the other hand, some pre-clinical studies indicate immunotherapy induced eosinophilia may be a predictor of response to treatment. In our case, when immunotherapy was stopped after 13 cycles the best response achieved with immunotherapy was stable disease only. As eosinophilia pre-dated the start of immunotherapy, at least in our case, it does not seem to be associated with treatment response or effectiveness.

Conclusion

Asymptomatic eosinophilia and neutrophilia is an extremely rare toxicity of ICI. Development of eosinophilia in the setting of immunotherapy use needs to be studied further to delineate its role as both prognostic and predictive marker.

Acknowledgement

None.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest.

References

- Skowron F, Bensaid B, Balme B, Depaepe L, Kanitakis J, et al. (2015) Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS): clinicopathological study of 45 cases. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 29(11): 2199-2205.

- Mirza S, Ebone’Hill, Steven P Ludlow, Sowmya Nanjappa (2017) Checkpoint inhibitor-associated drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptom syndrome. Melanoma Res 27(3): 271-273.

- Voskens CJ, Simone M Goldinger, Carmen Loquai, Caroline Robert, Katharina C Kaehler, et al. (2013) The price of tumour control: an analysis of rare side effects of anti-CTLA-4 therapy in metastatic melanoma from the ipilimumab network. PLoS ONE. 8(1): e53745.

- Khoja L, Catherine M, Mary Anne C, Leslie MacMillan, Marcus OB, et al. (2016) Eosinophilic fasciitis and acute encephalopathy toxicity from pembrolizumab treatment of a patient with metastatic melanoma. Cancer Immunol Res 4(3): 175-178.

- Okano Y, Tetsurou Satoh, Kazuhiko Horiguchi, Minoru Toyoda, Aya Osaki, et al. (2016) Nivolumab-induced hypophysitis in a patient with advanced malignant melanoma. Endocrine Journal 63(10): 905-912.

- Bernard Tessier A, Priscilla Jeanville, Christine Mateus, Olivier Lambotte, Maxime, A et al. (2017) Immune-related eosinophilia induced by anti-programmed death 1 or death-ligand 1 antibodies. European Journal of Cancer 81:135-137.

- Scanvion Q, Béné J, Gautier S, Chenaf C, Etienne N, et al. (2020) Moderate-to-severe eosinophilia induced by treatment with immune checkpoint inhibitors: 37 cases from a national reference center for hypereosinophilic syndromes and the French pharmacovigilance database. Oncoimmunology 9(1):1722022.

- Y Lou, J A Marin Acevedo, P Vishnu, Soyano A, Zhang Y, et al. (2019) Hypereosinophilia in a patient with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer treated with antiprogrammed cell death 1 (anti-PD-1) therapy. Immunotherapy 11(7): 577–584.

- R Ariyasu, A Horiike, T Yoshizawa (2017) Adrenal insufficiency related to anti-programmed death-1 therapy. Anticancer Research 37(8): 4229–4232.

- H Osawa, S Okauchi, S Taguchi, K Kagohasi, H Satoh (2018) Immuno-checkpoint inhibitor associated hyper-eosinophilia and tumor shrinkage. Tuberkuloz ve Toraks 66(1): 80–83.

- Singh N, Lubana SS, Constantinou G, Leaf AN (2020) Immunocheckpoint Inhibitor- (Nivolumab-) Associated Hypereosinophilia in Non-Small-Cell Lung Carcinoma. Mayordomo JI. Case Rep Oncol Med 2020:7492634.

- Montgomery ND, Cherie H Dunphy, Micah Mooberry, Andrew Laramore, Matthew C Foster, et al. (2013) Diagnostic Complexities of Eosinophilia. Arch Pathol Lab Med 137(2): 259-269.

- Kloin AD (2015) Eosinophilia: a pragmatic approach to diagnosis and treatment. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program 2015(1): 92-97.

- Cormier SA, Taranova AG, Bedient C, Nancy A Lee, James J Lee, et al. (2006) Pivotal advance: eosinophil infiltration of solid tumors is an early and persistent inflammatory host response. J Leukoc Biol 79(6):1131–1139.

- Rosenberg HF, Dyer KD, Foster PS (2013) Eosinophils: changing perspectives in health and disease. Nat Rev Immunol 13(1): 9–22.

- Tepper RI, Coffman RL, Leder P (1992) An eosinophil-dependent mechanism for the antitumor effect of interleukin-4. Science 257(5069):548–551.

- El Osta H, El Haddad P, Nabbout N (2008) Lung carcinoma associated with excessive eosinophilia. J Clin Oncol 26(20):3456–3457.

- Teoh SC, Siow WY, Tan HT (2000) Severe eosinophilia in disseminated gastric carcinoma. Singapore Med J 41(5):232-234.

-

Yasir Khan, Christopher Lomma. Eosinophilia and Neutrophilia Associated with Anti-PD-1 use in Metastatic Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer – A Case Report. Adv Can Res & Clinical Imag. 3(1): 2021. ACRCI.MS.ID.000555.

-

Basal cell carcinoma, Horizontally orientation, Tumor margins, Probable radiotherapy, Lymph node dissection

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.